Winema and the Modoc War

One Woman's Struggle for Peace

Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1

By Rebecca Bales

© 2005 by Rebecca Bales

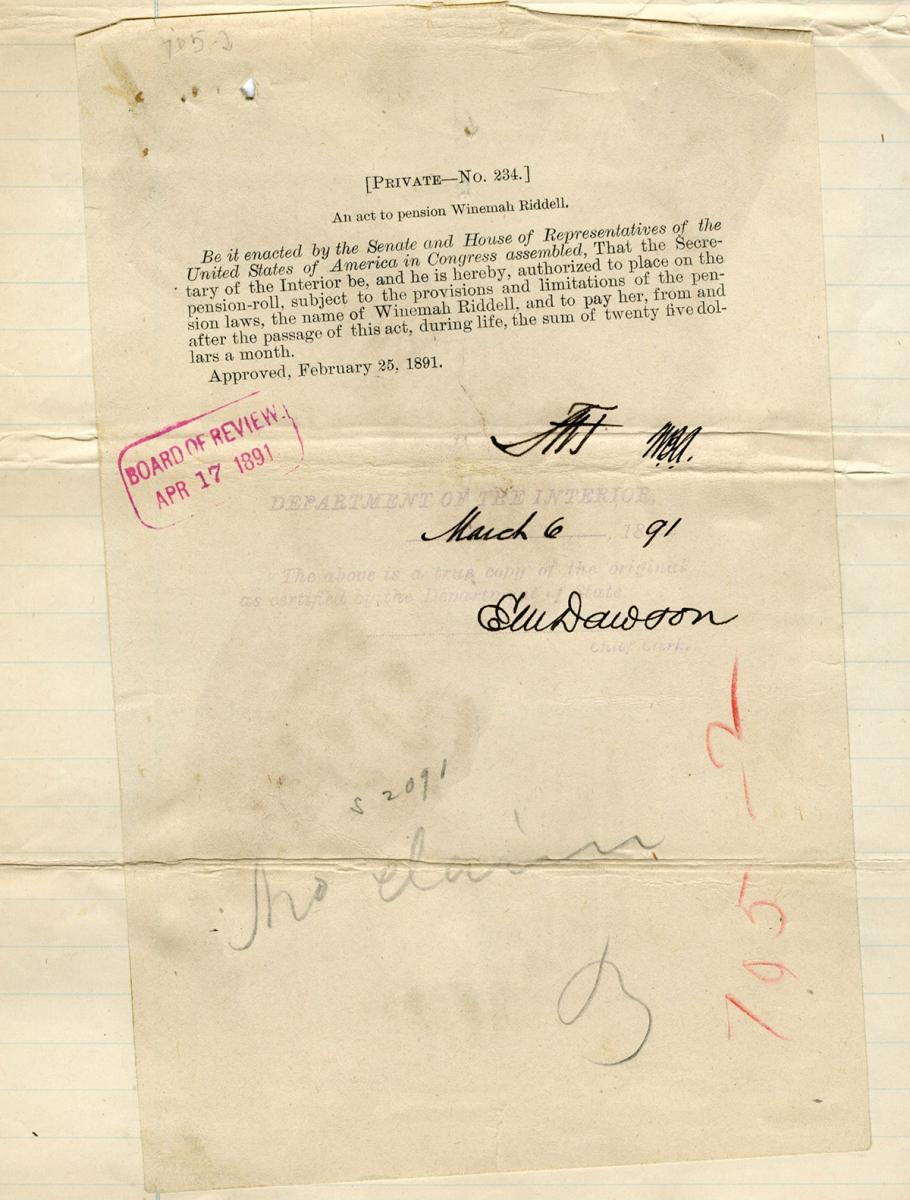

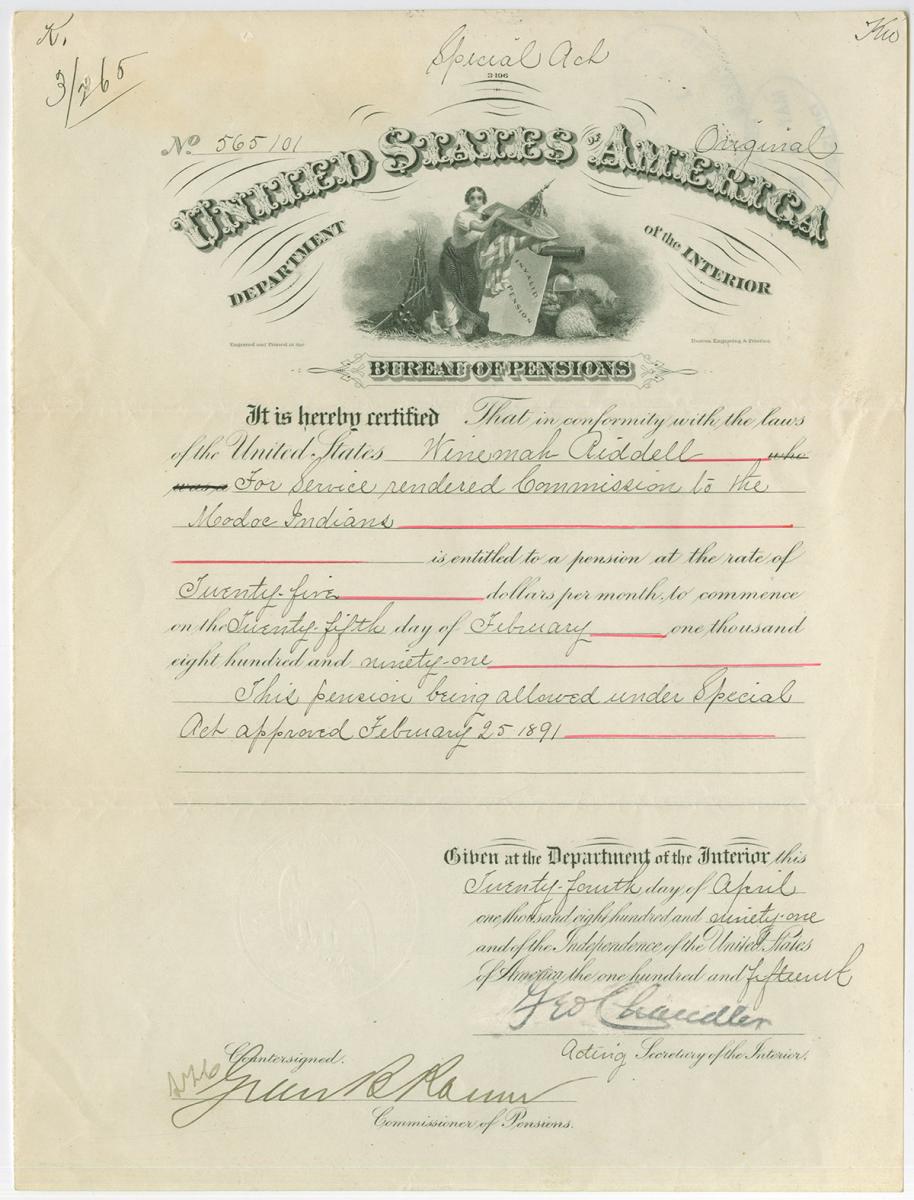

On February 25, 1891, Congress passed a very unusual piece of legislation. It awarded "Winemah Riddell [sic] . . . a pension at the rate of twenty-five dollars per month."

It is not unusual to find thousands of names in the pension files housed in the National Archives. What is unusual is that a woman received it for her courage in battle. And even more unusual is that Winema Riddle was a Native American woman of the Modoc Nation.

Historical sources often reflect roles of men who influenced history over time, but in them are sometimes found accounts of women's deeds. Through a multitude of sources, Winema's story unfolds, illuminating actions and people who, with her, shaped events in the latter half of the 19th century.

Winema Riddle was a Modoc woman whose life story illuminates Native American women's roles in history through her interactions with outsiders. She married outside her Nation, she became a mediator for her people, and she earned a military pension from Congress for her actions in time of war by saving a federal official's life.

Winema gained national attention because of her role in the Modoc War of 1872–1873, a war that lasted approximately eight months but that finds its roots in the Indian policy of the 19th century. In 1864, under pressure from settlers, the government decided to move the Modocs onto the Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon. The Klamaths, however, were historic enemies of the Modocs, and some Modoc people left the reservation for their old homes. The U.S. Government sent Federal troops to move the Modocs back to the reservation, and in 1872 the two sides clashed.

This is the story of how Winema Riddle worked for peace between her native Modocs and the U.S. Government.

To understand the importance of the pension Winema received, we must explore the events and personal history surrounding this woman who, for the most part, has been overlooked in the pages of history.

The Modocs' ancestral homeland spans the border of California and Oregon. For centuries the Modocs lived in this area, raising their families and establishing a society based on interdependence with each other and on extensive trade networks throughout California and the Pacific Northwest.

The arid environment is relatively inhospitable, but it did not impede the formation or growth of the Modocs as a viable and vibrant nation. Born and raised in the ancestral homeland of the Modocs, Winema's family nurtured her and imbued her with the values of her people, but she herself stretched the boundaries of gender and race.

