A Boy Who Would Be President

Harry Truman at School, 1892–1901

Fall 2004, Vol. 36, No. 3

By Raymond H. Geselbracht

Harry Truman has been the subject of a massive amount of historical writing in recent decades, including three fine biographies, totaling more than two thousand pages, published in the 1990s. But despite all this attention from historians, surprisingly little is known about an important aspect of a man whose stature as President is based to an important degree on the kind of person he was, or as is usually said today, on his character.

We do not really know much about his education—his formal education, his nine years spent in Independence, Missouri, public schools. We know what books he read and learned from on his own, away from school; we know he greatly liked and admired his teachers; we know he was a good boy and young man during his school days. But our imagination has not been able go very far toward seeing that boy and young man sitting in the classroom, doing his lessons, taking tests, growing up and developing ideas about life.

Important new documentation of Truman's schooling has recently been discovered—two ledgers that record his attendance and his grades at Noland School for the first and second grade—and two of his high school English theme books were recently made available for research by members of Truman's family. These documents reveal some things that have not been known before about the schooling of a little boy who, fifty years later, became President of the United States at one of the most perilous and formative times in the country's history.

Truman's first serious biographer, his former press secretary Jonathan Daniels, said that all Truman's school records were destroyed in a fire in 1938. President Truman was probably the source of this information, and he very likely got it from one of his former teachers, Ardelia Hardin Palmer. Despite the fire—which burned down Independence High School and the school district's administrative offices (in 1939, not 1938)—not all of Truman's records were lost.

In the summer of 2000, this author discovered that two Noland School ledgers containing grade and attendance records for Harry Truman from the 1890s had survived the 1939 fire. The Independence School District very generously donated the two ledgers to the Harry S. Truman Library.

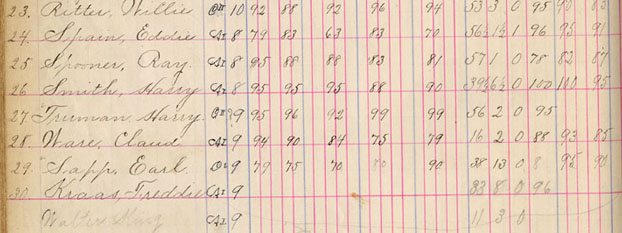

Each ledger contains the record of the attendance and grades of students—probably students in a single Noland School classroom—for several years. The students are listed in alphabetical order, the boys and girls sometimes listed separately. The records indicate that the school year was divided into three terms, running from September to early December, early December to early March, and early March to late May. The terms are designated in the ledgers by letters: c being the first term, b the second, and a the third.

The 1892–1893 school year, Harry's first-grade year, began on September 13. For some reason Harry's mother, Martha Ellen Truman, didn't send him to school until October 17. His teacher, Mira Ewin, entered his name in her ledger, "Harry Truemann." He was eight years old, or, more precisely, eight years and five months old, which made him probably about six months older than the average student in Miss Ewin's first grade. The ages of the first graders ranged from six to thirteen years old.

Harry was a very punctual and dependable student and apparently a good, well-behaved boy. After starting school five weeks late, he didn't miss a day for the rest of the year, and he was never tardy. His "deportment" grade was a perfect 100 for all three terms, a distinction shared by only ten of his classmates. John Anderson and Martha Ellen Truman must have insisted that their little boy keep to a very high standard of behavior.

In the first term, Miss Ewin gave Harry the highest possible grades in every subject. They were a little lower in the second term, but still among the highest given in the class, and they rose to near perfect in the third term. Miss Ewin gave him the highest possible grades in the third term in spelling, reading, language, and numbers.

When Miss Ewin was asked about her famous pupil in 1947, she said, "I never had to reprimand him a single time. He just smiled his way along. [He] was a very studious boy. When other boys were out playing ball he was reading." One of Harry's classmates in Miss Ewin's first-grade class remembered many years later that "he was always studious. I admired this in him."

