Enhancing Your Family Tree with Civil War Maps

Summer 2003, Vol. 35, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Trevor K. Plante

In the foreword to Mapping the Civil War: Featuring Rare Maps From the Library of Congress, Richard W. Stephenson aptly notes that "although a great wealth of contemporary manuscript and printed maps is extant in archives and libraries throughout the United States, especially at the National Archives and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., few authors, editors, or publishers of today's books and articles on the war avail themselves of this valuable resource." Stevenson's observation can easily be applied to genealogists as well.

In most cases, genealogists conducting research at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) tend to concentrate on textual records relating to their Civil War ancestors. Typically, their main focus is on compiled military service records, pension files, and unit records. Often overlooked, cartographic records can be a boon to researchers delving into family history. From plans of a Civil War army post or little-known navy gunboat to maps of famous battles, the maps, plans, and charts found in the Cartographic section of the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, can provide a unique, and oftentimes rewarding, perspective for genealogists.

Maps and plans, while not the starting point for your Civil War genealogy, can enhance previous research. For this reason, it is wise to master textual records relating to your Civil War ancestor prior to conducting research in cartographic records.1

The Cartographic section contains approximately eight thousand Civil War maps. While this set of records is impressive, it is just a small fraction of the approximately five million maps, plans, and charts and sixteen million aerial and satellite images maintained in the unit. The Civil War maps collection contains both manuscript and printed maps and plans. The manuscript maps include pencil sketches and original pen-and-ink drawings as well as processed maps that contain annotations in ink or pencil. Many of the Civil War manuscript maps and drawings are unique to the National Archives, while a variety of the printed maps are more common and can be found in other large repositories such as the Library of Congress.

The place to begin is with A Guide to Civil War Maps in the National Archives (1986). This book provides a general description of NARA's Civil War maps and is separated into two parts. Part one is a general guide that describes the maps by record group under these headings: Congress, Department of the Treasury, Department of War, Department of the Navy, Department of the Interior, Department of Commerce, and Other. Confederate Records (RG 109, War Department Collection of Confederate Records) are found under "Other."

Part two of the guide describes select maps and map series and is arranged by state. Entries in this section usually contain information such as title, author, size, and a detailed description of the map or maps. According to the guide, the maps described in part two "were selected for several reasons: they represent the major geographical areas in the Civil War; they possess intrinsic historic value; they contain the highest concentration of information; they are easier to read than other maps covering the same area; and they are of artistic value" (p. 73). The Cartographic Research Room maintains binders that contain color photographic reproductions of each of the select maps and plans described in part two of the guide.

During the war, mapping for the Union was primarily conducted by the U.S. Army's Topographical Engineers, (later Corps of Engineers), with the assistance of the Treasury Department's Coast Survey and the Navy's Hydrographic Office. Federal topographic and hydrographic surveys, as well as field and harbor surveys, resulted in thousands of manuscript maps and published maps and surveys produced in levels unseen prior to the war. The largest number of Civil War maps and plans in the Cartographic section are found in Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers. The Civil War - era Corps of Engineer maps are usually found in one of the following three series: the Civil Works Map File (alphanumeric), Fortifications Map File (Dr.) and the War Department Map Collection (WDMC).

Both Union and Confederate forces had topographical engineers responsible for mapping who were assigned to the staffs of various armies, corps, and divisions in the field. These engineers were instrumental in gathering information and details used in reconnaissance maps and sketches, battle maps, and base maps. In many cases, the role of the topographic engineers was determined by the importance the commander placed on the effort. This emphasis on mapping was linked not only to the situations the commanders found themselves in but also how accurate they believed the maps to be. Unfortunately, only a very small number of Confederate maps are found in NARA's holdings.2 Genealogists unfamiliar with Civil War maps will be happy to learn that many contain the names and locations of residents and property owners. To help commanders sort information, especially directions provided by locals, cartographers attempted to place the names of residents on their maps. Both Union and Confederate forces faced the problem of locals providing army commanders with advice in the form of bad or conflicting directions. "The most effective remedy for this militarily dangerous confusion was to get the name of each and every resident correctly on the map," explains Civil War map historian Earl B. McElfresh. "The idea was—and it proved to be true—that if a local knew anything at all, he would know the way to the next farm or to his immediate neighbor's house. The names worked as de facto route markers."3 Names of residents found on maps, once useful to Civil War commanders, can now be used to aid genealogists in finding the locations of their ancestors' place of residence in the 1860s.

