A TOP SECRET Exhibit Previews the National Archives Experience

Fall 2003, Vol. 35, No. 3

By Bruce I. Bustard

Have you ever wanted to page through documents that were once secret? Would you like to explore stories of espionage missions, coded messages, wonder weapons, and war plans that were once limited to only a few officials with security clearances?

If so, then you won't want to miss "Top Secret," a computer interactive inside the new Public Vaults of the National Archives, a part of the National Archives Experience that will open in the fall of 2004.

Each year the National Archives declassifies hundreds of thousands of pages of documents. Some are made public through systematic reviews of large bodies of records; others become available because of individual researcher requests for declassification under laws such as the Freedom of Information Act. The National Archives also holds many older documents that, although they pre-date the formal document classification system that has been used by the federal government since the 1930s, were once shrouded in secrecy.

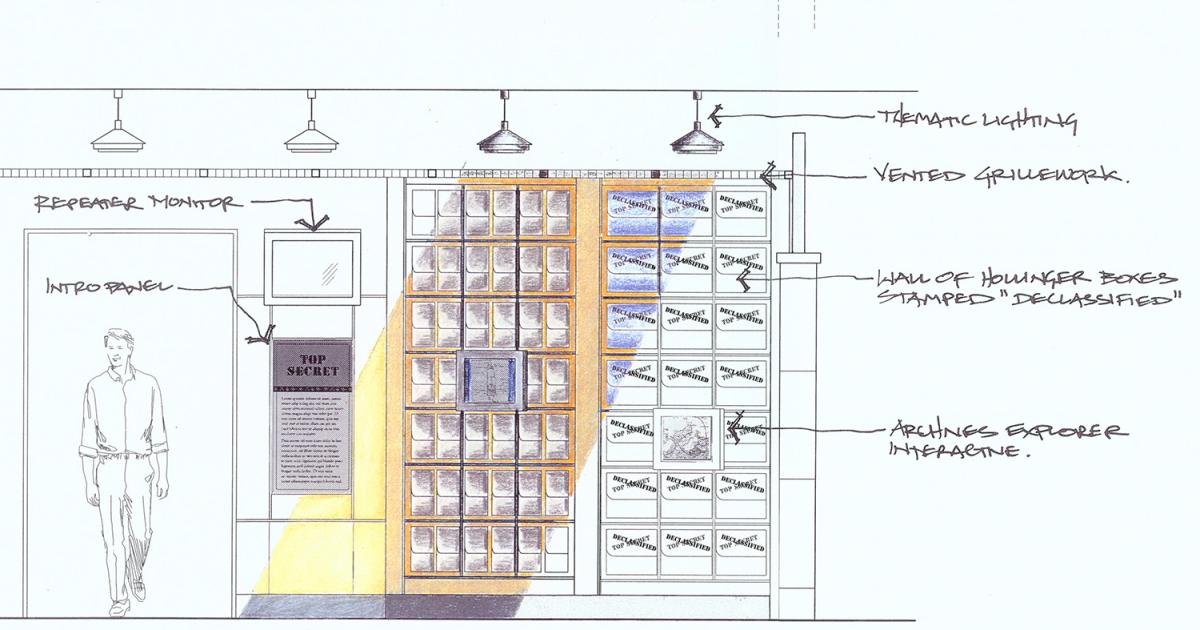

Many of these documents are well known to scholars, but students and the general public have seldom had the opportunity to peruse them. Soon, visitors to the Public Vaults and "Top Secret" will use a novel technological innovation, "The Archives Explorer," to inspect formerly secret documents, translate codes, highlight interesting stories, view documents in context, and see them come to life.

In addition, through the National Archives Experience web site, "Top Secret" will become a powerful teaching tool, where whole classrooms can explore in cyberspace this primary source material with students across the aisle or around the globe.

