Transcription Tips

The National Archives is the nation’s record keeper. We preserve and provide access to the records of the U.S. government, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, as well as the records of ordinary citizens. Many of the documents at the National Archives are handwritten records such as letters, memos, and reports. Transcribing these primary sources helps us increase accessibility to historical records so that all of us can more easily read, search for, and use the information they contain.

By transcribing documents, you can help us unlock history and discover hidden aspects of records and the stories they contain.

Tips for reading Historic Documents

One hurdle to using historic records is how handwriting has changed over time — and that we don’t write in cursive as much as we used to. Here are some tips for reading handwritten documents.

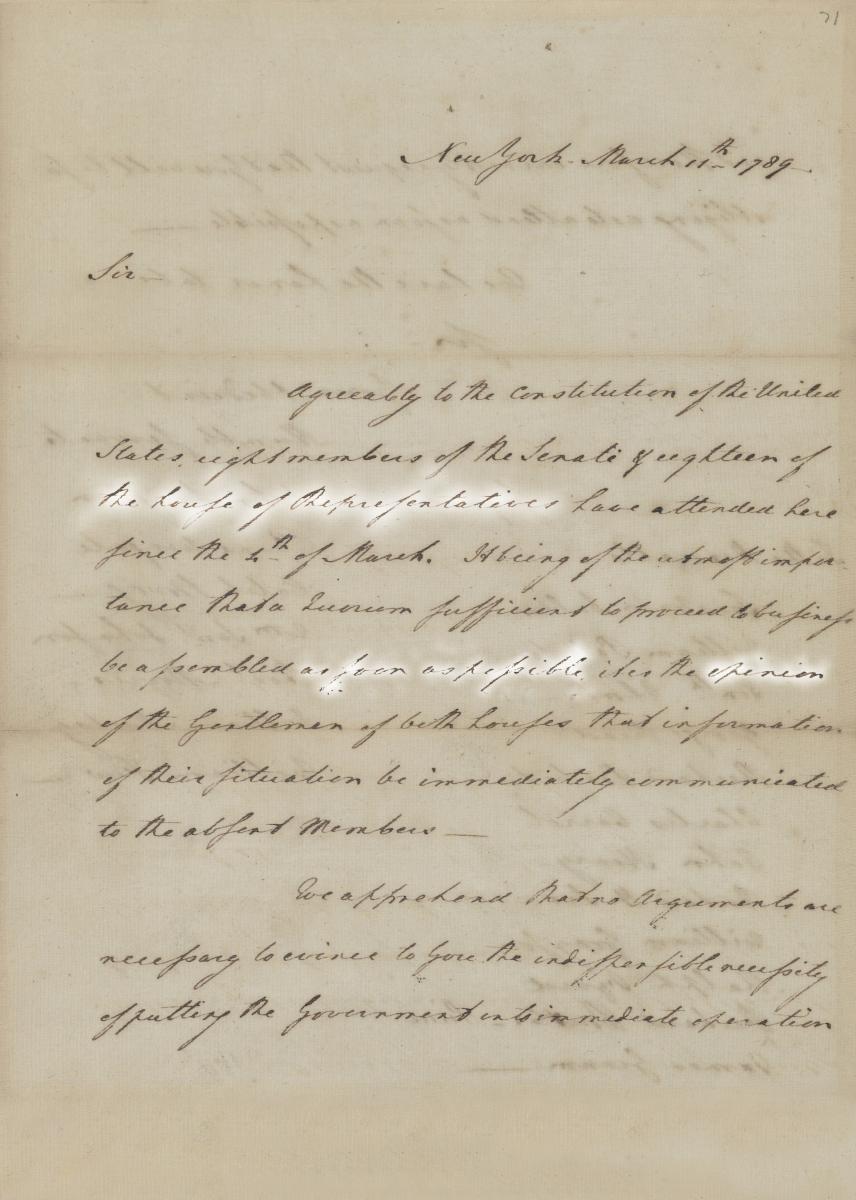

This Letter to Absent Senators from the Senate, dated 1789, has some great examples of letters that look weird to modern eyes, even if you’re used to reading cursive. In particular, the lowercase p and the lowercase long s may give readers some trouble. Let’s look at the whole first page. Agreeably to the Constitution of the United States, eight members of the Senate & eighteen of the houfe— Wait, what?

