They Said It Couldn’t Sink

NARA Records Detail Losses, Investigation of Titanic’s Demise

Spring 2012, Vol. 44, No. 1

By Alison Gavin and Christopher Zarr

Perhaps no other maritime disaster stirs our collective memory more than the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912.

The centennial of this event brings to mind the myriad films, books, and electronic media the disaster engenders. The discovery of the ship at the bottom of the sea in the 1980s brought to view intriguing artifacts.

The National Archives holds Titanic-related "treasures" as well: Senate investigation records, documents pertaining to Titanic passengers from limited liability suits, and congressional resolutions. These records tell the stories of the survivors in their own words.

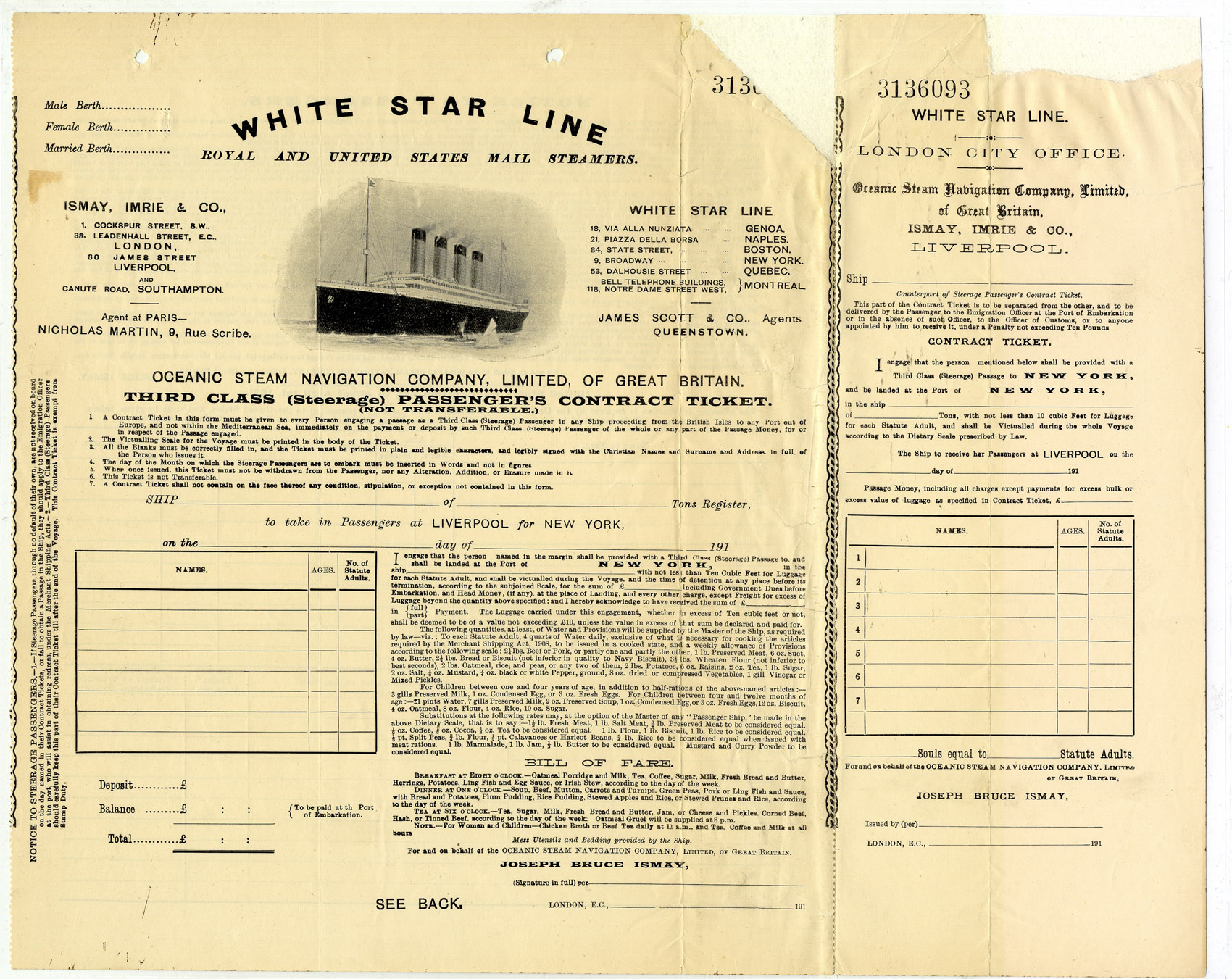

