The CCC Indian Division

Summer 2016, Vol. 48, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Cody White

"The Crow Indian has a long established custom of going into the mountains during the summer months to hunt, fish, pick berries, and practice many of their sports and native arts and crafts. Since the I.E.C.W. has come into the Indian's life, his trips to the mountains are just as numerous but their nature entirely different. He now goes to build fences, cabins, look-out towers, truck and pack trails and develop springs."1

So wrote Running Hawk in Indians at Work, a Bureau of Indian Affairs publication, back in 1935 about the Indian Emergency Conservation Work (IECW) program. The IECW, later known as the Civilian Conservation Corps Indian Division (CCC-ID), was largely overshadowed by the much larger regular CCC but was still a landmark program on federally recognized reservations during the 1930s. It employed thousands of Native Americans and brought material aid and conservation efforts to their considerable land resources.

The story is now as legendary in American history as the President who implemented it—facing widespread unemployment and economic unrest, newly elected President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt, in his remarkable first 100 days in office, ushered in a flurry of new legislation aimed at helping the beleaguered nation.

Arguably the most famous was the Civilian Conservation Corps, or Emergency Conservation Work as it was formally known until 1937. Today the National Archives assists researchers looking into their ancestors' roles in the CCC as one of the nearly 3 million men who helped preserve and manage the nation's natural resources.

Genealogists researching their Native American roots may overlook the people and activities of the separate Indian work programs. Shortly after the March 1933 passage of the ECW legislation, Congress passed a similar act authorizing the IECW program. The records of those Native American enrollees, what they worked on and how they lived, can also be found in the holdings of the National Archives.

People researching CCC-ID records within Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), should be aware of some peculiarities of the records that complicate their search. Generally a person beginning to look into an individual's CCC service will first contact the National Archives at St. Louis for a copy of the CCC personnel folder, which lays out the basic facts of the enrollee's service.

Since the CCC-ID was a separate program that was largely administered at the tribal level, such personnel records were never consolidated nationwide, and whatever was saved can now only be found piecemeal in the records of the various BIA agencies. Therefore it is essential to know the tribal affiliation of the enrollee or the reservation where the work took place before embarking on any research.

Researchers will discover a lack of uniformity in what was saved, at the general CCC-ID level and from agency to agency. For example, while the Crow Agency of Montana saved only project reports detailing costs with no information on individuals, the Northern Cheyenne agency, a scant 50 miles away, saved detailed documentation on all aspects of enrollee life. Further complicating research are the differences in how those records were saved. In some cases, CCC-ID records are given their own specific title, and in others they are filed away in large correspondence series under a decimal code heading (often 900 Industries and Employment). For all of these reasons, it is always advisable to contact an archivist beforehand for assistance in navigating the files and to learn what there is for a particular tribe or reservation. This article concerns only BIA records held in the National Archives at Denver, but similar records, if not comparably organized, can be found at additional National Archives facilities.

How They Joined

With the ravages of the Great Depression hitting Native Americans particularly hard, BIA officials leaned on the Roosevelt administration in the hopes that the newly created Emergency Conservation Work program could be used for conservation efforts on the massive reservations throughout the west.

Roosevelt agreed, and the IECW was created as a separate organization from the larger ECW program, which allowed for many differences in enrollment and camp structure.

Tribal leaders, not the Department of Labor, would select the enrollees and projects, with technical assistance provided by the BIA. Only members from a particular reservation could apply to work on said reservation unless approved by tribal council. At the Flathead Agency, for example, applications from the Turtle Mountain Chippewa in North Dakota were forwarded ostensibly to help with a manpower shortage on the Flathead Indian Reservation.

Most agencies represented in records at the National Archives at Denver did not save the applications for enrollment, so these Flathead records offer a rare glimpse into just how dire the circumstances were for many enrollees. Nineteen-year-old John James Allery, who made the trek west from North Dakota and reported for duty on the Flathead Indian Reservation in November 1933, is listed as having to support his parents and nine siblings.2

More commonly than applications, one will find physical examination results, which are simple one-page forms detailing the condition of the enrollees and giving such basic information as height and weight. This requirement, too, was fluid. The Santo Domingo Pueblo protested the examination, stating that tribal rules prohibited it, and so the physicals were waived.3

The CCC-ID also differed from the regular CCC in the ages of enrollees. While the regular CCC enrolled only those between 18 and 25 years old, the CCC-ID had no such restriction. In 1940 the approximate average age of the enrollees reported by the Northern Cheyenne Agency was 34,4 and records from the United Pueblos Agency show that in 1942 alone there were 172 enrollees over the age of 35, with three even being 75.5 While the higher age range may be partially explained by the growing manpower shortage following the country’s preparation and subsequent entry into World War II, it also highlights the flexibility tribes had in choosing the workers.

