The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

Spring 2004, Vol. 36, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Trevor K. Plante

Plante was AWOL again. He finally returned on July 2, 1907, having been gone since June 30. This wasn't the first time that Wilfred Plante was considered absent without leave and it wouldn't be the last. In fact, he was becoming a frequent offender. All told, Plante was AWOL at least eleven times. His punishments ranged from being excused to serving thirty days labor without pay. What makes Plante's tale, and charges of AWOL, so interesting is that he wasn't even in the army at the time. Wilfred Plante, a former Union soldier who had served in the Twenty-fifth Massachusetts Infantry, was one of thousands of Civil War veterans living in a soldiers' home run by the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

Admitted to the Eastern Branch of the soldiers' home in Togus, Maine, on August 3, 1898, and assigned to Company D, Plante (member #11293) lived out the remainder of his life at the home until his death on October 31, 1926. He was buried in the home cemetery, now a national cemetery maintained by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Most genealogists have never heard of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Many are familiar with the U.S. Soldiers Home in Washington, D.C., or maybe even the Naval Home that operated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. While these two homes served retired members of the Regular Army and Navy, the federal government did not operate volunteer soldiers' homes until after the Civil War.

During the Civil War, many groups assisted veterans in several large cities in the North such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Cleveland. The United States Sanitary Commission ran several temporary soldiers' homes. Other asylums, often managed by female benevolent societies, offered short-term relief for disabled soldiers and sailors. During the Civil War, female philanthropist Delphine Baker, through her Chicago publication, the National Banner, pushed for the creation and support of a federally run asylum for disabled Union veterans. Eventually Baker moved to New York City and established the National Literary Association, incorporated in May 1864. The association's goal was to establish a national home for disabled soldiers and sailors through the publication and sale of the National Banner, which also promoted literature, science and the arts.

Baker worked diligently to collect signatures of prominent people for a petition supporting her cause. On December 8, 1864, a petition asking for "the passage of a bill appropriating money for the founding and support of a national home totally disabled soldiers and sailors of the army and navy of the United States," was referred to the Senate's Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia. More than one hundred people signed the petition, including William C. Bryant, Henry Longfellow, Horace Greeley, Clara Barton, Ulysses S. Grant, and P. T. Barnum. Other signers included New York and Washington clergymen and journalists, as well as a few politicians and government officials.

On March 1, 1865, Senator Henry Wilson, chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and the Militia, introduced what he called "a little bill to which there can be no objection." Wilson's bill to "incorporate a National Military and Naval Asylum for the relief of the totally disabled officers and men of the volunteer forces of the United States," passed on March 3, 1865, with no debate. The legislation incorporated the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers and listed one hundred prominent citizens on the asylum's board of managers. The large number of managers proved unwieldy, and on March 21, 1866, Congress passed new legislation lowering the number of members to twelve.

With this change, the board of managers got right to work looking for suitable branch locations for the new soldiers' asylum. One site considered for the new veterans institution was Point Lookout, Maryland. After little debate the location was rejected. The managers felt that the site of the former Confederate prisoner-of-war camp was not a fitting place to honor their disabled Civil War veterans. Soon the board focused on a bankrupt resort located at Togus Springs, Maine, located five miles outside Augusta.