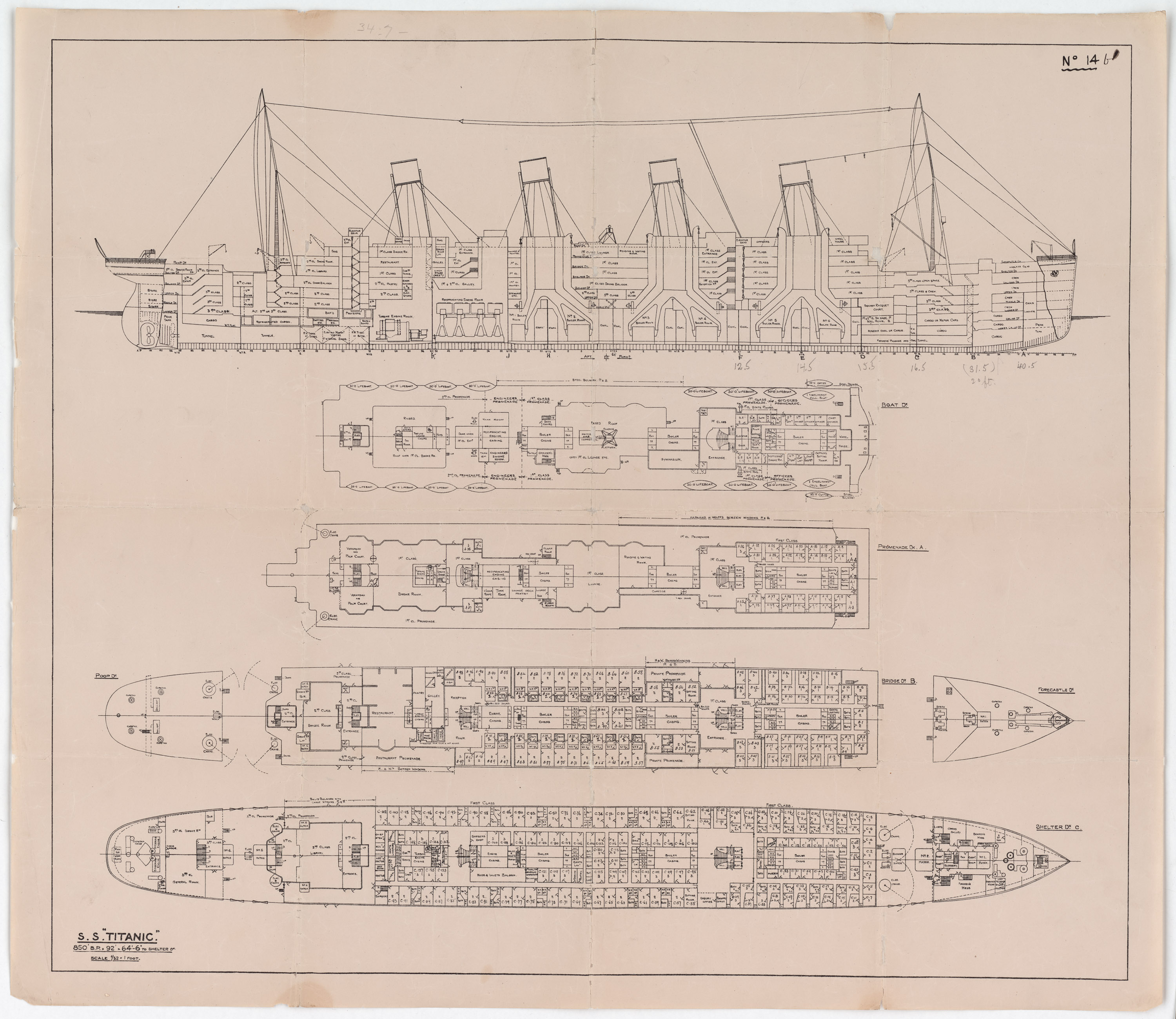

When Titanic set sail from Southampton, England, for New York City on April 10, 1912, no one, especially its builders, dreamed of its demise. The ship's owners, the White Star Line, boasted of the size and stamina of the largest passenger steamship built until that time. Yet the "ship that could never sink" sank less than three hours after the crew spotted an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on April 14. Of the 2,223 people aboard, 1,517 perished.

The lack of sufficient lifeboats was chief among the reasons cited for the enormous loss of life. While complying with international maritime regulations (Titanic carried more than the minimum number of lifeboats required), there were still not enough spaces for most passengers to escape the sinking ship.

