Opening the Files on War Crimes

Winter 2007, Vol. 39, No. 4

The government panel charged with declassifying U.S. records on Nazi and Japanese war crimes and war criminals in World War II and the Cold War completed its mission this year after opening more than 8.5 million pages of previously sealed documents.

Much that had not been disclosed previously was caught up in masses of intelligence and investigative records held to protect intelligence sources and methods. The panel, known as the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Interagency Working Group (IWG), took up the challenge of balancing real national security concerns against the commitment to uncover and open remaining records about the Holocaust, Japanese atrocities, and the ultimate fate of suspected war criminals.

"Historians, political scientists, journalists, novelists, students, and other researchers will use the records the IWG has brought to light for many decades to come," wrote Steven Garfinkel, IWG acting chair, in the final report issued in Fall 2007. "The details of major and lesser.known events will now be far richer, and as nuances of these events come to light, historians will reinterpret and revise our previously accepted narratives."

Garfinkel said the IWG's declassification effort, which cost about $30 million, also had another effect, possibly more important than the mere opening of millions of pages of documents.

"It has demonstrated," he said, "that disaster does not befall America when intelligence agencies declassify old intelligence operations records." In the past, he noted, intelligence agencies would "routinely and consistently" keep classified files with information about sources and methods, regardless of how old or how sensitive the information in them was.

World War II stands as the central event of the 20th century in its impact on the lives and memories of its survivors, and interest in the war and the Cold War that followed has remained strong among historians as well as the public.

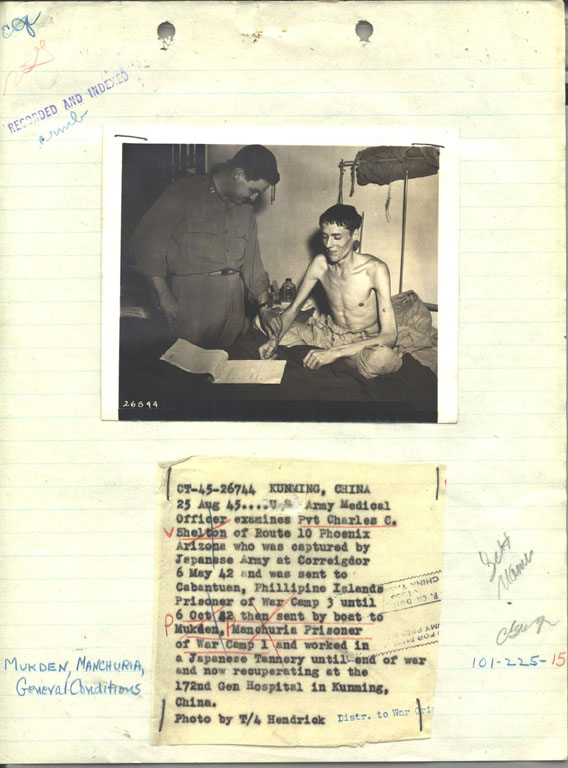

In recent years, Congress took action against war criminals who had managed to take refuge in the United States and to address the Holocaust acts that looted gold, art, and property from its victims. At the end of the century, Congress twice tasked the IWG—first under the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act of 1998 and then by the Japanese Imperial Government Disclosure Act of 2000—to locate and open records in federal custody about World War II war crimes, war criminals, and the victims of crimes and atrocities and to disclose how the government has acted on that information since the war.

The IWG included three public members: Thomas H. Baer, head of Steinhardt Baer Pictures Company; Richard Ben-Veniste, a partner in the Washington, D.C., law firm of Mayer Brown LLC; and Elizabeth Holtzman, former U.S. representative from New York and now an attorney in New York City with Herrick Feinstein, LLP.

In addition, the federal government was represented by the Central Intelligence Agency; the Departments of State, Defense, and Justice; the National Security Council; and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum—all under the leadership of the Archivist of the United States.

