Discovering Your Neighborhood

How to Use National Archives Records to Find Out More about Where You Live

Fall 2015, Vol. 47, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By M. Marie Maxwell

Many people use the United States census to discover their family roots, but these same tools can be used to discover a neighborhood’s background.

Just as you may be intrigued to discover that your great-grandfather was a miner, you may get that same thrill of discovery to find out that your house, your street, and maybe your block was home to immigrant factory workers. You share blood with your ancestors; you share a place with your neighbors from the past.

There is nothing out of the ordinary about the Truxton Circle neighborhood in Washington, D.C. As far as I know, no famous people lived there. It houses no embassies, nor has it been the location of any notable historical event. It is special only because I live there and wondered what kind of neighborhood this was and who lived here.

To answer these questions, I went to the census.

Census records, with their questions about an individual's race, occupation, parents' place of birth, and other details, are a treasure trove of information for genealogists, who use them to find family relations. But these details, when combined with their neighbors' particulars, can provide an image of a neighborhood, complete with class and racial composition. The census is the best source for this research since it attempts to capture all residents regardless of race, gender, occupation, or lack thereof.

Shaw is a very large neighborhood in Washington, D.C. Even though the history of the neighborhood is as old as the capital city itself, the borders of Shaw are a 1960s construct. The National Capital Planning Commission defined Shaw as the area serviced by the Shaw Junior High School and those borders stretched to North Capitol Street.

In 1967 the Washington Post published a map showing the borders of Shaw as 14th, Florida, North Capitol, and M Streets, NW. Within these borders are several subsections such as Logan Circle, U Street, Blagden Alley, parts of Mount Vernon Square, and Truxton Circle.

Truxton Circle, as the modern city defines it, sits within the northeastern boundaries of Shaw, between three major roads. On the north is Florida Avenue, known in the 1800s as Boundary Street. Boundary Street separates Old City, where Truxton Circle lies, from the various "suburban" District neighborhoods such as Eckington and LeDroit Park, which began to appear around the late 19th century. For this study, the eastern border is North Capitol Street, which separates Northwest Washington from Northeast. The Truxton Circle traffic circle sat at the intersection of Boundary and North Capitol.

The Truxton Circle area proved to be a suitable section to investigate for two reasons. First, there is an absence of literature regarding this portion of Shaw. Second, Truxton Circle blossomed from more than 100 households in 1880 to more than several thousand households in 1940, creating a statistically solid but manageable number of residences.

