American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell

Winter 2003, Vol. 35, No. 4

By Lee A. Gladwin

John M. Jacobs had been in Manila when the Japanese captured the Philippines in the early stages of World War II, and now, in 1944, he was a prisoner of war, or POW, in the Bilibid Prison in Manila. There, he and other American and Allied POWs were often forced to do heavy labor.

With U.S. forces about to retake the islands in late 1944, the Japanese began moving Jacobs and thousands of other POWs to locations closer to Japan. To do so, Japanese troops herded them by the hundreds into the holds of merchant ships that also carried supplies and weapons.

Jacobs ended up on the Oryoku Maru:

"We threw our packs into the deep hold and quickly followed down the long ladder into the darkness, herded by the guards and their bayonets," Jacobs recalled several years later in a narrative, noting that where he was being held was not as crowded as some others:

The prisoners had been so crowded in these other holds that they couldn't even get air to breathe. They went crazy, cut and bit each other through the arms and legs and sucked their blood. In order to keep from being murdered, many had to climb the ladders and were promptly shot by guards. Between twenty and thirty prisoners had died of suffocation or were murdered during the night.

If that was not bad enough, the merchant ship was a target for U.S. planes and submarines, whose crews did not know they were also loaded with American and Allied POWs. In mid-December 1944, they attacked and sank the Oryoku Maru. Jacobs survived the ordeal when he escaped and swam to shore while American planes were sinking the ships he and the other POWs had been on.

Jacobs's story and those of other American POWs held by the Japanese during World War II came to light when NARA archivists were trying to decipher punch card codes as they assembled material for the National Archives' new online search tool Access to Archival Databases (AAD), which debuted on NARA's web site, www.archives.gov, last year.

AAD allows researchers to search approximately 350 files, including one that contains records of American prisoners of war during World War II. And that particular database includes information on American and Allied POWs on five Japanese ships.

In Death on the Hellships: Prisoners at Sea in the Pacific War, Gregory Michno estimates that more than 126,000 Allied prisoners of war were transported in 156 voyages on 134 Japanese merchant ships. More than 21,000 Americans were killed or injured from "friendly fire" from American submarines or planes as a result of being POWs on what the survivors called "hell ships."

This is the story of five of those "hell ships" and the fate of the POWs who were on them.

World War II Punch Cards Lead to Story of POWs

While American and Allied prisoners of war suffered at the hands of their Japanese captors, their families and friends—and their government—usually knew little of their whereabouts or conditions. Information about them was difficult to get, and often it traveled a circuitous route.

The International Red Cross, based in Bern, Switzerland, was the main conduit for this information. Throughout World War II, the Red Cross routinely received and sent lists of POWs to the U.S. Army Office of the Provost Marshal General. Once there, the Prisoner of War Information Bureau sent letters to the next of kin and copies of casualty and POW reports to the Office of the Adjutant General, Machine Records Branch.

The Machine Records Branch produced a series of IBM punch card records on U.S. military and civilian prisoners of war and internees, as well as for some Allied internees. The branch used these cards, together with many others, to generate monthly logistical reports of the current and actual strengths of army and army air force units worldwide.

The U.S. Army transferred these punch card records of World War II POWs to the National Archives as a unique series in its 1959 transfer of all of the U.S. Army's departmental archives. The punch cards came with tabs that separated them into presorted groups. In 1978 the Veterans Administration migrated the cards for the American Military POWs Returned Alive from the European Theater (92,493 records) and American Military POWs Returned Alive from the Pacific Theater (19,202 records) to an electronic format for a study of repatriated U.S. military prisoners of war.

In 1995 NARA migrated the remaining punch card records to an electronic format and in June 2002 preserved all of the migrated records in a single data file. A small number of the punch cards were too badly bent or damaged to be migrated and are available only as paper copies. The World War II POW Data File contains 143,374 records and is 11,469,920 bytes in size.

Potentially, every record documents the type of prisoner, whether detained in an enemy or in a neutral country, and whether repatriated, deceased, or an escapee. Each prisoner's record may provide serial number, name, grade and grade code, service code, arm of service and its code, date reported, race, state of residence, type of organization, parent unit number and type, where captured, latest report date, source of report, status, detaining power, detention camp code, and whether the POW was on a Japanese ship that sank or if he died during transport from the Philippine Islands to Japan.

