“The President is Very Acutely Ill”

Harry S. Truman’s Illness of July 1952

Fall 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2

By Samuel W. Rushay, Jr.

"The President is very acutely ill. . . ."

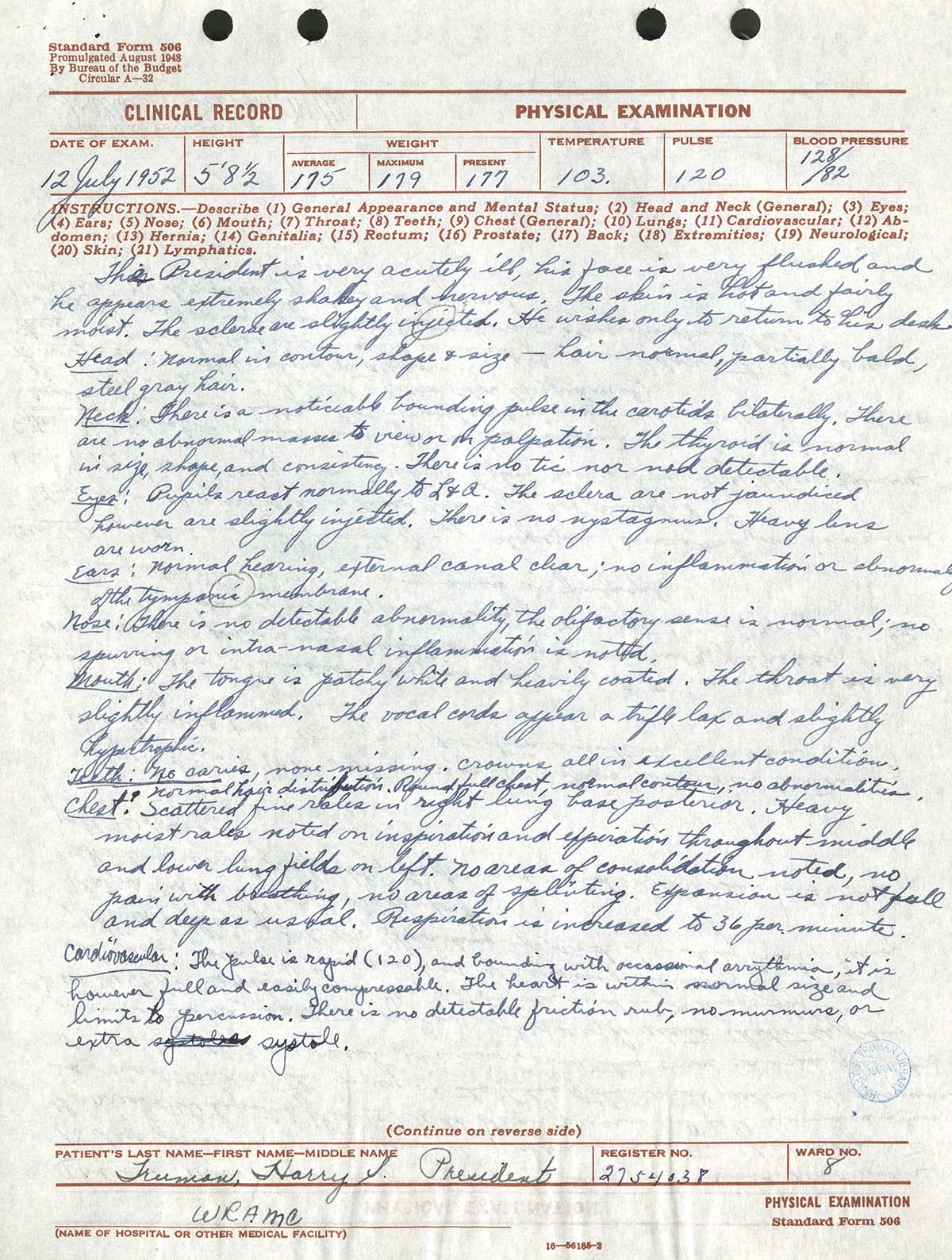

So began a medical report of July 12, 1952, by Dr. Wallace Graham, personal physician to President Harry S. Truman. The 33rd President was 68 years old and nearing the end of his second term in the Oval Office. Vigorous and hardworking, Truman frequently worked 18-hour days and had a tendency, according to his daughter, Margaret, to "ignore his illnesses until they either went away or they floored him."