Atlases

In the preface of the first published volume of The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (OR) Robert N. Scott wrote, "the 1st Series will embrace the formal reports, both Union and Confederate, of the first seizures of United States property in Southern States, and of all military operations in the field, with the correspondence, orders, and returns relating specially thereto, and, as proposed, is to be accompanied by an Atlas." Historians and Civil War buffs have used the OR since it was first published in the 1880s. More serious students of the war have made considerable use of the atlas, mentioned by Scott, and later published as the Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.4 The OR atlas consists of 821 maps, 106 engravings, and 209 drawings. The engravings are primarily of fortifications, and the drawings feature weapons, logistical equipment, uniforms, and Federal corps flags. These 1,136 entries are printed on 178 double-paged plates. Reference copies of each of the unbound single-sheet plates are available in the Cartographic Research Room for copying.

The Cartographic section maintains the published atlas, or the "record set," as well as maps used in compiling the atlas. There are approximately eight hundred items that fall in the latter category, including an incomplete collection of manuscript, annotated, and published maps. These records consist primarily of battlefield maps, maps showing campaign routes, maps of local terrain, and plans of Union and Confederate defenses. Most of the maps and plans are stamped "Union" or "Confederate" to indicate their source, along with a plate number corresponding to the published atlas plates. Included in this collection are manuscript maps sent in with official reports of Union officers; manuscript maps from personal collections of former Union and Confederate officers; published maps with additions or corrections made by Union or Confederate officers; and published maps, many with editorial changes, compiled by government agencies and commercial firms during and after the war.

In addition to the OR atlas, there are three other atlases that researchers may find useful: Military Maps Illustrating the Operations of the Armies of the Potomac & James May 4th 1864 to April 9th 1865 including Battlefields (RG 77, Civil Works Map File [1869]), an Atlas of the Battlefield of Antietam (RG 77, Civil Works Map File [1904 and 1908]), and An Atlas of the Battlefields of Chickamauga, Chattanooga and Vicinity (RG 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives). The last atlas contains fourteen published maps showing troop positions starting with the battle of Chickamauga, Georgia, and troop movements from Chickamauga to Chattanooga, Tennessee. It also contains plans of the engagements at Wauhatchie and Brown's Ferry, Orchard Knob, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge.

Consulting atlases can enhance Civil War genealogical research. Take, for example, the cases of Privates Josiah P. Robinson and George Bubier, who both served during the Civil War in Company K, Third Maine Volunteer Infantry. In consulting the soldiers' compiled military service records we find that both men "died at Brandy, Virginia." Further research reveals that the soldiers' remains are currently buried in Culpeper National Cemetery located in Culpeper, Virginia. According to the U.S. Army Quartermaster's published Roll of Honor, both bodies were re-interred in the National Cemetery after being removed from a site near Brandy Station.5

The unit's record of events show that Company K, Third Maine Infantry, was stationed near Brandy Station from November 1863 to April 1864. Both Bubier and Robinson had similar, yet brief, service in the Civil War. Although the Third Maine mustered into Federal service in June of 1861 under Col. Oliver O. Howard, Robinson and Bubier did not join the unit until the fall of 1863. Robinson mustered into service at Belfast, Maine, on September 3, 1863, as a substitute for Elbridge G. Colby, Jr. He died of pneumonia April 12, 1864, and according to the Roll of Honor, his body was removed from "John Minor Bott's farm, near Brandy Station." Bubier mustered into service at Portland, Maine, on October 6, 1863, as a substitute for Isaac H. Ward and died of chronic diarrhea on April 18, 1864. The Roll of Honor cites his original burial location as "J. Minor Bott's farm, near Brandy Station."