This letter that looks like a lowercase f is an s. You’ll see these in handwritten and printed documents into the early part of the nineteenth century. Since the two letters look very similar, try to use as many context clues as you can. Ask yourself if the words or phrases make more sense with an f or an s.

Since our options here are houfe of Reprefentatives or house of Representatives, it’s pretty clear which is correct.

Another letter that can cause trouble is that lowercase p. The style here is to have a much taller ascender, or vertical line, than we use on our letter p's nowadays. The round part (called the bowl) of the p may also be open at the bottom, making it look kind of like an h.

We can use context clues again with the p. Looking at the word Representatives above, we can see that the p does have the tall ascender and the open bowl. We can apply this to the rest of the document.

That second letter is a tall-ascender open-bowl p. The word is opinion.

Using our knowledge of the long s and the p, we can see that this is a common English phrase: as soon as possible.

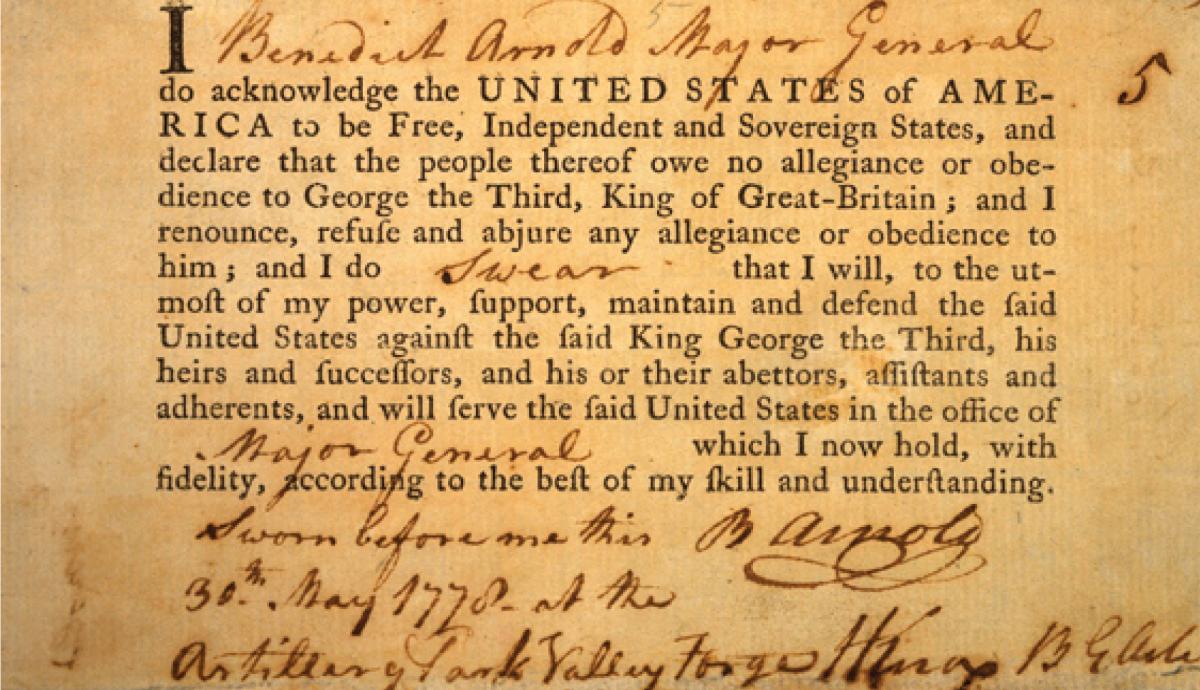

You may also come across the long s in typeset documents. For example, take a look at Benedict Arnold’s Oath of Allegiance:

You’ll see the typewritten long s numerous times within this interesting document. Using context clues as we read through the document, we can see that the letter that looks like a lowercase f is often an s. When you see this a document dated prior to the mid-19th century, be sure to transcribe it by using the “s” on your keyboard:

I Benedict Arnold Major General do acknowledge the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA to be Free, Independent and Sovereign States, and declare that the people thereof owe no allegiance or obedience to George the Third, King of Great-Britain; and I renounce, refuse and abjure any allegiance or obedience to him ; and I do [handwritten] Swear [end handwritten] that I will, to the utmost of my power, support, maintain and defend the said United States against the said King George the Third, his heirs and successors, and his or their abettors, assistants and adherents, and will serve the said United States in the office of Major General which I now hold, with fidelity, according to the best of my skill and understanding.