Understanding the origins of the "Ship Sinkings" codes became crucial when it was decided to include the World War II Data File among those available in AAD. Only after researching textual records related to the ship sinkings was it possible to clarify the meaning of these codes for the researcher.

Of the 134 Japanese transports noted by Michino, only five were singled out for special coding and inclusion at the end of a list of Japanese POW camps: Shinyo, Arisan, Oryoku, Enoura, and Brazil, all called "marus." Why only these transports were selected for coding was a mystery. It was assumed that POW records with these ship codes indicated individuals who died when the ships were sunk.

Further, it was believed that one of the letters indicated month of sinking; e.g., SS for September Sinking, OS for October Sinking, and EDS and BDS for December Sinkings. The meaning or significance of the XDS code was unknown.

Japanese lists of POWs provided through the Red Cross were often incomplete and late, if they arrived at all. These lists were the basic source of information but not the only one. Reports of air crews who saw pilots bail out over enemy territory, escaped prisoners, captured documents, and interrogations of enemy POWs also provided information in addition to or in the absence of the lists. Sometimes ULTRA sources provided information on POWs. "ULTRA" was the British term for intelligence gained from the interception, decryption, and decoding of enemy radio signals. While extremely useful in the absence of any other source of information, ULTRA proved a double-edged sword: the information could not be used without revealing its source to the enemy.

Obtaining intelligence from intercepted radio messages was difficult, for the Japanese used an elaborate system of codebooks and rules to encipher their messages. But there were a number of U.S. and Allied intelligence gathering units involved in intercepting, decrypting, translating, and reporting Japanese radio traffic. Units were established in Australia and elsewhere in the Pacific theater, and they had the support of installations in the Washington, D.C., area; Bletchly Park, England; Delhi, India; and Colombo, Ceylon.

These units tracked convoys and individual combat and merchant ships and meticulously recorded their numbers on index cards by name and date. Tonnage was noted for reporting purposes. During January and February of 1944, approximately 3,700 index cards were created in the ongoing effort to identify, describe, and locate the marus.

The Shinyo Maru: An Explosion, and Survival, for Some POWs

On August 14, 1944, a Japanese naval message was intercepted on its way from Manila to Tokyo:

I have held preliminary negotiations with the Naval authorities in Manila in regard to the cargo of the Shinyo Maru As a result, it was decided to unload the rice and cement at Zamboanga and the miscellaneous goods, ([iron ?] products, etc.) at Manila. (I understand that the Shinyo Maru is now at anchor at Zamboanga. It is to be put to urgent use by the Navy, and it will therefore be absolutely impossible for it to sail to the Davao or Palau areas.)

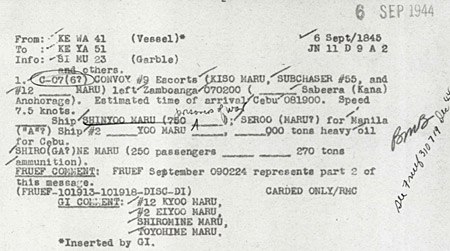

An intercept of August 18 ordered that "Shinyo Maru is to proceed from Zamboanga to Cebu and then transport something on to Manila." According to a September 1 message, the "something" was "evacuees from Palau." A subsequent message on September 6 stated that the C-076 convoy would depart for Cebu on September 7 at 2 a.m. In that convoy would be the Shinyo Maru transporting "750 troops for Manila via Cebu."

At 4:37 p.m. on September 7, Lt. Comdr. E. H. Nowell, skipper of the U.S. submarine Paddle, sighted the convoy off the west coast of Mindanao at Sindangan Point and prepared to fire two torpedoes at Shinyo Maru.

Crowded into the foul and steamy holds of an unidentified ship were 750 U.S. POWs, most of them survivors of POW Camp #2-Davao, Mindanao, Philippines. Since February 29, 1944, 650 officers and enlistees labored on a Japanese airfield at Lasang. The other 100 had similarly worked on another airfield south of Davao. All 750 were marched shoeless to the Tabunco pier on August 19. On August 20, they were packed into the holds of the ship.

Late in the afternoon of August 24, the ship arrived in Zamboanga. The prisoners had no idea of where they were until the men who went topside to empty the latrine cans returned to tell them. "By this time the men were all very dirty [and] many suffering from heat rash and frequent blackouts," recalled 1st Lt. John J. Morrett. The "Japanese allowed the men up on deck twice to run through a hose sprinkling salt water." Morrett commented. "It was hardly a bath but helped considerably."