Harry began second grade at Noland School in September 1893. His teacher was Minnie Ward. This was a fine term for Harry. His excellent attendance record was spoiled only by two absences, on November 9 and 10. Maybe he had a cold. He was present for all the other fifty-six days and never tardy. Of all Miss Ward's students that term, Harry's grades were the best. Harry averaged 96 for the five major subjects, compared with an average 88 for the other students in the class. He got the highest grades in the class in reading, language, and numbers, and he narrowly nudged out two girls to be the best student in the class.

Harry started the second term of the second grade on December 12, 1893, and was present every school day through January 19, 1894. Over the weekend of January 20–21, though, he contracted diphtheria. He had a very serious case. After starting to recover, he suffered a relapse, and he became paralyzed for perhaps a few months. His parents pushed him around in a baby carriage or laid him on the floor and gave him a book to read. According to his sister, Mary Jane, he developed his lifelong love of reading during the months when he could not walk. He missed the rest of the school year, and he never went back to Noland School.

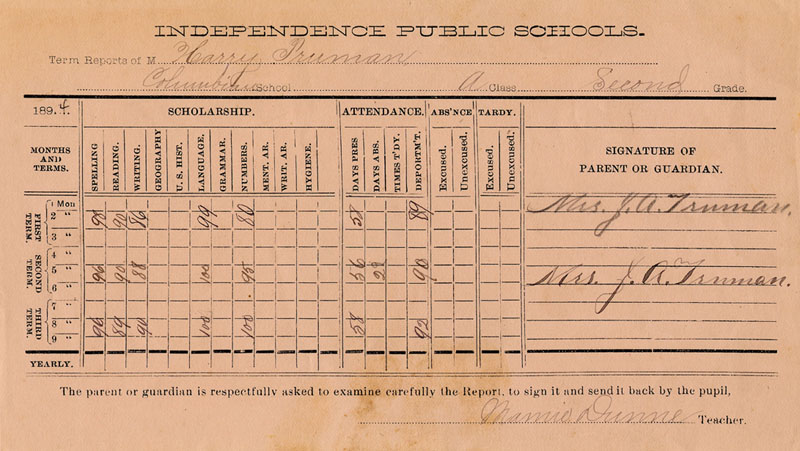

According to an account of his schooling that Truman wrote in 1951 or 1952, he went to summer school after recovering from diphtheria, and the next fall he went to Columbian School. He skipped third grade, he says, and started the year as a fourth grader. This year at Columbian School provides the last opportunity to learn in some detail what kind of grades Harry got. None of his school records for this year have survived, but his report card has. It is a problematic document, though. Harry's teacher, Mamie Dunne, has written on the card his name and the name of the school, and the grade level—"Second." According to Truman's account, it should say "Fourth."

Miss Dunne noted something else on this card, though, which suggests it might be both a second and a fourth grade card. On the line for "Class"—or term—she has written "A." This is the last term of the grade, which would be exactly right for Harry Truman if in summer school he made up, as one would expect he would, only a single term—that is, the b term of second grade. If this is true, then Harry started at Columbian School in the fall of 1894 in grade 2a, exactly as Miss Dunne recorded at the beginning of the school year, on a card intended to record grades for the entire year.

But what of Truman's claim that he skipped third grade and started at Columbian School in the fourth grade? Perhaps Truman's recollection on this point was only partly right. He actually writes in his autobiographical memorandum that he went to summer school after he recovered from diphtheria "to catch up to the Third Grade," but then, a few lines later, he says he "went back to school and skipped the Third Grade." Perhaps the first part of this memory is as true as the second. Perhaps he actually started in the fall of 1894 in grade 2a, as his report card says, and skipped terms during the year. Perhaps by the end of the year he was, as he later claimed, in fourth grade. Another report card that has survived, for another student, suggests that this might be what happened. It is Bess Wallace's card from the fourth grade, the only one of her cards to survive. According to the notes her teacher wrote on the card, Bess started the year in grade 4c, but then she skipped to 4a in the second term, and to 5b in the third term. Since term skipping was clearly practiced in the Independence schools at this time, perhaps Harry Truman skipped ahead during the 1894–1895 year, putting him somewhere in the fourth grade by the end of the year. This would explain what one sees on Harry's report card, and it allows Truman's memory on this point to be seen as at least vaguely true.

