"We're still alive today"

A Captured Japanese Diary from the Pacific Theater

Summer 2013, Vol. 45, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Jennifer N. Johnson

"We know we are going to die, so we have no fear of anybody and everyone is high-spirited."

—from the diary of a Japanese soldier on Makin Atoll

The Pacific theater in World War II has always intrigued me, perhaps because my grandfather served there, but I never heard any stories from him, as he rarely talked about it.

But then I read the diary of a World War II Japanese soldier. This Japanese soldier's diary gives a stark view of the war in the Pacific, and his recorded thoughts allowed me to better understand the war that my grandfather fought in.

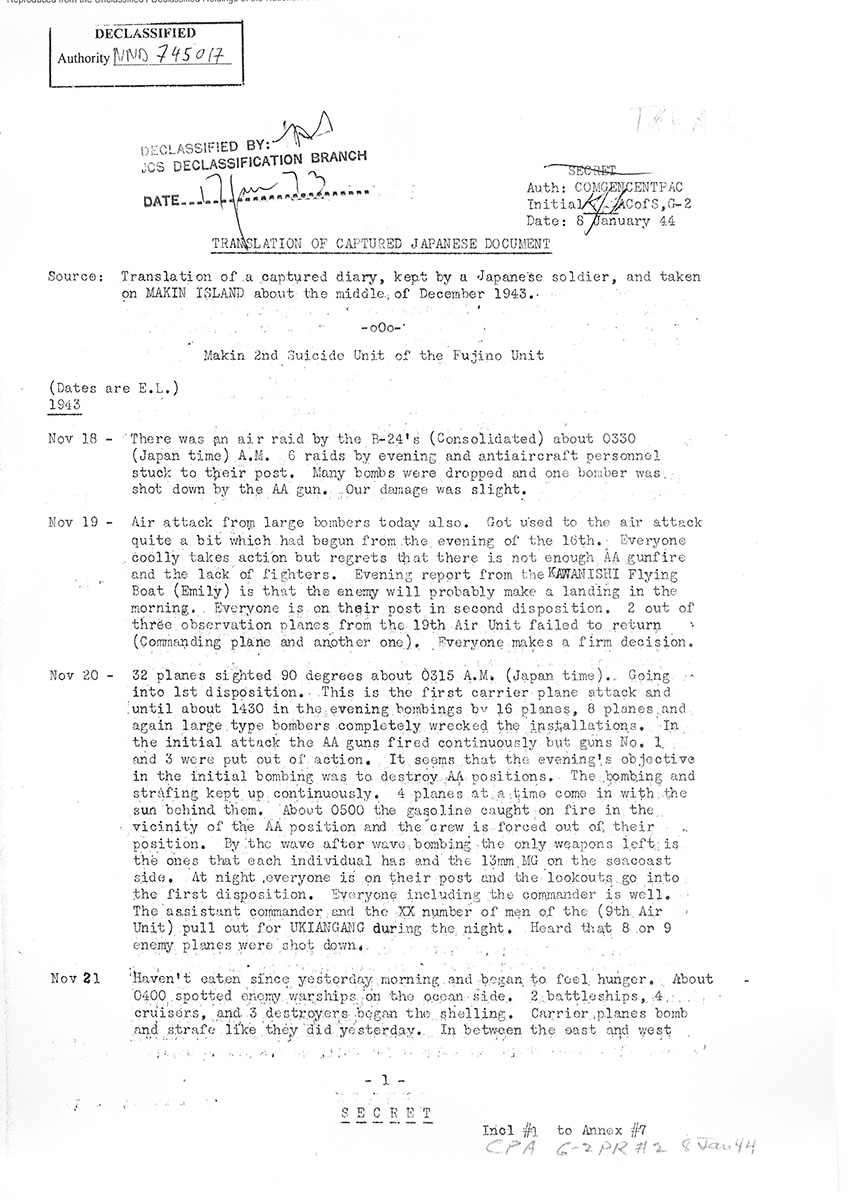

This story begins with the diary's transcript, which lies among the War Department records at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. Translated by U.S. military intelligence, the diary offers a glimpse into one soldier's life among the millions of personal, complex World War II stories. This man, whose training was shaped by Japan's military tradition, wrote his journal as he planned suicide attacks, battled his emotions, and fought to live.

For example, he recorded on November 25, 1943:

"Even though we are alive we figure we will only live about 2–3 days. All of us put the muzzle of the gun to our throats several times but however eventually we will die so why not just stick it out to the finish?"