Harry Truman was a healthy President who was very rarely kept away from his office due to sickness. That changed in the summer of 1952, when he was hospitalized with a streptococcus infection. What is remarkable about that episode is how little the White House revealed about Truman's illness and how accepting the press was with White House responses to its numerous questions about the President's health.

In the summer of 1952, Truman was busy with matters concerning a nationwide steel strike, Korean War negotiations, and the upcoming presidential election. In March, he had announced that he was not running for a third presidential term, and in the spring and summer of 1952, he was heavily involved in discussions concerning who should receive the Democratic Party's nomination.

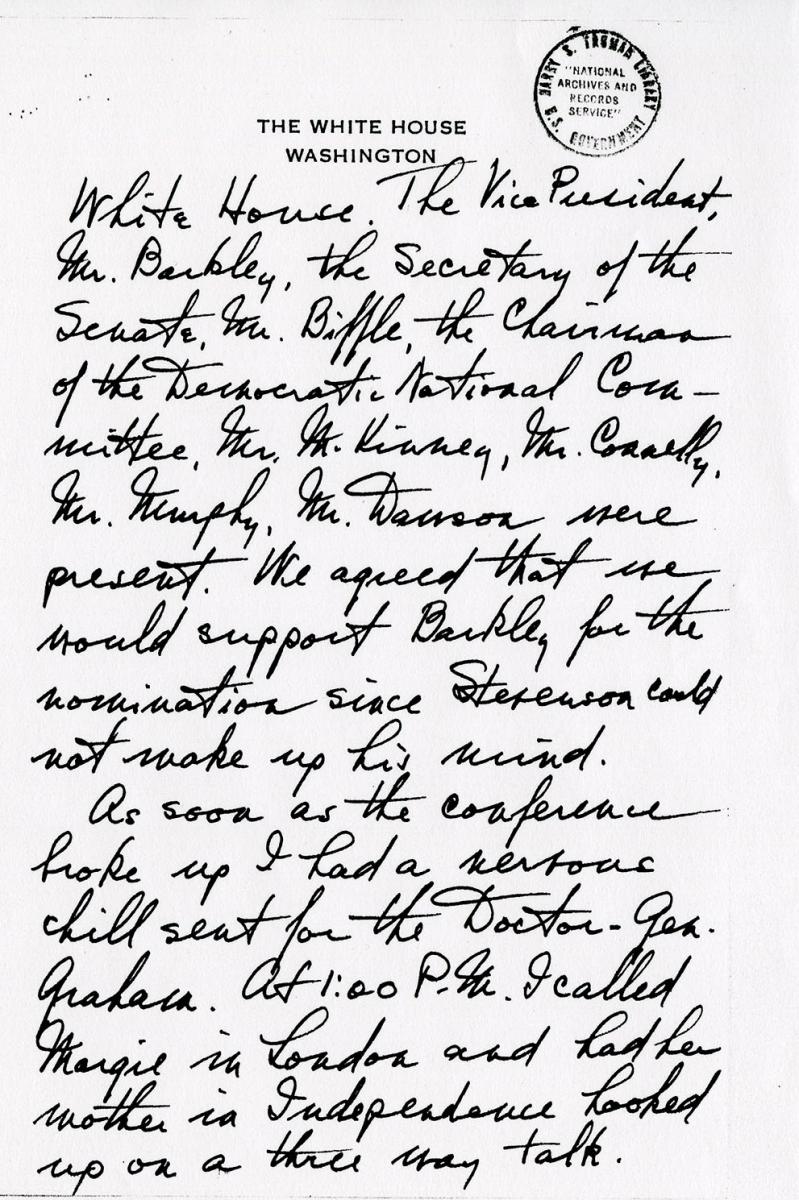

After a Sunday, July 13, meeting in which Truman and his political inner circle agreed to support Vice President Alben Barkley for the nomination (which ultimately went to Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois), the President experienced a "nervous chill" and sent for his doctor, Gen. Wallace Graham. He then called his daughter, Margaret, in London and his wife, Bess, in Independence, speaking with them on a three-way connection. Truman's body temperature reached 103.6 degrees that day, and on the following day, July 14, he was taken to Walter Reed Army Hospital for tests and observation. At Walter Reed, the President reported being "stuck . . . full of holes," being given pills, and having a lot of blood taken for examination. Bess then arrived and "took charge" of his care. By his own account, the President mostly slept for 48 hours. And that is all that we knew about the story for almost 60 years.