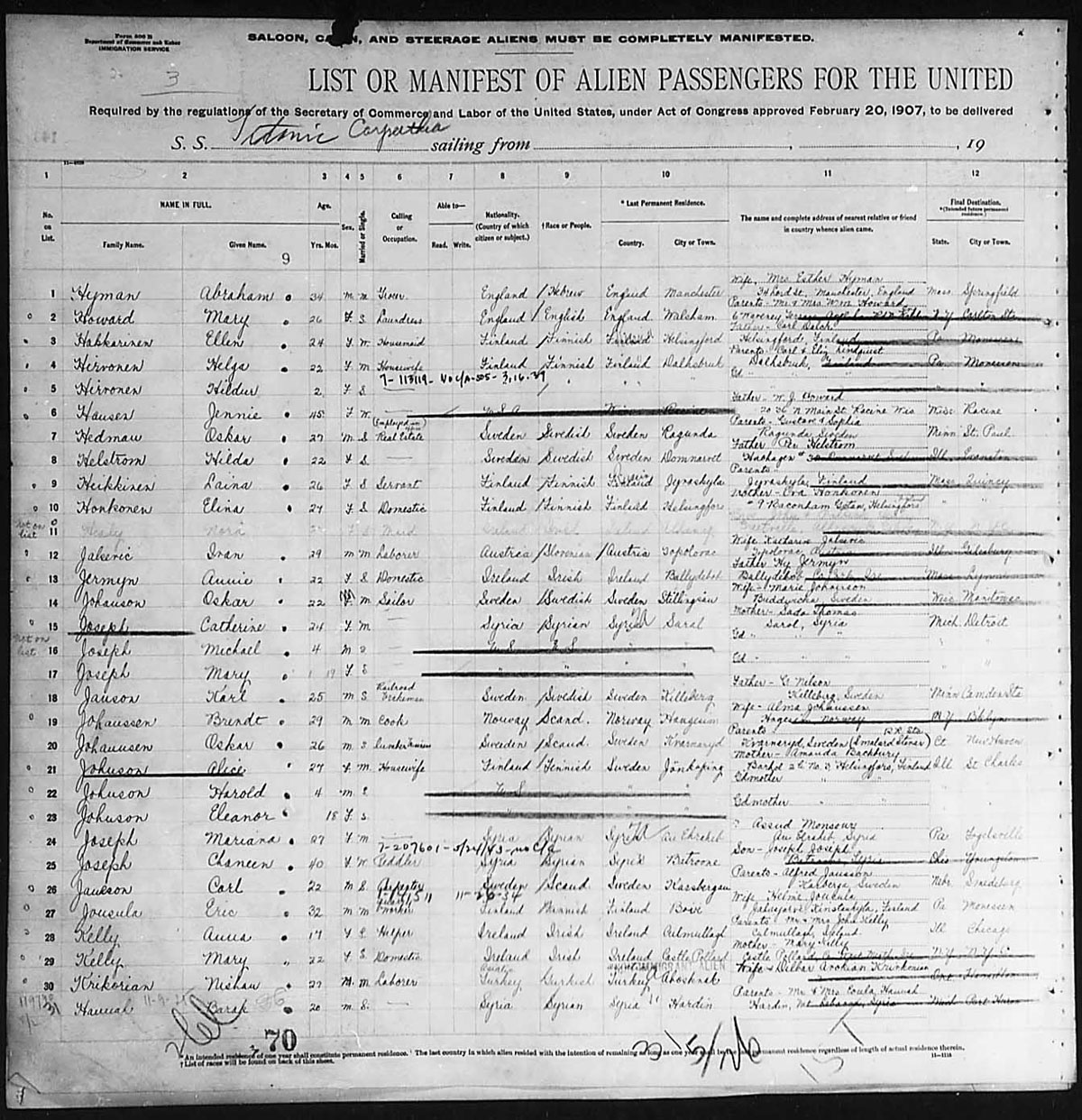

The Carpathia was the lone ship to respond to Titanic's distress signals, risking a field of icebergs in a daring rescue. The Carpathia's passenger manifest includes the names of the 706 persons it picked up from Titanic's lifeboats on the morning of April 15, 1912. The manifests collected by the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization list 29 categories of questions asked of all persons entering the United States, from birthplace to where the person would be staying in the United States.

The Titanic Relief Fund, set up by Ernest P. Bicknell in his capacity as director of the American Red Cross, raised $161,600.95 for Titanic survivors and families of the victims. (the British component raised $2,250,000). According to Red Cross "Titanic Relief Fund" documents in the National Archives:

The Director and other representatives of the Red Cross Committee were present when the Carpathia landed its passengers [at the port of New York on April 18]. The office of the committee was opened on the following morning, equipped with telephone service, printed stationery, the necessary blank forms and record cards, and with a staff of visitors and clerks supplied by the Charity Organization Society. Within two days substantially all the survivors of the third cabin passengers and many of the second cabin passengers had been visited and interviewed in their places of temporary shelter or at the Committee's Office. . . . This was extremely important. because comparatively few of the third cabin passengers remained in New York City.

The highest percentage of victims were steerage, or "third cabin" passengers, who were mainly poor immigrants coming to America. The ethical question of why first-class passengers were allowed to get into lifeboats ahead of those in second and third class became an issue for future investigation.

The unimaginable scale of the disaster led many people to write to the President of the United States. Dozens of letters came to President William H. Taft from citizens who were angered, inspired, or moved by the loss of the Titanic. They demanded an investigation into the sinking, shared ideas for the prevention of such disasters in the future, or expressed sympathy for the death of President Taft's military aide, Maj. Archibald Butt. Butt, one of Taft's closest friends, was returning from a six-week vacation aboard the Titanic, and his leave of absence papers and a copy of a letter of introduction from Taft to Pope Pius X are also in the National Archives.

Congressional Hearings Lead to Legislation, Regulations

Almost immediately after the disaster, a congressional hearing was convened on April 19, 1912. Extensive documentation of the Titanic's voyage is contained within the proceedings of the U.S. Senate's "Titanic Disaster Hearings." The report's 1,042 pages document what a commerce subcommittee learned over its 17-day investigation of the causes of the wreck. The subcommittee's chairman, Senator William Alden Smith (R-Michigan), spoke fervently of why he wished to document the event quickly:

Our course was simple and plain–to gather the facts relating to this disaster while they were still vivid realities. Questions of diverse citizenship gave way to the universal desire for the simple truth. . . . We, of course, recognized that the ship was under a foreign flag; but for the lives of many of our own countrymen had been sacrificed and the safety of many had been put in grave peril, it was vital that the entire matter should be reviewed before an American tribunal if legislative action was to be taken for future guidance on international maritime safety.

The subcommittee interviewed 82 witnesses and investigated everything from the inadequate number of lifeboats to the treatment of passengers riding steerage to the newly operational wireless radio machines. Smith also wanted to know why warnings of icebergs had been ignored.

One of the themes emerging from the "Titanic Disaster Hearings" is the excesses of the "Gilded Age"—wealth, power, and business in a newly technological world gone wild. The hearings were held in the glamorous Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in Manhattan. (Ironically, John Jacob Astor IV, who perished aboard the Titanic, had built the Astoria Hotel, which later became part of the Waldorf-Astoria.)

Opposite the senators sat the first witnesses, White Star's managing director J. Bruce Ismay and other company officials. Ismay was also president of the International Mercantile Marine Company, White Star's American parent company. He was vilified in the press as a monster, as one who had put his own life and safety before that of women and children as the lifeboats were launched.

