Native Americans in the Antebellum U.S. Military

Winter 2007, Vol. 39, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By James P. Collins

Mentioning the U.S. military and American Indians together often brings to mind fierce and heart-wrenching battles between white soldiers and native warriors. But is this the whole picture? A review of selected records for soldiers who served during the Indian wars and disturbances from 1815 to 1858 shows that hundreds of Indians served in the military against their fellow Native Americans. In addition to serving in these wars, Native Americans served during the Revolutionary War and throughout the 19th century, almost exclusively in all-Indian units.

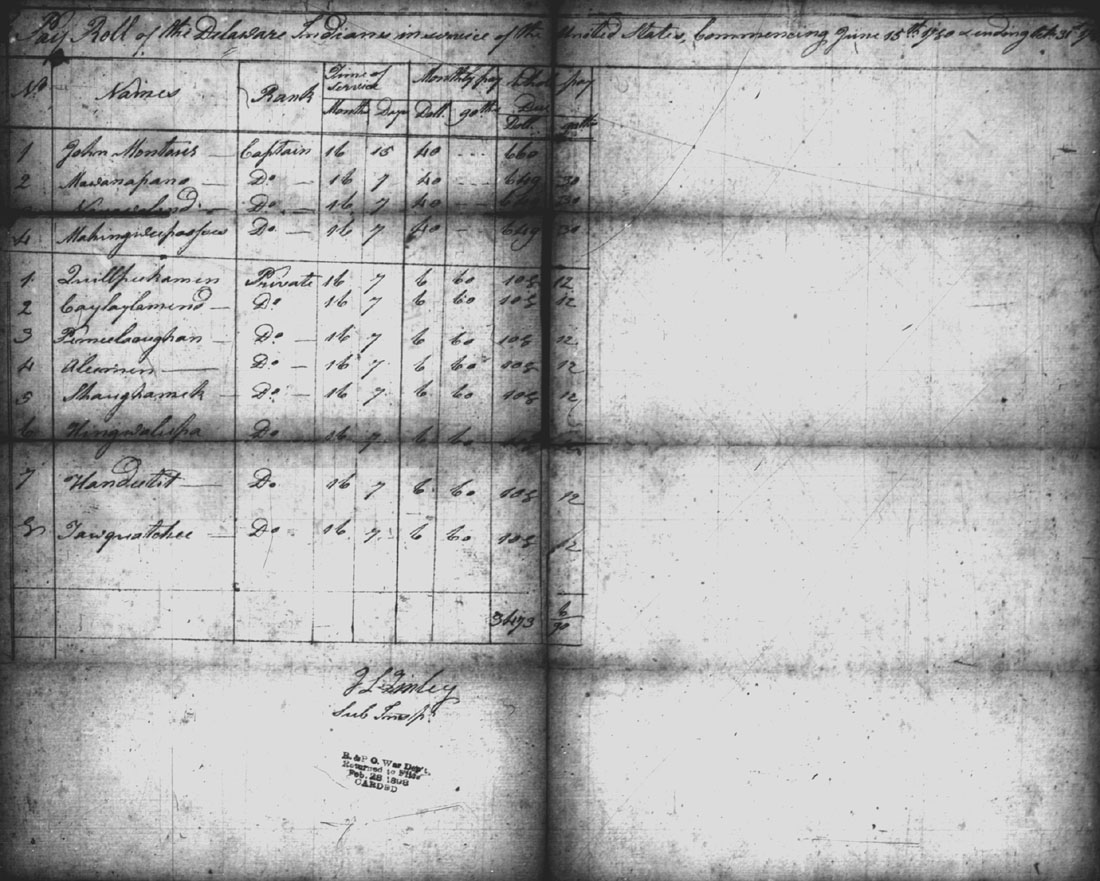

One Native American unit appears among the military records of the soldiers who served in the Revolutionary War. The "Pay Roll of the Delaware Indians in service of the United States, Commencing June 15th 1780 & ending Oct. 31, 1781" lists 12 soldiers: 4 captains and 8 privates.1 The names, except for Capt. John Montour, the company commander, appear to be in the Delaware language. For example, Captain Mawanapano is the second soldier listed after Captain Montour.

Compiled military service records are also available for these soldiers.2 The War Department abstracted a volunteer soldier's service onto cards from such records as muster returns and payrolls. The cards were placed in an envelope with the soldier's name on it.