Winema proved her courage in her early life during the 1850s. By all accounts, it is clear that one courageous deed set her apart from her peers early on. When she was a young teen, she saved a canoe full of children from being dashed in strong rapids by steering it to safety, earning her the name "Winema," which translates into "woman chief." Such deeds continued throughout her life.

Another example of her courageous character was her defiance of her father (and Modoc tradition) when she refused to marry the young man her family had chosen for her. Instead, she ran off and married Frank Riddle, a Kentuckian who had come to California in 1850 to seek his fortune in the gold fields.

Her marriage to Frank resulted in a short estrangement from her people and her family; however, Frank sought to gain her father's approval of their marriage and did so by meeting the obligations of a Modoc groom. He gave several horses to his new father-in-law, and in return, her family gave gifts to Frank to welcome him as Winema's husband. Frank and Winema settled close to her family in the Lost River area in California after their marriage.

The bonds between the Riddles and the Modocs established their role as critical players that would grow in the following decades. Winema's quick study of white ways helped her as both wife and mediator. Her fluency in the Modoc language (Lutuami) and her working knowledge of English gave her unique skills with which she could act for peace between her people and outsiders.

The 1840s, the decade in which Winema was born, was one of the most pivotal in California and Oregon Indian history. With the westward movement of white Americans, Native Americans throughout the American West experienced dramatic changes in their societies. The gold rush compounded these issues.

The Modocs felt the impact as non-Indians sought different routes to the burgeoning urban areas and the gold fields of California and Oregon. Indeed, as the westward movement gained momentum, so did the unease that enveloped Modoc country throughout the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. These events influenced Winema in several ways. First, her family and people had to adjust to new circumstances, many of which were out of their control. As they met new challenges and threats to their subsistence, they were drawn into similar problems their neighbors experienced, including the call to remove natives from the area as settlers set their sights on northern California and southern Oregon.