Collecting the Data from Census Rolls

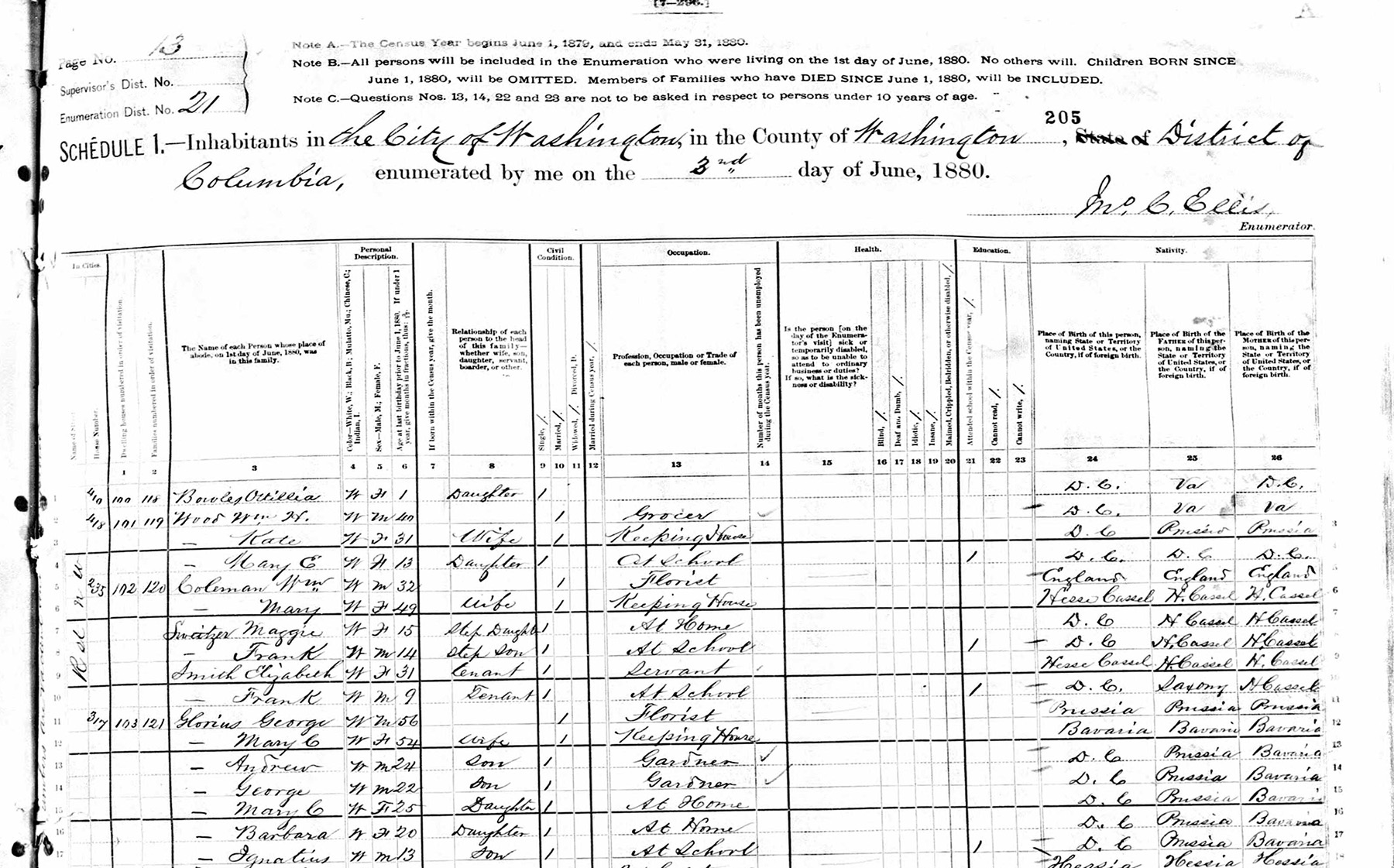

The project draws heavily from the United States census, in particular the 1880, or 10th census. The area of Truxton Circle falls within the 21st and 29th enumeration districts. For every Truxton Circle address falling within the search area, I collected every bit of data from the census rolls. I arranged each address by city square and mapped data regarding the household head and spouse’s race.