After ten days of waiting in the harbor, they were transferred to the Shinyo Maru on September 4. On September 7, hatch covers were placed more closely together and secured by ropes to prevent lifting from below. They sailed for fourteen hours without an air raid alert, and many "felt that the worst part of the journey was over."

"Suddenly," Morrett recalled, "there was a terrific explosion immediately followed by a second one," and "heavy obstacles came crashing down from above." Dust filled the air, and bleeding men lay "all over each other in mangled positions, arms, legs, and bodies broken." He struggled up to the deck and found it "strewn [with] the mangled bodies of Japanese soldiers."

Nearby, surviving Japanese soldiers fired at Americans swimming in the water or shot at those struggling up from the holds.

Morrett dove overboard and swam ashore. While swimming, he heard "a terrific cracking sound as if very heavy tissue paper was being crushed together, then the boat seemed to bend up in the middle and was finally swallowed up by the water." Friendly Filipinos and members of the "Volunteer Guards" assisted him and the other eighty-three survivors in returning to the United States.

The death of Shinyo Maru was duly noted by a Japanese cipher clerk at 1650 hours on September 7, the victim of a "torpedo attack." An intercept of September 10 reported 150 Japanese army casualties. Lt. Commander Nowell later reported that "this is probably the attack in which U.S. POWs were sunk, and swam ashore."

On December 31, 1944, a note was added to the message of September 6 that Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC) interpreted as ""SHINYOO MARU (750 troops for Manila via Cebu." In pencil was written: "FRUEF (31 Dec '44) gets 750 Ps/W"! FRUPAC misinterpreted this crucial part of the message with fatal consequences.

The Arisan Maru: A Navy Boatswain Survives

On the eve of and during the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 23–27, 1944), intercepts and intelligence summaries focused upon the movements of "#1 Diversion Attack Force," "#1 and #2 Replenishment Force," and other sea, air, and land units. Occasional references to patrol boats, merchant ships, and convoys are found. On October 24, 1944, the following message was decrypted: "The Luzon Straits Force is assigned to 2 unidentified Convoys and the Naval Air Force is assigned to 2 other unidentified Convoys."

One of these convoys may have been the Harukaze Convoy, which departed Manila for Takao, Formosa, on October 21, 1944. In that convoy was the Arisan Maru. Its cargo: 1,783 American prisoners of war.

Boatswain Martin Binder was among the prisoners compressed into hold two of the Arisan Maru on October 11. There was standing room only. On the following day, the Japanese mercifully moved about 800 prisoners to hold one, which was partially filled with coal. Mercy did not, however, extend to providing water, and several died of heat exhaustion.

To the surprise of the POWs, the ship took a southerly route, away from their Formosa destination, narrowly missing a devastating Allied air attack on Manila airfields and harbor. The Arisan Maru returned to Manila a few days later when it was thought safe to do so, joined the convoy, and departed on October 20.

It was nearly dinnertime on October 24. About twenty prisoners were on deck preparing the meal. The ship was near Shoonan, off the eastern coast of China. Binder and the others suddenly "felt the jar caused by hits of two torpedoes." Arisan Maru stopped dead in the water. After severing the rope ladder leading down into the first hold, the Japanese abandoned ship. Binder was first to escape from hold two and assisted in lowering a ladder down to those in hold one. Ropes were thrown down to those in hold two, as well. Wearing life belts and clinging to rafts, hatch boards, and any other flotsam and jetsam, the prisoners struggled in the rough waters of the Pacific.

Japanese destroyers deliberately pulled away from the men struggling to reach them. Binder survived by clinging to a raft and was later rescued by a Japanese transport that took him to Japan. On October 25 a Japanese army shipping message was intercepted stating "that the Arisan Maru had been loaded with 1,783 men (presumably prisoners)."

The Oryoku Maru: After Sinking, Many Americans Still POWs

On October 20, 1944, Gen. Douglas MacArthur kept his promise and "returned" to Leyte Gulf. The conquest of the Philippines had begun. His objective on December 14 was Mindoro Island, a base for launching air attacks on his next target, Luzon. The U.S. invasion fleet entered the Sulu Sea and pushed northward.