By consulting the OR atlas, it is possible to trace the location of Bott's farm. On map plate LXXXVII, sheet 2, a house with the name "J. Minor Bott" is located approximately two miles west of Brandy Station, providing the location of both soldiers' original burial site.

Battles and Campaigns

The strength of the Guide to Civil War Maps rests on its descriptions of battle and campaign maps. The majority of maps described in both parts of the guide relate to Civil War battle sites and areas that encompassed some of the larger Civil War campaigns. Many genealogists are drawn to battle and campaign maps in an effort to track the movements of their ancestors' units. The truth is, identifying specific regiments on maps can be a daunting task. More than a few maps provide details such as the topography of an area surrounding large battles or campaigns. Some maps show the locations of large Confederate and Union forces on a battlefield such as divisions, corps, or armies; fewer contain the locations of individual regiments. Even less provide a significant level of detail showing troop movements of individual regiments on the field at different stages of the battle—most notably maps prepared relating to the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg.6

In cases such as these, genealogists must use textual records and maps together. Operational reports, orders, correspondence, and personal diaries can help researchers place regiments on a specific part of a battlefield and track a unit's movements during a campaign. Maps of temporary Union and Confederate bivouac sites and encampments are harder to find. In some cases, researchers must try to match information in historic letters and reports with features on more recent large-scale topographic maps published by the U.S. Geological Survey.7

Many published military maps were surveyed and produced well after the guns of battle had fallen silent. Shortly after the Civil War, U.S. Army topographical engineers surveyed several sites of Civil War battlefields. These surveys resulted in manuscript and published topographic maps that are on a scale of two, three, or four inches to one mile and are primarily of areas in Virginia where fighting took place in 1864 and 1865.8 Several topographic maps were produced under the direction of Bvt. Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Michler and Bvt. Lt. Col. Peter Smith Michie and by order of Bvt. Maj. Gen. A. A. Humphreys. If you are working on a specific cartographer, consult the author index card file to the Civil Works Map File located in the Cartographic Research Room.

In some rare cases you can track the location of a specific regiment on a battlefield. In researching Pvt. Elisha Henderson, Company I, Eighth New York Heavy Artillery, we find that he mustered into service at Lockport, New York, on August 22, 1862, for three years. On June 3, 1864 he was wounded in action at Cold Harbor. He was later transferred to the Eighth Company, Second Battalion Veteran Reserve Corps, and was discharged at Washington, D.C. on June 28, 1865. Further research reveals a map of a portion of the Cold Harbor battlefield titled "Sketch of action near New Cold Harbor, Va." (RG 77, G-134) showing the location of the regiment during the June 3 attack and the spot where their commander, Col. Peter A. Porter, fell mortally wounded. This was the Eighth New York's first taste of combat. The unit had spent most of the war in garrison duty prior to being sent to Virginia in May 1864 as part of Grant's overland campaign. The New York unit suffered a disproportionate number of casualties in its June 3 assault against the Confederate line and Colquitt's Brigade of Hoke's Division.