—Sworn before me this B Arnold 30 th Day of May 1778 – at the Artillery Park Valley Forge H Knox B G Artillery. View in National Archives Catalog

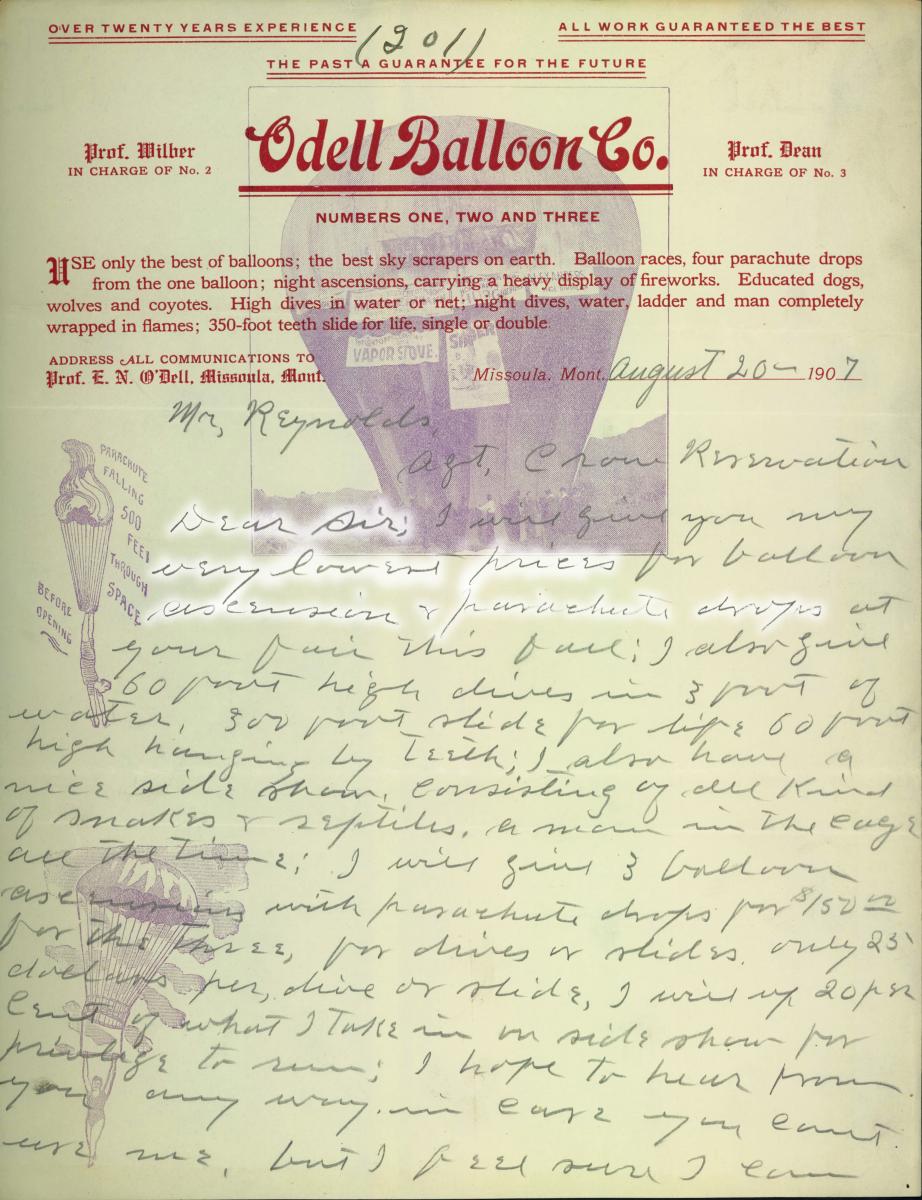

Take a look at “Dear Sir”. This is a really useful part of the letter to use to get your bearings, because “Dear Sir” is used in a lot of letters and doesn’t often have any spelling surprises.

We can see that the lowercase “e” in this word looks like a mirror-image “3”, sometimes called a “Greek e”. Knowing that the writer of this letter makes his “e”s like this can help us to puzzle out some words that might not be very clear. We can also see that the “a” in “dear” is open at the top. Maybe the writer leaves a lot of his round letters open.