A note concerning prisoners of war appeared in the Summary of Radio Intelligence on December 14:

On 7 December, Assistant C. of S. [Chief of Staff] of the Army General Staff in Tokyo sent a long message to Manila concerning the questioning of POWs, apparently from [U.S.] Task Force 38 carrier groups. The message indicates that considerable importance is being attached to information believed in the possession of these POWs, particularly as regards U.S. carrier strength. The message states that thorough interrogation should be conducted, as the present strength of U.S. CVs [aircraft carriers] will exert a very important influence on future decisions and policy. It is also desired that POWs be sent to Tokyo by air as soon as field interrogation is complete so that further questioning may be carried out in cooperation with the Naval General Staff.

Allied attacks on Japanese naval forces greatly reduced the number of warships available for convoy escort. In apparent response to Manila about delays in the arrivals of the high-speed transports Arisan Maru and Oryoku Maru, the Shipping Headquarters Takao Branch fired back:

Escort for the Arimasan Maru (JTGL 8696T) sailing alone is just as necessary as for convoys. _____ we have reached a still more critical period of insufficient escort-strength after accelerating the loading and unloading of the Arimasan Maru (JTGL 8696T) _____ Ooryoku Maru (JSKL 7362T) in so far as possible ______.

Both were scheduled to leave Takao on December 5 and arrive at Manila on December 10.

Oryoku Maru's cargo included the "4th Medium Mortar Battalion, consisting of 23 officers and 535 non-commissioned officers and troops, 1350 cases of unit baggage, 12 artillery pieces, 2430 cases of ammunition . . . 14 cases of gasoline, four trucks," and many more reinforcements and supplies. An intercept of December 13 announced, "Oryoku Maru is part of convoy with 2054 troops aboard." The ship was to be loaded and ready to sail with the MATA-37 convoy on December 14. On that date, the Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru prepared to sail from Takao to Manila.

During a lull in Allied air attacks, the Japanese ordered American medical officers at Bilibid Prison to examine and prepare a list of all prisoners who could depart with the last of the POW transports. On the morning of December 12, the roll was read. That evening the departees bade farewell to friends and packed what little remained of their belongings. They were awakened at 4 a.m. the following morning, fed a bit of breakfast, and then all 1,619 POWs marched to Manila's Pier 7. Awaiting them was the Oryoku Maru, its name dimly visible through battleship-gray paint. No Red Cross or other markings were apparent to distinguish her from any other combat craft. The ship bristled with antiaircraft guns.

First to embark were women and children in bright kimonos and merchant seamen stranded when their ships were sunk in the harbor. Not until dusk were the prisoners loaded into three holds of the ship.

The convoy was soon under way, bound for Takao, Formosa, and Moji, Japan. Divided into groups of twenty, the prisoners were "fed small amounts of rice, fish and water." Crowded together on the floor, there was little sleep to be found as cramped muscles jerked spasmodically and neighbors were suddenly jostled. "A Catholic padre, who had recently been brought from Mindanao, stood the whole night through that others might rest," refusing to trade places with one of those on the floor, recalled John M. Jacobs, one of the survivors, in a narrative later.

On the morning of December 14, after collecting the bucket from the ship's kitchen, the mess representatives returned to their holds and began doling out rations. Suddenly, there was the roar of planes and the firing of the antiaircraft guns. Prisoners heard the acceleration of plane engines as they went into their dives and then pulled up, followed by the deafening detonations of bombs. Several messmates scrambled down the ladders, buckets in hand, as bullets ricocheted about them. One of them, Chaplain Ed Nagle, was struck through the leg. "He continued down the long ladder with the bucket, blood streaming from his wound," Jacobs recalled.

Huddled together, seeking emotional refuge from the "terrific explosions and concussions," according to Jacobs, the prisoners "were shaken about like a dog shakes a rat." They "were covered with rust chips and bomb dust." Between raids, they tended the wounded with what scanty supplies were left. Some tried to eat the now dirty rice but found they had lost their appetites. From the depths of this inferno came the voice of Father Duffy praying, "Forgive them. They know not what they do."

Above the holds, gun crews stood and died at their guns. Their blood trickled over the deck and into the holds. New crews replaced the fallen, just as the next flight dived and strafed the decks. The spray of bullets was quickly succeeded by the detonations of bombs that "bounced" the ship about "like a cork in a tub." In futile defiance, the Japanese gun crew officer shook his spear at the onrushing planes.

The POWs endured seventeen such attacks before sunset. Only Oryoku Maru remained afloat. All other craft were sunk or departed. That night a Japanese officer ordered some medical officers topside to tend the wounded. "Decks, cabins, dining room and parlor were littered with dead and dying," reported one officer. Working by candlelight without medicine or bandages, the doctors rendered what little assistance they could. Realizing the hopelessness of the situation, the Japanese sent the medical teams back to their holds.