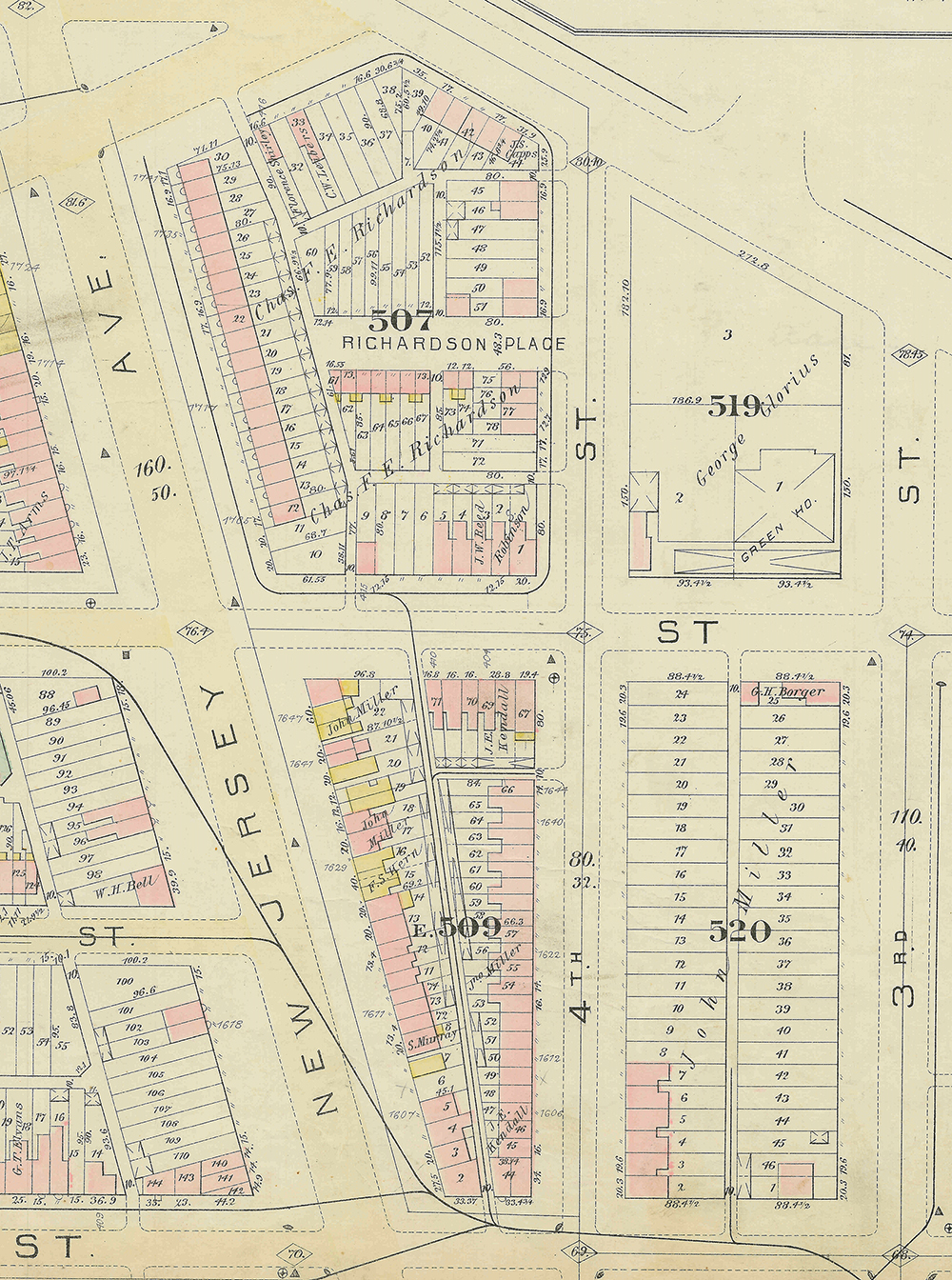

Mapping proved difficult as real estate and fire maps do not always have house addresses. The 1887 Hopkins real estate maps were the main source because they outline houses, illustrating what was brick, wood, or a shed, and indicate major institutions such as schools, churches, and hospitals. Like regular city maps they show street names, street widths, major sewer lines, relative widths of alleys, square numbers, lot numbers, and sometimes house numbers. For tax and real estate purposes in the District of Columbia, property is identified by square or plat and lot number, not by address.

In addition to using maps, walking around the neighborhood was useful. Several of the buildings that existed at the time of the 1880 census still stand, and it helped to venture outside and see if the building was a small two-story Federal or a sizeable three-story Victorian. There is no guarantee, however, that the building now standing at an address is the same one from 1880. Regardless, a visual inspection reveals if the property had a basement apartment, which may or may not have existed at the time of the 1880 census.

Truxton Circle in Black and White

What was the character of the neighborhood?

This can be answered by looking at those who lived in it and their relationship to each other. Was Truxton Circle a historically black neighborhood, like it was in the mid-20th century? A working-class neighborhood? Looking at the people and the patterns of segregation can answer that question.