Between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, one Native American unit served with federal forces. Capt. Will Shorey commanded the Corps of Cherokee Indians, who were in service from May 12 to September 12, 1800. On March 7, 1800, the secretary of war ordered the unit to be formed. Its mission was to punish offenders in the Cherokee Nation. The unit's Records of Events cards do not specify the offenses.3

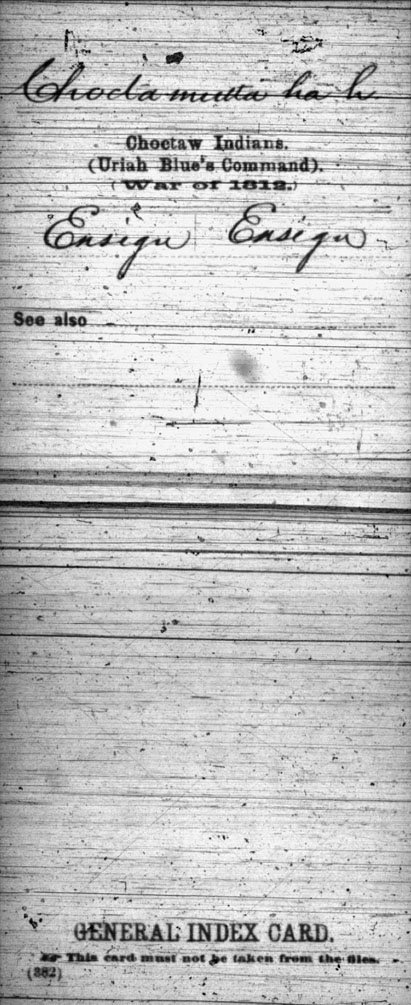

More than 1,000 Native Americans served during the War of 1812. They were organized in more than 100 companies, detachments, or parties. About half were Choctaws, and half were either Creeks or Cherokees. Units from other tribes included Blue's Detachment of Chickasaw Indians (discussed below), Capt. Wape Pilesey's Company of Mounted Shawano Indians, and Capt. Abner W. Hendrick's Detachment of Stockbridge Indians.

Native American soldiers are listed in the Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the War of 1812 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M602). The compiled service records for only two Native American units have been microfilmed: Major Uriah Blue's Detachment of Chickasaw Indians (M1829) and Major McIntosh's Company of Creek Indians (M1830). Both Blue's Detachment and McIntosh's Company served under Andrew Jackson in the Creek Indian War of 1813–1814, sometimes considered a part of the War of 1812.

Researchers should keep in mind the potential variations of Native American names. A selected review of the index and a review of the compiled service records for two War of 1812 units indicates that the majority of Native American soldiers retained their Indian-language name. In Blue's Detachment, for example, Corporal Tush wa tubbee and Private Ush o ma tubbee appear on a muster roll dated February 28, 1815, at Mobile. Other names appear to be the English translation of the Indian name, such as Private Wait & Kill it, who also appeared on the February 28 muster roll. When a common English name is listed in the index, often only a single English name appears. Four Private Georges and a Sergeant George were listed as part of Colonel Morgan, Jr.'s Regiment of Cherokee Indians, and two Private Jims were part of Col. Thomas Gales's Indian Corps.