In any event, the card records things about Harry the schoolboy very much like what the Noland School ledgers reveal. He was seldom absent during the year and never tardy. His grades in the first term were a little low for him, but one would expect that his illness and his long absence from school the prior spring might have put him a little off his normal form. His grades rose in the second term, though, and again in the third. His final set of grades includes two perfect 100s, in language and numbers, a 96 in spelling, a 90 in writing, and an 89 in reading. His deportment grades hovered around 90 all year, a drop from his first two years, which might suggest that he had developed by this time what would become a lifelong love of talking to people.

Unless other new documents appear, Truman's schooling in grades 5 through 7 must remain obscure. He probably went to Columbian School through the end of December 1895, when he was midway through fifth grade. Then, around the first of the year, his family moved, and he transferred to Ott School. This was in the long run one of the most important things that ever happened to Harry Truman, because Bess Wallace went to Ott School too. She was a year younger than Harry, but they were in the same grade nonetheless. Bess sat right behind Harry. It was probably beginning at this time that Harry began to develop his incredible determination to love no woman in the world other than Bess Wallace. Beyond this sense that romance was in the bud at this time, Harry's days in the fifth through seventh grades are featureless. He apparently returned to Columbian School for seventh grade, perhaps because Ott School, burdened with both an elementary or "ward" school downstairs and the high school upstairs, was overcrowded.

For eighth grade, the first year of high school, Harry moved to the upper floor of Ott School, where five or six teachers ran what was called simply "the High School." As Harry went through his first high school year, a new high school was being built near Bess's grandparents' house, on the corner of Maple Avenue and Pleasant Street. The building was completed in the spring of 1899, and Harry may have started school there in the fall, or possibly in January 1900. Truman remembered that the high school moved to Columbian School for half a year, but it is not clear whether he means during his eighth- or ninth-grade year.

Among Harry's classmates was Charles G. Ross, who would forty-four years later become Truman's White House press secretary. Charlie was probably the best student in the class. Truman later remembered of him that "teachers and students alike acclaimed him as the best all-round scholar our school had produced." Truman also remembered that academically "I was along about the middle."

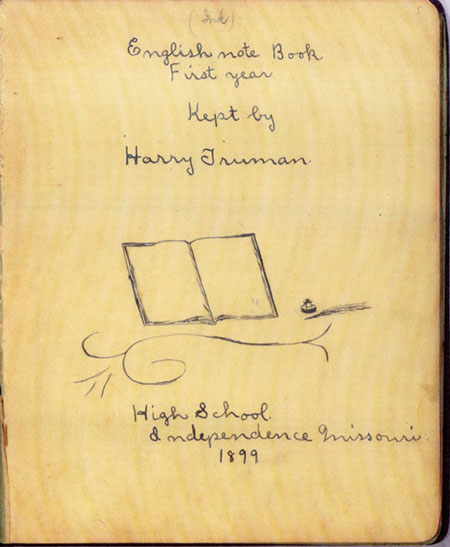

No grading books or report cards survive to indicate what kind of student Harry was in high school, but two very revealing theme books have survived—one from his eighth grade or freshman year, and one from his tenth grade or senior year. In 2000, Truman's niece allowed the Truman Library to copy them and make them available for research.

The eighth-grade book, prepared under the guidance of Miss Matilda Brown, Harry's and Charlie's English teacher during all three of their high school grades, reminds one why Harry once wrote to Bess that "the English language so far as spelling goes was created by Satan I am sure." The short essays in the book (including some on loose pieces of paper) include such stumbles as "anaversery," "bond fires," "conserned," "comming," "miror," "principle thing," "natoin," "allmost," "sophamore," "coppies," "acuratly," and "beatiful." But it also contains several passages that suggest the development of an independent habit of mind and a personal philosophy of life.