Complaints by settlers bombarded the Oregon Superintendency and the Indian Office in Washington as early as 1851. In July of that year, Oregon Superintendent Anson Dart reported difficulties in southern Oregon and recommended that the permanent boundary line between California and Oregon be set. This suggestion would have put the Modocs under the jurisdiction of Oregon even though most of them, including the Riddles, resided in California. The Modocs needed to find a way not only to maintain their land base but to protect their families and customs.

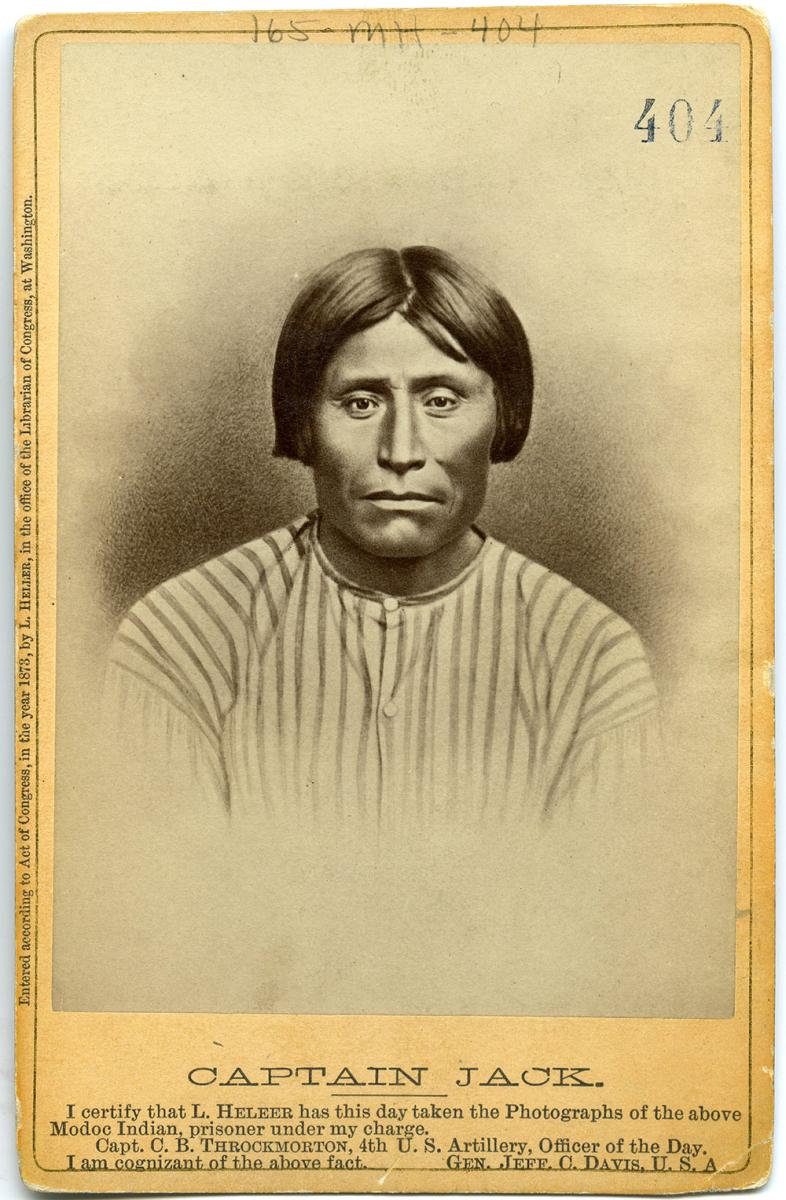

Unease became outright hostility in 1852, when a volunteer regiment from Yreka led by Ben Wright sought vengeance for an attack on an emigrant party headed for California. Evidence indicates that the Modocs were not responsible, but it was their neighbors to the south, the Pitt Rivers, who perpetrated the attack. Wright, however, made no distinction between the Pitt Rivers and Modocs, and he and his men slaughtered a village of about 40 Modocs. Some of Winema's family members lived in this village, including her cousin, Kintpuash, whom whites later called Captain Jack. He witnessed the murder of his father and other family members. This event would not only intertwine Winema and Kintpuash's lives on levels other than familial obligations but influence the future of their people.

In 1862 Commissioner of Indian Affairs William P. Dole reported:

All, or nearly so, of the fertile valleys were seized; the mountain gulches and ravines were filled with miners; and without the slightest recognition of the Indians' rights, they were dispossessed of their homes, their hunting grounds, their fisheries, and, to a great extent, of the production of the earth.

The Modocs' struggle to maintain their subsistence patterns became desperate as more non-Indians moved into their territory. They appealed to the California Superintendency to secure an area in their ancestral homeland for their own use. They asked for assistance from Judge Elisha Steele, who with the help of rancher John Fairchilds and Frank and Winema Riddle, negotiated a peace in 1863. This agreement would have established a reservation in northern California for those who assented to the treaty. In turn, the Lost River Modocs agreed to allow safe passage through their territory and to maintain peace with settlers and neighboring native nations.

The Modocs who agreed to this treaty felt secure in the knowledge that they would remain in their homeland under the protection of the California Superintendent. However, because Congress and the Indian Office had not authorized Steele to enter in such an arrangement, objections from Washington, D.C., and settlers soon arose. Unaware of the bureaucratic and communication problems between the California Superintendency and the Indian Office, the Modocs continued to live in their homeland, often visiting white towns to trade and to seek employment.

The following year, representatives from the Indian Office notified the Modocs of an upcoming treaty council through which the Modocs would be ensured suitable land on which to live. The treaty, signed in October 1864, provided land for all Modocs within the boundaries of the Klamath Reservation—not the Lost River area.

