From Pearl Harbor to Elvis: Images That Endure

Winter 2004, Vol. 36, No. 4

By Ellen Fried

One of the most popular photographs at the National Archives is an image of two famous men. They're not doing much, really—just standing there, clasping hands, smiling for the camera.

One day in 1970, Elvis Presley showed up at the northwest gate of the White House, bearing a five-page letter that he'd written on American Airlines stationery. "Dear Mr. President," it began. "First, I would like to introduce myself. I am Elvis Presley and admire you and have great respect for your office."

The letter went on to describe Presley's concern about the problems facing the country ("the drug culture, the hippie elements . . . ") and his interest in helping out—which he felt would require credentials as a "Federal Agent at Large." He concluded, "I would love to meet you just to say hello if you're not too busy."

President Richard M. Nixon's appointments secretary drew up a memo recommending the meeting. "You must be kidding," wrote Nixon's chief of staff in the margin of the memo. Nonetheless, a meeting was arranged, and it was photographed by White House photographer Ollie Atkins.

In 1975, the photographs—along with other official records of the Nixon presidency—were transferred to NARA, where they came under the jurisdiction of the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff. In the early 1980s, the photographs were part of a set of materials that were opened for public research.

One of the photographs came to the attention of a Chicago Tribune journalist, who wrote a column about it. The column was widely syndicated. One thing led to another; a comedian showed up on David Letterman's television show, wielding a copy of the picture.

Soon the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff was inundated with requests for reproductions. "For a while there," recalls staff member Steve Greene, "we had a boiler-room operation for handling these requests. We were getting hundreds of them a month."

The hoopla has died down since then, but the image continues to be popular. It's sometimes identified as the most requested photograph at the National Archives, which raises the question—what are some of the other most popular photographs?

As it turns out, identifying a single most popular photograph—or coming up with a "top ten" list—is virtually impossible. For one thing, photographs are found in NARA facilities all across the country. Each of NARA's presidential libraries has its own collection of images. Regional archives from Alaska to Georgia have photographs that document federal activities in their regions. Even in the Washington, D.C., area, photographs are held in various branches. For example, high-altitude aerial images are found in the Cartographic section of the Special Media Archives Services Division. Photographs that are closely tied to reports stay with those reports and are preserved in the branches that handle textual records. Each facility or branch handles image requests separately.

Another complication is that patrons have many ways of obtaining photographs. They can submit official requests by letter, fax, or e-mail, but they can also download many images directly from the Internet or visit a research room to make their own copies or scans. There is no practical way to track exactly how frequently any photograph is obtained, let alone to compare data from facilities or branches across the agency.

One thing is certain—the National Archives has an enormous number of photographs. Millions of them. And the vast majority of them—more than nine million—is held by the Still Pictures section of the Special Media Archives Services Division, at the National Archives facility in College Park, Maryland.

Every day, the branch's reference team handles requests and inquiries from patrons, and while the team may not have precise statistics, they have an awfully good sense of which images are most in demand. At Prologue's request, they put their heads together and came up with a list of ten photographs that they feel are currently most popular. Those images—along with the photograph of Nixon and Elvis—are reproduced here.

One thing that immediately leaps out at the viewer is that seven of the ten photographs are from World War II. But that's not so surprising when you consider that about two-thirds of the photographs in the Still Pictures collection are military images. The images held by NARA document the activities of the federal government, and defending the country is one of the government's major endeavors. And World War II was the central conflict of the twentieth century.

There are thousands of World War II images in the collection. What turns some of them into superstars? It seems to be a combination of factors. A photograph has to have aesthetic appeal. After all, photography is an art, and every photographer makes decisions about how to compose and frame each image. A photograph also needs to convey something crucial and essential; it needs to encapsulate a pivotal event, capture a defining mood, or both. And sometimes, there's yet more—an element of surprise, an unexpected juxtaposition, an ironic contrast.

For the United States, the first pivotal event of World War II was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Among all the photographs of that attack, the one that has proved most enduring is the navy photograph reproduced above. The photograph is striking in capturing the exact moment when the USS Shaw exploded. The billowing black clouds slice diagonally through the scene, echoing the angle of the palm frond that frames the image. And in that frame lies the irony: a symbol of tropical paradise embraces a picture of horror and destruction. Perhaps it's a similar, if much less tragic, irony that makes the Nixon-Elvis photograph so popular. There's a surprising juxtaposition of the straightlaced President of the United States in his business suit and the flamboyant King of Rock 'n Roll in his velvet cape and huge belt.