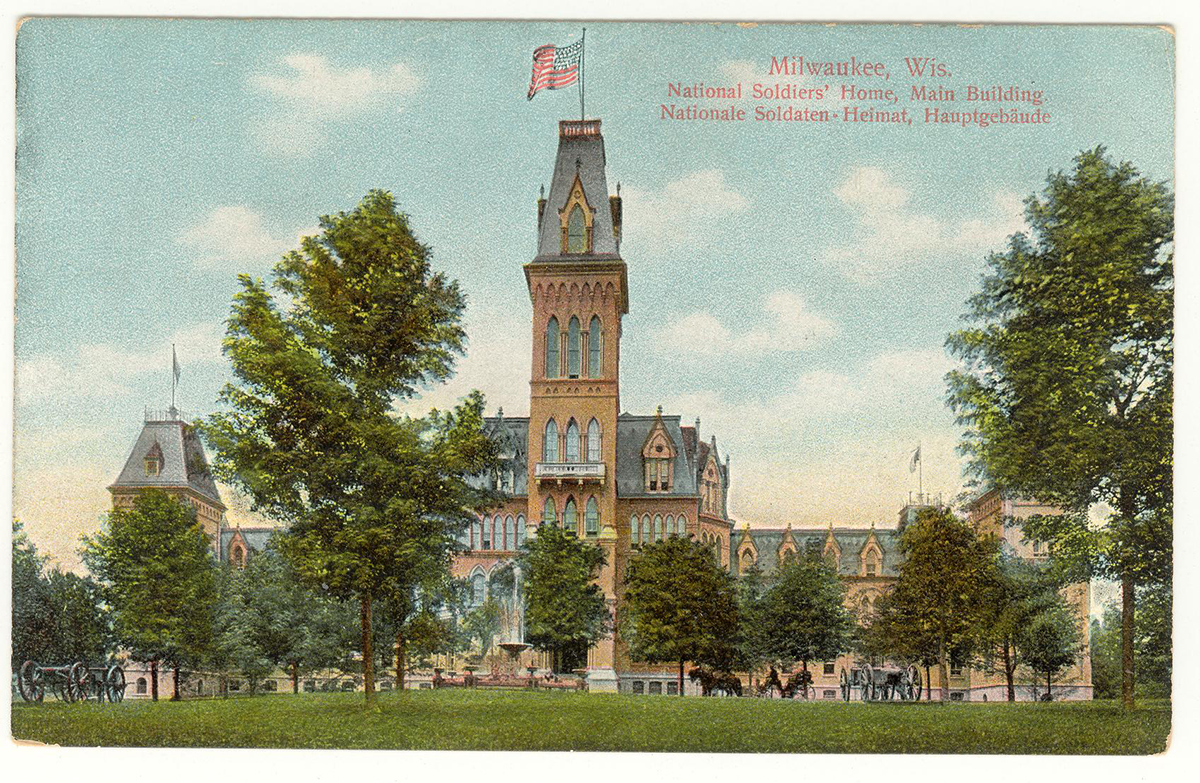

The first asylum opened in Togus Springs in 1866 as the Eastern Branch. The next year, two more asylums opened, the Central Branch in Dayton, Ohio, and the Northwestern Branch in Wood, Wisconsin, near Milwaukee. Eventually other branches followed: the Southern Branch in Hampton, Virginia; the Western Branch at Leavenworth, Kansas; the Pacific Branch at Sawtelle, California, near Los Angeles; the Marion Branch in Indiana; the Danville Branch in Illinois; the Mountain Branch at Johnson City, Tennessee; the Battle Mountain Sanitarium at Hot Springs, South Dakota; the Bath Branch in New York; the Roseburg Branch in Oregon; the St. Petersburg Home in Florida; the Biloxi Home in Mississippi; and the Tuskegee Home in Alabama.

Men were issued blue uniforms and loosely followed army regulations. Upon admission, each veteran was given a member number and assigned to a company. A company sergeant oversaw each company. The days were regulated with bugle calls waking the men in the morning, calling them to the dining hall, and putting them to sleep at night.

The role and operation of the asylum changed over time. In an effort to present their establishment as more of a home and less of a large bureaucratic institution, Congress changed the name of the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1873. Initially the asylum was merely a shelter for disabled Civil War veterans. The branch asylums lacked any organized form of recreation and leisure activities. Over time, the homes came to offer recreational activities and libraries, and churches were built. According to the 1900 board of manager's annual report, several homes maintained theaters, libraries, and billiard halls. At some of the homes, members engaged in activities such as dominoes, checkers, chess, backgammon, cards, boating, skating, pool, and croquet. At the homes' theaters, veterans were entertained with concerts, comedies, melodramas, musicals, vaudeville, and lectures. Of the eight homes run in 1900, six had suitable chapels, and all eight held Protestant and Catholic services.

Admission to the soldiers' homes was voluntary. Members could request admission to any home they chose and could request to be discharged as well. Sometimes veterans took advantage of this provision and entered and exited the home several times upon their own request. If a member was leaving for the weekend or a short period of time, the home issued a pass. Anyone who was late coming back from leave or gone without permission was considered absent without leave, a punishable offense. Members referred to their extra work duty punishments as "working on the dump." Each home maintained a guardhouse where guards stopped and checked visitors and confirmed that members had authorized passes.

Other war veterans were eventually included in the membership as well. It wasn't long before the branches became tourist attractions. Several of the homes had grand gardens where visitors came for weekend picnics. Others came to see many of the one-armed and one-legged veterans parading around in their blue uniforms. The Northwestern Branch boasted that it attracted 40,000 visitors in 1877. The Central Branch became so popular to tourists that the home ran a hotel for guests. By 1875, more than 100,000 people visited the home. During the next decade, that branch was attracting more than 150,000 visitors annually.

From 1866 to November 1874, the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was supported entirely by funds provided by fines and forfeitures imposed by court-martial and forfeitures on account of desertions from the army as provided for in the act of March 21, 1866. From 1875 to 1931, Congress made annual appropriations for the National Home as it did for other government institutions.

From 1866 to 1890, when pension laws were eased so that nearly every Union soldier was eligible for a pension, approximately one-third of the residents of the National Home received federal pensions. Historian Patrick J. Kelly concluded in Creating a National Home that the reason for this figure is because home managers routinely admitted indigent veterans, especially older men, who were unable to prove their disabilities were service related. After 1890, veterans were eligible for service pensions as opposed to pensions keyed to service-related disabilities. Although legislation initially incorporating the National Asylum gave the board of managers the authority to confiscate pensions of residents without dependants, the board did not exercise this option. In the early 1880s, Congress amended the act and eliminated the provision concerning the confiscation of pensions. It was up to individual home members to send any of their pension money to their wives or children. In 1899 Congress required home residents receiving pensions to apportion one-half of their payments to surviving wives or dependant children.