As tension grew throughout northern California, government officials were determined to find solutions. Between 1851 and 1890, the prevalent solution to the Indian problem was to place them on reservations where the United States could watch over them. However, there was an obstacle to overcome—how to get their compliance to move and remain on the reservations.

This government policy guided Modoc action and drew Winema into the national spotlight. The Modocs split between those who remained on the reservation under the leadership of Old Schonchin and those who later left and argued that officials were inconsistent and unjust in implementing the policy.

When Lindsay Applegate, one of the first white settlers in the southern Oregon area, became subagent for the Klamath Agency in 1865, one of his main tasks was to convince the Lost River Modocs to come to the reservation. He informed the commanding officer at Fort Klamath that he would represent the Modocs, who "have frequently called upon me and now for the last time to represent their grievances. . . . [They] say . . . it [the reservation] was not a safe place for them." The Modocs complied and moved to the reservation, but very little time passed before their concerns became firm reality. As they had feared, they were the target of Klamath harassment, and they did not receive the supplies promised them. Many Modocs moved several times between 1865 and 1870 to and from the reservation as conditions worsened and the government took no action.

In 1869, as the crisis on the Klamath Reservation continued, President Ulysses Grant and his new administration, struggling with the issues of Reconstruction and budgetary issues, refocused Indian Policy. Grant's administration sought to redirect military personnel and resources from reservation administration and implemented the "Peace Policy," shifting Indian agencies on reservations from military supervision to church management.

In compliance with the Peace Policy, Alfred Meacham, a Methodist minister, became Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon in 1869. Meacham worked closely with several officials and Winema in trying to bring peace to a troubled region. That same year President Grant ordered the army to force the Modocs back to the Klamath reservation; the Modocs complied, but little had changed. Upon their return, Meacham supplied them with blankets and goods, and O. C. Knapp, the commanding officer of Fort Klamath, supplied flour and beef. The Modocs, however, again experienced trouble with the Klamaths, who harassed them, often taking their supplies. Again they left the reservation for the Lost River area in California.

In March 1870 Knapp ordered the Modocs back to the reservation and sent a detail of soldiers to accomplish this goal. Approximately 45 Modocs had not returned to the reservation. Knapp reported, "on the 17th [the soldiers] started after these Indians, found them at Hot Creek Cal. on the 19th and returned to the Agency on the 23rd. Had no trouble in bringing them in." The Modocs tried to settle on the reservation peacefully, but their uneasy history with the Klamaths prevented their adjustment to reservation life. Many times Kintpuash and other Modocs brought their problems to Knapp's attention. The solution Knapp offered was to move the Modocs to a different part of the reservation. The Modocs did move, but the problems did not cease.

The Modocs grew tired of Knapp's moving them to different areas and the lack of a permanent solution to the conflicts. In the spring of 1870, many of them left the reservation for the last time.

When more than 100 Modocs left, settlers' apprehensions increased. Superintendent Meacham proposed a possible solution to the increasing tension: the creation of a subagency at Camp Yainax on the southern border of the Klamath reservation. In his annual report he "recommended the establishment of the band on a reservation to be set apart for them near their old home where they could be subjected to governmental control and receive their share of the benefits of the treaty." This proposal had the potential to solve the problems occurring in Oregon and California—the Modocs would be away from the Klamath; the Oregon Superintendency could supervise them with the help of the Californians; and the government would have direct supervision over them, thereby mollifying the settlers. However, as Secretary of the Interior J. D. Cox later reported, "No action on this recommendation was ever taken by this Department."

Between 1867 and 1871 it is clear that the Modocs tried to negotiate, sometimes with the assistance of Winema Riddle, but their pleas for a fair resolution fell on deaf ears. By 1872, when conditions became unbearable, the Modocs were determined to stay in the California-Oregon border area, having set up camp along Link River. But an effort in November 1872 to bring them back to the reservation forced them to split into separate parties, one led by Kintpuash, another by Hooker Jim. They decided to meet in the Lava Beds, a natural fortification in California. Kintpuash headed immediately for the Lava Beds, but Hooker Jim chose a different path. He attacked a number of settlers, killing men but sparing women and children.

When he reached the Lava Beds and announced these activities, Kintpuash realized that the United States would not let this incident go unpunished. Indeed, the Oregon governor and citizens demanded the extermination of the Modocs. The government had other ideas and wanted the killers turned over for trial and execution. Kintpuash was between a rock and a hard place. Ultimately, he refused to give any of his people over to a justice system he did not trust. As a result, war ensued, bringing the Modocs and Winema national attention.

After the war broke out in November 1872 and tension grew, the government realized that the solution to these problems was to either force the Modocs onto the reservation (which had failed miserably) or to negotiate their return in a peaceful manner. Although the war was inevitable, and it looked as if it would be a long affair, the Modocs were willing to negotiate and sent word that they would accept a reservation in the Lava Beds, but the answer was unequivocally negative.

Communication was very difficult for several reasons. Mistrust ran high, and because Kintpuash's band was entrenched in the Lava Beds, runners and messengers willing to carry important messages were hard to find. Winema was up to the task. Although Winema's activity during the reservation conflicts in the late 1860s had been limited (she and Frank remained in California while the other Modocs moved back and forth), the continuation of the war directly changed her services and illuminated her abilities once again as peacemaker. As a primary interpreter, Winema carried words between the Modocs and U.S. officials.