Throughout the hearings, he remained confident, almost hubristic, regarding the ship's stamina under pressure. In explaining how Titanic's disaster could have been averted, he stated simply, "If this ship had hit the iceberg stern on, in all human probability she would have been here to-day [the stern being the most reinforced part of the ship]."

Instead, he said, the iceberg made "a glancing blow between the end of the forecastle and the captain's bridge." He remained sentimental regarding the ship's demise. In the lifeboat, he rowed the opposite direction of the sinking Titanic: "I did not wish to see her go down. . . . I am glad I did not."

Ismay said the trip was a voluntary one for him, "to see how [the ship] works, and with the idea of seeing how we could improve on her for the next ship which we are building." He told the subcommittee, "We have nothing to conceal, nothing to hide." He was grilled again on the 10th day of the investigation, when he denied reports of speeding up the ship to "get through" fields of ice; other eyewitnesses, however, would contradict him.

Also interviewed the first day was Arthur Henry Rostron, the captain of the Carpathia. Rostron gave detailed information about the circumstances under which Titanic's distress signals had been heard: the wireless operator was undressing for the night but still had his headphones on as the signal came across.

Rostron also related the details of how he prepared the Carpathia to receive the hundreds of survivors in the lifeboats. He came alongside the first lifeboat at 4:10 a.m. on April 15 and rescued the last at 8:30 a.m. He then recruited one of the Carpathia's passengers, an Episcopal clergyman, to hold a prayer service of thankfulness for those rescued and a short burial service for those who were lost.

Rostron would later receive a special trophy as a symbol of gratitude from the survivors of the Titanic. It was presented to him by the legendary "Unsinkable Molly [Margaret] Brown," a wealthy Denver matron who assisted with the lifeboats. Rostron received many other memorials and a Medal of Honor from President Taft.

The outcome of the hearings was a variety of "corrective" legislation for the maritime industry, including new regulations regarding numbers of lifeboats and lifejackets required for passenger vessels. In 1914, as a direct result of the Titanic disaster, the International Ice Patrol was formed; 13 nations support a branch of the U.S. Coast Guard that scouts for the presence of icebergs in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

Survivors, Families Seek Millions from White Star

Beyond simply seeking corrective legislation to prevent future disasters, the survivors and the families of victims also sought redress for loss of life, property, and any injuries sustained. The limited liability law at the time, however, could restrict their claims significantly. The Titanic's liability was protected by an 1851 law ("An Act to limit the Liability of Ship-Owners, and for other Purposes," 9 Stat. 635) designed to encourage shipbuilding and trade by minimizing the risk to owners when disasters occurred.

Under this law, in cases of unavoidable accidents, the company was not liable for any loss of life, property, or injury. If the captain and crew made an error that led to a disaster, but the company was unaware of it, the company's liability was limited to the total of passenger fares, the amount paid for cargo, and any salvaged materials recovered from the wreck. The 706 survivors and the families of the 1,517 dead therefore might be entitled to only a total of $91,805: $85,212 for passengers, $2,073 for cargo, and a $4,520 assessment for the only materials salvaged from the Titanic—the recovered lifeboats.

In October 1912, the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (more commonly known as the White Star Line) filed a petition in the Southern District of New York to limit its liability against any claims for loss of life, property, or injury. In this petition, the White Star Line claimed that the collision was due to an "inevitable accident." "In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship TITANIC" (A55-279) is a part of the National Archives holdings in New York City.

The only way to remove limits on the company's liability would be to prove that the captain and crew were negligent and the ship's owners had knowledge of this fact.

Those individuals seeking payments slowly began to build their case against the White Star Line. They held that although the crew had received wireless messages about the presence of icebergs, the Titanic had maintained its speed, stayed on the same northern course, posted no additional lookouts, and failed to provide the lookouts with binoculars.

In addition, they faulted the White Star Line for not properly training the crew for evacuation, leading to the launching of partially filled lifeboats and the loss of even more lives. For these reasons, combined with the fact that the managing director of the White Star Line, Ismay, was on board the Titanic, claimants believed the liability should be unlimited.