Other crucial moments of World War II are represented here, and each of the photographs captures a defining mood. The image of the D-day landing is shot from the perspective of a passenger on a Coast Guard craft. The viewer looks out across the ramp and into a vast abyss of uncertainty, just as the Allied soldiers did on that fateful morning in 1944. By early 1945, victory in Europe was in sight, and a sense of confidence and satisfaction seems to radiate from faces of the "Big Three" leaders who met in Yalta to plan the defeat and occupation of Nazi Germany and determine the shape of the postwar world.

Meanwhile, the war raged on in the Pacific, and nowhere was it more grueling than on the island of Iwo Jima. The American victory on that island was hard won, and the marines struggled to get to the top of Mount Suribachi. As seen in the photograph above, they continued to struggle to raise the flag—but raise it they did. The photograph conveys both the difficulty and their determination. From the moment it was first published, this photograph stirred something in the American psyche. It was a poignant image for a nation at war.

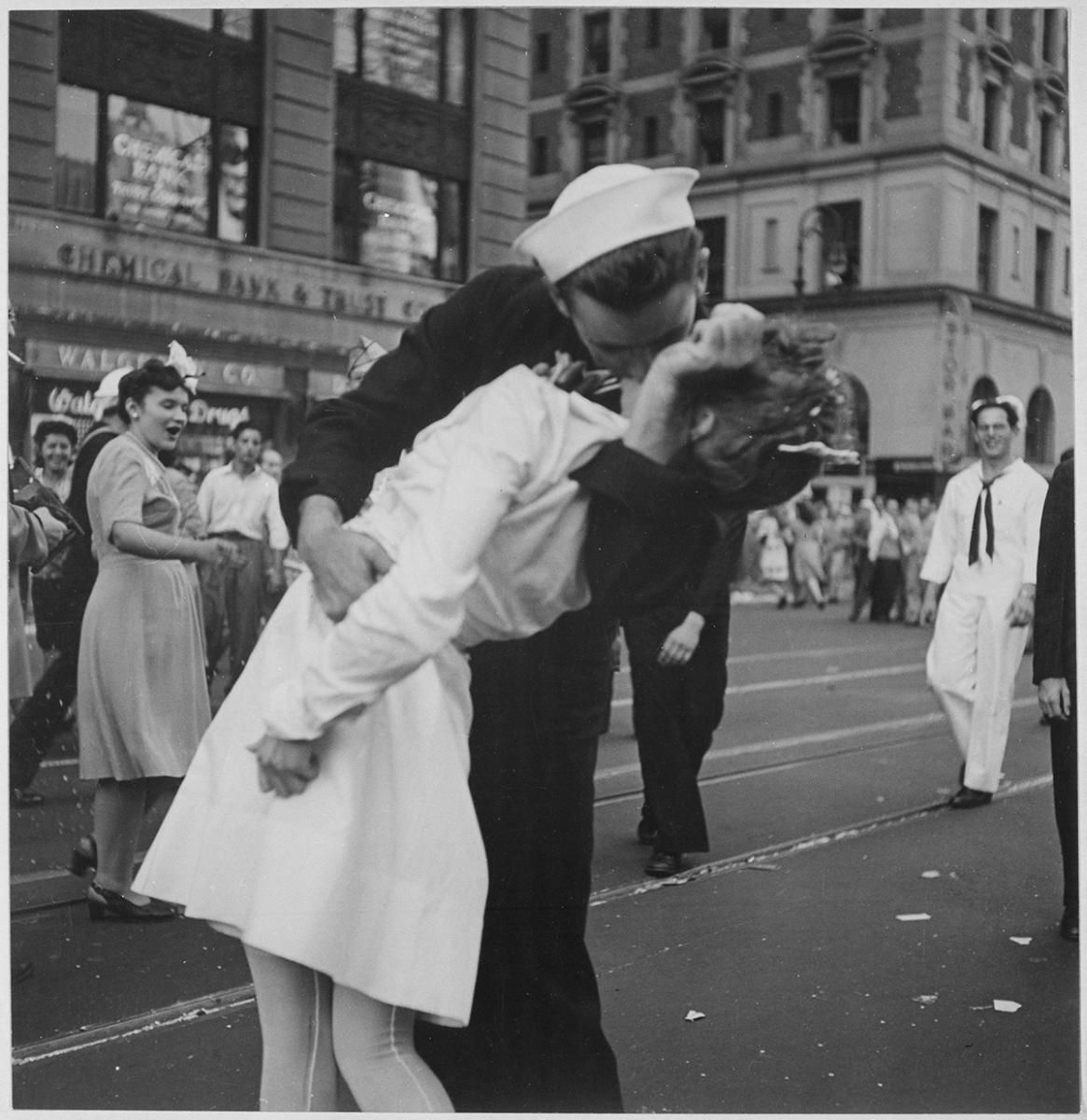

The photograph of the explosion of the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, composed vertically to encompass the full drama of the sixty-thousand-foot column of smoke, emphasizes the incredible power of the event that ultimately ended the war. And the photograph of the kiss on Times Square captures the sheer unbridled exuberance felt by Americans as the war came to an end.

Posters, too, are represented among the holdings of the Still Pictures collection, and a World War II–era poster is included here. What makes the "We Can Do It" poster so popular? It seems to have meaning on many levels. It captures a positive, "can-do" attitude that is very American; the image and phrase have been borrowed for many purposes since then. It also encapsulates a turning point in the evolution of women's roles and rights in American culture. World War II was the first time that women took over men's jobs on a large scale. They kept the factories running; they made the planes that the men flew; they brought home salaries. And, as the poster reflects, they felt pride in all that. Their experience during World War II helped lay the groundwork for the women's movement in the 1960s.