How They Worked

The projects completed by the CCC-ID were as diverse as the tribes that accomplished them. The building of dams, roads, trails, fences, wells, telephone lines, and sheds along with firefighting, working as hospital orderlies, and the growing of community gardens are all detailed in the records.

Many of the agencies created what are called narrative reports, which are periodic dispatches, often with photographs, that would detail the work done by the enrollees. While often not listing individual names, these reports are an invaluable resource in seeing exactly what was done and even serving to showcase camp eccentricities, such as the pet eagles kept at the Uintah and Ouray Agency Hidden Camp in 1941.

Because the CCC-ID had no set enrollment periods, these narrative reports were submitted on a quarterly per year basis. Similar to the narrative reports were inspection reports, which were often compiled and formatted in a similar way and featured much of the same content—project statuses and camp conditions along with photographic documentation.

Aside from the internal narrative and inspection reports, the BIA publicized the CCC-ID program and its accomplishments through various public outlets. Indians at Work was first published by the BIA in 1933 solely to highlight CCC-ID accomplishments nationwide. While it would be expanded to include all aspects of BIA work before shuttering in 1945, it still remained a valuable resource for chronicling the work done by enrollees on various reservations. Issues can be found within the correspondence files of many BIA agencies.

Some tribes, such as the Shoshone with the Tattler and the Blackfeet with the Tom Tom Echoes, opted to publish their own newsletters, which featured a great deal of anecdotal history along with jokes, stories, and even drawings from individual enrollees. One such example from the Tattler is the "Coments [sic] from Camps," a news section that lets us know that in 1935 "[t]he question as to just who is the main crewboss was settled in the Trout Creek camp on the evening of November 21st. 'Jim Corbett' Hamilton kayoed 'John Sullivan' Hurtado in the first round."6 Copies of these newsletters were sporadically saved by the agencies and, when present, are almost always found within the general correspondence series.

When it comes to individual work contributions within the CCC-ID, greater records were retained on the camp leaders, those in skilled positions who led the enrollees on the projects. For these persons, you may find work evaluations, individual pay stubs, leave requests, correspondence, and even fingerprint cards. Work-related documents for individual enrollees are typically only seen in two types: pay and accident records.

While mundane compared to the narrative reports, pay records can detail who was enrolled when, how much they were paid, and where those monies were sent. Unlike the regular CCC, where the enrollees were required to live in camp and received a flat $30.00 a month, CCC-ID enrollees could earn extra pay. They could receive $1.00 to $2.00 a day for use of their own horse7 and, in the absence of camps, $3.00 for room and $12.00 for board a month on top of the base $30.00 a month.1 These pay records are able to provide at the least a basic outline of an enrollee's service in the absence of enrollment applications.

Given the nature of the job and the relatively unskilled workforce, accidents were an inevitability, and the records bear this out. Many agencies' records include general reports with accident statistics and reports filled out for individual accidents. Both types of reports are usually organized by date rather than name but can provide an in-depth look at a particular enrollee.

How They Lived

Life for the CCC-ID enrollee was at times markedly different from a CCC enrollee. For the Native American enrollees, a work day was just that—there was no curfew, and they were free to leave camp. In many cases, there was not even a camp to stay at. If the project was close enough, enrollees traveled there from home each day and were compensated accordingly. In the CCC-ID, objections arose early on to large 200-man "quasi-military camps," which on the sparsely populated reservation lands were impractical anyway. Instead, when camps were necessary, the tribes set up different types of camps depending on the length of project, location, and available manpower.9

For some projects, the CCC-ID built small, permanent bunkhouses for single men. In other cases, family tents were erected so men could bring along their entire household. Photographs in narrative and inspection reports show these varied living conditions and provide a glimpse into the life of an enrollee.

The goals of the CCC-ID, as with the regular CCC, were not only to complete projects that could help preserve the land but also to endow the enrollees with skills to take forward in their lives. Education therefore features prominently in training materials, examination results, photographs, and at some agencies, films (a sign of the changing times in the 1930s).