The night was filled with the "groans of the wounded" and "the screams of the crazed." John Jacobs remembered, "[Latrine] Buckets were soon filled to overflowing, but the guards did not permit them to be brought topside for emptying. Above the holds, the prisoners could hear the sounds of passengers being loaded into lifeboats. A cable broke, spilling screaming women and children into the sea. By morning, passenger removal was completed." To those in the holds, it was apparent the "Japanese intended leaving us to go down with the ship."

On the morning of December 15, U.S. Navy aircraft returned to finish their task. Their bullets and bombs went unchallenged. Between attacks, a Japanese guard shouted down to the POWs that they were going ashore, wounded first. About fifty healthy prisoners rushed up the ladder, only to be surprised by returning planes. Minutes later, Jacobs clambered up the ladder, discarded shoes and clothes, and dove into the water as three planes soared overhead. With the aid of some floating bamboo, he swam the half-mile to shore.

Jacobs and two others collapsed on a seawall, but only briefly. A Japanese soldier suddenly emerged from the neighboring woods, raised his rifle, and fired at one of Jacob's companions. The soldier slumped, Jacobs recalled, "blood pouring out of his heart." The Japanese soldier then took aim at Jacobs, who dove into the water with his surviving companion. Safe for the moment, they watched as the enemy soldier shot at other prisoners swimming for shore.

Oryoku Maru sank near Olongapo Naval Station, Subic Bay, Luzon. Surviving prisoners were assembled nearby at some tennis courts. Of the 1,619 POWs aboard the "hell ship," as they termed it, only 1,290 answered roll call.

Not until December 18 did the Japanese transmit details of the sinking. In a lengthy seven-part message, the attack was described and the presence of American POWs was first announced:

1. The OORYOKU MARU (JSKL 7362T) was bombed and strafed by about 200 enemy planes in Subic Bay on 14 December from 0910 to 1700. In this attack it received a total of 6 direct hits[,] 1 in each of the following places: the left side of the passenger quarters, the front part of the right side of the #1 hold, a center part of port side, rear part of coal box, starboard side of passenger quarters, and port side of passenger quarters. And on the next day, the 15th, beginning at 0800, it was attacked again by almost the same number of enemy planes.

3. Things on board: 546 Japanese nationals begin evacuated (____children____) unhurt.

Of 1191 shipwrecked, ship personnel returning home, 10 were killed, the rest unhurt. Of the 1619 prisoners, about 250 dead. The others were all picked up.

On December 20, Manila informed Hiroshima of their intent to transport overland "about 1300 white prisoners who were shipwrecked on the Oryoku Maru." They expected to have this done by December 24.

From December 15 to 21, 1944, survivors of the Oryoku Maru sinking were held at the double tennis courts at Olongapo Naval Station. No food or medical aid was provided the first two days. Afterward, they were allowed five spoonfuls of raw rice daily and some water from a tap on the tennis court. On December 21 the POWs were transported from Olongapo Naval Station to San Fernando, Pampanga, where they were confined in a jail and movie theatre.

Japanese Lt. Junsaburo Toshino told Lt. Col. E. Carl Engelhart that those prisoners too badly wounded to continue the trip were to be selected for transport back to Bilibid Prison. Fifteen men were selected. On December 22, the fifteen were taken not to Bilibid but to a cemetery, where they were executed by decapitation or bayonet thrust and buried in a mass grave.

On December 24, the remaining prisoners were loaded onto trains and sent to San Fernando, La Union. Train windows were closed, and the prisoners suffered from the heat. From December 24 to 27, the POWs were held in a school house and, later, on a beach, at San Fernando, La Union. They were permitted "one handful of rice and a canteen of water." So terrible was their thirst in that broiling sun that many drank sea water, often dying as a result.

The Brazil Maru and the Enoura Maru: Finishing the Journey into Hell

On December 27, the prisoners at San Fernando boarded the Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru and sailed for Takao, Formosa, part of the TAMA #36 convoy, bound for the POW camps near Moji, Japan. Landing craft ferried them from the pier to the ships. To board the landing boats, the men ha to leap twenty to twenty-five feet straight down into the boats. Any reluctance was swiftly punished by a bayonet prodding. Many were injured in their jumps.