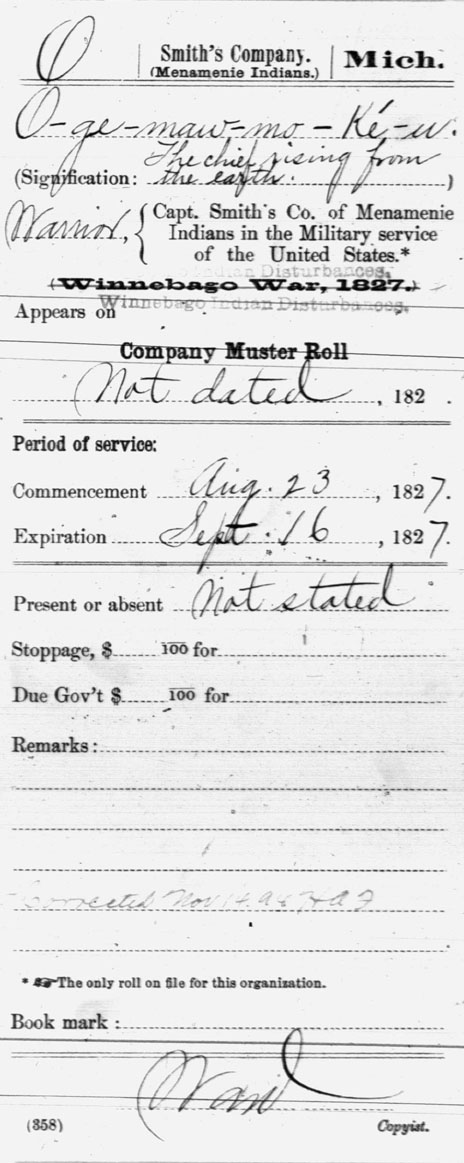

Native Americans served in a majority of the Indian wars that took place from 1815 to 1858. Choctaw and Creek Indians served in the First Seminole War, 1817–1818, and the Second Florida or Seminole War, 1836–1842. During the Winnebago Indian Disturbance in 1827, a company of Menominee served. Menominee and Potawatomi served during the Black Hawk War in 1832. Creek Indians friendly to the U.S. government opposed their fellow Creeks during the Creek War in 1836. These Native American soldiers are listed in the Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Indian Wars and Disturbances, 1815–1858 (M629).

Captain Smith's Company of Menamenie (Menominee) Indians served in 1827 during the Winnebago Indian Disturbances. The compiled service records for this unit list 125 men, nearly all designated with the rank of "warrior."4 There was also a "1st Chief," "War Chief," and two "Chiefs." All names appear to be in the Indian language, and many have the English translation. Warrior Eyam-e-taw's name, for example, translates to "The raw deer skin." A few muster roll cards show familial relationships among the soldiers.

Capt. Stephen Richards's Company of Friendly Indians made up part of the Florida Mounted Volunteers, which served in 1838 during the Second Seminole War. The compiled service records of volunteers who served in Florida units during the Florida Indian wars, 1835–1858, including Captain Richards's Company, have been microfilmed.5 No rank is noted for the men, although Tot-tour-Hargo is listed as "Capt. Billy." A few names, such as Madison and Isaac Yellowhair, are not in the Indian language.

One company of Native Americans served in the Mexican War, 1846–1848. Black Beaver's Spy Company was a mounted volunteer company of Indians from Texas. The compiled service records for all Texas units, including Beaver's Spy Company, are on microfilm.6 The members of the company mustered in for duty in San Antonio in June 1846 for six months. The names of privates Na-noon-ska-ska, Long Tail, and George Williams, show the mix of the Indian language, English translation of the Indian name, and an English name.

Immediately following the Mexican War, a company of Pueblo Indians served with the New Mexico Volunteers. Under the command of Bvt. Lt. Col. J. M. Washington, the Pueblos participated in an expedition against Navajos from August 22 to September 22, 1849. Nearly all the Indian names in the company's service records are Spanish, such as Juan Domingo, Salvador Andres, Francisco Garcia, and Lorenzo Duran, suggesting that many of the Pueblos assimilated themselves into the local Mexican culture. One possibly native Pueblo name, Topan, also appears.