Military Posts and Installations

Military posts varied in name and function and included arsenals, barracks, batteries, blockhouses, camps, cantonments, depots, subdepots, forts, military prisons, posts, subposts, presidios, stations, stockades, and redoubts. The Cartographic section maintains approximately fifteen thousand items in the Fortifications Map File in Record Group 77. Of those, about twenty-two hundred are Civil War maps and plans, the majority of them manuscript. During the war, permanent fortifications, including some held by Confederates, were manned for defense and also were used as training centers, troop depots, and prisons. The majority of maps and plans for a permanent fort pertain to its construction, maintenance, and armament prior to the war. Fewer maps and plans made during the war pertain primarily to the expansion and modification of defenses of the fortification and to armament and damage. The National Archives maintains an excellent finding aid in the Cartographic Research Room relating to posts and fortifications. These binders, titled "Military Posts," are arranged alphabetically by name of post and fort and usually provide information down to item-level descriptions. For brief historical information concerning forts and military posts, consult Robert B. Roberts, Encyclopedia of Historic Forts (1988).

In addition to records relating to military fortifications in Record Group 77, the Cartographic section maintains records related to army installations in the Post and Reservation Map File of Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General. This series contains maps and plans relating to quartermaster installations, plans of equipment used by the Quartermaster Corps, and a few miscellaneous maps. The approximately 1,235 items in this file that relate to the Civil War include city maps and maps of parts of cities showing locations of hospitals; stables and corrals; offices; barracks; camps; warehouses and other storage facilities; repair and maintenance shops; magazines; quarters for military personnel, laborers, and refugees; prisons; recruiting depots; supply depots; and related facilities. There are also ground plans of hospitals and depots. Some of the city maps and hospital and depot ground plans include floor and vertical plans of buildings; other floor and vertical plans are separate. A card file in the Cartographic Research Room relating to the Post and Reservation Map File is arranged alphabetically by state.

Even fortification drawings can be tied to genealogical research. Take the case of Pvt. (later Cpl.) Albert S. Tucker, who served with Company A, Fourth New York Heavy Artillery. From the winter of 1862 through the spring of 1864, Tucker's company served in the defenses of Washington at Forts Ethan Allen and Marcy. By consulting the map of the defenses of Washington in Record Group 77, we are able to pinpoint the location of both of these forts near Chain Bridge in Arlington, Virginia (Dr.171-97). The maps in this series contain twelve sheets (an index map and eleven detailed maps) prepared to accompany a report by Gen. John G. Barnard, who was in charge of the defenses of Washington. General Barnard served as chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac from 1861 to1862, chief engineer of the Department of Washington from 1861 to 1864, and chief engineer of the armies in the field from 1864 to 1865.9 There are several detailed plans and drawings relating to both Forts Ethan Allen and Marcy listed in the "Military Posts" finding aids binder under "Washington, D.C., Temporary Defense of (1861–65)."

If you have an ancestor who served for the Confederacy and was captured and sent to a Federal prison, you can search various series that may contain maps and plans of the facility in which he was held. Take, for example, Pvt. William G. Herndon, a Confederate conscript who was enrolled for the duration of the war on March 1, 1863, and served in Company I, Seventh Virginia Infantry. Herndon was captured on April 6, 1865, at Harper's Farm (presumably in Virginia) and sent to City Point, Virginia, then on to Point Lookout, Maryland, where he arrived on April 15, 1865. His time at the prison in Maryland was short lived, for two weeks later he died in the hospital. Herndon died on May 1, 1865, of inflammation of the lungs and was buried in the prisoner-of-war graveyard.10 The Cartographic section maintains a series of eight color manuscript ground plans of military properties at Point Lookout, including areas used as a prison for Rebels (RG 92, Maps 57-1 through 57-8).

Cities, Towns, and Counties

A good place to start researching a city, town, or county is by consulting the state and territory boxes found in the Cartographic Research Room. The boxes are arranged alphabetically by state or region, then by year. The finding aid boxes contain index cards arranged chronologically by decade, making it easier to focus on the Civil War era. Several of the cards indicate features included on the maps such as railroads, rivers, locations of cities and towns, and names of residents. Several of the maps represent regions of the United States, one or more states, and one or more counties. Many maps of cities, towns, and counties can be found in records previously described in this article, such as those found in Civil War campaign maps and city maps showing quartermaster installations.

