Finding Ordinary Americans with Extraordinary Stories

Fall 2005, Vol. 37, No. 3

By Miriam Kleiman

In preparation for the opening of the Public Vaults exhibition at the National Archives Building in November 2004, public affairs specialist Miriam Kleiman was assigned to track down and bring to Washington some of the people mentioned in the exhibition. This is her account of her search for the ordinary Americans whose stories are preserved in the National Archives.

Gina Sims was just three years old when her father, Clifford Sims, was killed in Vietnam in 1968. Staff Sergeant Sims was leading a squad through dense woods in Hue when he heard the sound of a booby trap being triggered in front of his men. He yelled to others to get out and then threw his body on the exploding device. He died the next day. The Army awarded him the Medal of Honor posthumously.

This story of valor is included in the National Archives and Records Administration's Public Vaults permanent exhibition, in the "Prepare for the Common Defense" vault. Also included is a picture of Gina and her mother, Mary, receiving the Medal of Honor from Vice President Spiro Agnew on December 2, 1969. Young Gina appears in a blue dress with a matching hair bow, a strand of pearls, and little white gloves.

I saw this striking picture and wondered, "What happened to that little girl?"

As part of an effort to promote the Public Vaults, which opened in November 2004, I had begun to search for some of the people who appear in the exhibition—in stories, letters, photographs, and documents. For this ground-breaking exhibition, we wanted to find ordinary people, not just the famous among us, behind some of the 1,100 original records or facsimiles that are used in the various individual exhibits.

At the outset, I had many questions.

Since the exhibition spans the length of American history, how far back should I go—30 years? 40? 50? 60? How far back is a "reasonable" amount of time? Were these people still alive? Had their names changed? Did they still live in the United States? If I did locate them, how would they respond? Would they remember the letters they wrote or the pictures they posed for? Would they object to being included in a permanent exhibition?

Armed with copies of the documents, photographs, and letters—and using Internet search engines as tools—I began my search.

I started with the little girl in the 1968 photograph. The Internet turned up a 2002 e-mail Gina had written to the men of her father's airborne division battalion requesting photographs or information about her father. I contacted Gina in Colorado Springs, where she now lives with her husband and three daughters.

Gina seemed touched by the call and accepted our invitation to the opening of the Public Vaults in November—36 years after she was first here. She brought her youngest daughter, Kristin, who is now three—the age Gina was when her father was killed. After the event, Gina wrote that "words cannot express the joy and love I feel in my heart" at being included and seeing her father remembered.

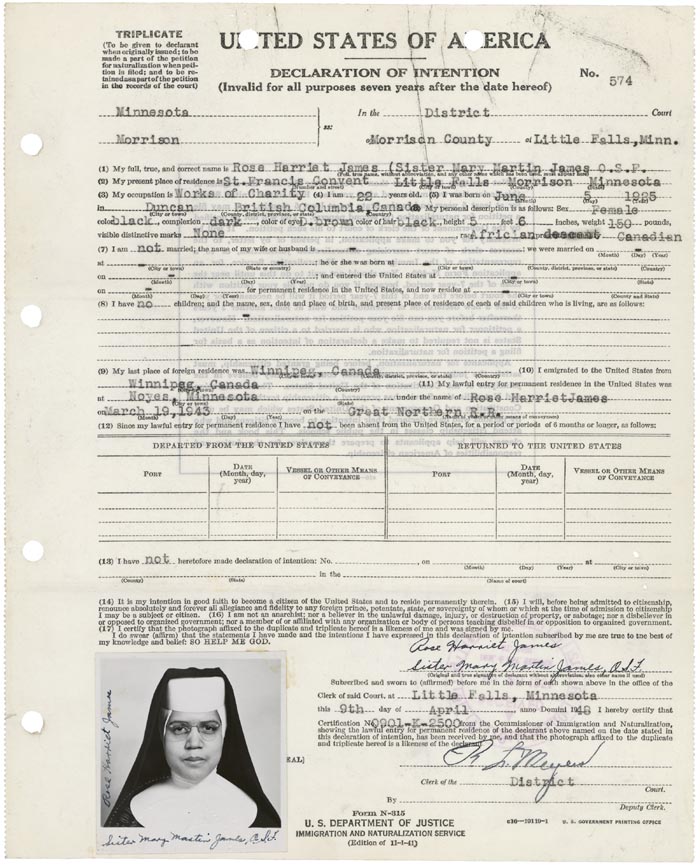

Another picture in the exhibit caught my eye—a black-and-white naturalization photograph of a young African American woman in a full nun's habit. Her photograph appears on her Declaration of Intention for U.S. citizenship that was filed in Little Falls, Minnesota, in 1943 and appears in the American citizenship section of the "We the People" vault.

