A Gateway to the West

Fall 2016, Vol. 48, No. 3

By Kimberlee N. Ried

It rises gracefully toward the sky, then elegantly curves back toward Earth as the combined waters of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers swiftly flow by at its base—a symbol of the accomplishments and dreams that drive the American experience.

This is the world’s tallest arch, the widely recognized symbol—“The Arch”—of St. Louis, Missouri, and the official centerpiece of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, “Gateway to the West,” administered by the National Park Service.

Its location was the jumping-off point at the opening of the 19th century for exploration of the nation’s newly acquired Louisiana Purchase and further westward expansion of the North American continent—what would come to be known as the country’s “manifest destiny” to occupy all the land between the oceans.

Today, more than a million visitors ride to the top of the Arch each year; since its opening in 1967, more than 25 million visitors have taken the tram up to the 630-foot-high top.

A monument to the nation’s history of expansion and exploration, and its link to where two of the nation’s largest rivers merge, would seem natural. Yet as natural as it seems, it still took more than three decades from the time it was first proposed until its public opening in June of 1967.

Those years were taken up with selecting a site, cleaning up the riverfront, removing buildings and utility lines, securing local approvals, adjudicating lawsuits, raising funds from government and private sources, and winning presidential and congressional approval. The shifting of priorities during World War II also contributed to the long timeline.

The formal beginnings of establishing the Arch, its grounds, and museum date to 1935, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave the Department of the Interior power to take land by eminent domain.

Yet in reality, the project began in 1933 with a group of civic-minded St. Louisans, known as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association (JNEMA) and led by Luther Ely Smith, an attorney who had adopted St. Louis as his hometown.

Build the Arch,

But Will They Come?

Getting the process started was a multidecade battle for those who were passionate about the project. The first issue was the site itself; it was in grave disrepair and acquiring it would require legal assistance to ensure the completion of the future Arch. The next hurdle would be the federal approval process for national monuments and memorials.

The President of the United States has the authority and power through the Antiquities Act of 1906 to establish national monuments, but Congress is the authority on national memorials. This would prove a sticking point that would embattle the JNEMA and Smith for years as they worked through many iterations of legislative bills in Congress.

But Luther Ely Smith was determined. He diligently gathered a group of prominent civic-minded citizens in St. Louis to work on ridding the riverfront of old buildings and railroad yard debris and establishing an open-air park that would cement St. Louis’s place in history as the “Gateway to the West.”

Smith had been inspired by his work on the federal commission that established the George Rogers Clark Memorial in Vincennes, Indiana. Smith’s idea was not an epiphany; for several years, others had previously attempted to construct a memorial, but the ideas never gained momentum.

By late 1933, Smith pitched his idea to city leaders, and within six months a state charter granted the JNEMA nonprofit status. Smith had a number of civic allies (likely garnered through his previous civic volunteer work) to help gain support for this idea, which aided in persuading the city to move forward.

The JNEMA’s goals were three-fold: to revitalize a blighted riverfront district; to help put Americans to work during the Great Depression; and to create a landmark that signified the ideals of opportunity and westward expansion.

This further perpetuated the American fascination with the West.

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner had noted that in 1890 the U.S. Census Bureau proclaimed no remaining frontier “line” in existence in the United States—thus essentially declaring the United States fully occupied and the cycle by which settlers invaded, migrated, farmed, and produced was no longer available or truly viable. If the frontier was closed, then a memorial commemorating it seemed most logical at the time.

Cutting Through Red Tape;

Seeking Approvals, Funds

The National Park Service set the memorial’s official “established date” as December 21, 1935, done under the Historic Sites Act—also passed in 1935—allowing for the preservation of historic American sites, buildings, and objects.

However, it would be another 30 years before the actual grounds and structure opened to the public. As Smith and others began their work, they quickly encountered several obstacles. The first was establishing a relationship with not only local lawmakers, but also the federal government. Memorial supporters had to sell the idea of land acquisition so that memorial work could commence.

