“Just Between You and Me”: Children’s Letters to Presidents

Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1

By Ellen Fried

Americans value the right to speak their mind—even to the highest official in the land.

Every year, the President of the United States receives thousands of letters from people who write to share their thoughts on a wide range of subjects. These correspondents extend congratulations, offer praise, pose questions, make requests, share concerns, provide suggestions, and level criticism.

Many of the letters come from children. Like other records of the presidency, children's letters are preserved among NARA's holdings, mostly in presidential libraries.

Why do children write to Presidents?

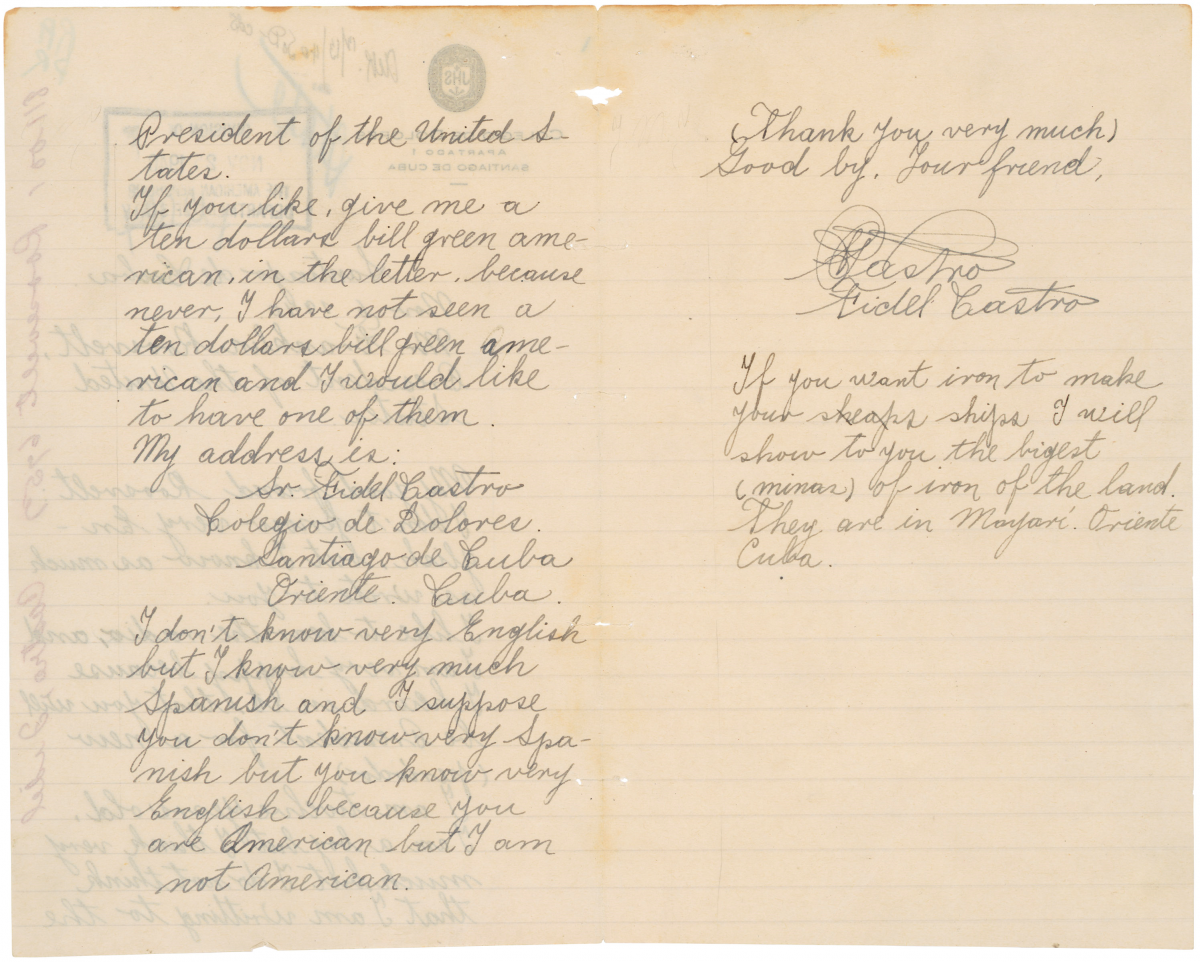

In some cases they have a favor to ask. In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt received a letter from a young student at the Colegio de Dolores school in Santiago, Cuba.