Eighteen-year-old Rose Harriet James listed the St. Francis Convent as her residence and "works of charity" as her profession. My first call was to the convent. After sending a copy of the naturalization form, I received an e-mail with a telephone number, then spoke with the woman in the 1943 picture.

I learned about her difficult childhood in Canada and the positive experience at a Catholic boarding school that led her to choose to become a nun. Being of mixed racial heritage, she sought an inclusive convent and found the St. Francis convent in Little Falls.

I also learned that she had annulled her vows and left the church in 1967. While no longer a nun, she continued to do "works of charity" by working with juvenile delinquents and addicts. She also leased, owned, and operated buildings for the poor and indigent. Told of her role in the Public Vaults, she wrote that while she was honored, "[it] surprises me to be chosen for the exhibit and is indeed humbling." She was unable to attend the opening, and we learned, sadly, that she was murdered later that month.

I was intrigued by the letters from children in the "Dear Uncle Sam" section of the "Form a More Perfect Union" vault. One unusual letter in the stack interested me a great deal—a letter written in Braille to President Dwight D. Eisenhower by a young boy in the fall of 1956. Thirteen-year-old John Beaulieu offered the President the following campaign stump speech: "Vote for me. I will help you out. I will lower the prices and also your tax bill. I also will help the negroes, so that they may go to school."

The return address listed Perkins School for the Blind (Helen Keller's alma mater) in Watertown, Massachusetts. After my Internet searches led nowhere, I called the Perkins School but was not optimistic. After all, John had not been a student there for nearly 50 years. Much to my surprise, a helpful staffer at Perkins turned up a current address and telephone listing for John! One day later, I spoke with John for the first time. He clearly remembered the letter and explained how it evolved from a sixth-grade government class project in which students presented mock stump speeches and voted.

John's mock Eisenhower stump speech was a hit with the class, and his teacher suggested he share his speech with the President. John wrote a careful letter in Braille, and his teacher wrote out the words over the Braille.

A few weeks later, John received a response from the President himself, who wrote: "It was nice of you to send me a little speech to help win the election. Your good luck wishes for November mean a lot to me too, and I am very grateful to you for them."

For John, the call from the National Archives was another wonderful surprise, albeit nearly 50 years later. John is now a father and a grandfather of five. The boy who once suggested that the President pledge to lower taxes now works for the Internal Revenue Service! He and his family spent a week in Washington at the Public Vaults opening events, during which he proudly shared his story with archival staffers, invited guests, and the media.

"It is absolutely amazing to think that something I did as a child would get this kind of recognition. I still find it hard to believe, but I know that it's real because I was there," he later said.

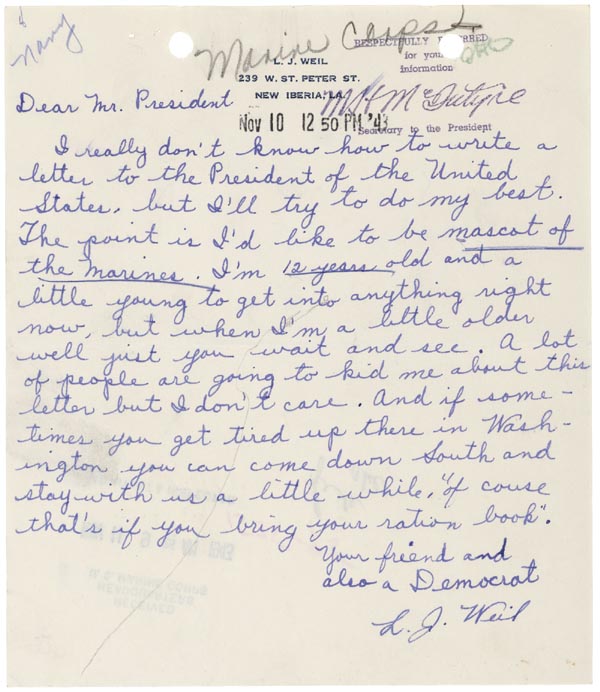

"Dear Uncle Sam" includes a delightful letter from another boy, a 12-year-old in Louisiana named "L. J.," who wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1943 and offered to serve as a "mascot of the Marines." He even invited Roosevelt to visit his home "if you get tired up there in Washington," but insisted that the President bring his own ration book.

"A lot of people are going to kid me about this letter," he wrote, "but I don't care." He signed the letter: "Your friend and also a Democrat L. J. Weil."