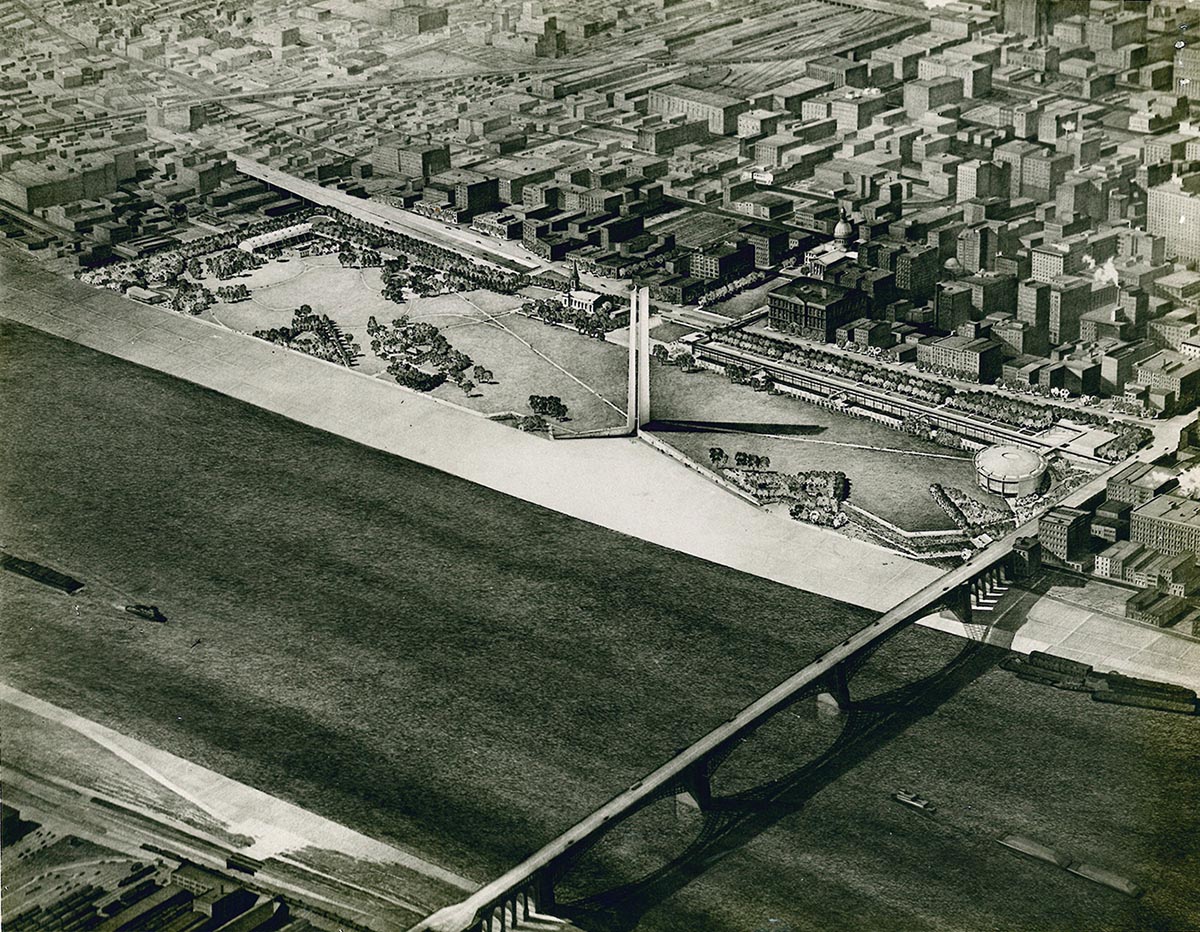

In 1936, the commission identified 82.5 acres of land in downtown St. Louis. By today's standards, it might be viewed as prime real estate, but in the 1930s it was an area that had been deemed blighted and the process of eminent domain would play a role toward land acquisition. The commission saw the land as valuable real estate due to its location near the historic city courthouse and along the Mississippi's riverfront.

Specifically, the commission targeted and designated 40 city blocks and 4,000 feet of riverfront space, or three-quarters of a mile, for the site. Its original proposal noted the boundaries for the project, defined the area’s historical significance (a westward expansion focus), and planned for a national architectural design competition to select a memorial design.

At the time, estimated costs for acquiring the land, developing, and planning of the project were around $30 million; according to the National Park Service, the total cost of building the Arch itself was $13 million.