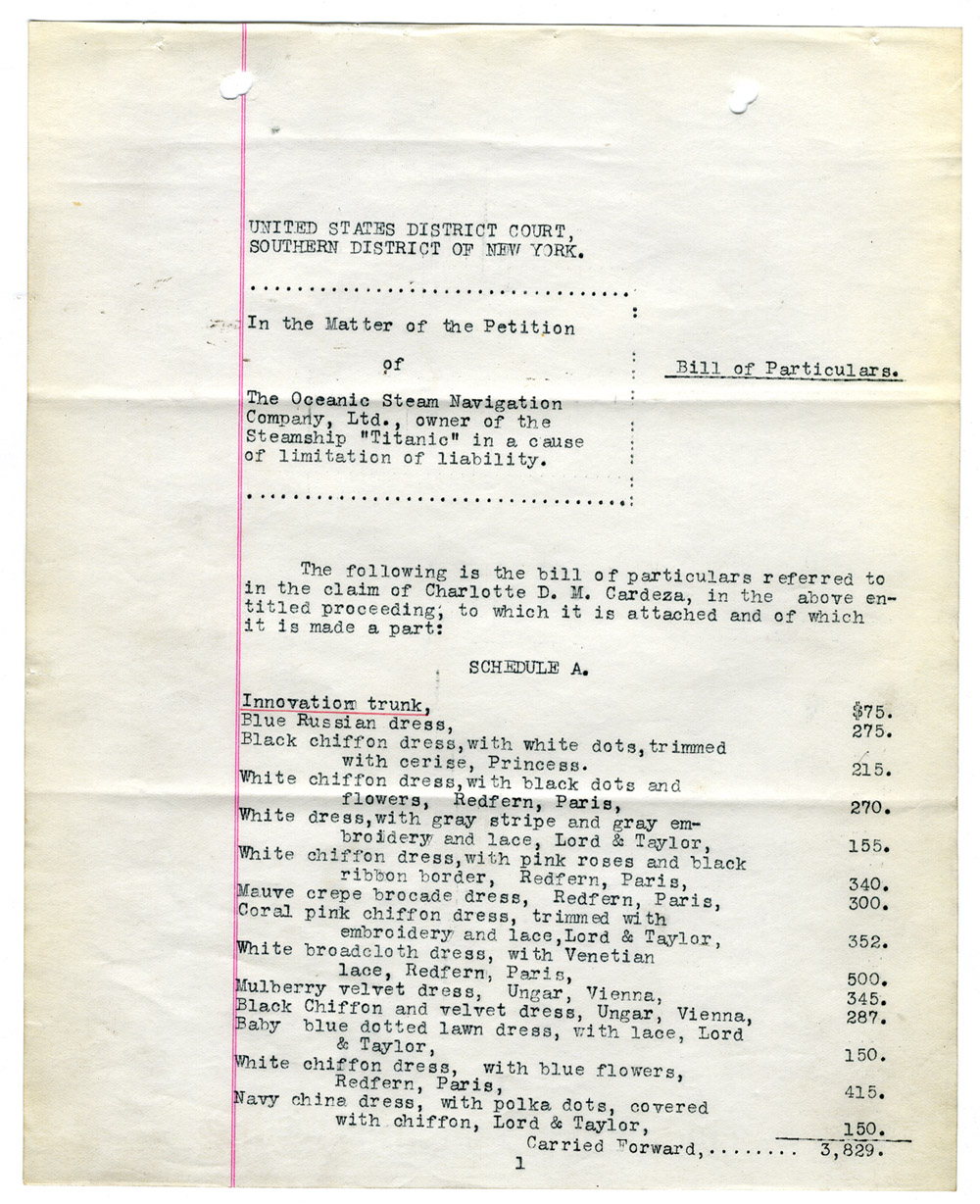

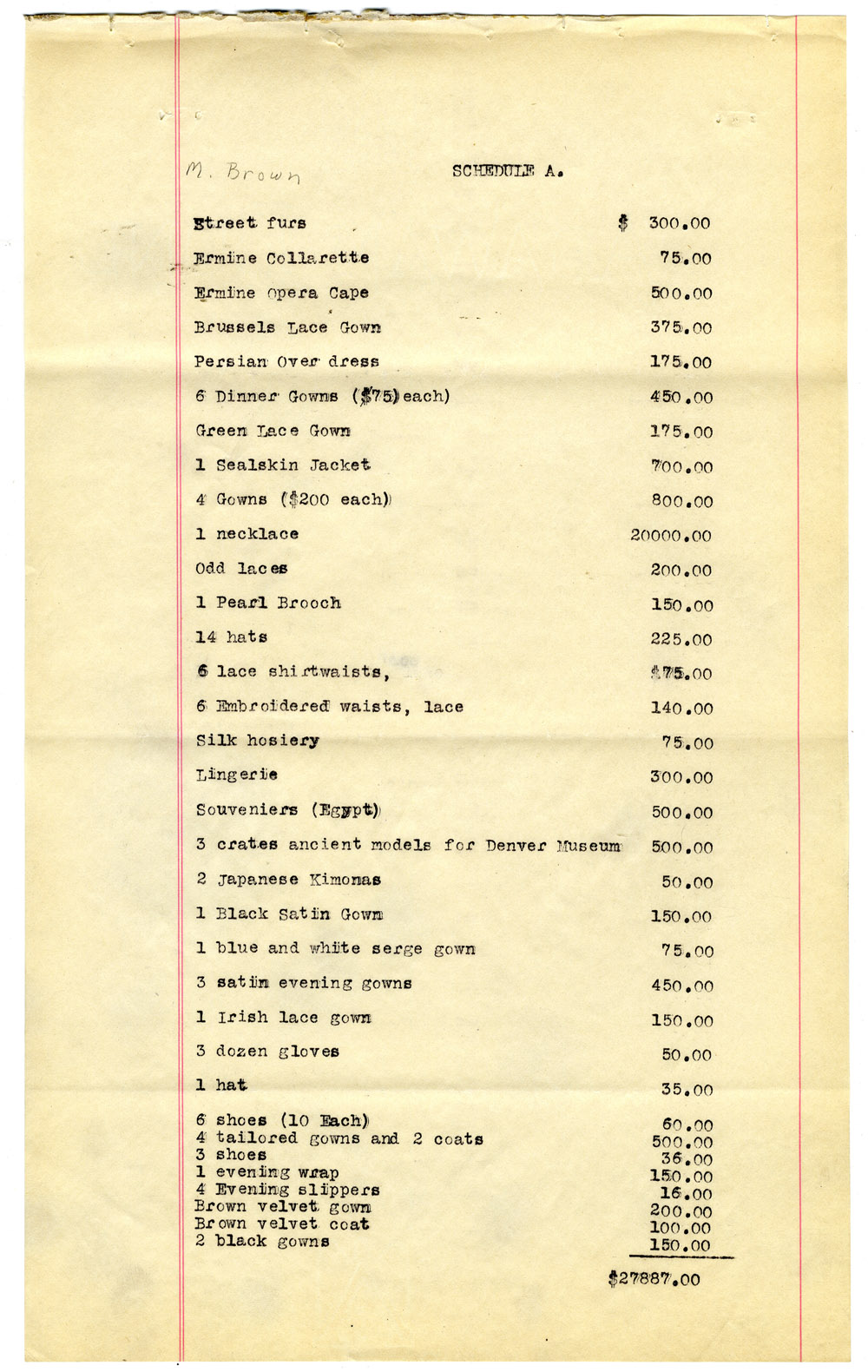

After White Star filed its petition, several notices were placed in the New York Times between October 1912 and January 1913, asking people who claimed damages to prove their claims by April 15, 1913. Hundreds of claims totaling $16,604,731.63 came from people around the world. Claims were divided into four groups: Schedule A: Loss of Life, Schedule B: Loss of Property, Schedule C: Loss of Life and Property, and Schedule D: Injury and Property.

The Schedule D claims for injuries and property detail the harrowing experiences of many survivors of the Titanic. In nearly 50 claims, survivors describe how they lived through the disaster and the physical and mental injuries they sustained.

Anna McGowan of Chicago, Illinois, was unable to get on a lifeboat and jumped from the Titanic onto a lifeboat and sustained permanent injuries from the fall, shock, and frostbite. The experience left her in a state of "nervous prostration" (most likely something similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD) and unable to provide for herself.

Patrick O'Keefe of Ireland also jumped overboard to save his life, but he remained in the cold Atlantic waters for hours before being rescued by lifeboat B.

Bertha Noon of Providence, Rhode Island, asked for more than $25,000 due to injuries she sustained after being pushed onto a lifeboat and being exposed to the cold for several hours before being rescued by the Carpathia. Her injuries included an injured back and spine that left her "unable to wear corsets," severe nervous shock, a "misplaced womb," and a recurring congestion in her head and chest that left her delirious and unconscious for days at a time.

Though the Schedule A claims filed by family members for loss of life did not include first-hand accounts of the accident, they document tragic losses of entire families. Finnish immigrant John Panula was preparing for a reunion with his family in Pennsylvania when his wife and four children died on the Titanic. The Skoogh family with their four children Carl, Harold, Mabel, and Margaret Skoogh (ages 12, 9, 11, and 8 respectively) were returning to the United States aboard the Titanic.

Claims for Losses Reveal Class Differences

The loss of life claims also reveal the variety of values assigned to a human life. While Alfonso Meo's widow, Emily J. Innes-Meo, asked for only £300 (approximately $1,500 at the time), Irene Wallach Harris, the widow of Broadway producer and theater owner Henry B. Harris, sought $1 million in her claim. Some of the documents state the ages and annual salaries of the deceased to justify the amounts they were seeking in their claims. The most detailed claim involved the $4,734.80 claim filed by the family of 41-year-old James Veale:

That the said James Veale was by profession a granite carver; that he was earning at the time of his death $1,000 per year or more. That according to the Northampton Table of Mortality, the said James Veale, deceased probably would have lived, except for his death aforesaid, 11.837 years more; that the said James Veale did not expend upon himself more than $600 a year; that his personal estate has been damaged in the sum of $400 per year during the period of 11.837 years and to the extent of $4,734.80 by reason of the aforesaid breach of contract committed by the petitioner herein as aforesaid.

The claims also reveal the vast class differences apparent among the passengers of the Titanic. This is most apparent in the Schedule B claims for loss of property. The most detailed and largest property claim belongs to socialite Charlotte Drake Cardeza, who occupied the most expensive stateroom on the ship. After surviving the sinking of the Titanic aboard lifeboat 3, Cardeza filed a claim for the lost contents of her 14 trunks, 4 suitcases, and 3 crates of baggage (a total of at least 841 individual items) for a sum of $177,352.75. The nearly 20-page itemized claim includes objects such as her 67/8-carat pink diamond ring valued at $20,000. On the other end of the spectrum, Yum Hee of Hong Kong filed a claim for $91.05. His most expensive item: a suit of clothes valued at £2.5 (approximately $12.50 at the time).

From the claims for loss of property, we also discover that Margaret ("Molly") Brown's three crates of ancient models destined for the Denver Museum, Col. Archibald Gracie's documents concerning the War of 1812, and over 110,000 feet of motion picture film owned by William Harbeck are all now at the bottom of the Atlantic. The most expensive individual item lost during the sinking was H. Bjornstrom-Steffanson's four-foot-by-eight-foot oil painting La Circasienne Au Bain by Blondel, valued by him at $100,000.

Schedule C claim 72 was filed on July 24, 1913, by Mabelle Swift Moore, widow of businessman Clarence Moore. Moore had been a member of a Washington, DC, brokerage firm W. B. Hibbs and Company and owned extensive real estate. A "master" of the hunt, he had been in England looking for a pack of 50 hounds. (The dogs, however, were not carried on the Titanic.) Mrs. Moore sued for $510,000.