Of the 19 occupied blocks in Truxton Circle, three (Squares 507, 519 and 520) did not have any African American households or recorded occupants. Of those three, two were sparsely populated. On the 1887 Hopkins map, on Square 519 there are three shed structures, one identified as a greenhouse, and one brick building, that was the home of florist and Prussian immigrant George Glorius, who lived there with his wife and five children. Glorius's house, greenhouse, and sheds are the only structures on the square. The nature of his work explains why he had the whole block.

The other sparse block of Square 520 had two households. The first belonged to James Reeves, a Maryland-born white man living alone at 305 Q Street. The only structure facing the odd-numbered side of Q Street, where 305 should have sat, is shown as a shed on the Hopkins map. What sits on that spot today is a bricked-up two-story garage. At that location lived John Miller, a French retired gardener, with his Prussian wife and their three American-born children and a bachelor. On the 1887 map a John Miller is shown to have owned almost all of Square 520, and several properties on neighboring Square 509E.

On Square 507, the households lived on the 1700 block of New Jersey Avenue and the 400 block of Boundary Street. A great many of the heads of those households worked as clerks or held other white-collar jobs.

Square 617 was the only block where African Americans were the only residents. Curiously, of the 41 people who lived on this square, 16 people, representing five households, resided at 78 O Street. If the unit block of O Street structures seen in the 1887 map is any guide to the size of the house, 78 O Street appears to have been a very small structure. Because later fire maps from the early 20th century do not show any structures where 78 O sits, the current residence does not give any inkling of the size of the 19th-century building.