For example, to cover the topic of stock feeding, the Northern Cheyenne Ashland camp planned to show the Swift and Company film Feeding the Nation, followed by the animated Tom & Jerry short Barnyard Bunk.10 Films were shown not just for their educational value. Over two months in 1935, a distributor from Salt Lake City screened a series of Hollywood films at the Uintah and Ouray Camp #1, and enrollees from the neighboring agency camps, some as far as 45 miles away, were invited to attend.11

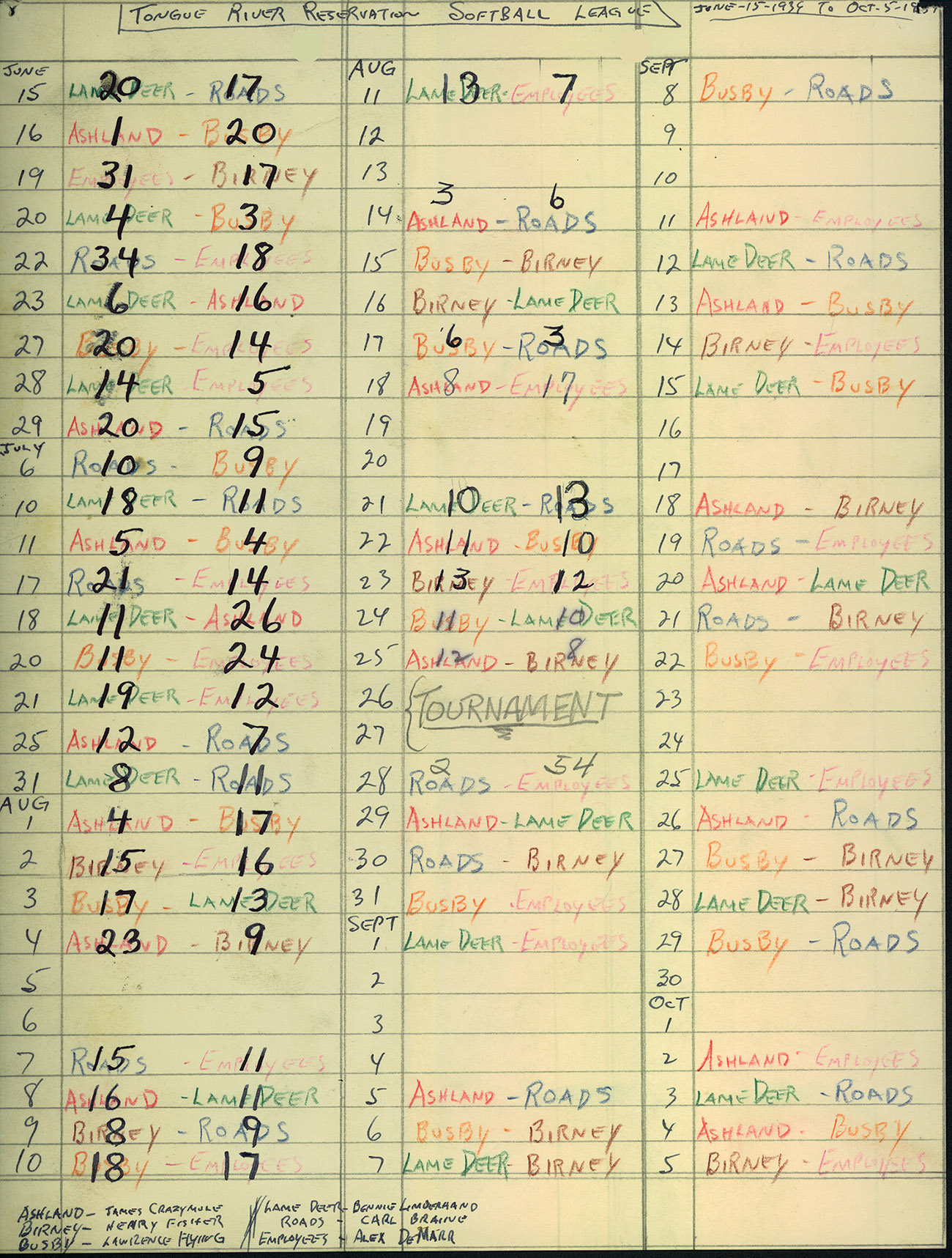

Sports were also an important part of the enrollees' free time. The Wind River Agency recorded basketball games held between camps during the winter, and the Northern Cheyenne camps played softball against each other and regular BIA employees. Though individual names are rarely found in these particular records, they do showcase the general activities of the enrollees at the time.