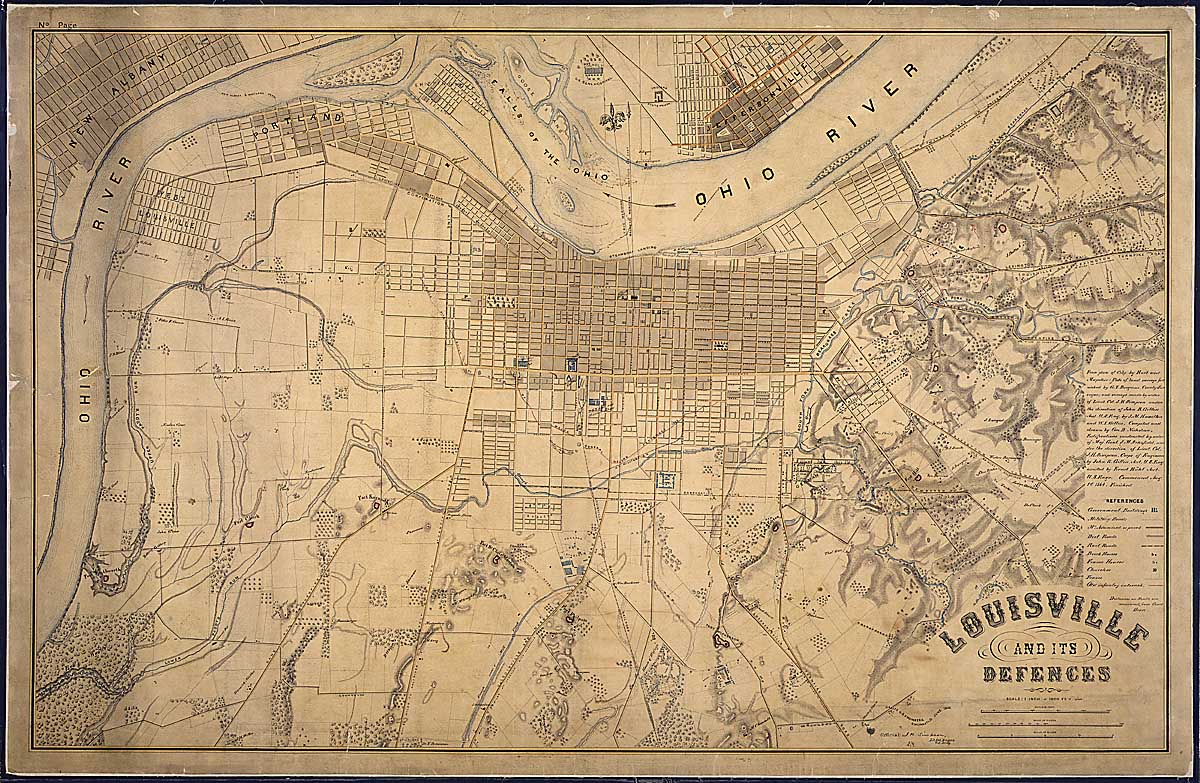

City maps often provide a level of detail that allows researchers to tie in information they already have about their ancestors. Take the case of Albert Houlett (Howlett) who served as a private in Company B, Nineteenth Ohio Infantry. Houlett, an eighteen-year-old laborer, enlisted for three years on February 29, 1864, in Youngstown, Ohio. He received a gunshot wound to the left leg at Nashville on December 5, 1864, and arrived at the Third Division, Fourth Army Corps hospital two days later. After five days he was sent to Number 14, General Hospital, in Nashville, where he spent one day receiving a simple dressing for his leg wound. On December 14 he was admitted to the Crittenden General Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, where he spent the next three months in Ward 3.11 Research in the Cartographic section uncovers a map depicting the city of Louisville and its defenses (RG 77, T 124-3). The map shows government buildings in blue, including Crittenden U.S. General Hospital, a military prison, U.S. stables, U.S. wagon and harness shops, and Taylor Barracks. The Crittenden General Hospital is located between Magazine Street and Broadway and Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets.