In February 1873 progress seemed to be made as the Modocs and the officials in both California and Oregon began communication through messengers. The Modocs were clearly unhappy with the way the United States carried out the treaty stipulations, but they were not averse to further negotiations. This position did not alleviate the anxiety of settlers, nor were the Modocs' concerns of primary importance until hostilities became imminent in California. Consequently, President Grant and his advisers decided to follow Meacham's earlier suggestion to settle the Modocs at a separate subagency at Klamath. But they had to find a way to bring the Modocs to the table for negotiations. Consequently, Grant ordered a peace commission established to bring the recalcitrant Modocs onto the reservation and those who had killed the settlers to justice.

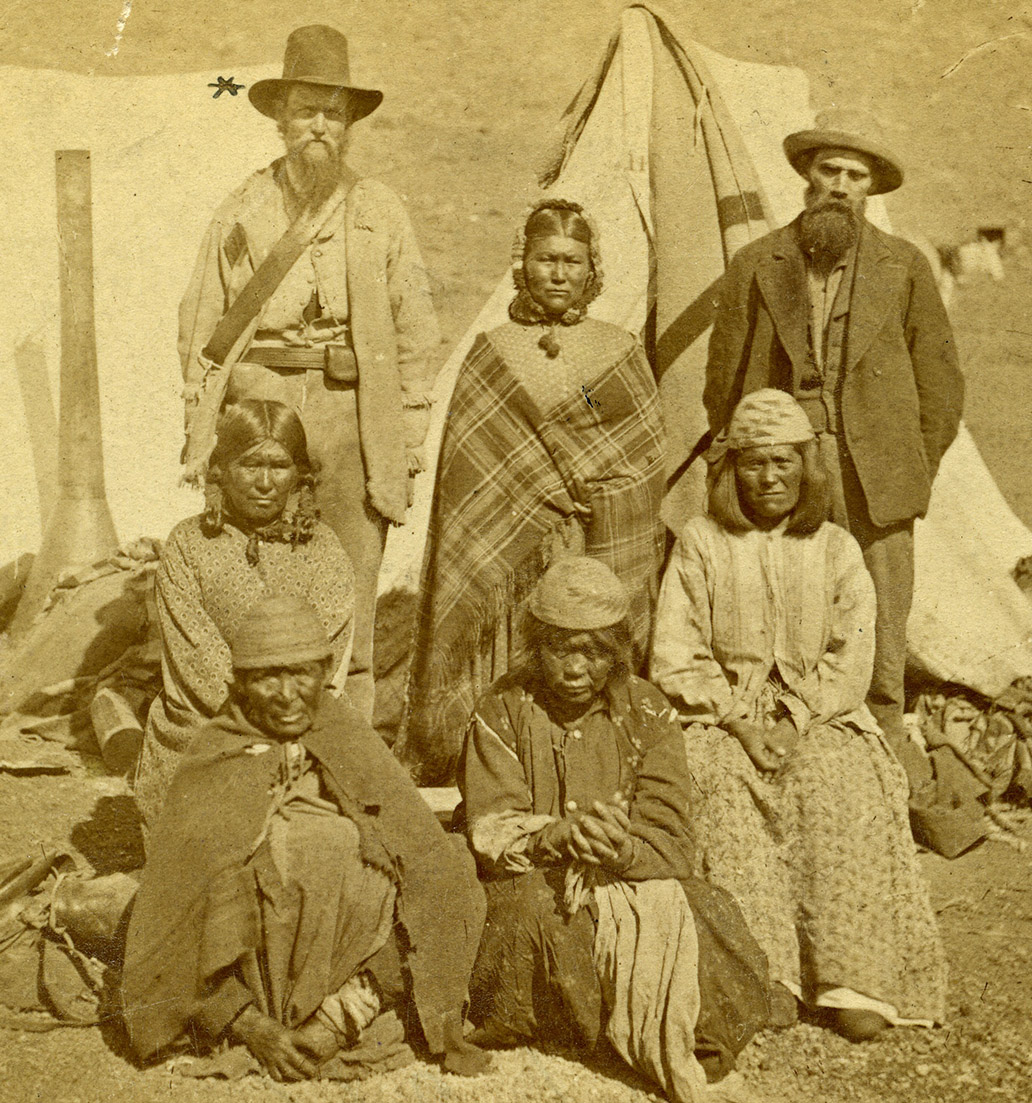

In March 1873, churchmen, military men, and interpreters accepted the responsibility of securing peace in a troubled land. The commission was made up of Alfred Meacham, Leroy Dyar, Rev. Eleazar Thomas, Gen. Edward R.S. Canby, and Winema and Frank Riddle. The commission's main goal was to meet with the Modocs and induce them to return to the reservation and turn the killers over to the authorities.

General Canby early on recognized the Modocs' concerns on the reservation. In 1872 he related that when the Modocs had settled on the reservation, they "were so much annoyed by the Klamaths that they complained to the local agent [Knapp], who, instead of protecting them in their rights, endeavored to compromise the difficulty by removing them to another location." His perception, however, did not solve the Modocs' discontent. One year after he made this statement, Canby found himself in the middle of a war that resounded throughout the United States and that ultimately took his life.

The history of the war and the peace commission can be found in numerous House and Senate reports. For example, House Report 1413 of the 50th Congress focuses on details of Winema's actions as she sought peace between her people and the U.S. Government. Of particular interest is her interaction with the Modocs in the Lava Beds. Between February 20 and April 11, 1873, Winema and her husband served as mediators, often under dangerous circumstances. According to the report, the Modocs in the Lava Beds learned of the U.S. desire for a meeting with the newly formed peace commission and sent Bob Whittle and his wife, Matilda (an Indian woman), with a message asking for the Riddles and John Fairchilds to act as intermediaries. They believed this meeting would allow "Riddell and Fairchilds to conclude details."