Both Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru had been hauling livestock, and no effort had been made to clean out the manure before placing the prisoners in the holds. There were no attacks or food during the voyage to Takao. The ships docked there on New Year's Day 1945, and the prisoners received their first food since leaving San Fernando, "five moldy hardtack type of biscuits" and some rice. Each day guards came down to count the number of survivors. Twenty-one prisoners were buried at sea during the voyage to Takao, five from Brazil Maru and sixteen from Enoura Maru.

Both Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru were listed as undergoing repairs on January 8, 1945, accounting for their delayed departure for Moji, Japan. On January 9, MacArthur's forces invaded Luzon. A simultaneous attack was made on Takao. John Jacobs, aboard Enoura Maru, recalled that they were just finishing their only meal of the day when the first air raid sounded. Panic spread in the hold as men tried to remove the hatch covers.

"A young captain stood up and told the prisoners to sit where they were, that they were just as safe in one place as they were in another." Moments later, "there was a blinding orange flash and a deafening explosion followed by blindness." Planks, hatches and other debris flew through the air. Some men were pinned by the hatches. One floor gave way, dropping prisoners thirty or forty feet below. When it was over, only three doctors remained to care for seventy-five injured. Thirty-five dead were placed in a pile. With the hatches gone, the temperature plummeted.

On January 10, Jacobs was asked to look into the forward hold where a bomb fragment left a gaping hole. "There were mangled Americans, some 300 of them, piled three deep and pinned down with large steel girders and hatch covers," he remembered.

On January 12, forty-five coffins were removed to the beach and burned. One-hundred and fifty more were taken to a cemetery the following day. This gruesome task done, the survivors of this second attack were transferred from Enoura Maru to Brazil Maru. Finally, on January 14, they sailed for Moji, Japan, arriving there on January 29. Of the 1,619 POWs who boarded Oryoku Maru on December 14, 1944, 497 arrived in Moji. An estimated 500 died aboard the Brazil Maru during the voyage from Takao to Moji. Soon after Brazil Maru's arrival, wrote E. R. Haase later in his diary, "senior medical officers were asked to sign 1001 death certificates representing our loss from 13 December to Jan 31, a rather heavy toll."

Japanese radio traffic records the unfolding tragedy from the enemy's side. A message of January 10, 1945, from First Shipping Headquarters, Takao Branch. to Tokyo stated that "ENOURA MARU (JOVS) suffered some damage to the outer plates caused by near misses. Personnel killed, wounded, and missing—approximately 100." It was soon realized that the damage was much more serious, and a message to Taihoku stated that 925 prisoners were being transferred from Enoura Maru to the Brazil Maru. This figure would contrast sharply with the one later provided by the Japanese.

Counting the Costs: A Search for the Truth

A complete, timely, and accurate accounting of American POWs was of paramount importance to the Chiefs of Staff, who needed the information for logistical planning, as well as to the friends and families awaiting word of missing loved ones at home.

Standard procedure during the war was for Axis and neutral countries where POWs were interned to inform the U.S. State Department or Office of the Provost Marshal General of prisoners taken. This was usually done via the International Red Cross. In the case of the "hell ship" victims, the Japanese War Prisoners Information Bureau compiled lists and sent them to their consulate in Bern for transmission to the Red Cross. Getting information from the Japanese often took a lot of time and repeated attempts.

As early as September 19, 1944, the State Department made inquiry concerning the numbers of those who died, escaped, or were recaptured following the sinking of Shinyo Maru. Apparently, there was no adequate response, as another inquiry was made January 11, 1945. Similarly, the Japanese were slow to furnish lists of casualties following the sinking of Arisan Maru. State made further inquiries on January 10 and February 22. Initial inquiry concerning the sinking of Oryoku Maru was not made until March 5.

Though some in Tokyo thought the American sinking of Enoura Maru would make great propaganda, the Japanese had a problem. How could they tout the number of dead without revealing their own responsibility for the ghastly figures that arose after Oryoku Maru was at the bottom of the harbor? They could not resolve this dilemma, and no propaganda broadcast was ever made.

Their dilemma was rendered moot when MacArthur's forces liberated Bilibid Prison. A roster of "Prisoners of War Believed to be Missing (Japanese Records)" or dead was submitted to the general on February 5, 1945. It contained 296 names. A copy of the list was sent to the Adjutant General's Office on March 13. Its contents, however, may have been known to the State Department and the Office of the Provost Marshal General before then.