Charts

The Guide to Civil War Maps describes sixty-one charts, primarily of the eastern and gulf coasts of the United States, found in Record Group 23, Records of the Coast and Geodetic Survey. The guide lists several chart titles that can provide researchers with a general idea of the geographic area covered by each chart. For a visual representation of the coverage of each chart, consult one of the Catalogue of Charts books found in the Cartographic Research Room. The catalogs also provide information such as catalog or chart number, title, state, class, scale, size of borders, date of last edition, aids to navigation, and price (cost to purchase at the time of publication).

Ship Plans

Historic plans of U.S. Navy ships can offer researchers a unique perspective not found in viewing photographs. Ship plans, found in Record Group 19, Records of the Bureau of Ships, may include detailed drawings of a particular vessel. The drawings may provide not only exterior details but also views inside the ship and hull designs not visible below the water line. These plans can come in the form of inboard and outboard profiles, deck plans, or hull designs. Before conducting research in these records, make sure you have information pertaining to the correct navy vessel. Several ships served at different times under the same name, so first consult the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships to find the dates of service of the vessel you are researching. The finding aids for drawings and plans of U.S. Navy ships are located in binders in the Cartographic Research Room and are arranged alphabetically by the name of the vessel. The case of John Dunlap, an African American who served as an officers' cook on USS Monadnock, is an example of how to use ship plans and charts to supplement one's genealogical research. The Monadnock, an ironclad, twin-screw steamer, participated in the attack on Fort Fisher, North Carolina, on January 15, 1865. Further research reveals that there is a chart (OR Atlas plate LXXXV, sheet 3) of the area around Fort Fisher showing the attack lines of the Union vessels. The Monadnock is located on the northern end of the line of ships closest to shore. The ship plans binder lists quite a few drawings relating to the Monadnock, including a plan of the main and berth decks and plans of the inboard and outboard profiles. Dunlap, who enlisted in Washington, D.C., on March 25, 1862, appears on the ship's muster rolls before and after January 1865, showing he was most likely on board the vessel at the time of the attack.

For more information on other records held by the Cartographic section, consult the Guide to Cartographic Records in the National Archives (1971) and "Taking Measure of America: Records in the Cartographic and Architectural Branch," by Stuart L. Butler and Graeme McCluggage (Prologue, Spring 1991). Researchers can also consult chapter 19 of the Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives of the United States (3rd ed.). The chapter on cartographic records provides a basic description of census records, general land office records, military records, topographical quadrangle maps, county soil maps, captured and abandoned property, and Bureau of Indian Affairs maps.12

Researchers will also find limited success using the Archival Research Catalog (ARC), an online catalog of NARA's nationwide holdings. Researchers can search by keyword or location and even restrict results to those that return digitized images. In the initial search mode, select the Cartographic unit under the location field to narrow the inquiry. Some of the more popular Civil War maps and plans have been digitized, including a limited number relating to Gettysburg, Antietam, Vicksburg, Freedman's Village, and Point Lookout. ARC currently contains 308 digitized maps and charts and 15 architectural and engineer drawings. The online catalog is still in its infancy, and more descriptions and digitized copies will continue to be added in the future.

For recently published books on the subject, consult Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War (1999) by Earl B. McElfresh; Maps of the Civil War: The Roads They Took (1998) by David Phillips; and Historical Maps of Civil War Battlefields (2000) by Michael Sharpe. Also helpful is a pamphlet produced by the U.S. Geological Survey, "Using Maps in Genealogy," Fact Sheet 099-02 (September 2002) (https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2002/0099/report.pdf.) The pamphlet gives advice on how to use maps for genealogy and provides information on using gazetteers to find unfamiliar place names. It also provides information on map collections, map bibliographies, and using USGS topographic maps.