"My good friend Roosevelt," was the surprisingly informal salutation. "I am twelve years old. I am a boy but I think very much." Apparently one of the things he thought about was what he wanted from the U.S. President: "If you like, give me a ten dollars bill green american, in the letter, because never, I have not seen a ten dollars bill green american and I would like to have one of them." The letter was signed with a flourish: "Castro, Fidel Castro."

Young Castro's desire went unfulfilled; he did not receive any U.S. currency from the President. His letter is now among NARA's Department of State records.

Among NARA's holdings is another letter from a child who would grow up to be famous. In this case, the child was writing to Roosevelt not to ask for something, but to express thanks for something.This letter, too, was written in 1940. Roosevelt, an avid stamp collector, had sent a gift of stamps and a small album to the nine-year-old son of a powerful Massachusetts family. The well-mannered boy wrote back right away: "Dear Mr. President, I liked the stamps you sent me very much and the little book is very useful. I am just starting my collection and it would be great fun to see yours which mother says you have had for a long time. . . . Daddy, Mother, and all my brothers and sisters want to be remembered to you." The letter is signed, "Bobby Kennedy."

Of course, most children who write to Presidents do not grow up to be famous. They're ordinary kids, and they often write about the ordinary concerns of their lives, such as pets and illnesses and adolescent crushes. In many cases, what prompts them to write is the discovery of a commonality with the country's chief executive—a shared experience that makes these children want to reach out and make contact.