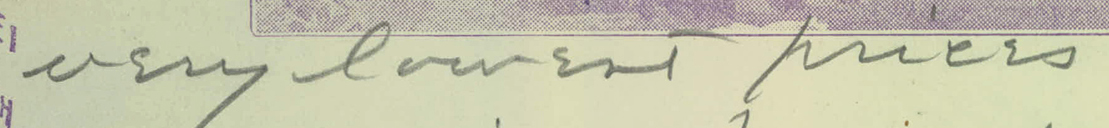

Here’s a phrase in the letter that might not be terribly clear:

Once we plug in “e” where those “Greek e”s are, it might be easier to see that the first word is “very”. The second word starts with a clear “l”, but the second letter could be a “u” or an “o” with an open top. “lowe*t” is more likely than “luwe*t”. What word fits there? That second-to-last letter is just an “s” that’s not connected at the bottom, making the second word in this phrase “lowest.”

How about the last word? If the second-to-last letter is an “e”, the third-to-last letter that looks like an “e” probably isn’t. What if it’s a “c” with a loop at the top? That first letter is a puzzler, though. In the “Letters to Absent Senators from the Senate” example, the “p” in that post is the same as the first letter in this word. The last word in this phrase is “prices”. Ready for another phrase?

With our knowledge of the open top “a”s and “o”s, the “Greek e”s, the loopy “c”s, and those pesky “p”s, we can see that this phrase is “ascensions and parachute drops”. Which is borne out by checking the red print in the letterhead: this company advertises “four parachute drops” and “night ascensions,” so it would make sense that those words are in this letter.

