De Smet, Dakota Territory, Little Town in the National Archives

Winter 2003, Vol. 35, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By Constance Potter

Knowing where people lived and understanding that community is as important as knowing when someone was born or died. Laura Ingalls Wilder, born in Wisconsin in 1867, wrote eight books about her childhood that describe how her pioneer family lived and traveled from Wisconsin to Indian Territory (Kansas) to Minnesota and finally in 1879 to Dakota Territory.

Wilder's "Little House" books document the story of her family and the pioneer communities where they lived. The last four books take place in De Smet, Dakota Territory (later South Dakota).

Much has been written about Wilder's books and whether her stories accurately reflect what happened. Wilder did not claim to be writing history but rather a story of her life as a little girl and young woman on the frontier. Through federal records, some incidents can be verified, and others can be reinterpreted.

To use the records of the National Archives, you need to know how a person or community could have interacted with the federal government. The federal government distributes public land, prepares annual reports, studies the weather, and opens post offices. (NARA does not, however, keep vital statistics - birth, marriage, and death records.) Using homestead files, annual reports, climatological reports, and post offices records, you can get a broader understanding of the time and place in which a person lived. An examination of the Ingalls and Wilder families in De Smet, shows how these records may be used to fill out a family or community history.

Laura's father, Charles Philip Ingalls, moved his family to Dakota Territory in 1879, when he took a job as storekeeper, bookkeeper, and timekeeper for the Chicago and North Western Railroad. Charles was born in Allegheny County, New York, in 1836, and his wife, Caroline Quiner Ingalls, was born in 1839 in Wisconsin. They married on February 1, 1860. The Ingalls had four daughters: Mary and Laura (both born in Wisconsin), Carrie (born in Indian Territory, later Kansas), and Grace (born in Iowa).

On August 25, 1885, Laura Ingalls married Almanzo James Wilder. Born in New York in 1857, Almanzo moved with his older brother, Royal, and sister, Eliza Jane, to Dakota Territory in 1879. All three homesteaded, and Eliza Jane taught school. Laura Ingalls Wilder described Almanzo's boyhood in Farmer Boy.

Homesteading

Charles Ingalls and the Wilders all filed for homesteads near De Smet. Under the Homestead Act of 1862 (12 Stat. 392), citizens and those who had filed their intention to become citizens were given 160 acres of land in the public domain if they fulfilled certain conditions. In general, an applicant had to build a home on the land, cultivate the land, and reside there for five years.

The National Archives holds the homestead files, which comprise the applications, proofs, and final certificates. To locate individual land records, you need to know the legal description of the land and the state office at the time of the transaction. (State offices can change.) This information is available from the clerk of the county court where the land is located or the Bureau of Land Management web site.

The amount of detailed information in case files varies from file to file. While Charles P. Ingalls's file contains only the basic details, Eliza Wilder's file includes two letters written in 1886 that detail her experiences as a homesteader.

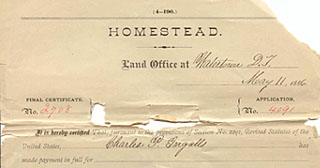

Charles Philip Ingalls

Charles Ingalls filed for his homestead at the Land Office in Brookings, Dakota Territory, on February 19, 1880 (Sec. 3, Township 110 N, Range 56 W, Kingsbury Co., D.T.). In his testimony of claimant, Ingalls swore "I am the head of a family consisting of a wife and four children and a citizen of the United States." The names of his wife and daughters are not listed.

On April 30, 1886, the Kingsbury County News published Charles P. Ingalls's notice of intention to make final proof in support of his claims. Among his witnesses was Royal Wilder, Almanzo's older brother.

In his testimony of claimant filed in May 1886, Ingalls testified that by May 1880 he had built a 16' x 24' frame barn that dwarfed the original 14' x 20' house. Ingalls had added a one-story 12' x 16' addition. Apple and plumb trees provided food and shade. He estimated the homestead's total value at $1,000. Ingalls further testified that he had never made another homestead entry and that he was a "native born citizen."

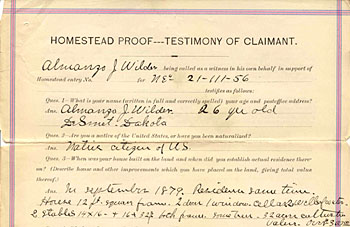

Almanzo James Wilder

Almanzo Wilder came to De Smet to homestead along with his older brother, Royal, and sister, Eliza Jane. In The Long Winter, Laura writes, "When he came West, Almanzo was nineteen years old. But that was a secret because he had taken a homestead claim, and according to law a man must be twenty-one to do that." (p. 99)

In his homestead proof dated September 12, 1884, Almanzo declared that he was twenty-six. On the same date, O. C. Sheldon, who had known Wilder for five years, certified that Almanzo was "over 21 years old." This is consistent with his entry on the 1880 census, where he is listed as twenty-two years old. Almanzo came to Dakota Territory to homestead, and there are no inconsistencies about his age in any of the public records found in the National Archives.

In Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend (p. 64), John C. Miller writes that Laura changed her husband's age to minimize the ten-year difference in their ages. Miller also notes that Laura also reduced the age "to create the artificial drama of having him too young under the law to take out a homestead claim."

In 1884, Almanzo lived in 12' x 12' frame house with two doors, one window, and a cellar, while his stock lived in two stables, one 14' x 16', and the other 16' x 32'. That same year, Almanzo filed notice of his intention to make final proof in support of his claim (Sec. 21, Township 111 N, Range 56W, Kingsbury Co., D.T.). A. J. Sheldon, O. C. Sheldon, R. A. Boast, and C. P. Ingalls witnessed his intention.

Eliza Jane Wilder

Eliza Jane Wilder, Almanzo's sister, filed a homestead claim and taught at De Smet's one-room school. Eliza Jane's file describes homesteading conditions in the Dakotas and the difficulties single women had in proving a homestead (Sec. 28, Township 111 N., Range 56 W, Kingsbury Co., D.T.).

A minor, and sometimes abrasive, character in the "Little House" books, Eliza Jane Wilder comes through as a determined woman, often overextended by the strains of proving up a homestead and teaching. Wilder was born in Malone, New York, in 1850, seven years before her brother Almanzo, and attended the Franklin Academy there. Trained as a teacher, she first taught school at nineteen. In the 1870s, the family moved to Minnesota.

In April 1879 she moved to Dakota Territory to teach and homestead. In August she filed for her homestead in Yankton, the territorial capitol. In an 1886 letter to the Department of Interior's Land Commissioner, Wilder describes her farm and living conditions over several years.

My home was growing in beauty and desirability. I spent $100.00 on improvements on my house. Twas a year of hard work and very few of the young men in our eastern states would or could have done the work I did that year or endured the hardships & exposure to intense heat in summer & cold in winter. I worked out of doors 5 hours the 3rd day of Jan 1884 when mercury was frozen and spirit therm indicated 45° below zero. A strong winder blowing and sleet falling that cut like a knife. I remembered the days for it was my birthday and will I think I was blue and discouraged.

Weather Records and the Long Winter, 1880–1881

The winter of 1880–1881 was one of the worst on record in the Dakotas. The first blizzard, which raged for three days, came in early October; by Christmas the trains had stopped running. By spring,

the blizzard winds had blown earth from the fields where the sod was broken, and had mixed it with snow packed so tightly in the railroad cuts that snowplows could not move it. The icy snow could not melt because of the earth mixed with it, and men with picks were digging it out inch by inch. It was slow work because in many big cuts they must dig down twenty feet to the steel rails.

April went slowly by. There was no food in the town except for the little wheat left from the sixty bushels that young Mr. Wilder and Cap had brought in the last week of February. Every day Ma made a smaller loaf and still the train did not come. (The Long Winter, p. 316)

Eliza Jane's letter to the land commissioner supports Laura's description of the "Long Winter."

In Oct. a blizzard came and for three days we could not see an object ten ft from us. The R.R. were blocked for ten days. Snow in the cuts being packed like ice. After the storm ceased I went to town for flour and coal.

Our merchants had none. A carload of flour would have been there in a few hours when blockaded.

My mother took me home with her for the winter. But I left everything except my wardrobe in Dakota not expecting to be gone more than two or three months. But storm followed storm. After the middle of December I think no trains reached De Smet until May.

Many families were reported frozen to death and others lived wholly on turnips, some on wheat ground in a coffee mill.

The small coffee mill used to grind wheat became large in the life of the Ingalls family.

[Ma] sat down, placed the square box between her knees to hold it firmly, and began turning the handle around and around. The mill gave out its grinding noise.

"Can you make bread of that?" asked Pa.

"Of course I can," Ma replied. "But we must keep the mill grinding if I'm to have enough to make a loaf for dinner." (The Long Winter, p. 194)

The family continued to grind wheat throughout the rest of that long, long winter.

Weather records are not frequently used in genealogical research, but they can help explain why families may have been forced to move because of drought or floods. The Climatological Records of the Weather Bureau, 1819–1892 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T907, roll 475) include monthly reports that are organized by weather station and then by month and day. The reports indicate barometric readings; the monthly range of the mean, low, and high temperatures; the total rainfall or snow melted; the depth of unmelted snow lying on the ground at the end of the month; and the total number of days on which snow or rain fell.