After the CCC-ID

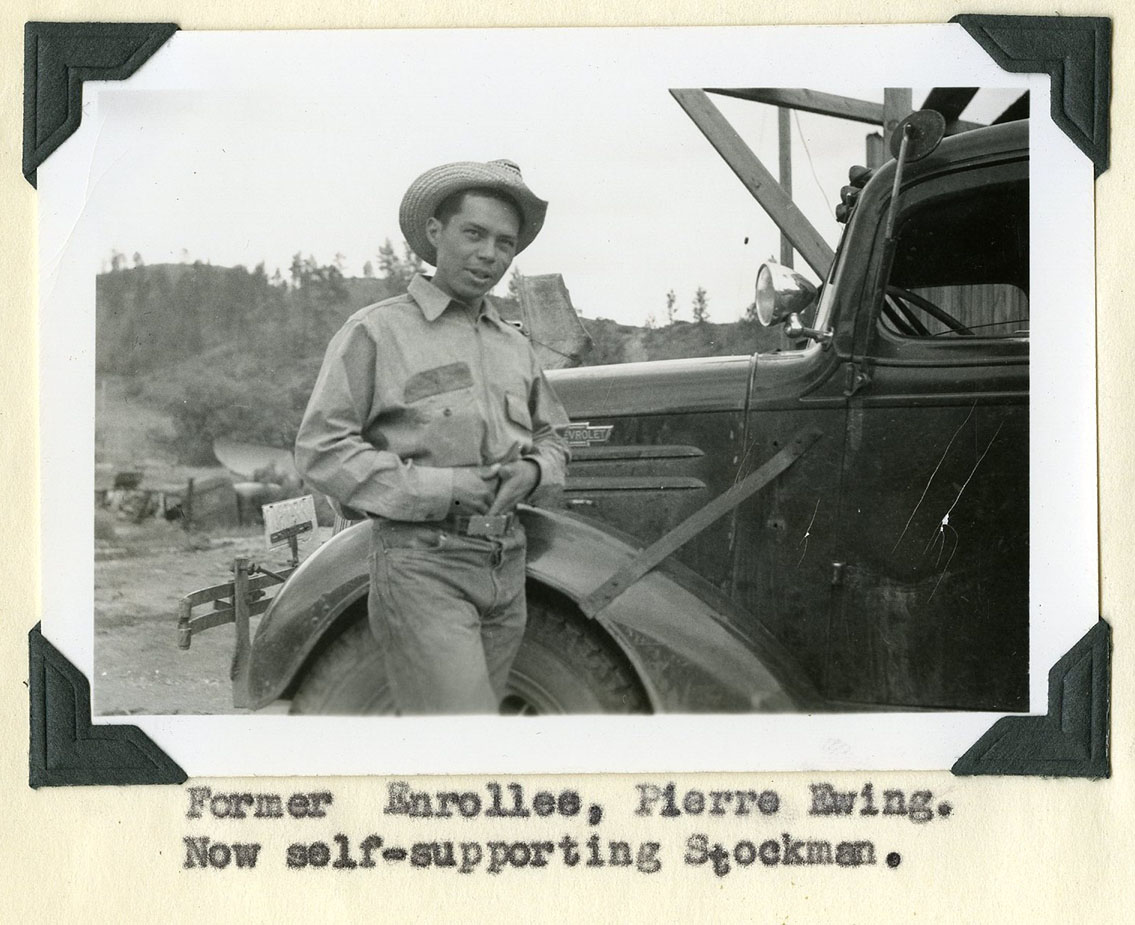

In some cases the historic record on an enrollee does not end with the conclusion of his CCC-ID service. Promoting the narrative of how beneficial the program was for the men, some agencies would highlight the successes of former enrollees in their reports. In particular, through the Northern Cheyenne Agency's 1941 narrative report on CCC-ID activities we learn that, after their service, Dave Robinson bought and operated his own stock truck, Pierre Ewing became a self-supporting stockman, and Ray Bolson moved to Kirkland, Washington, to become a welder at $1.62 an hour.12 Within the Uintah and Ouray Agency records one can find letters of recommendation written by BIA officials for former enrollees, offering yet another chronicle of an individual's service.