Tips for stamps and other unique features

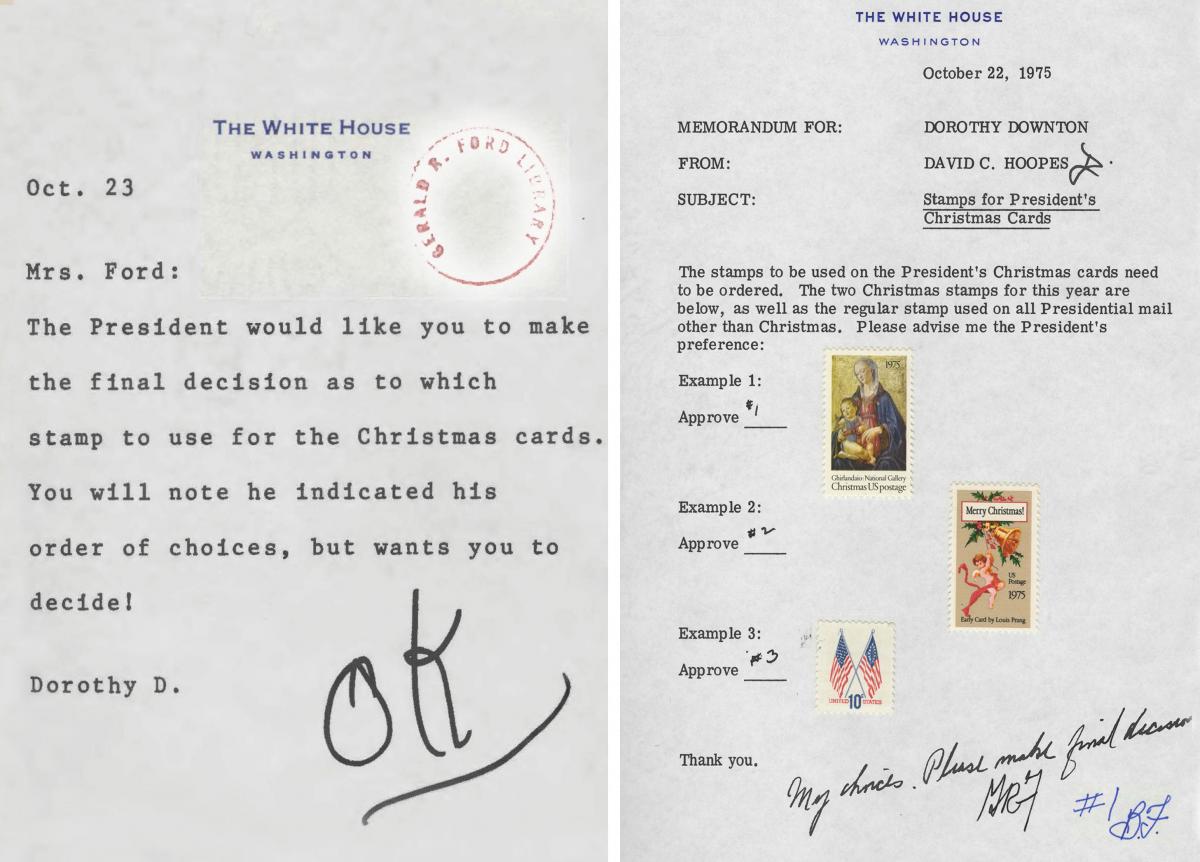

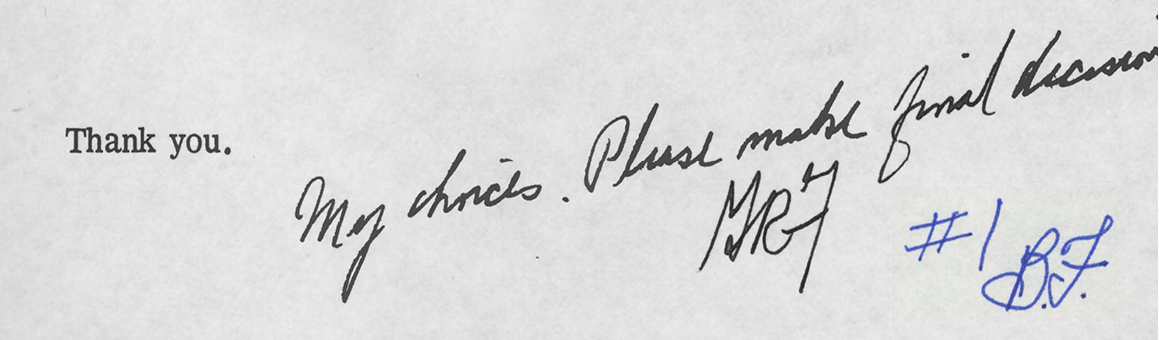

This Memorandum Regarding Stamps for President Ford’s Christmas Cards contains many unique features that may make transcribing challenging. In addition to the typewritten text, you’ll notice a stamp in the upper right hand corner. You’ll also notice a handwritten note at the end of the document.

Memorandum for Dorothy Downton from David Hoopes Regarding Stamps for President Ford's Christmas Cards. View in National Archives Catalog.

Tips for transcribing tables and charts

Transcribing Tables. Some records in the National Archives contain tables and charts that may be challenging to read and transcribe. This Slave Manifest for Brig Virginia of Baltimore contains a lot of details including names, dates and locations which are important to researchers.

Even though we see columns of hand-written information in this document, it’s not necessary to try to preserve those columns when transcribing. Transcribe the information in the table by writing out the row of text in one line. The goal of this transcription is to help understand the content in the document as well as help with search results. Notice the column headings are written out and the names of each passenger is transcribed on a separate line. Also notice that the transcription indicates crossed out text and a caret mark to indicate additional handwritten text:

MANIFEST of Negros, Mulattos, and ^free persons of Color, taken on board the Brig Virginia of Baltimore - whereof John Staples - is Master, burthen 23.9 — tons, to be transported to the Port of New Orleans - in the District of Mississippi — for the purpose of ^Residing in the city of New Orleans [crossed out: being sold or disposed of as Slaves or to be held to Service or Labour]

[column headings: Number of Entry. Names. Sex. Age. Height. Whether Negro, Mulatto, or person of Color. Owner or Shipper’s Name and Residence.]

- Lucy Boyer. Woman. 45. 5 1. light mulatto. Lucy Boyer for Herself & Children – Shipper

- Robert D. Smith. Male. 1.9 5 2. brown

- Caroline Boyer. Girl. 13. 4 10. lightish mulatto

- Emily Boyer. do. 9. 4 2. light mulatto

District of Baltimore, Port of Baltimore, the 1 day of November 1823

[illegible] I John Staples - Master of the Brig Virginia — do solemnly, sincerely, and truly swear each of us to the best of our ^my knowledge and belief, that the above described persons of Color have not been imported into the United States since the first day of January, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Eight; and that under the Laws of the State of Maryland, they are not held to Service or Labour, as Slaves and are entitled to freedom under these laws [crossed out text]— So Help me God.