The diarist, a soldier sent to the Gilbert Islands in the Pacific, was stationed on Makin Atoll, a small group of islands just south of the Marshall Islands. Japan had held Makin, where they had established a seaplane base, since its expansion into the Pacific in 1941. The Gilberts and Marshalls were critical to both Japan and the United States. The islands served as Japan's outer defenses and were, for the United States, vital communication links between Hawaii and Australia.

Makin Atoll, lying little more than 2,000 miles from Pearl Harbor, is a rough triangle enclosing a large lagoon. Makin Island, also called Butaritari, lying south of the lagoon, was the largest and most important piece of land in the atoll and was where the Japanese established their seaplane base.

If the American attack on the Gilberts succeeded, U.S. forces could begin moving toward Japan. Preparations for the attack began in early 1943. The mission would be carried out by a combination of Army, Marine, and Navy forces. Officially called Operation Galvanic, the mission consisted of a northern and a southern landing force. The northern landing force's objective was Makin Atoll, and the southern landing force was to go to Tarawa. The Battle of Tarawa was the first major American offensive in the central Pacific region.

The mission of capturing Makin and eliminating the Japanese in the area required three steps. First, attack the island; second, gain control of all surrounding smaller islands; and third, pursue and capture the enemy.

American troops left Pearl Harbor for Makin Atoll on November 10, 1943. Air attacks preceded them, and the northern landing force arrived at Makin Atoll in the early hours of November 20.

In the diarist's third entry, dated November 20, he first mentions American forces:

32 planes sighted 90 degrees about 0315. . . . This is the first carrier plane attack and until about 1430 in the evening bombings by 16 planes, 8 planes and again large type bombers completely wrecked the installations. . . . 4 planes at a time come in with the sun behind them.

According to an American military preliminary report, about 300 Japanese troops opposed the landing at Makin Atoll. Another 50 aviation personnel and about 250 laborers participated in the defense. Many of the laborers were Korean.

By November 24, the commander of the northern landing force considered the first phase of the operation complete, but much remained to be done. The majority of the Japanese had been captured, and the Americans were preparing to build a landing strip, load the transports to depart, and sweep the small islands for remaining Japanese troops. Two cemeteries, "Gate of Heaven" and "Sleepy Lagoon," were built for the American dead.

The diarist survived and remained uncaptured after the initial assault. His entry from November 24:

The whereabouts of each platoon leader is unknown. We are surrounded by tanks but will stick it out to the finish. . . . We did not care about the fire from the machine guns and the guns on the tanks. . . . The tanks could not come close because of the swamp and men from the labor battalion hastily commit suicide. We're still alive today. We know that we are to die so therefore we are the second suicide unit and plan to fight to the beautiful finish.

For Japanese soldiers, being captured or surrendering was the greatest dishonor. Suicide, not surrender, was the honorable option. In The Anguish of Surrender, author Ulrich Straus describes the prevailing cultural conventions, "It [being taken prisoner] could affect a sister's chance of finding a husband and have an impact on parents, children, and siblings in a myriad of ways, including opportunities for higher education and jobs." In addition, the government declared unofficially that POWs coming home could expect death. This prevailing mentality spurred the Japanese soldiers in combat and helps explain their tenacity in fighting and resisting capture at all costs.

Effective use of propaganda, such as allegations of American cruelty to POWs, further reminded Japanese troops of their duty. According to an Army intelligence report, "The [Japanese] officials told their men of the "extreme cruelty of the Americans." An officer told his men "that if one of them was captured, the Americans would cut off his ears, nose and penis . . . then hospitalize him so he could be sent back to Japan in this condition after the war."

On November 26, he wrote:

Paid respect to the place where the commander was killed. Got about 20 enemy hand grenades and . . . waited for them all day but we did not see them. . . . We can hear some gun fire from all directions . . . and out morale goes up. Today we filled ourselves up for the first time on chocolate, beef, sugar, and bread which was left by the enemy. . . . The whole day passed but we did not see friend or foe.

As tanks and infantry swept Makin and the surrounding small islands to look for survivors, work began on a landing strip and base that eventually supported over 5,000 men and 75 aircraft.

As the Americans proceeded, the diarist and others built rafts and canoes to travel from island to island, evading capture and waiting for reinforcements. By December 2, their boat had no sail, rendering it unusable. They did not believe reports from native islanders about the war's progress in favor of the United States.

[December 2]

We are determined and plan to battle against the tanks if we did not see our forces come in by December 8th's anniversary. . . . It seems that the Americans are giving a lot of false propaganda—American forces have landed in the Marshalls and will soon invade Japan. They told them [the natives] that there were several 10,000 landed at Tarawa and also they told them that if Japanese soldiers come to the village to tell them to give up—(afterthought) don't make me laugh. . . . We can die anytime.