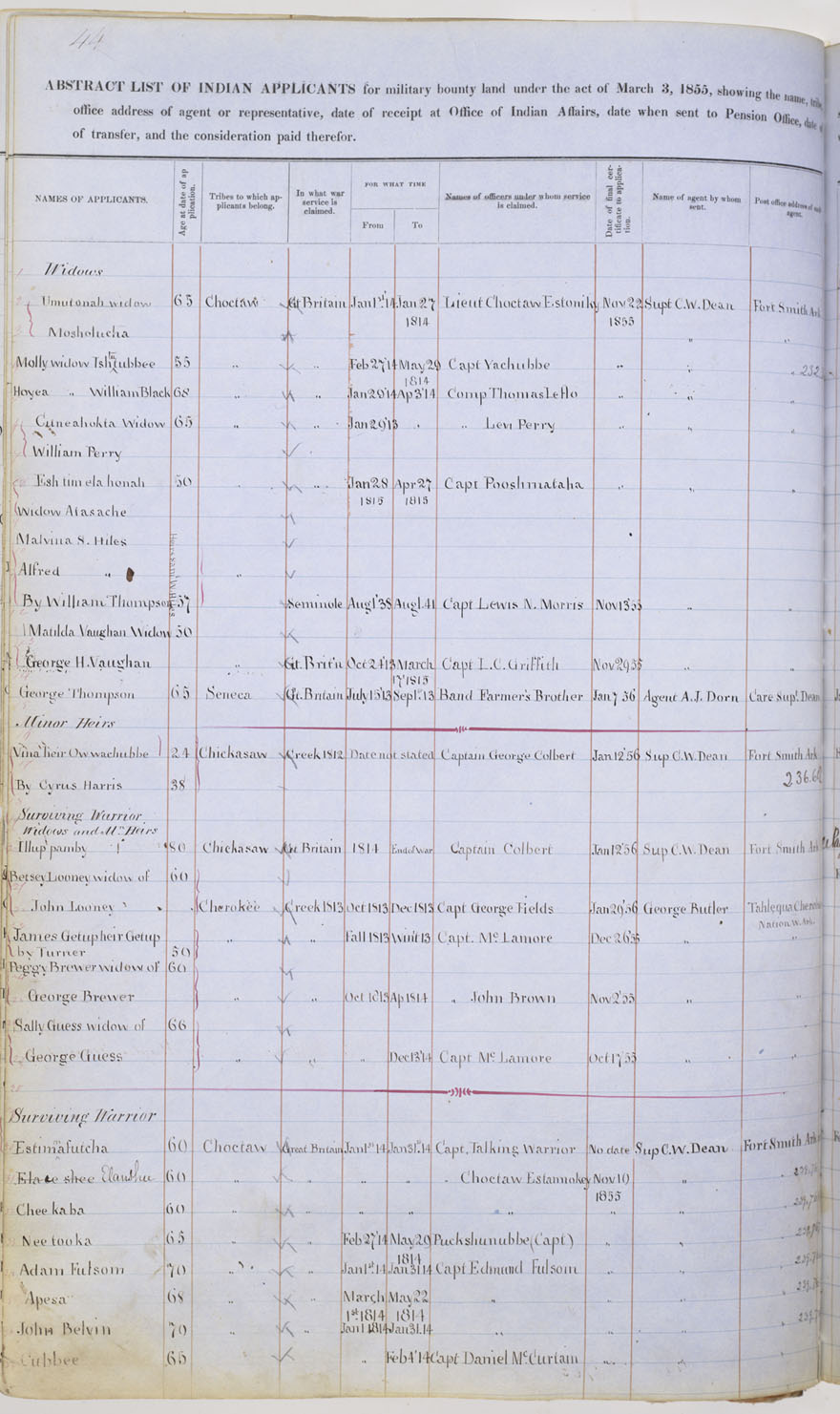

Many Native American soldiers, their widows, or dependents applied for bounty land warrants or pensions, sometimes both, following the soldiers' service. Native Americans became eligible to apply for bounty land by an act of Congress dated March 3, 1855, that granted bounty lands to certain officers and soldiers who had been engaged in military service. Section 7 of this act extended all bounty land laws to "Indians, in the same manner, and to the same extent, as if the said Indians had been white men." Native Americans also applied for pensions under general statutes directed at all veterans of a conflict, such as "An Act granting Pensions to certain Soldiers and Sailors of the War of 1812, and the Widows of deceased Soldiers" passed on February 14, 1871.

Among the records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs is a unique resource for identifying Native Americans who received bounty land warrants. The bureau required its agents to take steps to protect Indians from being swindled by unscrupulous people during the bounty land application process. One step was to keep a register of the issuance and transfer, if applicable, of the warrant. The name of each soldier, widow, or dependent was entered alphabetically by the first letter of the surname, along with the age and tribe of the applicant, the war, service dates, and the soldier's commanding officer. The remaining 12 columns provide information on the issuance and disposition of the warrant. This information usually is sufficient to request the bounty land warrant file at the National Archives. An index to about half the applicants listed in the registers was prepared.7