According to a medical report that the Truman Library opened in 2010, there was much more to this story. Truman's illness began on Friday, July 11, with a feeling of fatigue and "general malaise." A sore throat, radiating abdominal pain, and a burning feeling during urination followed.

By Sunday, July 13, the President "felt extremely nervous and had a shaking chill." His temperature was indeed 103 degrees. His pain was relieved when standing, sitting, or leaning forward, and it increased when he was lying down. His face was "very flushed and he appears extremely shaky and nervous. The skin is hot and fairly moist." His pulse was rapid, 120, and his blood pressure was 128/82, which is normal. Truman experienced no pain while breathing, but "heavy moist rales," or abnormal sounds, could be heard. All that being said, Dr. Graham's patient still "wishes only to return to his desk."

Dr. Graham's medical report never suggested that President Truman's life was in danger. Nor was there evidence that the President was ever unable to perform his duties. Still, he was a sick man. A throat culture revealed he had three bacteria: Alpha Streptococcus (strep throat), Hemophilis influenza (flu), and Neisseria catarrhalis, which infects the respiratory tract and can cause bronchitis and pneumonia (neither of which were noted in Dr. Graham's medical report although he later referred to the President suffering "one bout of pneumonia that was quite striking").

It is unknown what types of drugs Dr. Graham prescribed for Truman, although penicillin and other antibiotics were listed in terms of sensitivities of the bacteria to those drugs. Before this illness, Dr. Graham had observed that "at certain times he would have considerable pulmonary congestion and it wasn't true asthma, but it was asthma-like congestion. He would breathe just a little more short."

In his unpublished memoir, Dr. Graham recalled his 1945 conversation with a Senate doctor who said he did not envy Graham because in his view, Truman's pulmonary blockage was so serious the new President might not survive his term.

In September of 1937, Truman spent a week and a half at the Army-Navy Hospital at Hot Springs, Arkansas. He was suffering from exhaustion, headaches, and nausea. A thorough checkup indicated that he was experiencing the effects of overwork and job-related stress, although there was nothing seriously wrong with him. Truman returned to the hospital at Hot Springs on a couple of occasions during his Senate career, to rest and undergo further examinations.

White House Press Corps Doesn't Get the Whole Story

The press knew none of this information. On Monday, July 14, Press Secretary Joseph Short revealed that Truman would stay in his quarters because he suffered from a "mild virus infection" and thought—he did not know for sure—that he had a "mild temperature." Asked if the President had a cold, Short replied, "Don't press me." Asked if he had the flu, Short said "[International News Service reporter Robert] Nixon is on the right track" (i.e., the President had a cold). He preferred that the press not reveal that the President was "up and down" or spent part of his time in bed sick. One reporter quipped, "Let's send him a bottle of blackberry brandy."

The following day, Short confirmed that the President had a "slight temperature" but could not (or chose not to) answer a question about whether the condition had been localized with no bronchial disturbance. He stuck to the "mild virus infection" description, never revealing (or, perhaps, knowing) the bacterial component of the President's illness.

The President remained sick in bed on July 14 and July 15, and he cancelled appointments on both days. On July 16, Short confirmed that the President had been taken to Walter Reed Hospital for a checkup. Truman had "shaved and dressed himself and went out in his car." His secretary, Rose Conway, was going to work with him at the hospital. The President had no fever, his temperature was normal, and he was very close to a complete recovery, according to the press secretary. Anthony Leviero of the New York Times reported that Short had declined a request by reporters for a filmed or recorded statement on the President's condition, saying "The whole thing will evaporate so quickly that it is not worth a special statement."

At Walter Reed, eight medical specialists examined the President, who ate and slept well, signed numerous bills, and thought about what he would say the upcoming Democratic National Convention, delivering his speech "to the bedpost." In the postscript to a letter accepting the resignation of William Hassett as secretary to the President, Truman quipped, "Mr. Hassett didn't get this one up. The 'Old Man' did it!" Still, the President's calendar showed he cancelled appointments between July 14 and July 18.

On July 17, Short did say that Truman's temperature could "go up just a teeny bit again today as it did yesterday," the fifth day in a row he had experienced a fever.

On July 18, a Friday and one week after the President's onset of symptoms, a reporter asked Short again if the White House planned to "put out any description or detail on the results of this physical checkup" of the President. Short responded, "I haven't gone into that with the doctor. Just don't know." That report was never issued to the public.