As late as April 20, there was still no definitive word from the Japanese concerning Oryoku Maru. Maj. Gen. Archer L. Lerch stated what was known at the time by the Office of the Provost Marshal General's Office:

On 15 December 1944, a Japanese transport carrying 1600 prisoners from Cabanatuan was sunk close to shore in Subic Bay. Of this number, 2 were rescued and subsequently returned to United States military control. Approximately 1200 were retaken by the Japanese, and the remainder are believed to have been lost.

He added that the State Department had "made strong representations to the Japanese Government demanding lists showing the new locations of our prisoners who have survived, and lists of those who may have been lost due to the sinking of these transports." In addition, the War Department was "making similar requests through the International Committee of the Red Cross." So far, only a list of prisoners aboard Shinyo Maru had been received.

Although there were other sources of intelligence about the POWs and the ship sinking, some of the communications intelligence could not be shared outside a small circle without betraying their source. Figures varied depending upon who collected the information and from what sources, i.e., intercepts, captured Japanese documents, survivor accounts, etc. One, perhaps the earliest of these, bore the dual stamp "TOP SECRET ULTRA," the highest of Allied security classifications. Internal evidence in an accompanying text indicates that this table was compiled some time after April 20, 1945.

Another summary table, "Extracts of P/W Camp Information," was prepared by the U.S. War Department, Military Intelligence Division, Military Intelligence Service, Captured Personnel and Material Branch "from various sources." The distribution list was a who's who of U.S. and British intelligence gathering agencies. This report set the number of casualties from the Oryoku Maru sinking at 365. A "Magic Far East Summary" of March 29, 1945, similarly put the number at 363, and both were in virtual agreement as to casualties from the Shinyo Maru and Arisan Maru sinkings. ("Magic" was the code name for intercepted Japanese consular traffic.)

In July 1945 the Japanese War Prisoners Information Bureau sent the following cable to Bern:

ST/9 Investigations concerning a ship transporting prisoners of war from the Philippines homeward revealed that the ship in question met gun and bomb attacks by enemy planes on several occasions and that out of the 1619 prisoners on board 942 were killed instantly or died subsequently of wounds caused by bomb explosions while 59 died of illness.

Names of a part of the survivors have already been given in lists FM/56 and FM/57. As for others and those dead a notification will be sent later on.

These figures were included in the State Department's "Summary of Prisoner of War Ship Sinkings (Far East) 1944" and repeated in a letter dated September 5, 1945: "Lost 942, Died Later 59, Survivors 618."

The figures reported by the Japanese just did not add up! They did not square with the intelligence reports or what was learned from interviewing former American POWs. An accurate accounting required a reexamination of the Japanese records prepared by the Japanese Government Prisoner of War Information Bureau, Tokyo, and the use of information provided by former POWs who maintained lists of casualties. It was a daunting job to collect and manually compile and code the POW "death lists" and punch the IBM cards.

The POW accounting effort ended November 15, 1947, when the "death lists of Prisoners of War of Allied nationalities who died on route during the transfer from the Philippines to Japan Proper aboard the Japanese Prisoner of War Transport ships, the Oryoku Maru, the Enoura Maru, and the Brazil Maru" were approved. A supplemental list contained twenty-one names, including the sixteen names of those who died "During Transportation From Olongapo to San Fernando, P.I., December 1944."

In his foreword to the "death lists," Henry T. Omachi wrote that, following an examination of the records held by the Japanese "and a conference with the wartime employees of the Bureau," it was determined "that the information reported by the Bureau during World War II through the International Red Cross Committee to the various Allied governments concerned, pertaining to the casualties incurred during this transfer, was incomplete and misleading."

This was "evidenced by the affidavits executed by surviving prisoners of war and by Japanese records themselves, indicating that many of the deaths actually took place aboard the Enoura Maru and the Brazil Maru as well and that the dates of death ranged from December 1944 through January 1945."

To obtain a final accounting, the Adjutant General's Office, Machine Records Branch, meticulously went through the "death lists," writing "B" and the date of death in the margin beside the names of those who died aboard the Brazil Maru. "E" indicated death aboard Enoura Maru, and "XDS" followed by "23 Dec" marked the deaths of those who died "During Transportation From Olongapo to San Fernando, P.I., December 1944."