St. Louis voters approved a bond proposal to help acquire funding; however, early litigation threatened to thwart the entire project. Supporters were vocal on both sides of the issue. Political pressure applied at the federal level prompted Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 7253, which allowed the Department of the Interior, the National Park Service’s parent agency, to acquire the land through the use of eminent domain. Not surprisingly, this led to more litigation.

Litigation Helps Clear

The Riverfront Site

Among the records at the National Archives in Kansas City, National Park Service correspondence files reference two court cases that relate to the land acquisition process.

The first, filed in 1937, is United States of America v. Certain Land in the City of St. Louis, State of Missouri (known as City Block 2 and Valentin Warehouse Company a Corporate, et al.). Essentially under the provision of eminent domain, the U.S. government sought to acquire land through condemnation. The land owners fought back, noting that their land parcels were valuable and wanted fair monetary compensation.

Based upon ownership, three parcels made up the land. The Valentine Warehouse Company, an entity that stored food goods including sugar, owned one parcel. One of their primary business contracts was the C&H Sugar Co., and they used river access frequently to offload product as it came in through the Mississippi River. The government offered $115,000 in land compensation. The second parcel belonged to Mangelsdorf & Bros., Inc., a wholesale seed company with a compensation offer of $93,200.

The third (and smallest) parcel belonged to MO Valley Trust Co., which was offered $1,400 in land value compensation. Because numerous motions extended the court case for many years and it occurred while the United States was involved in World War II, the occupants eventually wound up paying rent to the federal government before actually vacating the land in the mid-1940s. As with any landlord, the rent increased annually, according to court documents.

During the entire process, the defendants continued with filings in the case through the early 1950s, at which point progress had been made toward selecting a design and moving ahead with construction of the memorial.

The second court case, filed in 1938, is United States of America v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, St. Louis Refrigerating and Cold Storage, Union Electric Company of Missouri, and Laclede Glass, Light Company. This case, brought by the federal government, was the catalyst in pressuring the utility companies to remove their underground gas, electricity, telephone conduit, and pipelines from the JNEM site. The City of St. Louis had already vacated the land; through court proceedings, the federal government stripped the utility companies of land access rights.

Settled within a few years, this case eventually relocated all the buried lines and cables. The utility companies and land owners were not the only entities upset at the proposed memorial location, however. This outcome now forced the Terminal Railroad Association to move elevated railroad track lines and structures as a part of land acquisition.

Truman Links Arch

To Thomas Jefferson

By 1950, the previous tenants vacated the property, and President Harry S. Truman dedicated the site. In his remarks, he expressed a great deal of reverence for Thomas Jefferson, particularly the third President’s foreign policy work. Truman noted: “Today, our foreign policy is that of one of the strongest nations in the world. But the future welfare of our country still depends upon our foreign policy just as it did in Jefferson’s time.”

Truman said that since Jefferson’s time, the world had shrunk and totalitarian tyrannies have sprung up around the world, threatening free governments everywhere. He advocated a strong international leadership role for the United States, citing the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Treaty as examples.

Truman’s remarks came at a turning point for the project.

America’s involvement in World War II had put the Arch on the back burner, idling it for more than six years. Now, with the war over, and with the land now in public hands, the hard work of establishing appropriations funds for developing the memorial began.

In a February 1951 letter to Senator Joseph O’Mahoney of Wyoming, chairman of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, supporters stated that not only did the Department of the Interior “recommend enactment of the proposed legislation” and subsequent federal appropriations money, but they also urged the committee to consider assisting with the aforementioned removal of the elevated train tracks owned by the Terminal Railroad Association.

Eventually a memorandum of understanding among all involved parties allowed for the tracks to be removed. However, much hand-wringing and concern was continuously communicated in writing to elected officials and supporters about various aspects of the project.

In addition, throughout the National Park Service records at the National Archives in Kansas City, several documents exist that served as talking points and memos used by the JNEMA. One document titled “Draft of Talk to be Illustrated by Slides” highlights the bureaucratic process behind the Historic Sites Acts and the steps taken to establish the memorial.

Another document crafted was a five-page letter to prospective donors to help establish and fund the JNEMA’s Architectural Memorial Fund. The fundraising goal at the time was $225,000 to help offset the costs of the architectural contest to select a designer. The Association had no problem with meeting its fundraising goal as Smith himself personally gave $40,000.