Survivors Give Eyewitness Accounts of the Sinking

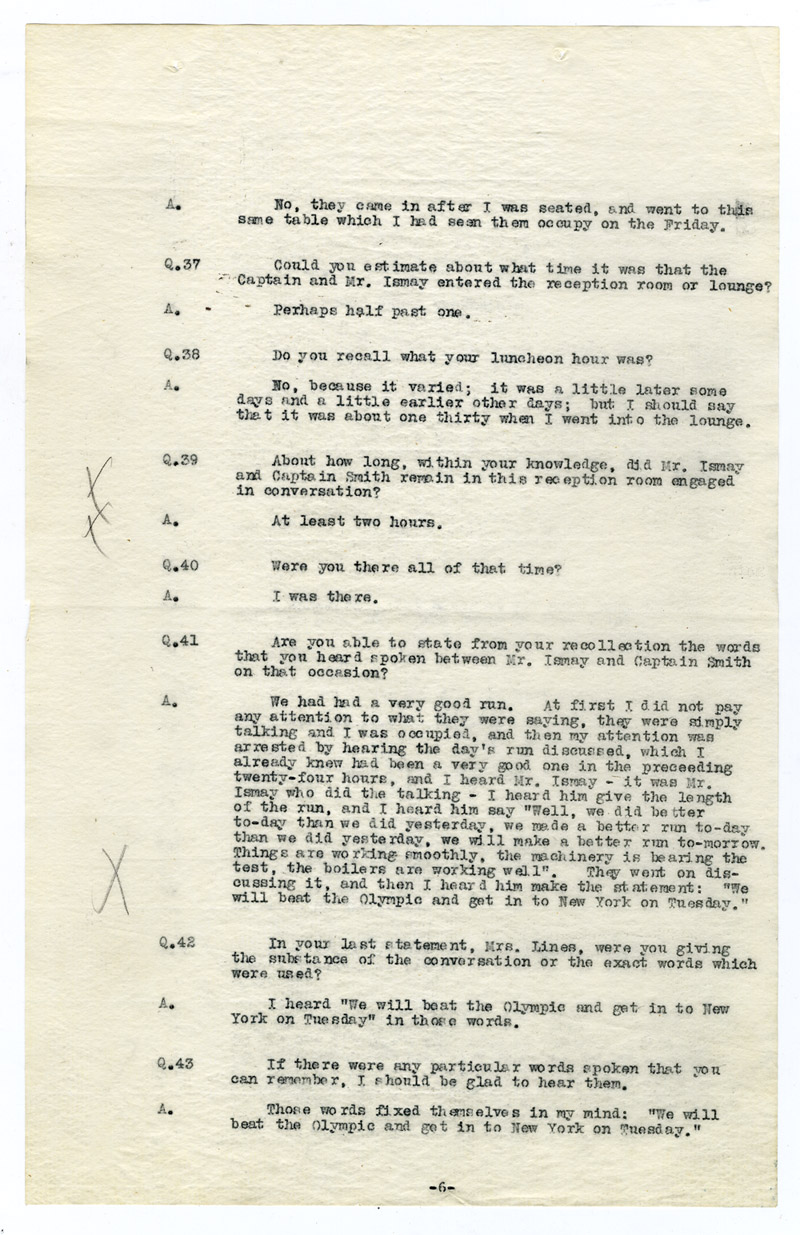

Though the White Star Line filed its petition in October 1912 and individual claims were due by April 1913, hearings were not held in the Southern District of New York until June 1915. Depositions filed with the court throughout 1913 and 1914 provide conflicting reports on blame for the disaster.

In June 1914, White Star Line's Ismay was questioned about the speed of the Titanic, its lifeboats, the lookout, and other issues that may have contributed to the disaster. Throughout his testimony, Ismay restated many of the same opinions given during the congressional hearing—that all decisions were made by Capt. Edward Smith and he was onboard to consider passenger accommodation improvements for the White Star Line's next ship, the Britannic.

Statements by two of the survivors, Elizabeth Lines and Emily Ryerson, seemed to contradict Ismay's statements. Lines declared that she overheard parts of a two-hour conversation between Captain Smith and Ismay on Saturday, April 13. Sticking in her mind was Ismay's statement, "We will beat the Olympic and get in to New York on Tuesday," meaning they would arrive one day earlier than originally planned. The following day, Ryerson recalled Ismay holding a message and stating to her that "We are in among the icebergs." Despite this, he told her that they would be starting up extra boilers that evening to surprise everyone with an early arrival.

Other depositions filed by survivors give us eyewitness accounts to the dramatic and tragic final moments aboard the Titanic. Ryerson described the bitter cold of that April night before being told by a fellow passenger to put on her life belt. Though she described the initial scene on the boat deck as without confusion, the situation changed quickly. Passengers were thrown by crew into the lifeboats; Ryerson even describes falling on top of someone. After lifeboat no. 4 was loaded with 24 women and children (far below the 65 it could hold), it was lowered toward the water. Before being fully lowered, the lifeboat jammed, and men swarmed into the boat, which was intended for women and children only. After being lowered, the survivors and crew began to row for their lives, fearing that the sinking Titanic might suck them down with it. Later on that night, near dawn, Ryerson's boat returned to the site of the sinking and began rescuing some 20 survivors.