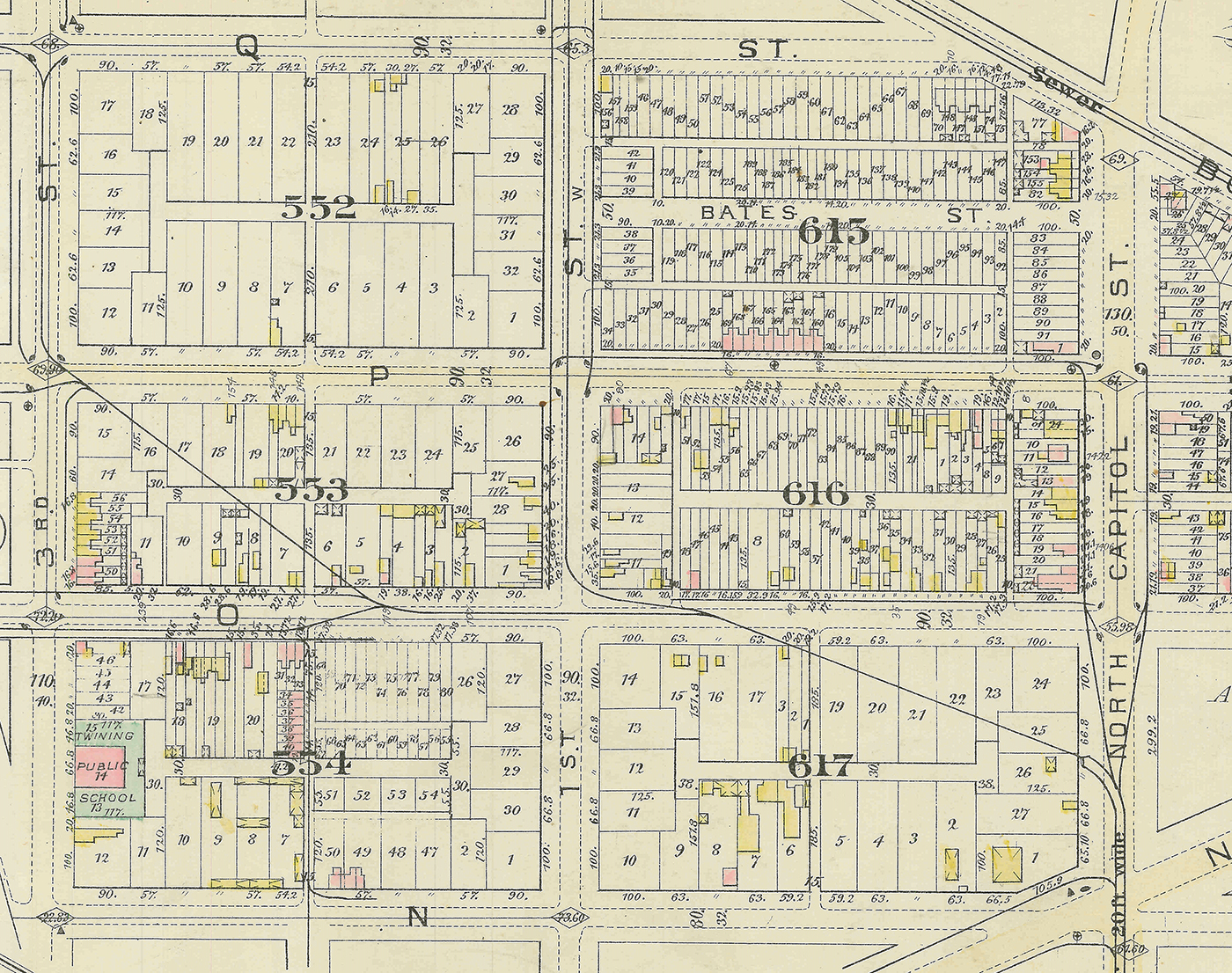

Even though Truxton Circle was sparsely populated in parts, compared to block west of New Jersey Avenue in the rest of Shaw, there was typically someone of a different race living across the street or down the street or on the next block. The unit block to the 200 block of O, 100 block of P, 200 block of R, and the 1400 blocks of Third and First streets had instances of blacks and whites living across the street from each other. Of those, only the 100 block of P, Squares 552 and 553, had whites on both sides of the street.

Because it is hard to see a pattern when there are only a few occupied residences on a street, I looked at blocks with streets that had five or more addresses on one side. The even-numbered unit block of O, where the crowded 78 O Street sat, and the 1400 block of First Street are two of the streets with African Americans on one side. The odd-numbered 1700 block of New Jersey, even-numbered 1400 block of North Capitol, odd-numbered 1400 block, and 1600 block of Third street contained a number of homes, which were all occupied by white residents.

The other occupied blocks or streets had a mix of black and white households, with the races grouped in clumps. Various patterns of clustering occurred with one race on one street or one end of the street, or in a grouping of households. In other instances, there was a mix of one race living in between or near a larger cluster of another race.

For example, the row of six houses from 1408 to 1418 Third Street held African Americans; at the end of the row lived a white family in 1420. Across the alley were two more white-occupied houses.

Passing two vacant lots, at the end of O Street, were a black family at 1430 and Beulah Baptist Church, which was a black church. Among white householders, there were further breakdowns by nationalities, with concentrations of Germans and German Americans and Irish and Irish Americans.

Immigrant Families and Ethnic Divides

Truxton Circle in 1880 was ethnically diverse. Besides having a population of black and white residents, the white residents included a number of immigrant and first-generation Americans. (This project focused on heads of the household and their spouses' nativity and parentage.)

Sixty-two households in Truxton Circle had German or German-American heads or spouses. Several Germanic households clustered around the corners of O, North Capitol, and P Streets, NW, on Square 616. Moving north on Square 615 to North Capitol Street, we find three other German households but not a large or concentrated cluster; the row had one Irish spouse and two native white households. On the eastern side of Square 616 were 20 German or German-American households with a strong presence on the 1400 block of North Capitol Street.

Clustering near the corner on the unit block of P Street were the Stroups, the Plowmans, the Peters, the Haufmans, the Stefels, and the Steidets. Among their ranks were a laborer, a journeyman baker, a huckster (peddler), retail grocer, a tailor, and a journeyman painter. The houses from 12 to 22 P Street were a solid block of German immigrants where both spouses were German. At 24 P Street lived a native white family that provided a pause in this line of Germans, which continued on to 26 and 28 P Street.

The western end of Square 616, where O and P Streets met First Street, had an African American cluster.