Sworn to this 18 day of November 1823 before [illegible] McCulloch COLLECTOR

her mark [hand drawn X] Lucy Boyer

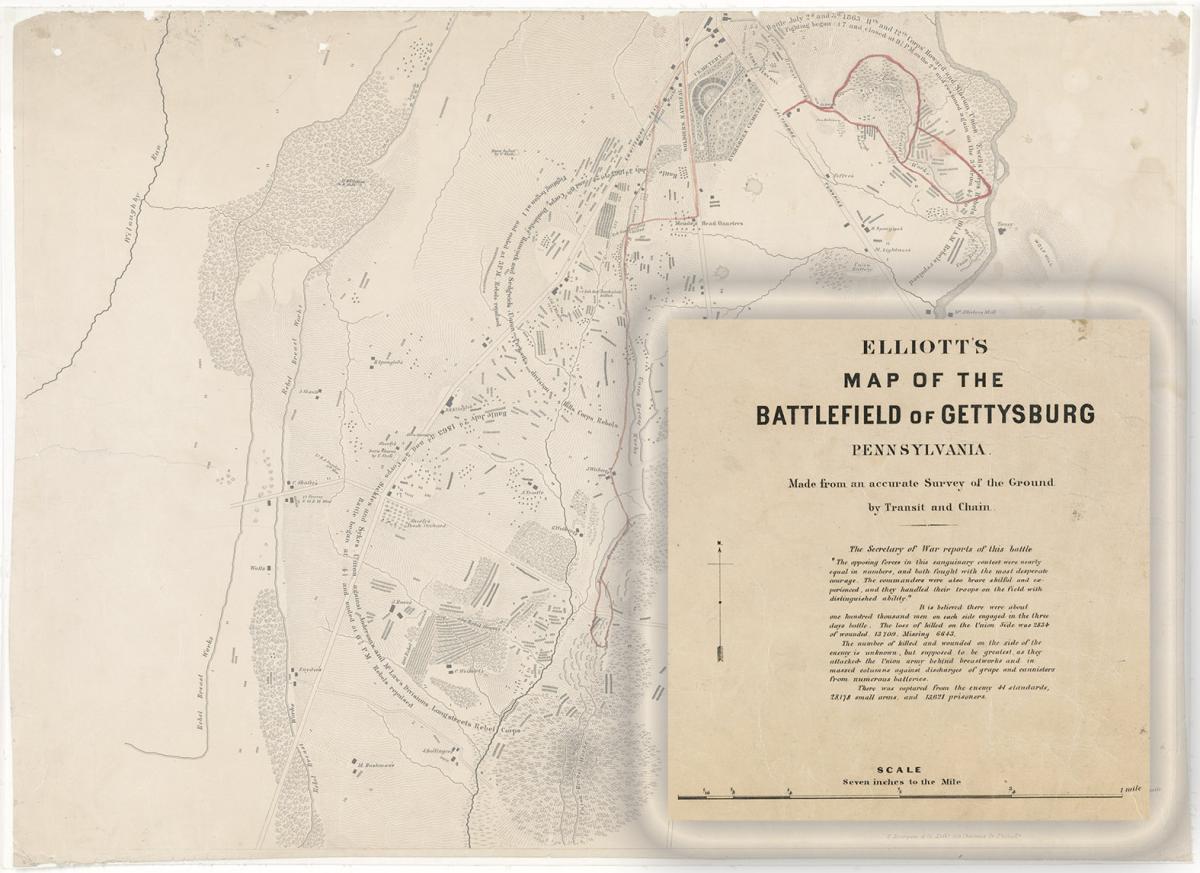

When transcribing maps, it might not be feasible to transcribe every street, river or landmark identified on the map. You can choose to identify those items in the [Tags] contribution area in order to make them searchable. Most maps, however, contains keys or legends with important information.

For example, the map below of the Battlefield of Gettysburg contains descriptive information about the map and the battle in the lower right corner. Zooming in on the text, we can now transcribe the map’s description. When transcribing, it is not necessary to preserve line breaks or hyphenated words in the text. Typing out sentences without line breaks will improve search results by allowing users to search for whole words or phrases in the document.

ELLIOTT’S MAP OF THE BATTLEFIELD OF GETTYSBURG PENNSYLVANIA (see below)

Made from an accurate Survey of the Ground by Transit and Chain

The Secretary of War reports of this battle “The opposing forces in the sanguinary contest were nearly equal in numbers, and both fought with the most desperate courage. The commanders were also brave skilful and experienced, and they handled their troops on the field with distinguished ability.” It is believed there were about one hundred thousand men on each side engaged in the three days battle. The loss of killed on the Union Side was 2834 of wounded, 13,709. Missing 6643. The number of killed and wounded on the side of the enemy is unknown, but supposed to be greatest, as they attacked the Union army behind breastworks and in massed columns against discharges of grape and cannisters from numerous batteries. There was captured from the enemy 41 standards, 28,178 small arms, and 13,621 prisoners.