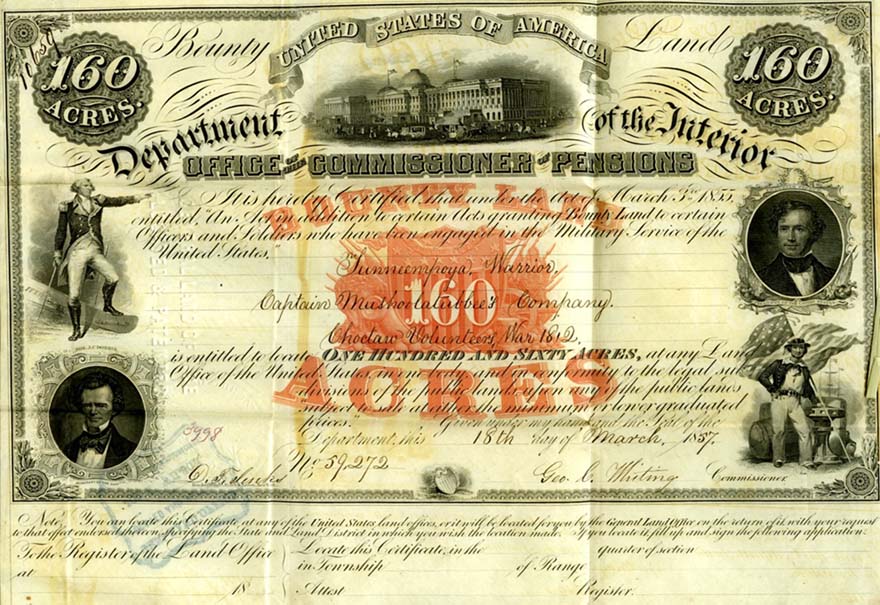

To locate the bounty land warrant files, you will need to know the warrant number, the number of acres received, and the year of the relevant bounty land law. The previously cited 1855 bounty land law is the law that authorized Native Americans to apply. The warrant number and usually the number of acres can be found in the Bureau of Indian Affairs registers and sometimes in a pension application file. A bounty land warrant file normally contains the bounty land certificate and the transfer of ownership document. Tunneempoya, for example, a warrior in Captain Mushoolatubbee's Company of Choctaw Volunteers during the War of 1812, received 160 acres on March 18,1857. On January 1, 1858, he sold his warrant for $128 to James L. Woodward of New York, who on April 24, 1858, sold it to Carlos Hall of Douglas County, Kansas.8

Native Americans who applied for pensions based upon War of 1812 service are listed in the Index to War of 1812 Pension Application Files (M313). A review of three of the 102 rolls of this index identified five Native American applicants. The documents and information found therein are typical of what might be found in any pension file. Daniel Two Guns, for example, although unsuccessful in his numerous attempts at obtaining a pension, provided much information about himself on his applications. Rachel Two Guns, widow of Henry Two Guns who was possibly a brother of Daniel, provided important genealogical data, such as her maiden name and tribe, in her unsuccessful application.

Two acts of Congress approved on July 27, 1892, and June 27, 1902, authorized pensions for soldiers or their widows for service in the Indian wars and disturbances. A review of portions of two of the 12 microfilm rolls of the Index to Indian War Pension Files, 1892–1926 (T318) located two Native Americans who applied under the provisions of these acts. The two pension files contained documents similar to those in any Indian war pension file. Ninety-five-year-old Kawashca Ash-Pah yean used the "Declaration of Survivor of Indian War" form to apply for his pension, and Pauline Kash-Kosh-Ka, widow of Mitchel Kash-Kosh-Ka, used the "Claim of Widow for Service Pension of Indian Wars" form for her application. In both cases, however, pensions were not approved because the claims of service in the Black Hawk War could not be verified.

Soldiers who served in the Mexican War could apply for a pension under the provisions of the pension act of January 29, 1887. They are listed in the Index to Mexican War Pension Files, 1887–1926 (T317). A spot-check of 2 of the 14 rolls of this series, and a check for a dozen soldiers who claimed to have served, located one Native American applicant. John Beaver was a Delaware Indian in Black Beaver's Spy Company, but his claim of service could not be verified.

The records described in this article are the primary sources to document the service of Native Americans in the military prior to the Civil War. Historians can use the records to describe the contributions of Native Americans, and genealogists can learn about the service of individual soldiers of interest to them. Pension applications are often rich in genealogical data that may not be available anywhere else. The warrant registers created by the Bureau of Indian Affairs are a unique resource of information about Native Americans who applied for bounty land.

James P. Collins is a volunteer staff aide at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. He has worked on a variety of genealogy-related projects since 1996. He wishes to thank three National Archives staff members for their help with this article: John Deeben, Constance Potter, and Rebecca Sharp.

Notes

1. Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1783 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M246, roll 129), War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group (RG) 93.

2. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War (National Archives Microfilm Publication M881, roll 146), RG 93.

3. Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served From 1784 to 1811 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M905, roll 6), Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94. The Cherokee Indians who served under Capt. Will Shorey are listed in the Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served From 1784–1811 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M694), RG 94.

4. Compiled Military Service Records of Michigan and Illinois Volunteers Who Served During the Winnebago Indian Disturbances of 1827 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1505, roll 3), RG 94.

5. Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Florida During the Florida Indian Wars, 1835–1858 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1086, roll 46), RG 94.

6. Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the Mexican War in Organizations From the State of Texas (National Archives Microfilm Publication M278, roll 16), RG 94. The members of the company are listed in the Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served during the Mexican War (National Archives Microfilm Publication M616), RG 94.

7. Entry 544 (Index to Abstract List of Indian Applicants for Military Bounty Lands, 1855–75), and Entry 545 (Abstract List of Indian Applicants for Military Bounty Lands, 1855–82), Records of Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC.

8. Bounty Land Warrant file 59,272-160-1855 for Tunneempoya, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15, NAB.