Harry Tilghman's family at 66 P Street began the cluster, which continued for five more addresses ending at 78 P Street. These families came from the surrounding states of Virginia and Maryland. The only District natives among them would be the children. Matching addresses to properties, it appears a large space on the corner of First and P broke up the cluster. The northernmost house on this part of the street, 1425 First Street, sat isolated from the other black families on the street. The next six black households on O Street are separated from each other by several properties and one Irish immigrant family.

The racial pattern on Square 616 shows whites on the eastern end of the block and blacks on the western section. White households on this block had a predominately Germanic background. The lines where the races met was near the middle of the block, but it is not a hard line as two white households on O Street are intermixed with the seven black households.

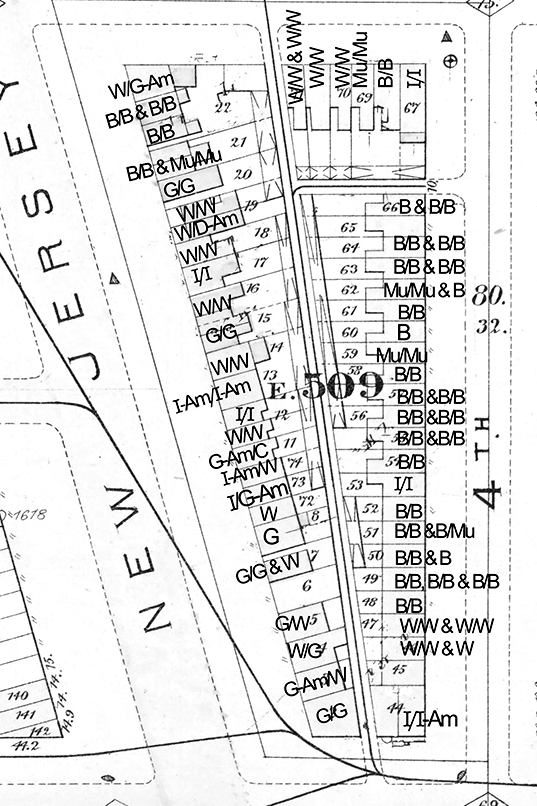

Square 509E was another densely populated block in 1880. The New Jersey Avenue side was predominately white and Fourth Street primarily black. Unlike Square 616, there are not any large clusters of Germans. There was a small cluster on the southern end of the square from 1601 to 1613 New Jersey, but four native whites and one Irishman balance it out.

From the southern tip of Square 509E at 1601 New Jersey Avenue to nearly the northern end at 1639 lived a long string of white families. Among the 22 white households were eight white families or heads born in the United States, and five German-headed households and two Irish-headed households wherein both the head and spouse (if present) were immigrants.

The households with German and Irish backgrounds were fairly intermixed with each other and native white families. Unlike their neighbors to the north on the 1700 block of New Jersey Avenue, there wasn't a single clerk among the heads of these households. They were a mix of tradesmen, policemen, and laborers. David Donigan, an Irish American at 1623 New Jersey, and August Schultz, a German American at 1617, were listed as police officers. There were six carpenters, most of them native whites.

At the northern end of the street lived six African American families residing at three addresses from 1641 to 1647 New Jersey Avenue. George Williams, a 50-year-old laborer from Alabama, lived at 1641 with his 40-year-old wife, Catherine, from Virginia. Next door to their south was August Plitt, a baker from Germany, his wife, and their seven children.

The Williamses appear to have shared the house with laborer Henry Johnson's wife and their three-year-old son, all from Virginia. Also doubling up at 1645 lived laborer Buckman Powell's wife and two children and another family listed as his boarders. At 1647 New Jersey Avenue were two other black families sharing one house. All the men over 18 years old in this group were listed as laborers. The only other occupation was that of servant, held by 1647 New Jersey Avenue resident William Weddington's teenage son. Servant and laborer are two very common jobs for African Americans in this study.