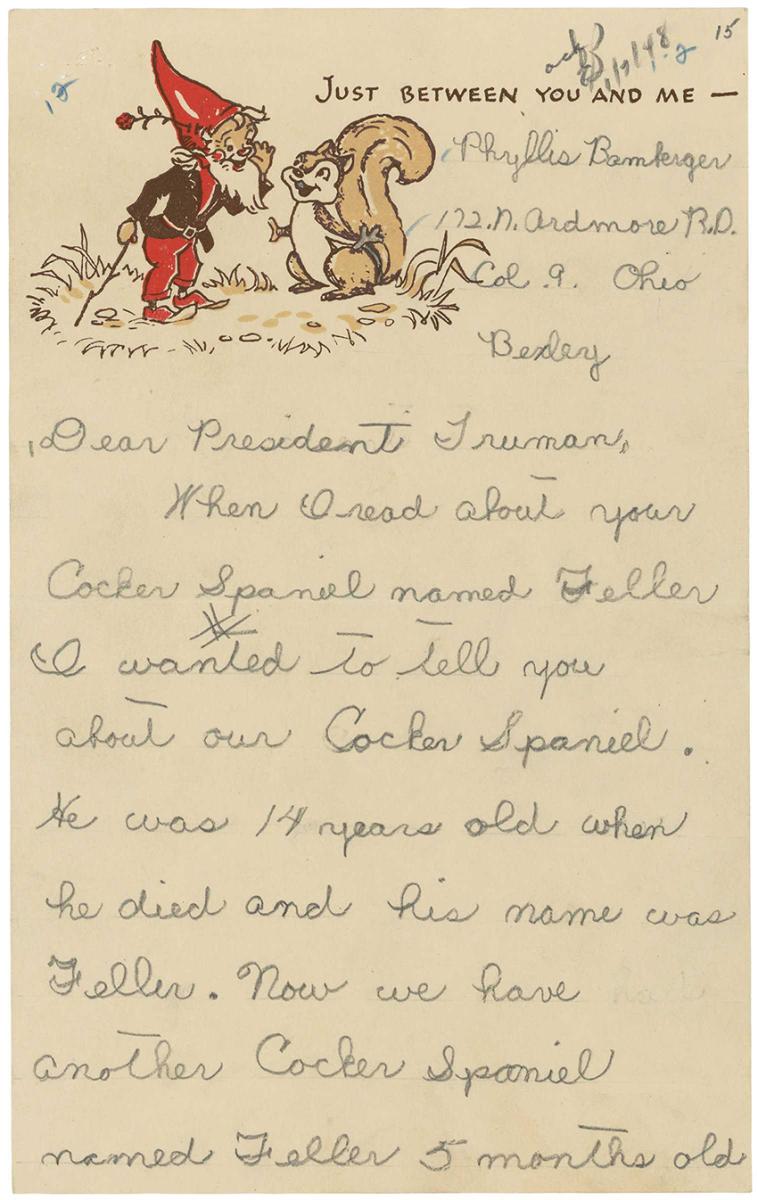

In December 1947, President Harry S. Truman received a crate containing an unsolicited gift—a cocker spaniel puppy named Feller. The news of this gift inspired a letter from Phyllis Bamberger, a young girl in Ohio. Even her stationery, featuring a picture of a leprechaun whispering to a squirrel and a caption declaring "Just Between You and Me," suggests the sense of connection the youngster felt with the President.

"Dear President Truman," Phyllis wrote, "When I read about your Cocker Spaniel named Feller, I wanted to tell you about our Cocker Spaniel. He was 14 years old when he died and his name was Feller. Now we have another Cocker Spaniel named Feller 5 months old and we have had him 4 months. I hope your dog and ours both live to be very very old."

The presidential Feller did live to be old, but it wasn't with Truman. The Trumans were not a pet-owning family, and they gave the pup to the President's personal physician. Feller eventually ended up on a farm in—coincidentally—Ohio, where he apparently spent many happy years before dying of old age.

In the summer of 1973, just as the Watergate scandal was breaking, President Richard M. Nixon contracted viral pneumonia and had to be hospitalized. His illness prompted a letter from eight-year-old John W. James III, who had just undergone the same ordeal: "Dear President Nixon, I heard you were sick with pneumonia. I just got out of the hospital yesterday with pneumonia and I hope you did not catch it from me."

Being a few days ahead of the President on the path to recovery, young John had some friendly advice to offer. "Now you be a good boy and eat your vegetables like I had too [sic]!! If you take your medicine and your shots, you'll be out in 8 days like I was." There is no record of Nixon's vegetable consumption, but his bout with pneumonia lasted eight days—exactly as long as John's.

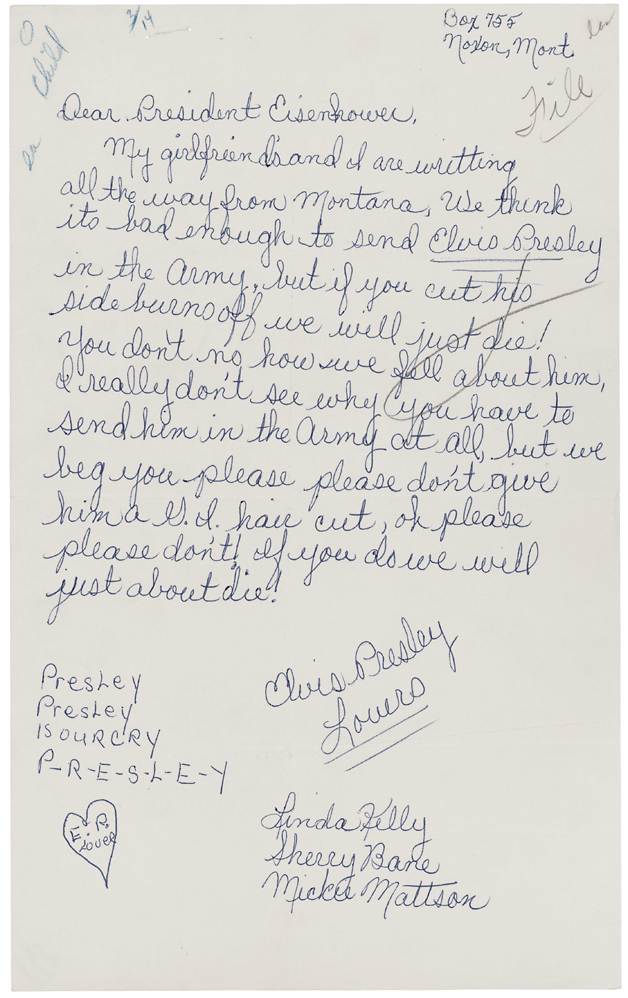

In 1958, at the height of his fame, Elvis Presley was inducted into the U.S. Army, triggering an anguished outcry from his young female fans.