A Multi-Talented Team Wins

Competition to Design Arch

Earlier during World War II, Smith had been asked [publically] what he thought the memorial should look like, what his vision of the site was. “There should be a central figure, a shaft, a building, an arch, or something which would symbolize American culture and civilization,” he replied.

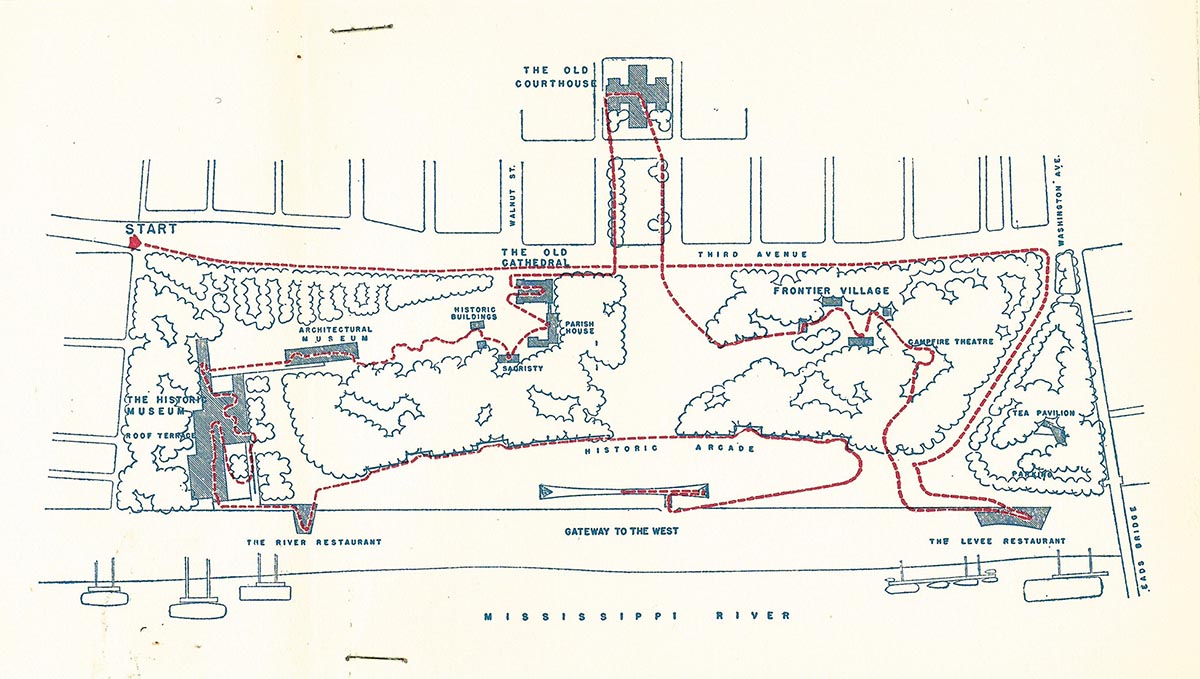

But establishing the memorial was harder than both the association and NPS had originally conceived. From the talking points used with a variety of groups, they noted that “in the maze and complexities of the various agencies interested, we found as many ideas as there were individuals. It was conceived that the memorial feature could be a monument, sculpturing, buildings, landscaping or a combination of all.”

First, the association solicited design ideas from the public through a nationwide competition in 1947; no federal money was used for this part of the process. They received more than 170 design plans, selecting five for the final design competition.

The five final teams consisted of professional architects. In each design submission packet, the teams included not only preliminary design details but also information about those on the design team, including birth details, marriage and family status, education, professional associations, teaching, awards, and military service. Additional information included the architect’s previous work projects.

The winning team of the design competition was led by Finnish-born architect Eero Saarinen, who was a partner in his father’s architectural firm Saarinen, Saarinen, and Associates, based near Detroit, Michigan. The Saarinen team included five individuals—four men and one woman—the only group among the finalists to include a woman.

Lily Swann Saarinen, a sculptress and a writer, was also the wife of Eero Saarinen. The Saarinens were no strangers to competition. Eero had designed the famous “Tulip Chair” with Charles Eames; Lily Swann was also a professional skier, having been a reserve competitor on the U.S. Olympic team in 1936.