At the end of one essay, Harry writes, "We should . . . learn to judge for ourselves the things that we see and learn from some one's point of view." In his essay on James Fenimore Cooper, he writes that the Leatherstocking novels "are interesting and famous, but [the] sentences are too long." Cooper's sea tales are interesting too, "but I think they have too many words in them." In his essay on John Greenleaf Whittier, the young student, who in his long life to come would form all his truly intimate bonds with women, concludes that "Whittier was happy . . . in all but one thing, and that was he was a bachelor." In his meditation on "Courage," Harry writes that "a true heart[,] a strong mind and a great deal of courage and I think a man will get through the world," which describes fairly well the attitude he would try to bring to his presidency many years later.

The English theme book from Harry's tenth-grade year is especially interesting, both for its content and because it can be juxtaposed with Charlie Ross's theme book for that same class. Besides being the best student in the class and a future White House press secretary, Charlie was also a future Pulitzer Prize–winning correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His essays provide a contemporary benchmark of student excellence against which Harry's essays can be compared. Miss Brown gave Charlie's book a perfect grade of 100, and she gave Charlie a note that gushed, "Your notebook certainly illustrates your motto 'Excelsior.'"

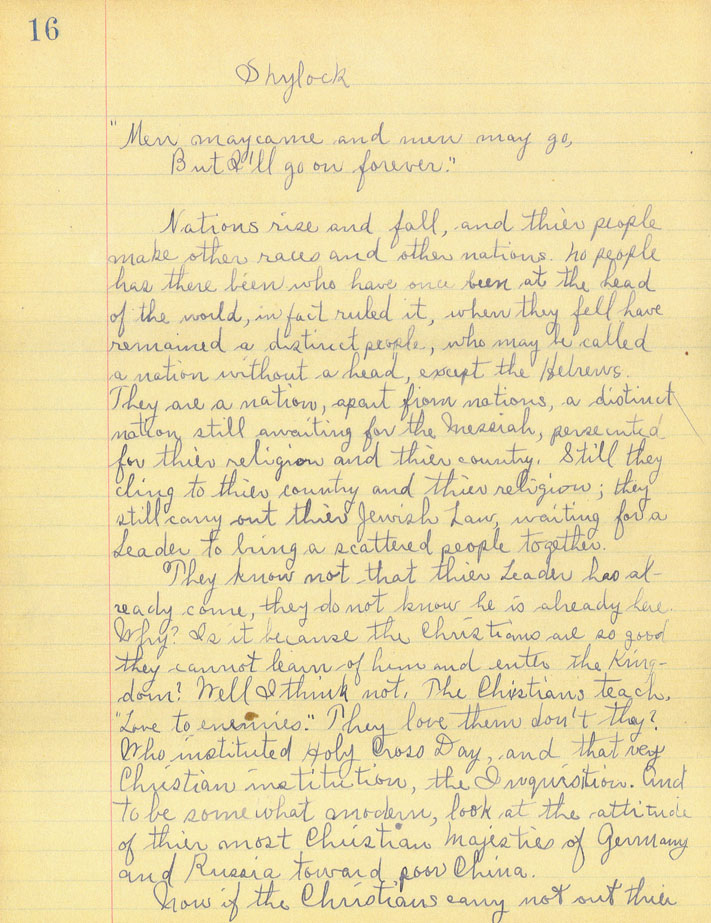

Most of Harry's and Charlie's tenth-grade English theme books are devoted to an analysis of the characters in Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice. Charlie writes more than twice as much as Harry about each character, and his prose is more elaborate and refined than Harry's. Charlie's writing is remarkably sophisticated for a boy of fifteen; it clearly reaches and exceeds some standard for student exposition that was set by Miss Brown and many others like her for the students of the age. In this sense, it is not remarkable, though always excellent. Charlie could compose, as Harry certainly never could, an extended and elegant simile comparing friendship to music. "A real friendship may be likened to an exquisite symphony," he writes, "the tones of which, though in contrast, are inwardly related, forming one harmonious whole. There are the sprightly, the slow; the sad, the joyous; the playful, the stately; all mingling in one sweet burst of melody, rising wave on wave to charm the ear and entrance the soul of the hearer." The well-cadenced phrases that comprise the simile build and build until they reach a climax as Charlie relates that those who make music are "freed from the cumbrance of the flesh, and soar to heights not reached by mortal man. Such is the power of music," Charlie concludes, "such also is the power of friendship." Harry Truman was not capable of writing like this.