The records for De Smet do not begin until February 1889. To get an idea of the conditions during the "Long Winter," the Yankton reports are the most useful. These records show the following range of temperatures for the winter of 1880 to 1881:

Tornadoes often sweep through the plains in late summer and early fall. Eliza Jane wrote about a tornado in August 1882:

In August I was caught in a storm of wind, rain, and hail so severe the Catholic church was crushed[.] the town hall and other buildings moved from their foundation. Gardens were destroyed[,] small grain badly injured. My hand and arm were blackened where the hail struck them.

The same tornado is described in These Happy Golden Years.

One family had nothing but the clothes they wore, and one quilt that his wife had snatched to wrap around the baby. . . .

The homesteader and his family had been gathering boards and bits of lumber that the storm had dropped, and he was figuring how much more he would have to get to build them some kind of shelter. . . . [W]hile they stood considering this, one of the children noticed a small dark object high in the clear sky overhead. It did not look like a bird, but it appeared to be growing larger. They all watched it. For some time it fell slowly towards them, and they saw that it was a door. . . . It was the front door of this man's vanished claim shanty. It was in perfect condition, not injured at all, not even scratched.

"I never saw a man more chirked up than he was," said Pa. "Now he doesn't have to buy a door for his new shanty. It even came back with the hinges on it." (These Happy Golden Years, pp. 257–258.)

Post Office Records

Just as the "Long Winter" becomes a major character in the books, so too does the little town of De Smet. Ingalls describes the budding little town:

Suddenly, there on the brown prairie where nothing had been before, was the town. In two weeks, all along Main Street the unpainted new buildings pushed up their thin false fronts, two stories high and square on top. Behind the false fronts the buildings squatted under their partly shingled, sloping roofs. Strangers were already living there; smoke blew gray from the stovepipes, and glass windows glinted in the sunshine. (By the Shores of Silver Lake, p. 242.)

After the railroads came, many people moved into the area to homestead. Among the necessary services were post offices. A town applied to the Post Office Department, submitting forms and letters describing why they wanted a post office and where it would be located. These records are found in Post Office Department Reports of Site Locations (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1126, roll 543) Using these records, one can trace the growth in the early 1880s of this small railroad town surrounded by public lands.

On February 24, 1880, George H. Bryan requested that a post office be established in De Smet, which was described in the application as a railroad town on a plateau. Although Bryan noted that there were only fifty people in the town, he wrote that the post office would serve five hundred. The 1880 census describes Mr. Bryan as a builder, and in 1880 he took the census for De Smet. Less than a month later, on March 15, 1880, he submitted another request for a post office. By now, he noted, three hundred people were living in the town.

By the summer of 1884, Laura

had quite forgotten that she had ever disliked the town. It was bright and brisk this morning. . . . In the two blocks there were only two vacant lots on the west side of the street now, and some of the stores were painted, white or gray. . . . Everywhere was the stir and bustle of morning. . . . Doors slammed; hens cackled, and horses whinnied in the stables. (These Happy Golden Years, p. 27)

This article describes only some of the federal records that tell about the Ingalls and Wilder families. Federal population and nonpopulation censuses as well as military records also provide information about the family and De Smet, South Dakota. Federal records such as these may exist for your family and the town or city where they lived.

Constance Potter is a reference archivist specializing in federal records of genealogical interest held at the National Archives and Records Administration.

Note on Sources

The homestead files are from the Records of the Bureau of Land Management (Record Group 49). The legal descriptions of the files discussed in the article are in parenthesis within the text. The historical land office for these homesteads was Watertown, S.D. The current land office is Montana.

To request copies of land entry files such as credit, cash, homestead, and mineral files, use NATF Form 84, National Archives Order for Copies of Land Entry Files. To request a copy of the form, call 1-866-272-6272 or send an e-mail to inquire@nara.gov.

The success of a land entry search depends on the completeness and accuracy of the information you provide on the form. Depending on the date and state for the land entry file you request, we may need additional information to find it. This is explained in detail on the form.

The Post Office Department Reports of Site Locations (M1126) are from the Records of the Post Office Department (Record Group 28), which are available on microfilm in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and in NARA's regional records services facilities.

The Climatological Records of the Weather Bureau, 1819–1892 (T907) are from the Records of the Weather Bureau (Record Group 27). They are available on microfilm the National Archives at College Park.

Laura Ingalls Wilder, By the Shore of Silver Lake (1939), The Long Winter (1940), Little Town on the Prairie (1941), These Happy Golden Years (1943, paperback 1971).

The author would like to thank George Briscoe, Katherine Coram, Dennis Edelin, Meg Hacker, MaryBeth Linne, Virginia E. Potter, Reginald Washington, and Thomas E. Weir, Jr., for their help.