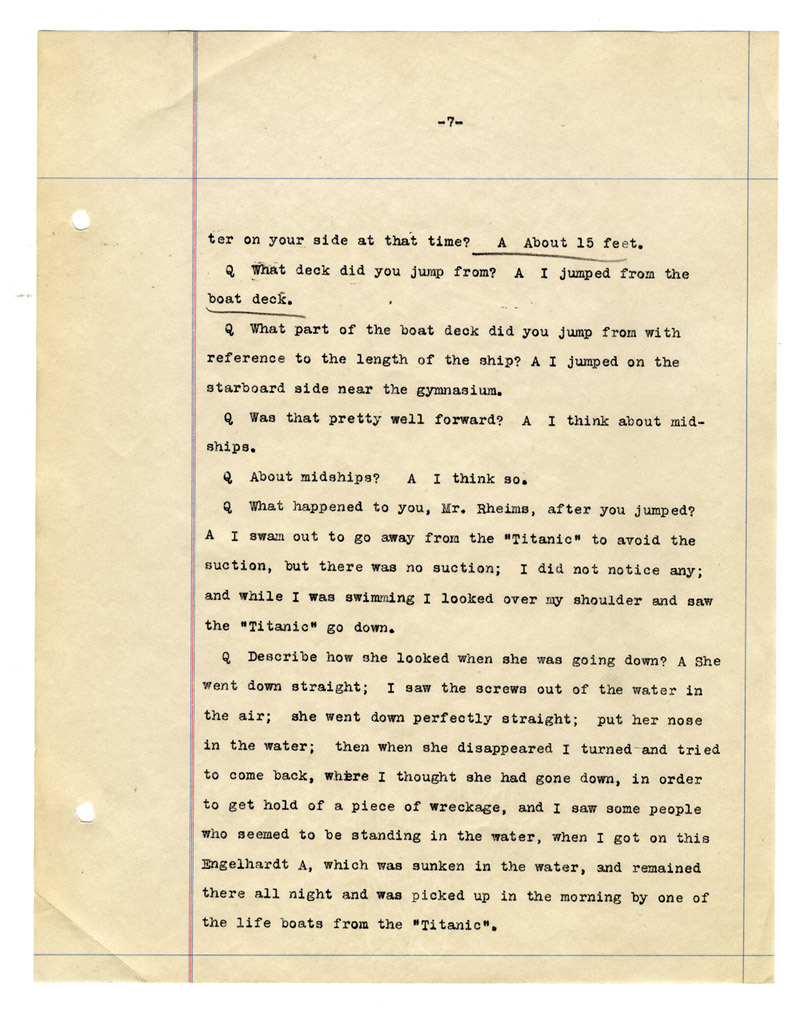

Among those rescued survivors was George Rheims, who remained for some five hours in waist-high water on a partially submerged collapsible lifeboat. In his deposition he recounts how hours earlier, after Rheims noticed "a slight shock" when returning from the bathroom, he looked out the nearest window and saw a massive white iceberg pass by. He then reported witnessing several lifeboats launching that were between half and three-quarters full. He also described seeing men scrambling onto lifeboats as they were lowered and hearing pistols being shot during his last hour aboard the ship. In the final minutes before Titanic disappeared into the depths, Rheims jumped into the cold waters and waited for his rescue.

Over several days in June and July 1915, testimony continued. Negotiations carried on outside of court led to a tentative settlement with nearly all of the claimants in December 1915. The settlement was for a total of $664,000 to be divided among the claimants. A final decree, signed by Judge Julius M. Mayer in July 1916, held the company guiltless of any privity and knowledge and not liable for any loss, damage, injury, destruction, or fatalities.

The Titanic's tragic story fascinated people both at the time of the disaster and for generations after. For more than 70 years, the exact location of the ship's remains was unknown. On September 1, 1985, a joint American and French expedition team found the vessel under more than 12,400 feet of water off the coast of Newfoundland. On November 21 of the same year, Rep. Walter Jones, Sr., of North Carolina, chairman of the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, submitted a report to accompany House Resolution 3272. It recommended that the shipwreck Titanic be designated "as a maritime memorial and to provide for reasonable research, exploration, and, if appropriate, salvage activities."

Perhaps in the end, the 1986 Memorial Act sums it up best by stating, where marine resources are concerned, at least, "we must maintain a sense of perspective regarding man's abilities and nature's powers." Nature's power, in the form of an iceberg in the frigid north Atlantic Ocean one April night in 1912, seems to impress us all the more 100 years later.

Alison Gavin received her M.A. in history from George Mason University in 2004; she was the 2003 Verney Fellow for Nantucket Studies. She has worked in the National Archives since 1995, and her work has appeared in New England Ancestors, Historic Nantucket, Quaker History, and Prologue.

Christopher Zarr is the education specialist for the National Archives at New York City. He works with teachers and students to find and use primary sources in the classroom.

Note on Sources

Learn more about:

- Other Titanic records online

- Stories from the Titanic on the Prologue blog

- The sinking of the Christmas tree ship in Lake Michigan

Additional research for this article was conducted by William Roka at the National Archives at New York City.

The Carpathia's passenger manifests listing survivors of the Titanic are in Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85, at the National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC. They have been microfilmed as T715, Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1897–1957, roll 1883.

The letters to President Taft regarding the disaster are in "Letters Sent by President Taft to the Department of Commerce and Labor," Entry 15, General Records of the Department of Commerce, Record Group (RG) 40, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP).

Archibald Butt's leave of absence papers and a copy of his letter of introduction to Pope Pius X are in Records of the Adjutant General's Office, RG 94, NAB.

The largest and most far-reaching of the documents NARA has concerning the sinking of Titanic (at 1,176 pages) can be found in the United States Congressional Serial Set (serial 6167): U.S. Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce, "Titanic" Disaster: Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce United States Senate, pursuant to S. Res. 283 directing the Committee on Commerce to investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star Liner "Titanic," S.Doc. 726, 62nd Congress, 2nd sess., 1912 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1912), Publications of the U.S. Government, RG 287, NACP.

A more accessible source for the Senate hearings, at only 571-pages, is The Titanic Disaster Hearings: The Official Transcripts of the 1912 Senate Investigation, edited by Tom Kuntz (New York: Pocket Books, 1998). It gives accounts of the 17 days of hearings, an introduction and epilogue, an appendix, a list of witnesses, and a digest of testimony.

The records from the limited liability suits are in the case file "In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship TITANIC"; Admiralty Case Files Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives at New York City.