Charlie's essays on the five main characters of The Merchant of Venice typically recount each character's role in the play. He makes judgments on the characters, but his judgments are usually nuanced and somewhat disembodied, rather than strongly and personally felt. He informs us that Antonio's character is centered on his love for Bassanio; he tells us too that Bassanio is capable of being both a true friend to Antonio and the lover of Portia. He describes Portia's development from capricious, independent single woman to loving and presumably dutiful wife to Bassanio. Charlie feels that Portia's "sweet surrender" to her husband is a "notable example of true womanliness."

Charlie's essay on Shylock is his longest. When discussing Antonio, Charlie had pulled back from condemning that character's anti-Semitism. He worried that if he condemned Antonio, he would be condemning as well those in turn-of-the-century Independence, including perhaps himself, who were no less prejudiced. "We cannot condemn him without condemning ourselves," he wrote, "for we have a similar case here at home in our relations with the negro. . . . Very few of us indeed at heart rise above a certain loathing of the negro." Having said this, Charlie examines Shylock's character to determine whether he was on "a lower moral plane than his enemies, the Christians." At the end of his long essay, though, Charlie concludes rather obscurely, "Shylock the oppressed is overthrown, his oppressors vindicated. Truly, the irony of Fate is past all understanding." As for Shylock's daughter, Jessica, Charlie suggests that she not be judged too harshly for abandoning her father. But, having said this, he is tempted to change his mind. Some of Jessica's actions, he says, are inexcusable. To find a way out of this muddle, he decides he will "take a lenient view of the matter and admit that 'Her beauty covereth a multitude of sins.'"

Harry's Merchant of Venice essays are shorter than Charlie's, the prose doesn't flow as smoothly, the exposition of Shakespeare's play is not as satisfactory. One feels that the standard of excellence for student performance that Miss Brown and the other teachers of her time put forward is not approached so nearly in Harry's essays as in Charlie's. In fact, there's something almost objectionable in Harry's essays. Perhaps they're not always sufficiently deferential to some spirit of the age; there's too much opinion in them, too much Harry.

If Charlie is mindful of his readers and their values and their expectations of him, Harry seems to want only to tell everyone very plainly how he feels about things. He decides that Antonio might be an ideal man. He is brave, a good Christian, warm hearted, neither haughty nor hypocritical, and he loves another human being. All this is good, and as it ought to be. But Harry is disappointed that the loved human being is another man. "If Antonio had loved a woman," he writes, "we might have had quite a romance."

He takes a very realistic attitude toward Bassanio. This imperfect character loves money, it's true, "but where," Harry asks, "is the man who doesn't like to have 'a little more than he can spend.'" Bassanio likes to have a good time, "and how can there be a good time without a woman?" Harry seems always to be thinking about a woman, a loved companion. In this case the woman is rich, and the man, Bassanio, has debts and is in need of money. This is a dangerous formula, Harry knows, but he resolves the problem with an outburst of romanticism. "Portia," he says, "was beautiful and virtuous, therefore she was worth all." And Bassanio, Harry argues, substituting force of opinion for logic, is worthy of Portia. "If someone will give a reason why he isn't," Harry challenges his reader, "I'll find two why he is." Bassanio has his faults, Harry concludes, "but who's perfect?" One can imagine Miss Brown making her way through this disturbing argument.

Harry gives almost a third of his essay on Portia to taking issue with another of Shakespeare's characters, Hamlet, who said in his play "Frailty, thy name is woman!" Harry doesn't believe women are frail. "Look over the pages of history," he insists, "and find how many a man or nation would have fallen if it hadn't been for a woman." He evokes the strength of character of Esther and Delilah and concludes, "This doesn't look as if [woman is] frail, does it? She's generally frail to a man when she has the best of him." And he adds parenthetically a bit of sentimentalism to his argument. Women, he says, "are generally more virtuous than men."