As a result, Winema traversed the Lava Beds to help bring an end to hostilities. Her role as messenger and mediator emerged for several reasons. She had working knowledge of both the Modoc and English languages; as a woman, her presence represented peaceful intentions, allowing her fluid movement in carrying messages between camps; and as Kintpuash's relative, she fell under his protection when she was in the Lava Beds. She visited the Lava Beds several times, often being threatened by the more hostile Modocs who were suspicious of her and her connection to the peace commissioners, but Kintpuash saw to her safety.

The Modocs, after seeing the entrenchment of the military, could foresee no way to stop the war, but they did express to Winema their willingness to meet with the commission and negotiate a peace. On March 9 she, along with Rosborough, Steele, and her husband, encouraged Kintpuash to meet with Canby and the other commissioners to determine a time and meeting place. On March 27 the Modocs related through Winema that they would settle for a reservation in the Lava Beds; Canby replied that he had no power to grant their request but that they should meet to determine a peaceful solution. Nothing came of these exchanges; the two sides did, however, agree to meet again in mid April.

The knowledge Winema brought back to the peace commission would not keep either the Modocs or the commissioner free from danger. During her last visit to the Lava Beds in early April, as she left to bring information to the peace commissioners, Wieum, one of Kintpuash's followers, went after her to inform her of a plan to kill the peace commissioners. She took this news to Canby and Meacham. Canby disregarded her warning and still insisted on meeting with the Lava Bed Modocs. Meacham urged Canby to listen to Winema. The meeting was set for Good Friday, April 11, 1873.

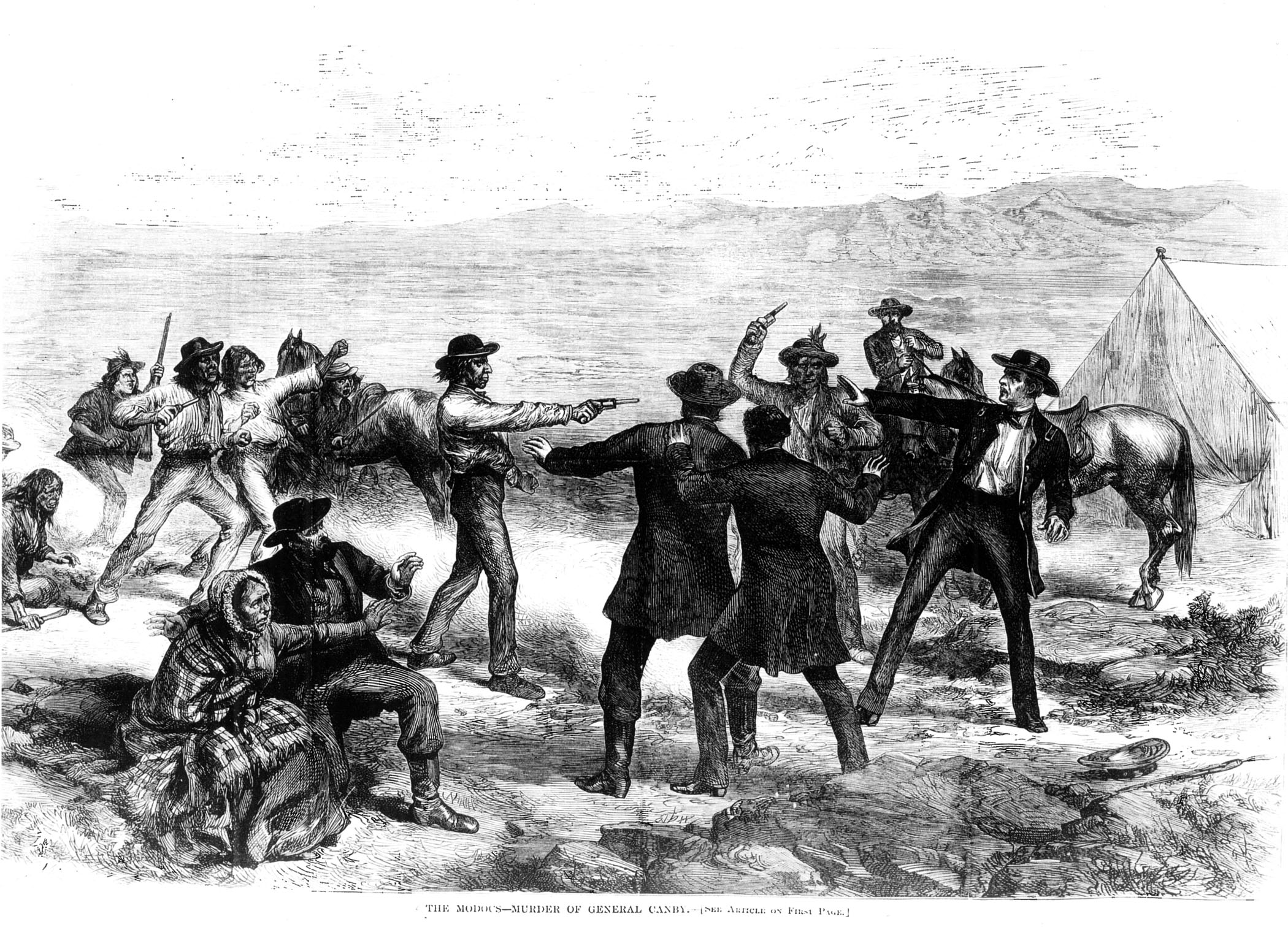

Winema's many warnings to Canby and Meacham of the Modocs' intentions created tension among the peace commissioners. On the morning of April 11, Winema was determined to make Canby listen to her, but he refused to heed the warnings. She then turned to Meacham and pleaded with him not to go. When he told her it was his duty, she physically tried to stop him from following Canby. Because he had final say in the negotiations, Canby proceeded to the meeting place where six Modoc men awaited the commissioners.