Around the corner on R Street, Square 509E's northern street, was a small block of black and white residents. On the corner of New Jersey and R at 418 R Street lived the American-born three-person household of D.C. retail grocer William Wood. At 410 lived nine people in two households, both headed by native white carpenters. In the next two houses, 408 and 406, resided native white families, followed by two African American households. Mulatto laborer Archibald Moulton lived at 404 with his wife and three female boarders.

The building at 402 R lists three households, but it appears that Henry Hughs, a black laborer, and his wife took in tenants: John Bulter and his wife and his stepdaughter as well as Eliza Downey, a laundress. On the corner of Fourth and R, at 400 R Street, grocer Charles Pearson, an Irish immigrant, lived with his wife, also from Ireland, and their four children.

Toward the rear of the Pearson house and across the alley was Truxton Circle's largest African American cluster, on the even-numbered side of the 1600 block of Fourth Street. Like their counterparts on the northern end of New Jersey Avenue, there were plenty of families doubling up. Of the 17 black addresses on Fourth Street, 11 of them had two or more households living under one roof. At 1610 and 1632 Fourth Street the census lists three households. Both of these addresses housed nine people each, and if the current structures at these addresses have remained unchanged for the last 125 years, the people at 1610 may have lived more comfortably as that house has a basement apartment. Along this side of Fourth Street, houses were small two-story Federals, with two bedrooms on the top floor and about 1,000 square feet of living space if no basement was present. Of 13 houses whose modern equivalents do not have basements, 9 housed 8 or more people, with the highest number (13) residing at 1640 Fourth Street.

Also like the New Jersey Avenue African Americans, many of the male heads of households were listed as laborers. There were a few exceptions. Jarrett Wallace at 1614 Fourth Street, Charles Davis of 1626, and Farley Thornton of 1636 were shoemakers. William Wheeler at 1624 was a carpenter, and Robert Beans of 1638 was a huckster. There also a few female-headed households and some single tenants. A common occupation of working women on Fourth Street was laundress or servant, which is a pattern throughout the neighborhood. Most women, black and white, in the 1880 census were listed as "keeping house." Sometimes daughters and, rarely, wives would hold jobs. At 1614, laundress Rachel Tontee and her two sisters, listed as servants, lived together as tenants. At 1622 Fourth Street, 55-year-old widow Elise Carrol was keeping house while her eldest daughter, also a widow, and Carrol's younger single daughters worked as servants. In that same house lived laundress Mary Hull, another widow, and her adult son, a laborer, and her school-aged daughter. Next door, laborer William Todd's wife worked as a laundress. Widow Francis Washington, Farley Thornton's tenant at 1636, was a laundress. If Elizabeth Clark-Lewis's book Living In, Living Out on African American domestic life during the great migration holds true for 1880 domestics, laundress was a far better position than that of servant. Laundresses were more independent and had greater control over which jobs they took. Laundress was also a step above a "washerwoman" who did the laundry in her home to supplement her income. The laundress provided her services “on site” and had the respect of her employers and other domestics.

Key to map of Square 509E

/ = married couple

& = other households at same address

W = White, American born to American parents

B = Black, African American

Mu = Mulatto, African American

C = Canadian

D-Am = Danish American

G = German

G-Am = German American

I = Irish

I-Am = Irish American

The 1600 block of Fourth Street would be complete stretches of black households were it not for three white households on the southern tip and one Irish household near the middle. Sandwiched between 12 African American addresses to the north and five black addresses to the south was 1618 Fourth Street, where police officer Thomas Lawlor and his wife, both from Ireland, lived with their two D.C.-born children. Farther down the street at 1606 were the Tarltons and the Adamses, and at 1604 were the Sampsons and nurse French, all native white families. At the very end of the block, breaking the mold of typical female jobs, was the Irish immigrant and widow Mary Barry, a retail grocer and head of her household. She lived on the corner of Fourth and R with her six D.C.-born children, ages ranging from 4 to 16, and her Virginia-born sister Ellen Nelligan, who stayed at home.