[December 3]

We are still in high spirits and there is little food left and we are determined to make it last until the 8th. We would like to stick it out until the end a little more and let our forces know the courage of the commander and subordinates. As our last hope we are waiting for the power of god. . . . The place where a soldier dies is very important.

He had joined with men from another unit. As they scattered from island to island, they encountered American forces. One morning, after a breakfast of coconuts, the diarist, carrying a hand grenade, left to use the latrine. As he returned, he heard shots and several people shouting.

[December 4]

Hurriedly I came back but it was too late. . . . Atobe was left behind and shot off 5 rounds and reloaded another clip and tried to commit suicide, and I said, "Wait!" "there is more ammunition" left. . . . We opened a can of food and ate it and with rifle and ammunition we went out to the beach. At that time, Engineer Nakada was not quite dead and was suffering so we finished him off with one round. This is also showing our love for a comrade . . . that he will not be taken prisoner.

Because of rain and cold weather, the remaining men were holed up in a native hut for several days. On the two-year anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the diarist was still sailing from island to island, hoping to get closer to Japan, because even dying a few feet closer to home was better. Because of the difference in time zones, December 8 marks the beginning of the war for Japan and the diarist.

[December 7]

This morning the weather is good and 10 of us finish breakfast in high spirits . . . two enemy tanks approach the island. Everyone was separated.We do not have any weapons. I and two others from the 14th Air Unit were hiding in the . . . entrance of an air raid shelter and they passed us three times about 3 meters distance from us. The tanks stayed on the island from 6:00 am until sundown. [He and four others attempted to go to another island.] We swam for about two hours and due to the large waves we were completely exhausted and thinking it was impossible we turned back. Finally the end has come and it is impossible to commit suicide. . . . Enemy tanks with infantry came up about 50 meters away. Don't know why but the four got up and ran into the sea. The tanks opened up with their guns. . . . Maybe the four were either killed or were out of range. God has saved me again. I am all alone and it is pretty lonely.

[December 8]

Today is the 2nd anniversary of the great Asiatic war. . . . I looked around for signs of others being killed but did not find any so my morale went up when I thought they were still alive. Ate coconuts and rested on the ocean side. Waited for my shirt, trousers, and socks to dry. . . . I went around the island [looking for others, he did not find them] and finally determined to commit suicide. When I started to go back, someone called and it was Komatsu, Atobe, and Nozuchi. They had finally completed a raft and were about to start out. It must have been the help of the good god. I regained my courage again.

The diarist's comrades changed often. For the next five days, they roamed from island to island, evading capture from American troops. He wrote how weak he was and that among him and his remaining comrades, they carried one rusted rifle. Waiting for the weather and tide to work in their favor, they hoped to sail to a nearby island.

His last entry is on December 13, roughly three weeks after the initial assault on Makin.

[December 13]

Terrific squall in the morning. Spent whole day in the hut. Departure to be tomorrow. For the first time we wash our face and hands with soap. Plan to go to Kuma [nearby island] in the night.

Then, his diary stops.

Sifting through the numerous military reports written about this mission, I came across other translated diaries. One Army report states that a lone Japanese soldier was picked up in the vicinity of where the diarist said he was in his last entry. Did the writer commit suicide? Did American forces kill him? Did he survive and make it home? I suspect the latter is unlikely. I don't even know his name.

People often assume that their research will complete the story. I have not unlocked the mystery of either my grandfather or this Japanese soldier. Some stories are never finished.

Jennifer N. Johnson is a curator at the National Archives Museum in Washington, DC. She has a Masters in Library and Information Science from the University of Maryland, and a B.A. in History from Texas State University.

Note on Sources

The Japanese soldier's diary is in Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Record Group 165. Greg Bradsher, an archivist at the National Archives at College Park, came across it several years ago while looking for something else. Intrigued by it, he hoped to someday identify the diarist or find out what happened to him. Although I did not discover anything more about the diarist, my research—not only in his diary but in military reports, interviews, and other captured diaries—revealed much more about what he endured.

The World War II operations reports found in Records of the Adjutant General's Office, RG 407, were invaluable to me in piecing together the details of the mission, submitted before, during, and after. There were several reports for each phase that provided real-time observations: how the mission was going, how it would proceed, and lessons learned, along with maps and photos. It was through these reports that I learned that most of the laborers were Korean. In Records of the Army Staff, RG 319, in the series Records of the Office of Chief Military History is a history of the Makin Operation. I consulted several books, but the one that was immensely helpful in capturing the mindset and Japanese military tradition was Ulrich Strauss's The Anguish of Surrender (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004).