Records show that L. J. received a polite "brush off" from the U.S. Marine Corps headquarters a week later, applauding his patriotism but asking him to wait until the "required age for enlistment" in order to become "a real Marine."

I viewed this letter with little hope—What did "L. J." stand for? Even if I did find L. J., given that the letter was more than 60 years old, would he even remember writing it?

After many failed phone attempts, in late August of 2004 I tried yet another listing under L. Weil. A man answered "This is L. J." I identified myself and asked if by chance he was from New Iberia, Louisiana. He said yes. I asked if he remembered writing to President Roosevelt in 1943. I started reading the letter, but the man was impatient so I jumped to his closing: "Your friend and loyal Democrat L. J. Weil."

He paused and gruffly responded:

"I'm a lifelong Army man and I'm not a Democrat—do you still want to talk to me?"

I eagerly responded yes, at which point he said I had interrupted his golf game (he had transferred calls from his home to his cell telephone) and ruined his concentration. I called again the next morning. L. J. told me he had lost the golf game—thanks to my interruption. However, he did listen to me describe the exhibit and explain my interest in his correspondence. After the call, I mailed him information about the Public Vaults and copies of his letter and the Marines' response.

When I next heard from L. J., his tone had warmed considerably. He updated me on the 60 years that had passed since his "Marine mascot" offer was turned down. L. J. attended a military academy for high school and joined ROTC and then the Army in 1951. He served as a Special Forces Green Beret in both Korea and Vietnam and retired from the Army in 1971. He has three children and four granddaughters.

L. J. Weil, along with his son, Bob, participated in the public opening of the Public Vaults exhibition on November 15, 2004. They were delighted to see the display facsimile of L. J.'s 1943 letter. He wrote that he had been given "a great honor by having my letter displayed in the National Archives."

"Provide for the Common Defense," the military section of the exhibition, offers many stories of heroism and valor. Although another part of the exhibit covers women who entered the workforce during World War II, given restrictions on women in the military, the defense section is almost entirely male—with the exception of Virginia Hall.

Hall's life is a spectacular cloak-and-dagger spy story of a woman who refused to accept "no" as an answer. She dreamed of working for the U.S. Foreign Service but was rejected because she had lost a leg in an accident, and the State Department had a ban on hiring any amputee. When a family friend "pulled strings" and wrote on her behalf to President Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull informed her that she had many options in the clerical ranks and could "become a fine career girl in the Consular Service."

Rather than become a secretary, in 1941 Hall became a British agent and went to France and to help organize French Resistance in Vichy. In 1943, Gen. William Donovan's Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), recognized her nonclerical skills and hired her as an agent. When World War II ended in 1945, Hall received the U.S. Army's Distinguished Service Cross, the only female civilian in the war to receive the army's highest military honor after the Medal of Honor. After the war she became one of the new CIA's first female officers.

Virginia Hall was born and raised in Baltimore, just under 60 miles from where her OSS records are stored in the National Archives facility at College Park, Maryland. Hall had no children, but her niece Lorna Catling lives in Baltimore now. I found Lorna and asked her about her brilliant and daring aunt. Hall followed the CIA ban on discussing covert action and rarely spoke of her war experiences. However, her niece shared that Hall—whom the family remembers fondly as "Aunt Dindy"—raised French poodles, gardened, and devoured spy novels. Lorna Catling and her daughter Linda joined us for the Public Vaults opening.

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams have their places of importance in the National Archives, along with Gina Sims Townsend, Rose Harriet James, John Beaulieu, L. J. Weil, Virginia Hall, and many others.

For nearly 70 years, millions of Americans have visited the National Archives to see the old parchment documents that form the basis of our democracy. However, few knew that just beyond the Rotunda were stacks and stacks of boxes full of documents that might contain information about their own lives and families. Many people researching their family histories have been surprised to find the paper trail of immigration records, naturalization records, census schedules, draft cards, and homestead applications.

In a democracy, the records of the country not only belong to us, but they are also about us—they tell the story of our lives, our jobs, our families. And the Public Vaults exhibition clearly demonstrates that the National Archives holds records about not only our Presidents, inventors, generals, and other historical figures but also many others—teachers, educators, students, farmers—ordinary Americans.

When I walk through the Public Vaults, I do not see a static exhibit. I recognize the faces and hear the voices of the people who shared in the opening of the Public Vaults—who shared their lives and their stories about becoming and being an American.

Miriam Kleiman, a public affairs specialist with NARA, first came to the Archives as a researcher in 1996 to investigate lost Jewish assets in Swiss banks during World War II. The results of that research have appeared in major print and broadcast media. She joined the agency in 2000 as an archives specialist and is a graduate of the University of Michigan.