As for Portia, Harry admits that, as Charlie said too, she went from being a "proud, unbending woman" to being a presumably submissive wife. But where Charlie somewhat Platonically views this transformation as one from a doubtful, incomplete condition to a more perfect one that he calls "true womanliness," Harry more practically concludes that she changed because all of a sudden she had everything she could possibly want—"the man she loved, all the money she wanted and plenty of happiness." Anyone, he clearly believes, would change for the powerful combination of love, money, and happiness.

Harry's essay on Shylock is much different than Charlie's. Charlie spent most of his time recounting Shylock's place in the play's plot, and his problematic "irony of Fate" conclusion leaves one in doubt about what Charlie's view of Shylock in fact is. Harry doesn't bother with the plot much at all when he writes about Shylock. Instead he criticizes Christians for not following their beliefs, for not loving their enemies as they say they should do. Who, he asks, "instituted . . . that very Christian institution, the Inquisition[?] Now if the Christians carry not out their teachings, who's to carry them out? Not China, nor Turkey and surely not the Jews." Harry is sympathetic to Shylock and feels he could not have done anything differently than he did in the play. "Think of him leaving the court room[,] broken, childless, everything but killed. He said he was content to die. What else could he do?" Shylock sought to revenge himself on the people who hurt him. Harry understands this completely. "I never saw a Jew, Christian or any other man who, if he had the chance[,] wouldn't take revenge, although he may say 'Love your enemies' and a lot of other things of the same sort."

One may suspect that Miss Brown suffered some discomfort and felt some disapprobation as she read this essay of Harry Truman's. Perhaps she felt this young man might not be an ideal young man. He was certainly no Charlie Ross. Maybe, though, she suspected there was something unusual, something remarkably and eccentrically mature in Harry Truman. Maybe she suspected he might amount to something some day.

Harry feels the same kind of sympathy for Jessica, Shylock's daughter, as he does for her father. Her mother died when she was born, so she never had a mother's love, and her father did not really love her in a way that was truly meaningful to her. She had to find someone she could love and who would love her, and she did find him—Lorenzo. She stole Shylock's money to run away with her lover, and, Harry admits, this was not exactly right, but Shylock had taught her to value money above everything, so perhaps he deserved to have his money stolen. Besides, Harry concludes with empathy and compassion, Jessica had to have some money for herself and Lorenzo. "How in the world could they run of[f] without anything to run on?" Jessica is an easy character for Harry to understand. "In my opinion," he concludes, "Jes[s]ica is just a common woman who did what anyone would do in her place."

A well-formed personality, if one without much academic polish, emerges with some clarity from Harry's Merchant of Venice essays. Harry Truman the young man is original, and one senses he enjoys being original, and he's somewhat objectionable too. He has some of his own views about people and things, and perhaps those views are not what one would hear from the teachers or the preachers of the time.

Harry's originality is founded very solidly in insights about what people are really like, as opposed to what they are supposed to be like, and about the lives they really lead, as opposed to the lives they're supposed to lead. People are supposed to be good, and sometimes they are, but sometimes they're not so good, and maybe, Harry feels, that's the only way things can realistically be. People don't always live up to their ideals, and then, plainly said, they're hypocrites, and perhaps people who suffer hurt from hypocrisy have the right to respond in certain less than ideal ways. And life shouldn't be based completely on ideals anyway. People like to have fun, to have some money and some friends to have some fun with, and, very importantly and specially, Harry believes, everyone needs to have a beautiful and loved woman, or handsome and loved man, as one's companion.

All these things are part of humanity's real life. Human beings are as they are, not perfect, and the only sensible attitude to have toward them, and toward oneself, is one of compassion and hence of tolerance. This is the homegrown philosophy of life one finds in Harry Truman's Merchant of Venice essays, written during his senior year in high school, when he was sixteen or seventeen years old. Miss Brown gave this remarkable collection of writings a grade of 90, with no comment.