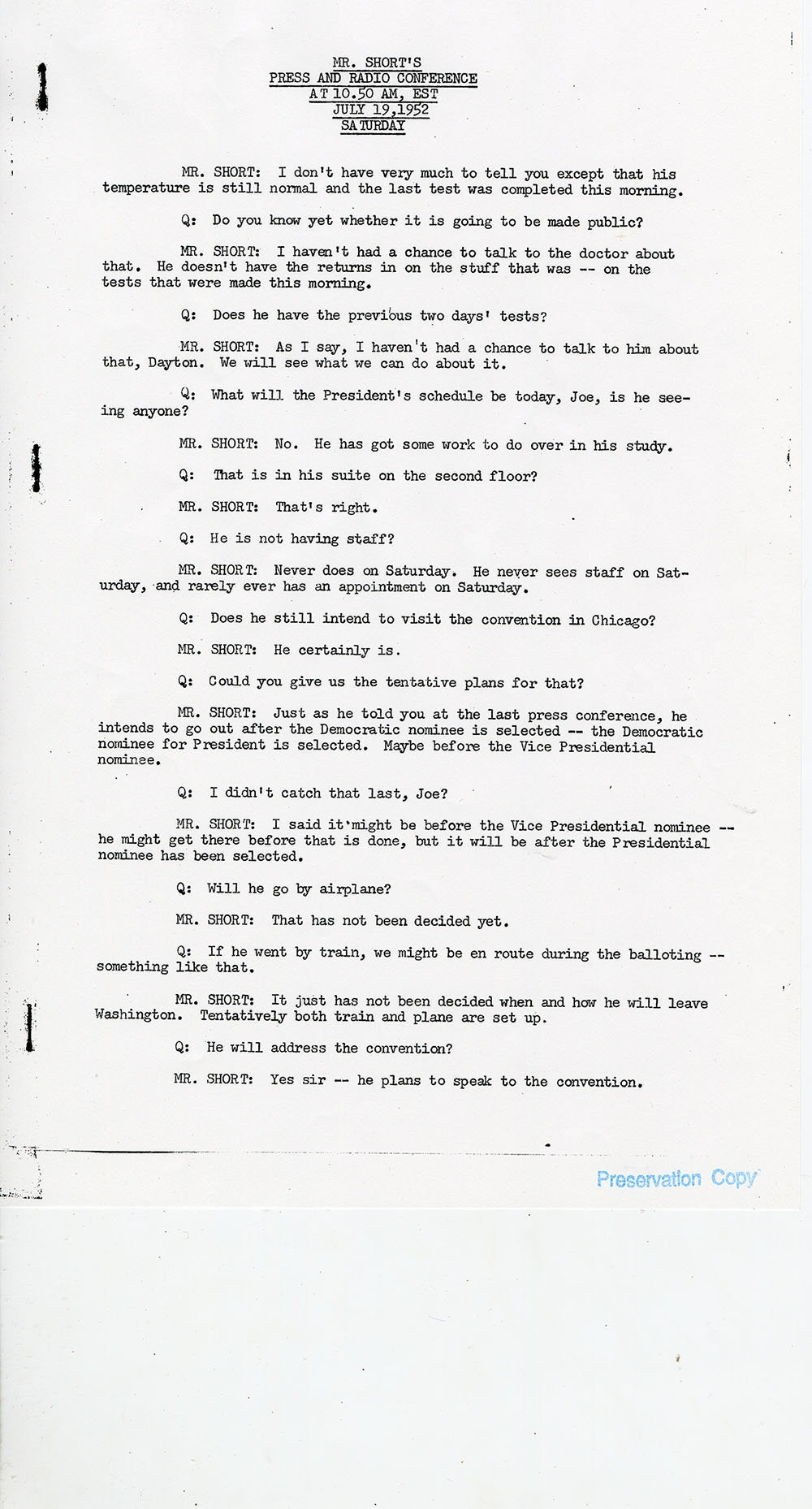

On Saturday, July 19, Truman returned to the White House from the hospital, where he had spent the previous five days. Reporters asked if Truman's illness would interfere with his plans to make a whistlestop tour to back up the Democratic presidential candidate. "Goodness no," replied Short. "You are talking about this little illness preventing a whistle-stop thing? Certainly not." That trip would not begin until well into the future any way, until around Labor Day.

The President received no visitors on Sunday, July 20.

By Monday, July 21, Truman was back at his desk for the first time since July 12 and was feeling "chipper." On July 26, he delivered an address at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago before going to Independence for a vacation.