According to the annual report for 1900, the National Home cared for 102,722 veterans between 1866 and June 30, 1900, at a cost of just over fifty million dollars. Of the 29,578 veterans cared for in 1900, 29,051 were Civil War veterans, and 527 others served during the Mexican War and other conflicts. African Americans were welcomed at the National Home. Veterans who served in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War were afforded the same privileges of admission as white veterans. By 1899 only 2.5 percent (669) of the veterans assisted in the National Home were African Americans. This number is low considering that nearly 10 percent of soldiers who served in the Union Army during the Civil War were black. Black members lived in segregated quarters and ate their meals at separate tables.

After 1928, home benefits were extended to women. The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was taken over by the Veterans Administration in 1930 as part of the establishment of the VA. The branch cemeteries were also taken over by the VA and eventually became national cemeteries. By June 30, 1932, the population at the National Home was 22,503, comprising 708 Civil War veterans, 5,572 Spanish-American War veterans, and 16,223 World War I veterans.

Genealogical Research

The place to begin researching any Civil War Union veteran is the compiled military service record. The pension file—if the veteran, widow, or any dependents either applied for or received a pension—is another good source of information on the veteran. If you are lucky, you will find additional records that relate to the veteran's time at a soldiers' home in his pension file. Most of the information on Wilfred Plante, for example, was gleaned from his pension file. If the veteran lived in a soldier's home run by the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the Historical Registers described below are a must for research. In addition, there is limited information in Record Group 92, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, entry 591, Applications for Headstones for Soldiers Buried at Soldiers' Home, 1909 - 1923. This small series is arranged by state and home. Most likely this series will duplicate information already found in the Historical Register.

A record of veterans admitted to the homes is contained in "Historical Registers" that were maintained at the various branches. These registers are now at the National Archives in Record Group 15, Records of the Veterans Administration. A home number was assigned to each individual upon admission. The member retained his original number even if he was discharged and was later readmitted to the branch.

Each page of the register is divided into four sections: military history, domestic history, home history, and general remarks. The veteran's military history gives the time and place of each enlistment, rank, company, regiment, time and place of discharge, reason for discharge, and nature of disabilities when admitted to the home. The domestic history provides information about the veteran such as birthplace, age, height, various physical features, religion, occupation, residence, marital status, and name and address of nearest relative. The home history provides the rate of pension, date or dates of admission, conditions of readmission, date of discharge, cause of discharge, date and cause of death, and place of burial. General remarks contain information about papers relating to the veteran, such as admission papers, army discharge certificate, and pension certificate. Information was also entered concerning money and personal effects if the member died while in residence at the branch.

The home registers have been reproduced as National Archives Microfilm Publication M1749, Historical Registers of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866 - 1938. The microfilm is available at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and many of the National Archives regional facilities. Some of the regional sites have all of the microfilm rolls covered under M1749, while others maintain only the rolls for the soldiers' home that operated in their geographic region. For example, the Waltham, Massachusetts, facility holds only the rolls relating to the Eastern Branch of the National Soldiers Home in Togus, Maine. In addition to the Historical Registers, some other records relating to the soldiers' homes have also been reproduced as part of M1749. The microfilm publication also contains registers of death for Bath and Roseburg; funeral records for Bath and Danville; and burial registers and hospital registers for Togus. Please note that the National Archives does not have Historical Registers for the St. Petersburg, Biloxi, or Tuskegee homes.

The regional archives maintain only a select number of member case files for the homes that operated in their regions. The majority of the original case files for individual members were disposed of decades ago. Addresses and telephone numbers for National Archives regional facilities are printed at the end of this issue of Prologue. If you are interested in learning more about what life was like at the homes, consult the annual reports of the board of managers. These published sources can be found in the United States Congressional Serial Set available at the National Archives library in Washington, D.C. The serial set should also be available at a Government Depository Library in your area.

If you are interested in researching veterans at the U.S. Soldiers Home in Washington, D.C., or the Naval Home in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, you can consult Record Group 231, Records of the U.S. Soldiers' and Airmen's Home, and Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments. For more information on RG 231, contact the Old Military and Civil Records unit of the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Records in RG 181 relating to the Naval Home are located at the National Archives Mid Atlantic Region in Philadelphia. If you are interested in state-run homes (including Confederate soldiers homes and a variety of widows' and orphans' homes), contact the state archives for the state in which the home operated.

For more information on individual veterans who were residents in the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, write to Old Military and Civil Records, National Archives and Records Administration, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408, or contact us online

Branches of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

Typical Menu at the Branch Homes in 1875 and 1900

Trevor K. Plante is a reference archivist in the Old Military and Civil Records unit at the National Archives and Records Administration who specializes in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century military records. He is an active lecturer at the National Archives and frequent contributor to Prologue's Genealogy Notes.