Scattered throughout the collection are penciled notations, "Dec Sinking." "DS" was probably combined with the first letters of the transport names, or "X" for crossing, to create the codes BDS, EDS, XDS, and ODS (Oryoku Maru). These codes were punched into the IBM cards of those who died aboard these ships or during the crossing. They were then fed through the compilers and tabulators of the time to yield the final totals.

n/a=not available

* from World War II Prisoner of War Data File, retrieved from AAD

The story of the men who entered the holds of hell began in the battle of the Philippines and ended in a struggle for the truth. From the ships' first appearances in the wireless communications of the Japanese, their physical descriptions, destinations, convoys, and sometimes, their cargoes were known. There is little evidence of advanced information that POWs were aboard.

Individual messages were frequently garbled. Reception was sometimes poor, and decryption, translation, and interpretation flawed. What was interpreted by one intelligence unit as "troops" was interpreted by another as "prisoners of war." In the context of the many other convoy and transport messages, as well as the cargo histories of the "death" ships, there was ample evidence suggesting these ships typically carried munitions and reinforcements. Given, too, that the "hell ships" were unmarked, there was no way U.S. Navy aircraft and submarines could know Allied prisoners of war were aboard.

"Magic" and Military Intelligence Division summaries of information taken from intercepts, captured material, and prisoner interviews confirmed casualty figures from Shinyo Maru and Arisan Maru but raised great doubts about those submitted by the Japanese for Oryoku Maru. Since the source of this information was Top Secret ULTRA and an exact, name-by-name accounting was required for servicemen's families, an intensive effort was made over several years to obtain complete lists and identify those who died on board Oryoku Maru, during transport from Olongapo to San Fernando, and aboard the Brazil Maru and Enoura Maru.

In the end, early IBM punch cards and machines were required to unravel the mystery of the deaths of those who stepped into hell that distant December day.

Lee A. Gladwin is an archivist with the Archival Services Branch of the Center for Electronic Records, National Archives and Records Administration. His particular areas of study are Alan Turing, Bletchley Park and World War II codebreaking. His introductions to two of Alan Turing's Enigma-related documents discovered at NARA were published in recent issues of Cryptologia. His paper "Alan M. Turing's Contributions to Co-operation Between the UK and US" will appear in Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker (Holland: Springer-Verlag, 2003).

Note on Sources

Selected Primary Sources

"Death Lists," POW diaries, and correspondence of the Director, American Prisoner of War Information Bureau, Office of the Provost Marshal General, may be found in Record Group 389, Records of the Office of the Provost Marshal General, General Subject File, 1942–1946, American POW Information Bureau Records Branch, Entry 460A, Sinkings, Box 2276.

Decrypted Japanese ("Orange") intercepts, indexed by ship's name, may be found in Record Group 38, Records of the Chief of Naval Operations, Translations of Intercepted Enemy Radio Traffic and Miscellaneous World War II Documentation, 1940–1945, Entry 344, Box 1299.

Joint Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Area Summaries of ULTRA Traffic, September 11–December 31, 1944, are located in Record Group 457, Records of the National Security Agency/Central Security Office, Intelligence Reports from U.S. Joint Services and Other Government Agencies, December 1941–October 1948, SRMD 5-7 (Part IV), Entry 9024, Box 2.

All of the above are located at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Useful secondary sources include Frank Cain, "Signals Intelligence in Australia during the Pacific War," Intelligence and National Security 14 (Spring 1999); Lee A. Gladwin, "Top Secret: Recovering and Breaking the U.S. Army and Army Air Order of Battle Codes," 1941–1945, Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 32 (Fall 2000): 174–182; E. Bartlett Kerr, Surrender & Survival: The Experience of American POWs in the Pacific, 1941–1945 (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1985); Gregory Michno, Death on the Hellships: Prisoners at Sea in the Pacific War (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2001).

For much greater detail concerning the encoding and enciphering of messages, see Edward J. Drea, MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War against Japan, 1942–1945 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992), and Maurice Wiles, "Japanese Military Codes" in F. H. Hinsley and Alan Stripp, eds., Codebreakers: The Inside Story of Bletchley Park (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

For extensive treatment of Japanese codes, see Michael Smith, The Emperor's Codes: The Breaking of Japan's Secret Ciphers (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2000) and W. J. Holmes, Double-Edged Secrets: U.S. Naval Intelligence Operations in the Pacific during World War II (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1979).

[Amended on Feb. 20, 2024:

A list of names Allied prisoners of war aboard the Oryoku Maru can be found at James W. Erickson's Roster.]