Truman Recovers, But Public Never Knew of His Illness

President Truman made a full recovery from his bout with strep throat, the flu, and a pulmonary infection. Still, he had been sick for a week, and the American people had known very little about his illness. Some of what they did know was inaccurate and incomplete. The President's physician, Dr. Graham, freely admitted years later that he had withheld information about President Truman's health from the press.

There were no leaks to the press about the President's maladies in July 1952, an era before the advent of investigative journalism. It appears that the press corps took comments by Short and Dr. Graham at face value.

In ensuing years, Americans have grown accustomed to learning more about the lives and health of Presidents. It is debatable whether Americans deserved more information about Truman's illness during the summer of 1952. After all, there is no evidence that the President was ever incapacitated or rendered unable to perform his duties at any point.

Still, at age 68, Truman had already exceeded the life expectancy for an American male, which in 1952 was 66.6. Furthermore, only the advent of antibiotics rendered strep throat the mild illness that it is today. It had been a major cause of death in hospitals during World War II, and many Americans in 1952 would have recalled that famed Notre Dame football star George ("the Gipper") Gipp had died from a streptococcal throat infection just 30 years earlier, in 1920.

Unlike today, Americans might have been frightened to learn that their President had strep throat, a factor perhaps weighing in Dr. Graham's mind as he decided not to share the President's medical condition with the public.

If not life threatening, however, Truman's illness was considerably worse than the common cold. In the view of a physician who recently examined the President's available medical records, the President in July 1952 was "a very ill patient" who, in addition to strep throat, may have suffered from diverticulitis, pneumonia, and perhaps a gall bladder infection. Truman would have his gall bladder and appendix removed in 1954.

And in a sense, the severity of his ailments is beside the point if one accepts the notion that Presidents should make public their health information as part of their accountability to the American people.

Samuel W. Rushay, Jr., is supervisory archivist at the Truman Library and Museum, where he worked as an archivist from 1993 to 1997. From 1997 to 2007 he was an archivist and subject matter expert at the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. He holds a doctorate in U.S. history from Ohio University, where he wrote his dissertation, "The Farm Fair Dealer: Charles F. Brannan and American Liberalism" (2000), under the direction of Truman biographer Alonzo Hamby.

Note on Sources

The Harry S. Truman Library's manuscript collections include a small volume of papers and medical records related to President Truman's acute illness of July 1952. In 2010, the library opened for research the Papers of Wallace Graham, Truman's White House physician and personal physician until Truman's death in 1972. Dr. Graham's handwritten medical reports and various drafts of an unpublished memoir are located in the Graham Papers.

The oral history interview that Jerald Hill and William Stilley conducted with Dr. Graham contains some details about Truman's overall health, but almost nothing about his hospitalization in 1952. Dr. Graham's candid confession that he had withheld information about Truman's health from the press is found in Niel Johnson's oral history interview with Dr. Graham; transcript at www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/oral_his.htm#G.

In the President's Secretary's File (PSF), the Longhand Notes File of July 11, 1952, contains Truman's handwritten, diary-like entry concerning the onset of his illness. The PSF, Press Release File, contains Truman's letter of July 15 concerning Secretary Hassett's resignation. The President's daily calendar for the period July 14–20, 1952, which Appointments Secretary Matthew Connelly compiled, sheds little light on the nature of Truman's illness. Press Secretary Joseph Short provided remarkably vague and partial information and answers to questions posed by reporters who did not seem interested in asking tough questions concerning the nature of Truman's ailments. Transcripts of Short's press conferences are contained in the Papers of Joseph and Beth Campbell Short, Scrapbook File. Contemporaneous news accounts by reporters such as Anthony Leviero reveal little about why the President was hospitalized in 1952.

Margaret Truman's observation about her father's strenuous work habits is found in D. M. Giangreco and Kathryn Moore, eds., Dear Harry . . . Truman's Mailroom, 1945–1953: The Truman Administration Through Correspondence with "Everyday Americans" (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999), p. 9. The reference to Truman delivering his convention speech "to the bedpost" comes from David McCullough, Truman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), p. 902.

The author appreciates the assistance provided by Truman Library archivist Randy Sowell, who provided information about Truman's hospitalizations while he was in the Senate. The author is grateful to Dr. Roman Enriquez of North Kansas City Hospital, who examined the medical records and offered his analysis that Truman had been a "very ill patient." Dr. Enriquez was a resident physician at Trinity Lutheran Hospital in Kansas City at the same time that Dr. Graham practiced medicine there in the 1980s.