Many of the letters of protest went to the draft board, but some petitioners took their plea all the way to the top. Linda Kelly and her two friends wrote to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, with a passion far more impressive than their spelling:

My girlfriend's [sic] and I are writting [sic] all the way from Montana. We think its [sic] bad enough to send Elvis Presley in the Army, but if you cut his sideburns off we will just die! You don't no [sic] how we fell [sic] about him. I really don't see why you have to send him in the Army at all, but we beg you please please don't give him a G.I. hair cut, oh please please don't! If you do we will just about die!

Photos from Elvis's army days reveal that the singer's trademark sideburns were in fact shaved off. There is no record of whether the three young ladies survived.

Some youngsters write not about their personal concerns, but about political events.

On August 9, 1974, facing impeachment for his role in the Watergate affair, President Nixon resigned from office, and Gerald R. Ford succeeded him as President. A month later, on September 8, Ford stunned the nation by announcing that he was granting Nixon "a full, free, and absolute pardon" for all crimes committed during Nixon's time in office. The decision to pardon Nixon was one of the most controversial decisions ever made by a President.

A few days afterwards, a one-line letter arrived for Ford. "Dear President Ford," it said, "I think you are half Right and half wrong."

The writer, one Anthony Ferreira, did not state his age, but his brevity, handwriting, and use of wide-ruled paper suggest that he was quite young. While his figures weren't precise—fifty-nine percent of the population actually opposed Ford's decision—this child managed to encapsulate, in a single sentence, the country's deep division over the pardon.

A longer and more sophisticated—and significantly more assertive—expression of political opinion came from an obviously older boy, Tom Oberdorfer, of Washington, D.C.

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, Ku Klux Klan members bombed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four young black girls. It was the culmination of several months of racially charged violence in the city, including bombings of black-owned homes and riots that followed the bombings. In May, President John F. Kennedy had sent federal troops to Alabama. But the troops never moved into Birmingham.

In a two-page letter, Tom expressed his opinion about that:

I heard on the news that you aren't sending troops to Birmingham. Well I think you should for this reason. Because the negroes have gone through a lot of rough treatment. . . . This has been going on since the Civil War. . . . Many of them have been killed and wounded. . . . Now they have to be armed to live. But there [sic] not going to take there [sic] weapons to church, so theres [sic] a pretty good chance that there will be another bombing this Sunday.

He offered a helpful alternative: "At least send secret service down there for church. I think that should make sense."

And he concluded somewhat ominously: "If you don't send troops send me a letter telling why. You'll hear from me again."

Sometimes, the personal and the political come together. In 1984, Andy Smith, a seventh-grader in South Carolina, wrote to President Ronald Reagan about a problem that plagues children everywhere: a messy room. Andy wrote, "Today my mother declared my bedroom a disaster area. I would like to request federal funds to hire a crew to clean up my room."

The President sent back a full-page handwritten letter brimming with tongue-in-cheek humor. "Dear Andy," he wrote. "Your application for disaster relief has been duly noted but I must point out one technical problem; the authority declaring the disaster is supposed to make the request. In this case your mother."

Then he took the opportunity to apply one of his administration's political themes to Andy's personal situation:

May I make a suggestion? This administration, believing that govt. has done many things that could better be done by volunteers at the local level, has sponsored a Private Sector Initiative Program, calling upon people to practice volunteerism in the solving of a number of local problems. Your situation appears to be a natural. I'm sure your Mother was fully justified in proclaiming your room a disaster. Therefore you are in an excellent position to launch another volunteer program to go along with the more than 3000 already underway in our nation—congratulations. Give my best regards to your Mother.

These are just a small sample of the letters written to Presidents by children. Such letters give us a glimpse into children's thoughts and often reflect the impact of current events on the youngest citizens.

In many ways, children's letters to Presidents mirror those of adults. Like adults, children cherish their right to express themselves to the leader of the country. In writing to Presidents, children state their desires, share their concerns, and open their hearts on matters large and small. Yet their letters also are distinctive in their simplicity, directness, and humor—the latter being sometimes unintentional.

Hundreds more children's letters reach the Office of the President each week—including, perhaps, one or two from youngsters who will one day be leaders themselves, possibly even Presidents. One day, these correspondents may find themselves on the receiving end of such letters.