The inspiration for "Top Secret" and other interactive units in the Public Vaults sprang from two questions considered by the NARA team planning the National Archives Experience:

- How can we make National Archives documents and parts of those documents accessible and understandable to our visitors?

- How can we replicate the thrill and sense of discovery researchers feel when they come to our research rooms and open boxes containing formerly classified materials from the National Archives?

One answer to these questions was "The Archives Explorer." Physically, the Explorer has been likened to "a plasma screen on handle bars." It is a monitor that will move across the face of specially sensitized archival boxes. As the monitor passes over a box, it will "open," and its contents will be revealed. In "Top Secret," for example, a visitor might pause over a box labeled "The Zimmerman Telegram—A Code That Meant War." Opening this box, he or she will see a reproduction of a coded telegram sent from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to the Mexican government in 1917.

A first level will reveal the untranslated telegram, appearing as a series of seemingly undecipherable numbers. One set of numbers, 36477, will be highlighted. Another screen will show a reproduction of a document breaking the code, revealing that 36477 stood for "Texas." A third screen will display the complete translation of the entire telegram, highlighting the sentence offering to help Mexico regain New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona from the United States as a reward for supporting Germany in a war with the United States. The experience would conclude with an explanation of how, when the original translated Zimmerman Telegram was released, its content so angered the American people that public sentiment shifted decisively in support of America entering World War I on the side of the Allies.