Kintpuash had been pressured into killing the commissioners, but once the meeting began, he tried to again to negotiate a place for the Lost River Modocs in California. However, the purpose of the commission was to have the Modocs surrender, to give up the killers of the settlers to authorities, and to move back to the Klamath Reservation. When the council started, Canby refused to listen to Kintpuash's reiteration of his request for a home in the Lava Beds. Canby's refusal and his demand for their unconditional surrender sealed his fate; Kintpuash could not give up his people to Canby's justice. Throughout the exchange between Canby and Kintpuash, Winema tried to keep tempers at bay, but even she realized the futility of negotiation at that point. When Kintpuash realized that the meeting was one-sided, he and the other Modocs opened fire on the peace commissioners.

In the ensuing skirmish, Canby and Thomas died; Dyar and Frank Riddle escaped. Meacham was severely wounded and, had it not been for Winema, would have died. As one Modoc man, Shacknasty Jim, started to strip Meacham of his clothing, another, Boston Charley, wanted to be sure Meacham was dead. Shacknasty Jim, however, told him that Meacham was already dead. Boston Charley then proceeded to scalp Meacham, when Winema stepped in and started yelling that the soldiers were coming. Risking her own safety, she saved Meacham's life. The act bound Meacham and Winema as friends forever. The killing of the peace commissioners made national and international news. For the Modocs it meant two more months of fighting and eventual surrender as the army closed in.

For a month and a half after the attack on the peace commissioners, the army besieged the Lava Beds. Because the Lava Beds are a natural fortress, 159 Modocs, mostly women and children, were able to maintain an advantage over a thousand troops for several months. However, as negotiations soured and the army sought vengeance for Canby's death, it had ample time to figure out how to penetrate the Lava Beds. Eventually, the soldiers found ways to get closer to the caves, and the Modocs lost their tactical advantage. By the time troops had reached the encampment, the Modocs had already escaped, dispersing as they fled. According to Lt. William Henry Boyle, a veteran of the Modoc War, the Modocs did not surrender as one group, and, as the army closed in, they knew they were no match for the advancing soldiers. Kintpuash's party was the last to surrender. Boyle claimed, "Captain Jack surrendered at 10:30 a.m., June 1, 1873, saying that his legs had given out. The costly Modoc War was over."

The conclusion of the war did not bring Winema and Frank's roles to an end. When the military accompanied the Modocs back to Fort Klamath, all 159 Modocs who had encamped in the Lava Beds were confined in the stockade, where they awaited their fate. A trial of six Modocs—Kintpuash, Schonchin John, Boston Charley, Black Jim, Barncho, and Slolux—ensued. Winema and Frank Riddle were witnesses at the trial and, when called upon, testified about the events surrounding the war and why the Modocs had acted as they did.

On July 1, 1873, after a speedy trial, Judge Advocate H. P. Curtis passed sentence on the six Modoc men, who were to "be hanged by the neck until [they] be dead." Four death sentences proceeded; Kintpuash, Schonchin John, Boston Charley, and Black Jim were hanged on October 3, 1873. Because Barncho and Slolux's participation in killing Canby were in doubt, the judge reduced their sentences to life imprisonment on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay.

After the war ended, the lives of many Modocs changed dramatically. The 153 Modocs imprisoned at Fort Klamath waited expectantly for their judgment. It came in the form of removal. The federal government removed 39 men, 54 women, and 60 children to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The consequences of the Modoc War directly influenced the makeup of the Modocs as a nation. The Modocs in Indian Territory suffered through this tragic removal and a steady decline in population. In contrast, the Modocs in Oregon suffered a different shift in survival strategies.

Population numbers in Oregon differed tremendously from those in Indian Territory. In 1874 the Modoc population numbered approximately 200 and remained relatively stable into the early 20th century. Although many intermarried with people from other native nations on the Klamath Reservation, tribal designation continued through the father's line. Census records indicate names that reflect those Modocs who remained on the reservation before and during the 1870s. Old Chief Schonchin and his family consistently show up on the rolls well into the 20th century. Similarly, the census rolls for the Klamath Agency list Toby Riddle, Modoc Billy (name changed to William Hardin), Modoc Charley (name changed to Charles Modoc Faithful), and several other Modocs who raised their families there as well. After Jeff Riddle established his family, his mother's and father's names appear in conjunction with Jeff's. They are listed in terms of their relationship with their son; this indicates that the Klamath Agency regarded Jeff as the head of household. Overall, the Modoc population in Oregon remained steady. Those Modocs in the Indian Territory held their status as Modocs under the Quapaw Indian Agency and maintained cultural norms as they adapted to the new area despite their population decline.

Immediately after the war, Winema and Frank decided that they could further serve Native Americans by bringing attention to the Modocs' plight. At Meacham's urging, they embarked on a lecture circuit, speaking about what had happened during the war and how Winema had saved Meacham's life. The Riddles traveled throughout the United States, going to large cities such as New York. This endeavor, however, came to a quick end as Meacham and the Riddles could not afford moving from place to place. In addition, being away from her people and home took its toll on Winema. She became very homesick, and Frank feared for her welfare. He wrote to Oliver Applegate, subagent of the Klamath Reservation, several times, asking to borrow funds to get them home. Eventually they did return to the Klamath Reservation, where both lived out the rest of their lives.