As with the regular CCC, World War II spelled the end for the CCC-ID, and the program was shuttered in 1942. Four days after the U.S. House of Representatives rejected funding the program for the 1943 fiscal year, the CCC-ID director directed all agencies to set aside funds to liquidate the CCC-ID and make every effort to absorb CCC-ID personnel into regular BIA employment if possible.13

While the camps were shuttered and the supplies parceled out to various federal agencies, many of the projects such as roads and dams can still be seen today. For the generation of Native Americans who weathered the Great Depression, the records of the CCC-ID found in National Archives facilities nationwide provide a glimpse into their life and work.

Cody White is an archivist with the National Archives at Denver. He holds a B.A. in history from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and an M.L.I.S. from the University of California-Los Angeles.

Notes

The records discussed all come from National Archives Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Additional background information on the CCC-ID not found with the agency records comes from Calvin W. Gower's "The CCC Indian Division; Aid for Depressed Americans, 1933–1942," Minnesota History 43 (Spring 1972): 3–13), and Roger Bromert's "The Sioux and the Indian-CCC," South Dakota History 8 (Fall 1978): 340–356.

1. Running Hawk, "I.E.C.W. on the Crow Reservation," Indians at Work, Oct. 1, 1935, p. 17; 661 Publicity Indians at Work; Box 244; General Correspondence Files, 1935–1952 (Entry 99); United Pueblos Agency; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group (RG) 75; National Archives at Denver (NAD).

2. John James Allery; ECW Applications for Enrollment; Box 1; Emergency Conservation Work Correspondence and Reports, 1930–1942 (8NS-075-96-369); Flathead Agency; RG 75; NAD.

3. Telegram, Assistant Commissioner Zimmerman to Commissioner Collier, July 15, 1937; 900.2 CCC-ID Enrollment; Box 261; General Correspondence Files 1935–1943 (Entry 99); United Pueblos Agency; RG 75; NAD.

4. O. H. Schmocker to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Oct. 4, 1940; 150 Inspections and Investigations of Visiting Officials; Box 2; Miscellaneous IECW and CCC-ID Reports, 1933–1942 (8NN-075-97-056); Northern Cheyenne Agency; RG 75; NAD.

5. S. D. Aberle to William H. Zeh, May 19, 1942, enclosure; 900.2 Industries and Employment Enrollment; Box 83; General Correspondence Files 1935–1943 (Entry 99); United Pueblos Agency; RG 75; NAD.

6. Tattler, Nov. 28, 1935, pg. 3; 011-A-1 Wyoming Indian (Tattler); Box 79; General Correspondence Files 1890–1960 (Entry 8); Wind River Agency; RG 75; NAD.

7. Roger Bromert, "The Sioux and the Indian-CCC," South Dakota History 8 (Fall 1978): 347.

8. Section II, p. 2; CCC-ID Handbook, August 1941 revision; Box 86; General Correspondence Files 1935–1943 (Entry 99); United Pueblos Agency; RG 75; NAD.

9. Bromert, "The Sioux and the Indian-CCC," p. 344.

10. Tentative Programs for Education Committee; Enrollee Program Amusements, Education, Etc.; Box 1; CCC-ID and IECW Project Records, 1933–1943 (8NS-075-97-054); Northern Cheyenne Agency; RG 75; NAD.

11. LaRose, Carnes, and Reed, Glenn, "Talkies at I.E.C.W. Camp #1"; 1003.3 Stories and Articles Regarding Enrollee Advancement; Box 14; Program Mission Files, 1935–1940 (8NN-075-92-042); Uintah and Ouray Agency; RG 75; NAD.

12. Charles H. Jennings to Tom C. White, Nov. 3, 1941, enclosure; Enrollee Program Tongue River; Box 1; CCC-ID and IECW Project Records, 1933–1943 (8NS-075-97-054); Northern Cheyenne Agency; RG 75; NAD.

13. D. E. Murphy to BIA Superintendent District Offices, June 9, 1942; Work Program July 1, 1941, to June 30, 1942, CCC-ID; Box 30; Health, Educational, and Welfare General Correspondence, 1908–1948 (8NS-075-96-445); Fort Belknap Agency; RG 75; NAD.