All combined, the team had an impressive list of experience in education and projects: two were architects, one was a landscape architect, and another was an interior designer. Their credentials included three who had attended either Harvard or Yale and another who had studied at the Pennsylvania School of Fine Arts. Their clients included General Motors, Lincoln Motor Company, IBM Corporation, Detroit Civic Center, Antioch College, Drake University, Stephens College, Rock Island Railroad, and numerous government projects at the federal and local levels.

Professional Historians

Help in Museum Phase

The Saarinen team won a $40,000 cash prize for its Gateway Arch design in 1948—approximately half a million dollars in 2016 currency. Smith noted in a solicitation letter to the supporters of the memorial project that “the work of the winner of this contest will stand down the ages with the notable and beautiful buildings of civilization—with the Acropolis, with the forum of Rome.”

The museum phase of the JNEM served as the final piece of the project. The goals included highlighting the plight of the average settler journeying across America as well as the experiences of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s expedition west, thus translating the Westward Movement.

Professional historians were asked to aid in this effort. National Park Service records contain details about the actual museum phase and a copy of the proposed exhibit script, including the case labels and key statements for each aspect of the exhibit. Portions of the original exhibit text were reflective of their time, as one label noted:

“Before the Great Plains and the Rockies could be made safe for the cattlemen and the miner, the hostile Indians had to be subdued in a series of campaigns that kept the Army in the field for over thirty years.”

In 1948, Smith wrote to Saarinen:

“It was your design, your marvelous conception, your brilliant forecast into the future, that has made the realization of the dream possible— a dream that you and the wonderful genius at your command and the able assistance of your associates are going to achieve far beyond the remotest possibility that we had dared visualize in the beginning.”

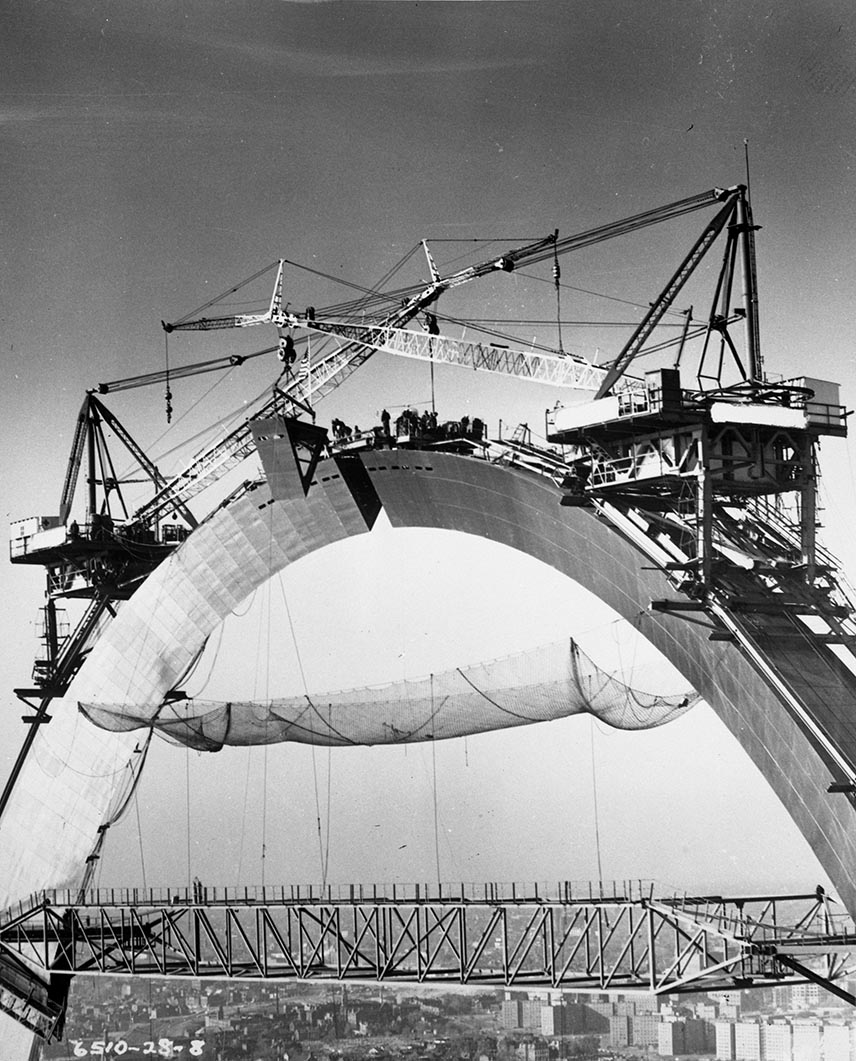

The Arch fulfilled Smith’s dream of a memorial, but he did not live to see it. He died dying in 1951, nearly a decade and a half before its completion. Saarinen would go on to design Dulles International Airport near Washington, DC, and the Trans World Airlines (TWA) Flight Center at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, both of which showcase similar design curves as the Arch, the catenary or U-shape.