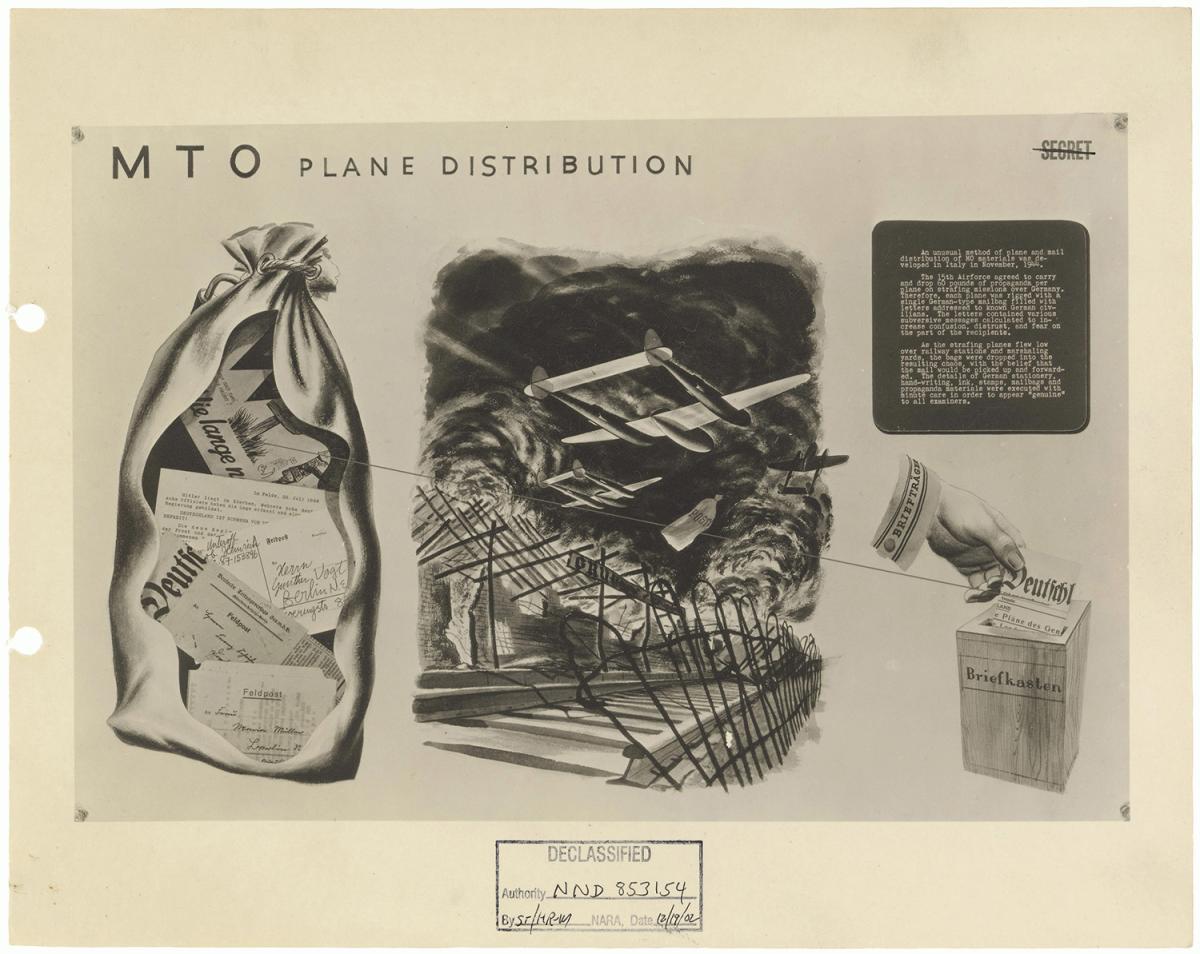

While the detailed content of "Top Secret" is still under development, other boxes in the exhibit will allow visitors to more easily understand historical stories that, while fascinating, are not as famous as the Zimmerman Telegram. A pass of the Explorer across another box will reveal the label "What was Project Cornflakes?" The next series of document screens will explain how the Office of Strategic Services—the World War II forerunner of the CIA—tried to undermine German morale by dropping anti-Nazi propaganda in the form of fake letters in counterfeit mailbags during air attacks on railroad stations. Subsequent screens will allow a visitor to follow a mission by looking at planning documents and even reproductions of the actual letters dropped on Germany.

A third use of the Explorer technology in "Top Secret" will permit visitors to study a single document in depth. Many documents in the National Archives are multiple pages. These memorandums, reports, and issue papers contain nuggets of information that are intriguing but don't lend themselves to traditional exhibit display techniques because of their size or bureaucratic tone. The Explorer will permit visitors to read a multipage document and quickly spot fascinating details.

For example, one document displayed in "Top Secret" is a 1946 memorandum written by the U.S. naval attaché in Moscow, outlining his ideas "for the conduct of a war against the Soviet Union." A visitor choosing to delve into this document can decide to read through it or skim the pages using helpful highlighting suggested by the Explorer. Although the original is seven legal-size pages, Explorer technology will make it easy to digest this interesting, but extended, example of Cold War strategy.

With more than twenty interactive exhibits and hundreds of documents and facsimiles on display, encounters with the onsite interactive exhibits will typically be quite brief. Our hope is that they will whet visitors' appetites to explore further online. A National Archives Experience web site, now in the planning stages, will challenge students and teachers to continue to learn from the National Archives Experience at home. A web version of "Top Secret" will not only replicate the interactivity of the exhibit hall but also give visitors the opportunity to go beyond merely viewing the documents they saw in Washington, D.C.

A web version of "Top Secret" has the potential to allow whole communities of students to look at and discuss what they "found" at the National Archives. Imagine, if you will, two classrooms, one in Moscow, the other in Washington, D.C., simultaneously examining the "broad outline of a plan for the conduct of a war against the Soviet Union."

Cindy in Washington asks Tasha in Moscow, "Do you think there are any documents planning for war against the United States in the Russian archives?" Another student posts a note asking if there are any good books that touch on this topic. A third inquires about projects that a small group might undertake. Such exchanges will allow students to use NARA documents as a jumping-off point in their studies and will transform an exhibit into a place where communities of learners can encounter each other and share their perspectives.

Bruce I. Bustard is on the public programs staff of the National Archives and Records Administration and was the curator of "Picturing the Century: One Hundred Years of Photographs from the National Archives." He received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Iowa.