Meacham and Winema forged a lasting friendship that withstood the ravages of war, the failure of a lecture tour, and the devastation of sickness and death. Because of Meacham's deep respect for Winema and her role in the war, he insisted that she receive a military pension and determinedly petitioned Congress to make it so. He wanted public recognition of Winema's courage in saving his and other lives during the conflict between the Modocs and the peace commissioners on April 11, 1873. By special act of Congress, pension certificate number 565101 was issued to Winema Riddle. The act noted that the pension of "$25 per month" was granted "for service rendered Commission to the Modoc Indians."

Winema became one of the few women to receive a pension by a congressional act. This recognition acknowledged Winema as a key participant during peace and war, solidifying her role as a mediator between cultures. Winema received the monthly sum of $25 until she died of influenza in 1920. Her son Jeff asked the Pension Office for the remainder of her pension for February of that year to "pay Mother's funeral expenses."

Winema's death marked the closing of an era—she was one of the last Modoc War participants to die, and she was one of the first American women to be distinguished by congressional act for her actions in time of war. More important, she instilled in her son the significance of diplomacy and what it means to be a leader. She merged the two concepts as mother and mediator. Jeff later became a councilman and judge for the Modocs living in Oregon.

Her actions in the events unfolding in northern California drew the respect of many, including some who solely blamed the Modocs for the hostilities of the 1870s. For example, in 1909 Oliver Applegate wrote about the importance of her role in the war and in securing peace. He contended that if Canby had listened to and followed Winema's counsel, he and the others would not have lost their lives on that fateful day. He wrote, "She was courageous and intelligent and had her counsel been taken, the bloody Peace Commission massacre would not have occurred."

Note on Sources

Uncovering sources and information about Native American women is a challenging endeavor to say the least. It is remarkable that a plethora of sources shedding light on one woman's life can be found in the National Archives. Winema's legacy is recorded in government documents, congressional records, pension files, her own testimony, and in a biography that praises her courage and acknowledges her role in historical events of the 19th century. In a general sense, her story and the sources that include it give us insight into the Modoc Nation and Native American issues in terms of women's roles and participation in their own societies. In an individual sense, Winema made history and influenced events that directed Indian policy and Indian-white relations into the 20th century.

The National Archives holds many different sources pertaining to Modoc history and Winema's life. Of particular interest is Winema's military pension file, certificate number 565101. This file contains both Winema's pension papers and her son's correspondence with the Pension Office about Winema's death. Much can be gleaned from the letters included in Letters Received from the Oregon Superintendency of Indian Affairs, 1848–1873 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M2), Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group (RG) 75, about events and times surrounding Winema's childhood, especially the issues surrounding the settlement of northern California and southern Oregon. Also contained in these letters is correspondence on the functioning of the Klamath Reservation, including events leading up to, during, and after the Modoc War.

Because the Modoc War tends to be the central issue that concerned the federal government in relation to the Modocs, the Office of the Adjutant General kept thorough records in a separate file on the war in Selected Consolidated Files pertaining to Indians in the Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General (Main Series), 1871–1880 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M666, rolls 20–22), Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94, Letters Received, File Number 2418 AGO 1871. More information can be found specifically on the Modocs' experiences on the Klamath Reservation and field reports on the actual fighting taking place at the Lava Beds in Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, RG 393, Geographic Districts: Pacific Northwest Area, District of the Lakes.

Congressional records also contain detailed information on the Modocs' interaction with the Klamath Agency, Winema's participation in the war, and the war itself. Of particular interest are the following reports: U.S. House of Representatives, 33rd Cong., 1st sess., Rept. 133; U.S. Senate, 42nd Congress, 3rd sess., Ex. Doc. 201; U.S. House of Representatives, 43rd Cong., 1st sess., Ex. Doc. 122. Further detailed correspondence is housed in the Special Collections, Knight Library, University of Oregon, Eugene, under the Oliver Cromwell Applegate Papers and Lindsay Applegate Papers. For the Modocs' removal to Indian Territory, see Quapaw Agency Reports, housed at the Oklahoma Historical Society in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

An excellent source on Winema and her life is Alfred Meacham's Wi-ne-ma (The Woman-Chief) and Her People (Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company, 1876). Meacham includes Winema's personal history, her role in the war, her heroic act of saving Meacham's life, and the war in general. For a Modoc perspective on the war, see Jeff C. Riddle (Winema's son), The Indian History of the Modoc War (San Jose, CA: Urion Press, 1974). Keith Murray's The Modocs and Their War (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959) gives a detailed account of the war. The war ended with the trial six Modocs; the entire transcript of the trial can be found in Guardhouse, Gallows, and Graves: The Trial and Execution of Indian Prisoners of the Modoc Indian War by the U.S. Army, 1873, compiled by Francis L. Landrum (Klamath Falls, OR: Klamath Country Museum, 1988): appendix B. Winema testified at the trial—this is perhaps the only written source of Winema's actual words.

Census material also gives insight into the population numbers both in Oregon and the Indian Territory. Winema is listed on the Klamath Rolls until her death in 1920. See Indian Census Rolls 1885–1940 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M595): Klamath (Klamath, Modoc, Paiute or Snakes, and Pit River Indians).

Rebecca Bales is on the history faculty at Diablo Valley College in Pleasant Hill, California. Her field of specialization is Native American history with an emphasis on women. Her current research focuses on Native American women in California, and her publications include articles on that subject.