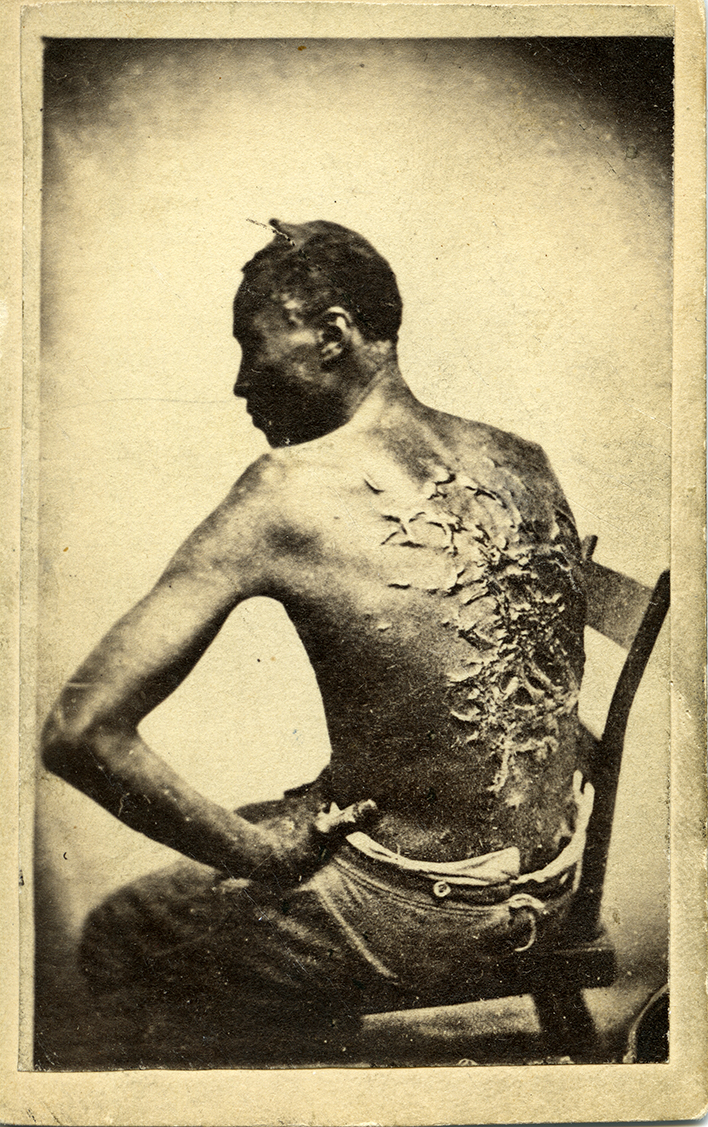

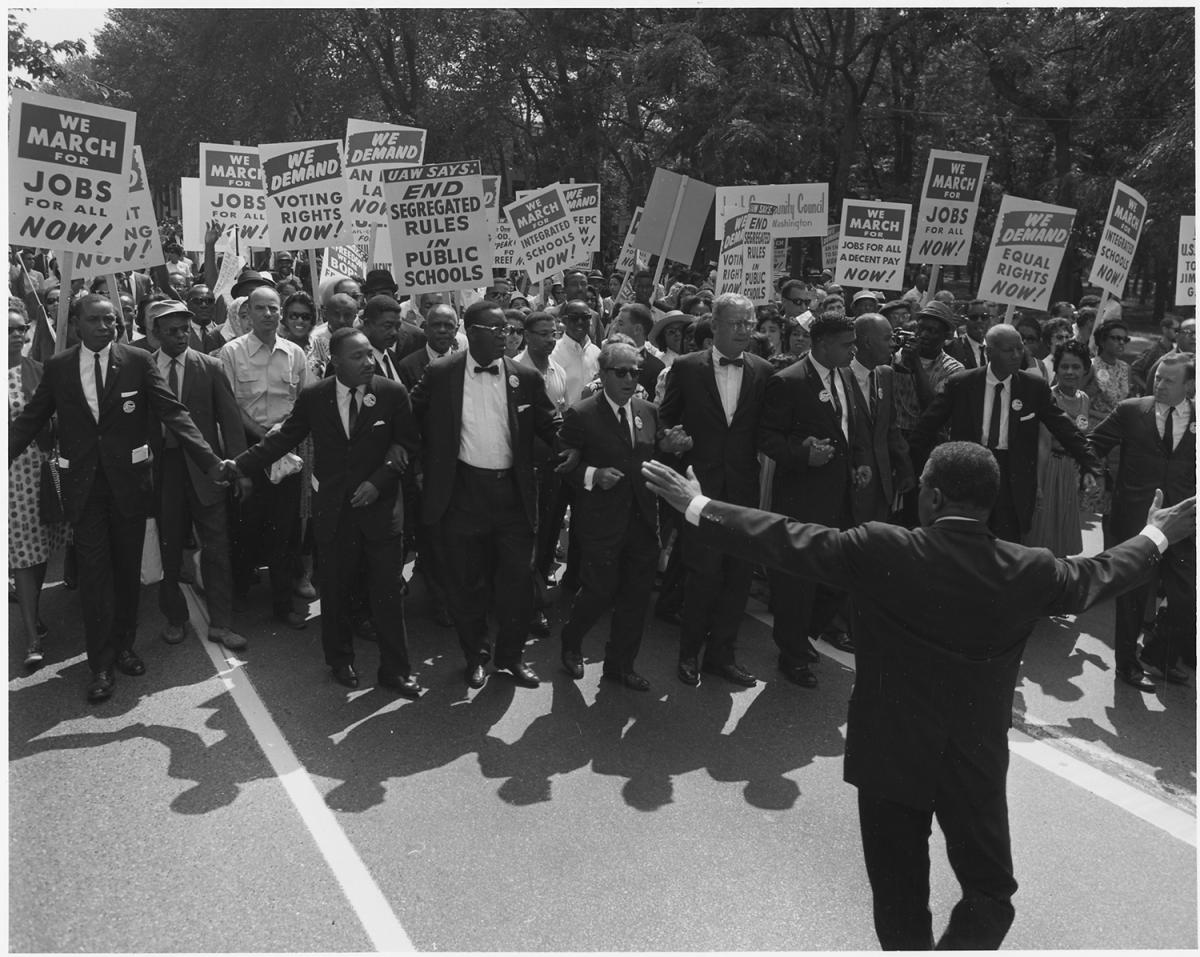

Two other images in this set chronicle a struggle for rights. One is the 1863 photograph of a slave who had been savagely beaten by his overseer. The gracefulness of man's pose contrasts sharply with the stunning gruesomeness of his wounds, capturing the horror of slavery. A century later, a photograph of the March on Washington revealed what was central about the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. The movement was nonviolent, but it was forceful; the photograph captures that combination of peacefulness and power. It also captures the breadth of the movement. The March on Washington showed the nation that this struggle wasn't a matter of one group fighting another; it was blacks and whites and men and women marching together for fundamental changes in American society.