Saarinen also died before project completion, in 1961, of a brain tumor. Saarinen’s business partners, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, oversaw completion of the Arch after his death. Formal construction on the Arch itself began in 1963 and was completed in 1965.

In late 1967, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower toured the Arch on a visit to St. Louis. He called it a “remarkable experience” and found the technological aspects intriguing. Dick Bowser, the designer of the tram system installed in the Arch, toured with Eisenhower. Bowser noted in his account of the visit that the former President kept saying things like “this is very unusual” or “this is very unique” as Eisenhower had opted to take a ride to the top to view the city from above.

Epilogue

Today the Arch continues to signify westward expansion and more recently downtown revitalization.

In late 2015, the city of St. Louis celebrated the 50th anniversary of the memorial with a renovation of the grounds in a public-private partnership with the National Park Service. The highlight of the two-year renovation project will include the “park over the highway,” a new green space area located atop U.S. Interstate 44. It will allow visitors to walk from the riverfront to downtown—just as the early residents of St. Louis did when it was the starting point for the opening of the American West two centuries ago.

Kimberlee N. Ried, a public programs specialist for the National Archives’ National Education and Public Programs Team, has been with the agency since 2003. She holds master’s degrees in library science from Emporia State University and communications from Park University. Her previous topic contributions to Prologue include WPA-era artwork and the historic renovation/adaptive reuse of the Kansas City regional archival facility.

To learn more about . . .

- The National Park Service through NARA-held records, go to www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/079.html.

- President Thomas Jefferson’s efforts to win funding for the Lewis and Clark expedition to explore Louisiana Territory, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/jefferson-message.html.

- How the Homestead Act speeded westward expansion, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/winter/homestead.pdf.

Note on Sources

Records used for this article come from the U.S. District Courts and the National Park Service files found at the National Archives in Kansas City. This includes Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, Region II (Midwest Region) Omaha, NE, National Parks and Monuments Central Classified Files, 1936–1952, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial.

Some of the correspondence found in the regional files are duplication copies with the originals retained by the headquarters of the National Park Service. Those files are located at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Other National Archives at Kansas City holdings included Record Group 21, Records of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern (St. Louis) Division of the Eastern District of Missouri, Civil Case Files, 1938–1992, and Equity and Law Case Files, 1857–1938.

Other National Archives records include materials from the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri, specifically the President’s Personal File and the Official Files.

Additional sources include information from the administrative history of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and The Museum Gazette, “Luther Ely Smith: Founder of a Memorial,” March 2001, published by the National Park Service and available online at: www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/upload/luther_ely_smith.pdf and www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/upload/119.00.prepark-2.pdf. Also, the interview transcript completed by Archives of American Art was helpful in learning more about artist Lily Swann: www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lilian-swann-saarinen-12593. Other sources include The Significance of the Frontier in American History by Frederick Jackson Turner and the September 2015 issue of Midwest Traveler, published by the American Automobile Association. Thank you to Jennifer Clark at the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and to Brian Finch and Taka Yanagimoto at the St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame and Museum for their help with securing additional images of the Arch.

Special thanks to my NARA colleagues Christopher Zarr and Sam Rushay for their professional editing assistance. Also thank you to Jim Armistead at the Truman Library; and Tim Rives and Pam Sanfilippo at the Eisenhower Library for their attention to detail and willingness to accommodate my questions and requests. In addition, thank you to Greg Bognich, Joyce Burner, Lori Cox-Paul, and Stephen Spence for their helpfulness with my multiple requests for records to review. Last and never least, thank you to my husband, Erik Bergrud, for his insistence upon purchasing our membership to the American Automobile Association; its brief article published in 2015, titled “The Arch at 50,” inspired this research and article.