We would be remiss if we did not mention that the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., also maintains an excellent collection of Civil War–era maps in their Geography and Map Division. Consult Richard W. Stephenson's Civil War Maps: An Annotated List of Maps and Atlases in the Library of Congress (2nd ed., 1989) and Mapping the Civil War: Featuring Rare Maps from the Library of Congress (1992) by Christopher Nelson.

For more information on maps, plans, and charts at the National Archives, please write to Cartographic Records, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-C), National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, Maryland 20740-6001. No forms are needed when making your request. Researchers can also send an email inquiry to carto@nara.gov.

Notes

1 If you are just beginning Civil War research at the National Archives, we recommend reading the articles by Michael Musick that appeared in the Summer, Fall and Winter issues of Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, Vol. 27, nos. 2–4 (also available at http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/index/1995.html#C).

2 Two of the most famous collections of Confederate maps are the Jedediah Hotchkiss maps at the Library of Congress and the Gilmer-Campbell maps located at the Virginia Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the U.S. Military Academy, and the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

3 Earl B. McElfresh, Maps and Mapmakers of the Civil War (1999), p. 55.

4 The OR atlas is no longer available for sale from the Government Printing Office. However, facsimile editions were published in 1958 by Thomas Yoseloff of New York City and in 1978 by Arno Press and Crown Publishers and again in 1983 as The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War. This last, large, oversize, volume is available at many reference and university libraries.

5 George Bubier and Josiah P. Robinson, Third Maine Volunteer Infantry, Compiled Military Service Records, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780s–1917, Record Group (RG) 94, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC. Roll of Honor, No. XV, Names of Soldiers who Died in Defense of the American Union Interred in the National Cemeteries (1868), Culpeper Court-House, pp. 119 and 133.

6 The Antietam Atlas mentioned earlier in the article provides plates showing troop locations at specific times throughout the day of September 17, 1862. For detailed maps showing troop positions for each of day of the battle of Gettysburg, July 1–3, 1862, see RG 77, E-119-1 through E-119-3. These three maps were based on surveys of the battlefield conducted in 1868 and 1869 and revised in 1869 producing a twenty-sheet map at an amazing scale of 1 inch to 200 feet (see RG 77, E-81).

7 The Cartographic section maintains historic USGS topographic maps at a scale of 1:24,000 in Records of the U.S. Geological Survey, RG 57.

8 Several of these maps were published in 1869 in an atlas illustrating the campaigns of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James. There are two editions of this atlas entitled Military Maps Illustrating the Operations of the Armies of the Potomac & James May 4th 1864 to April 9th 1865 including Battlefields (RG 77, Civil Works Map File, Pub. 1869, 2 atlases).

9 Richard W. Stephenson, Civil War Maps: An Annotated List of Maps and Atlases in the Library of Congress (2nd ed.,1989), p. 3.

10 W. G. Herndon, CMSR, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, RG 109, NAB. The name Wm. G. Herndon is found on one of the cards in the CMSR and also appears under Point Lookout, MD, p. 288, vol. 2, Register of Confederate Soldiers and Sailors who Died in Federal Prisons and Military Hospitals in the North, Entry 700, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, RG 92, NAB.

11 Carded Medical Records, RG 94, NAB. On March 21, 1865, Houlett was transferred to Columbus, OH. He spent March 22 to 24 on the U.S.A. Hospital Steamer Ginnie Hopkins. Eventually he arrived at the general hospital in Cleveland, OH, and received a disability discharge on July 10, 1865. The name is spelled a variety of ways in several records including Houlett, Houlette, Howlett, and Howlette.

12 For additional information on records in the Cartographic section see General Information Leaflet Number 26, Cartographic and Architectural Records, available on our web site at www.archives.gov/publications/general_information_leaflets/26.html.

Trevor K. Plante is a reference archivist in the Old Military and Civil Records unit at the National Archives and Records Administration who specializes in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century military records.