Historic Murals Conservation at National Archives Building

Spring 2003, Vol. 35, No. 1

By Richard Blondo

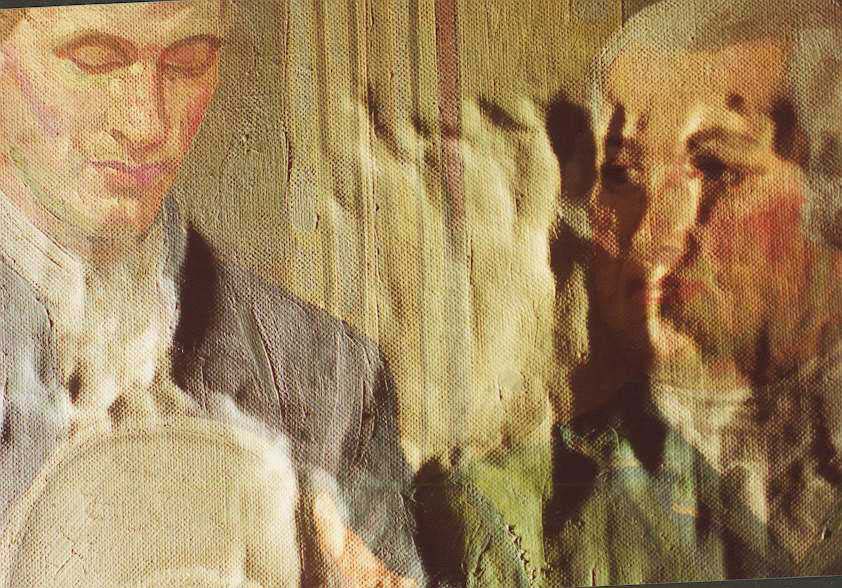

When muralist Barry Faulkner put paint to canvas in 1936 to create the monumental works destined to hang in the Rotunda of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., he knew they would not last indefinitely.

As Faulkner and three assistants painstakingly labored to create them in an immense attic high above Grand Central Station in New York, they understood it would fall to someone else in fifty years or so to clean The Declaration of Independence and The Constitution of the United States, which depict fictional scenes of the presentation of the namesake documents.

The murals, which have bracketed the permanent display of the Charters of Freedom— the original Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights— have deteriorated.

The plaster behind the canvases had crumbled in places, causing buckles and bulges. Some paint layers had separated. Dust and detritus that accumulated over the decades had caused the images to become dingy. Even though some surface cleaning had taken place in 1970, Faulkner assumed that they would need conservation near the close of the twentieth century.

So, too, did the National Archives Building itself. As part of the overall building renovation, the Rotunda was closed July 5, 2001, until September 17, 2003, thus allowing time for the murals to be removed, conserved, and reinstalled in a thorough, deliberate manner.

On October 6, 2000, the Atlantic Company of America, Inc., was awarded a $2.2-million contract to conserve the murals. Atlantic was general contractor for Olin Conservation, Inc., which planned and performed the heroic task of removing the massive murals, transporting them to a specially constructed conservation lab, restoring the artwork, and reinstalling them.

Several donors have made the murals project possible. The effort was supported in part by a grant from Save America's Treasures through a partnership between the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Gifts also came from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Bay Foundation. The conservation of the Rotunda murals was designated an official Save America's Treasures project in 1999.

Under the direction of senior conservator David Olin, the conservation team began its work in November 2000. UBS, Inc. (a scaffolding contractor), erected a special curved scaffold in the Rotunda. The mural surfaces underwent preliminary cleaning with a dilute aqueous solution to remove dust and grime. Tissue paper was adhered to the painted surface to protect the paint in preparation for removing the murals off the curved walls.

Because the murals had been affixed to the walls with a lead adhesive, the removal process had to follow stringent lead-abatement procedures. After softening the adhesive layers, the murals could be painstakingly separated from the wall. Only moderate amounts of plaster and lead adhesive remained affixed to the back of the canvas. The paintings were gradually rolled onto enormous aluminum spools as they came off the walls, then transferred from the metal spools to very large and sturdy cardboard tubes.

In December 2001, a team of movers carried the rolled murals out the back door of the Rotunda, down the marble staircase to the Pennsylvania Avenue lobby, and out the door to a waiting truck that whisked them to the conservation laboratory where they remained until November 2002, when the studio conservation work was complete.

While in the lab, remnants of plaster and adhesive were removed, and the murals were flattened. The paintings were infused with a synthetic wax resin to stabilize the aged canvas and the underlying paint. Then the tissue paper on the painted surface, the paste from the tissue paper, the layers of grime, and varnish were removed with meticulous care. Next, the murals were expertly cleaned to remove discolored varnish and coatings.

In December 2002, the murals were reinstalled onto aluminum panels newly affixed to the Rotunda walls. The panels cannot be seen, but they will make it easier to remove the murals again whenever they require conservation. After final varnishing, in-painting was done in small areas where paint had flaked off. A temporary barrier was placed over the murals in January 2003 to protect them as the Rotunda renovation proceeded.

When the Rotunda reopens in September, the murals will be seen in all their glory in the light of a new fiber-optic system designed and installed by BAND, Inc. (a lighting contractor). Barry Faulkner would be pleased.

Richard Blondo is an archivist and member of the National Archives Building Renovation Team. He joined the staff of the National Archives in 1990 after serving as an archivist since 1982 at the Maryland State Archives.