A small group of black households were book-ended by several white families on the northern end of Square 509E and one large group on Fourth Street. Whites had the southern tip of the square and most of New Jersey Avenue, and small groups of blacks lived on the northern end. On New Jersey Avenue the dividing line of black and white lay between 1606 and 1608. On Fourth Street it is almost all black from 1608 to 1644 with the exception of 1618.

Square 553 was a block with two patterns of segregation. The 1400 block of Third Street had no black families among its 12 households. Of those, eight were solely white natives. At 1417 Third Street a German couple and their seven children shared a house with Thomas Bryons, an Irish painter, who was listed as separate household. The only other immigrants on the street were 1401’s Catherine Ginter from Ireland and 1407’s Anna Stein of Germany, both married to native whites. Around the corner on P Street, in the middle of the block was a collection of seven white households. They were a mix of German Americans, Irish immigrants, and native whites. They and the other Third Street male breadwinners were skilled laborers and tradesmen with one government clerk among them. The 1400 block of First and the 100 to 200 block of O were primarily black. Clusters of African-American households sandwiched an Irish/Irish-American household on the corner of First and O. The male household heads in this African-American cluster were laborers with a few skilled tradesmen among them.

Noticeably, the Irish are everywhere in Truxton Circle. Irish immigrants appear on predominately black streets, white streets, and among German clusters. A small Irish cluster on Square 554 on the 200 block of O Street consisted of five immigrant households, with a native white and a British household between them. Four black households also lived on one end of that block of O Street. The African American Curtis family in 216 O lived next door to the widow Johanna Hack in 218, an Irish immigrant and her family. Mrs. Hack supported her three children as a washerwoman. Irishman John Sullivan, at 220, like several of his African-American neighbors, worked as a laborer. Breaking the row of Irish in 222 was a young waiter from a white Virginia family, his English wife, and their two children. From 224 to 228 were other Irish-born residents: a widow, a laborer, his wife, and their seven American children, and another laborer, his wife, their two kids and his mother.

* * *

The tools genealogists use to uncover clues about their ancestors also revealed evidence of the types of people who lived in my neighborhood. I have learned something about the ordinary men and women who shared the place I call home. This snapshot of Truxton Circle in 1880 shows an area that as a whole was racially mixed. The neighborhood had a blue-collar, working-class character with more domestic servants, laborers, and tradesmen than clerks or other professionals. In total, the Truxton Circle neighborhood was 57 percent white and 43 percent black. (The District of Columbia as a whole was about 67 percent white and 33 percent black in 1880.) Native-born whites, immigrants, and blacks in this area were neighbors.

The census and old real estate or fire maps can help you discover your neighborhood. Start small with your street or block and expand from there. If your neighborhood existed before 1940, there is an available census for you. Several online genealogical tools can help you find the enumeration district for your area. The census from 1880 onwards lists addresses, and neighbors will be listed on the same or adjoining pages.

Creative exploration of sources normally used for genealogy, especially census schedules, can teach us much about past communities and the racial and economic networks in which our ancestors lived. Researchers can add information about individuals and families by exploring other federal records such as immigration, naturalization, military service, and court records. In the end, we can gain a better picture of the history of the neighborhoods in which we live and find a connection with our neighbors from the past.

M. Marie Maxwell is an archives specialist in NARA’s Research Services Division, Textual Processing, in Washington, D.C. She has shared her knowledge of neighborhood history to community groups, at conferences, and on the Web. She received her M.A. in history from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and her M.L.S. with a specialty in archives from the University of Maryland–College Park.

Sources

Tenth Census of the United States, 1880: District of Columbia (National Archives Microfilm Publication T9, rolls 121–122); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group (RG) 29, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Department of the Interior, Census Office, Report on the Social Statistics of Cities, Part II: Southern and Western States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1887).

Elizabeth Clark-Lewis. Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration (New York: Kodansha International, 1996).

Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation's Capital (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967).

Map, Washington, DC, North, Vol. 20, Plate 15, Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, RG 351, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP).

Map, City of Washington, 859, 1888, Records of the Coast and Geodetic Survey, RG 23, NACP.