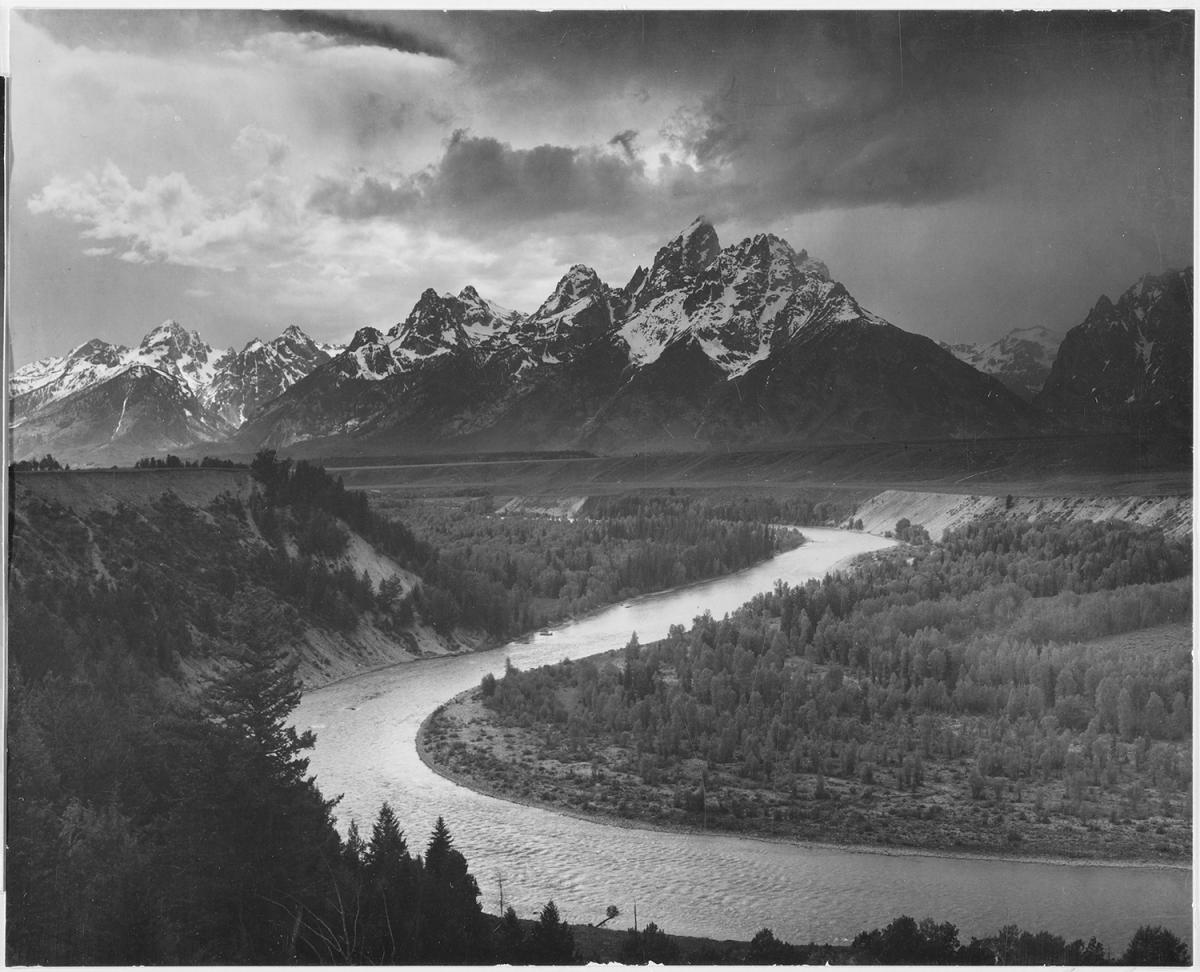

One image on these pages documents neither conflict nor struggle nor triumph; it is an image of pure beauty, capturing a slice of the American landscape. Some of the nation's most famous photographers—including Ansel Adams—have taken photographs for the federal government, as Adams did for the National Park Service. The Ansel Adams photographs in the National Archives are the only images of his that are in the public domain. What makes the one of the Snake River so popular? Perhaps it's the fact that this image, like others on these pages, captures a surprising juxtaposition. In this case, the serenity of the river contrasts sharply with the looming stormclouds.

As events unfold in a new century, what moments, scenes, and images will stand out? In a few decades, an article such as this might feature a different set of photographs, documenting a different set of struggles and achievements and perhaps new ways of looking at the land. Chances are, though, that the images will share much in common with this set, including an aesthetic appeal, a way of capturing essential moments and moods, and an ability to highlight surprising contrasts or to make unexpected connections.