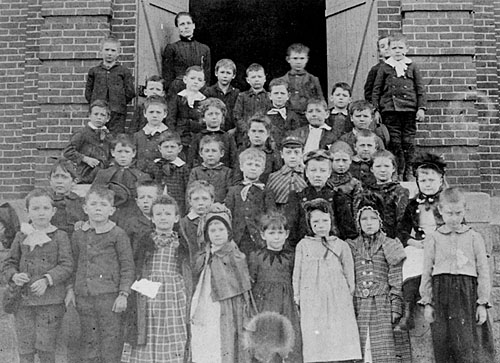

Harry Truman and his classmates graduated from Independence High School in May 1901. The students posed for photographs on the school's front steps, underneath a large, arched stained glass window that proclaimed, in Latin, "Youth the Hope of the World." About this time, Truman's father had lost or was losing virtually everything he had in speculations in grain futures. Harry could not go to college. He went to commercial school for about six months, and then he went to work to help support his family. Except for some night school classes he took twenty years later, Harry Truman's formal schooling was over.

The schoolboy always remained in the man Harry Truman grew to be. When he became President of the United States on April 12, 1945, he was—to some degree, in some important ways—the same person as he had been when he was a boy in Independence, many years before. He had certainly learned and changed in the passing years, but one can feel in the schoolboy many of the same beliefs and qualities of character that inhered in the President and helped to shape the policies of his administration. He was still the good boy in Miss Ewin's and Miss Ward's classes who was never late, worked hard, behaved well to everyone, and wanted everyone to like him; and he was still the young man in Miss Brown's English class who understood that real life and real people were not always what they were supposed to be, ideally, and that compassion and tolerance were the right response to this less than perfect reality.

Harry Truman the schoolboy and Harry Truman the President believed that ordinary people should have the opportunity to find their own real-life happiness in their own way. This is true for Shylock the Jew and his daughter, Jessica, or for the Jewish people in Europe and Palestine following World War II; for Bassanio the ruined merchant or for the struggling people of Western Europe after World War II; and for those Americans who had suffered, like Shylock, from the hypocrisy of those who espoused ideals they did not practice. All these people deserved their fair deal, their Marshall Plan, their civil rights, or maybe, if the situation required it, their own place in the world.

All the most important policy initiatives of Truman's presidency had their origins in some important way in the fundamental personal makeup that we call his character; and this essential character of Harry S. Truman's was to some degree formed by, and to a much greater degree evident during—even if only in the brief but bright glimpses the limited documentation allows—his nine years as a schoolboy in Independence, Missouri, from 1892 to 1901. Many years later, from 1945 to 1953, the content of that character entered into the country's life and became part of American history.

Raymond H. Geselbracht is Special Assistant to the Director at the Harry S. Truman Library. He has published several articles on historical and archival subjects, including Truman's relationship with the Marx brothers, his love of playing poker, and the courtship and marriage of Harry and Bess Truman. He has also published a map showing places in the Kansas City area that had special importance to Truman.

Note on Sources

All of the documents cited are in the holdings of the Harry S. Truman Library. The Noland School ledgers; copies of Truman's high school theme books; his autobiographical manuscript, written in 1951 or 1952; his correspondence with Ardelia Hardin Palmer about the burning of Independence High School and his position in his class; and his letter to Bess Wallace in which he writes about spelling (February 13, 1912) are in Truman's papers. Truman's and Bess Wallace's report cards are in the Miscellaneous Historical Documents Collection. Charlie Ross's high school English theme book, with Matilda Brown's "Excelsior" note interleaved, is in his papers. Ardelia Hardin Palmer's and Mary Jane Truman's oral history interviews are in the Oral History Collection. Newspapers articles describing Independence schools in Truman's time, and Mira Ewin's late recollections of her famous pupil are in the Vertical File. Jonathan Daniels's biography of Truman is The Man of Independence (Philadelphia, 1950).