More Maps and Reference Keys.

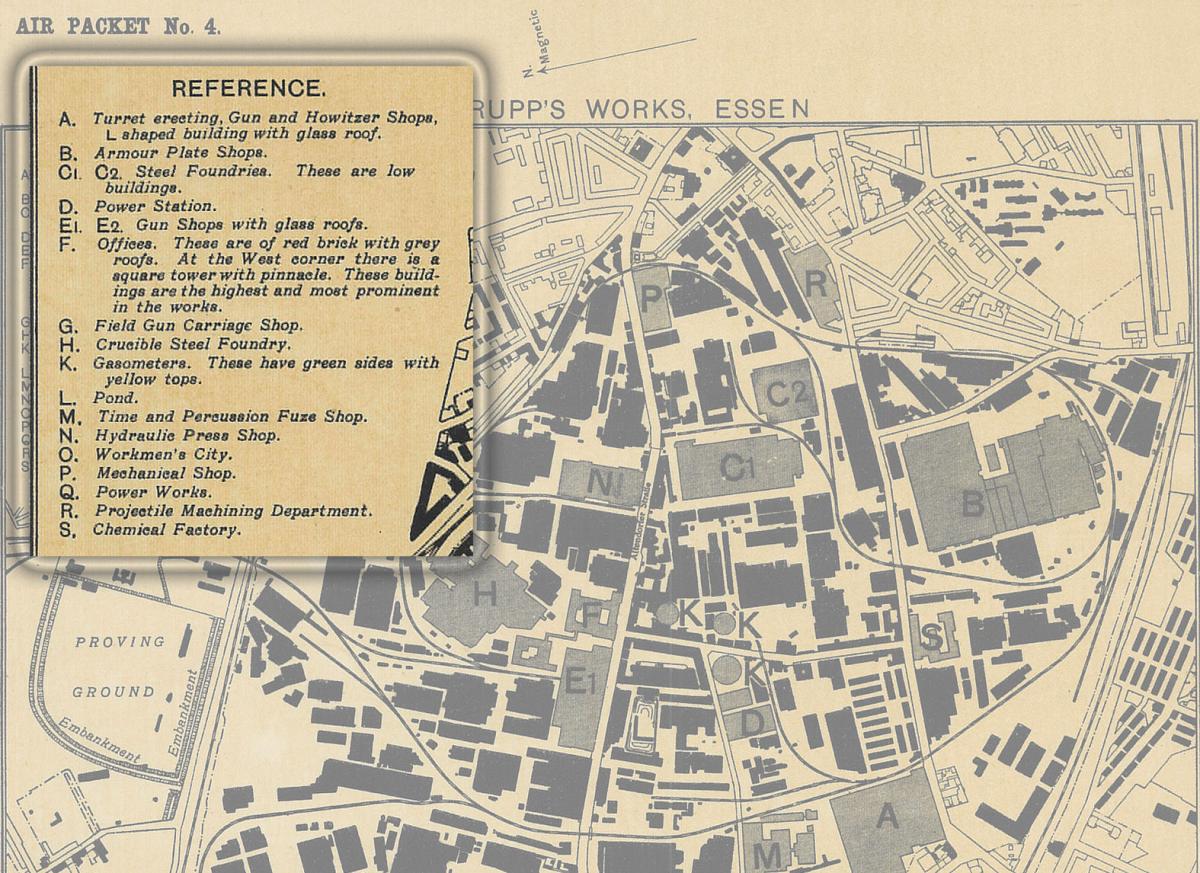

This World War I Air Map contains a reference key with important identifying information. The Reference key identifies portions of the map using letters.

A transcription of this portion of the map could look something like this:

Clues for understanding 18th and 19th Century documents

Be aware of contemporary spelling and abbreviations. The following list may help you decipher the words around the unusual word. Please transcribe the word as spelled or abbreviated in the document, however — do not correct it. If you wish, you can include correct spellings or significant un-abbreviated words in brackets following the word or abbreviation or in the [Tag] field.