Three NARA leaders directed the IWG: Michael Kurtz (1999–2000), assistant archivist for records services—Washington, D.C.; Steven Garfinkel, the retired head of the Information Security Oversight Office (2000–2005); and Allen Weinstein, the current Archivist of the United States (2006–2007). The ongoing work was carried out by more than a dozen government agencies, an international group of historians, and a staff of professional archivists. They spent nearly eight years locating, declassifying, and making available to the public federal records that related not only to World War II Nazi and Japanese war crimes but also shed light on where and how war criminals escaped being charged and punished for war crimes. As a result, records as recent as 2006 have been disclosed under the acts.

The IWG's final report does not seek to present a unanimous opinion by all the members on the declassification efforts, noted Archivist Weinstein. "Instead," he said, "this report presents the larger issues that arose while affording participants an opportunity to present personal or institutional perspectives on issues important to them and to those whom they represent."

The IWG's principal accomplishment was ensuring public access to some long.classified materials, including operational files of the Office of Strategic Services totaling 1.2 million pages; more than 109,200 pages of CIA records; more than 434,000 pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation records; 268,000 pages of records from the Army Counterintelligence Corps; and more than 7 million additional pages of records from the National Archives.

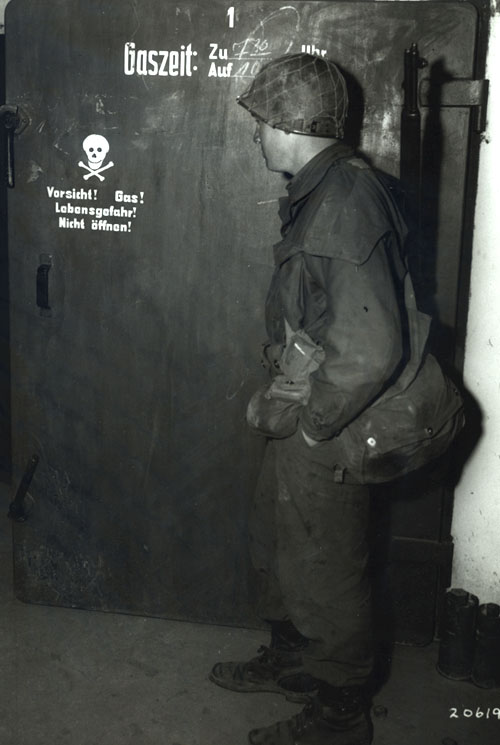

Among the specific records made public are materials on the earliest planning by Nazi Germany for the persecution of the Jews. The OSS obtained foreign diplomatic exchanges in 1941, prior to U.S. entry into the war, disclosing the intention to eradicate European Jewry, but Allied officials did little about it.

"This knowledge seems to have prompted no response on the part of our government," Holtzman said in her statement in the report. Nor, she added, did the United States or Britain do anything when they learned that the Nazis were rounding up Jews for extermination.

The CIA undertook comprehensive searches in its records systems for relevant documents that resulted in the declassification and release of over 1,000 Name and Subject files. Included were "notorious Nazis": Adolf Hitler; Klaus Barbie, the brutal Gestapo leader in France; Adolf Eichmann, a top Nazi official in charge of transporting Jews to concentration campus; Josef Mengele, the doctor who performed human experiments on Jews sent to the camps; Heinrich Mueller, chief of the Gestapo; and Kurt Waldheim, a German intelligence officer who was later secretary general of the United Nations and president of Austria.

More importantly, the files covered former Nazis employed for Cold War intelligence and suspected Japanese war criminals. Most significant may be the files on the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, whose efforts saved over 20,000 Hungarian Jews, and on Amin el Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who collaborated with Eichmann on the destruction of the European Jews.

Details of how U.S. and British intelligence forces used former Nazi intelligence sources after the war as part of their offense in the Cold War against the Soviet Union are also in documents made public by the IWG.

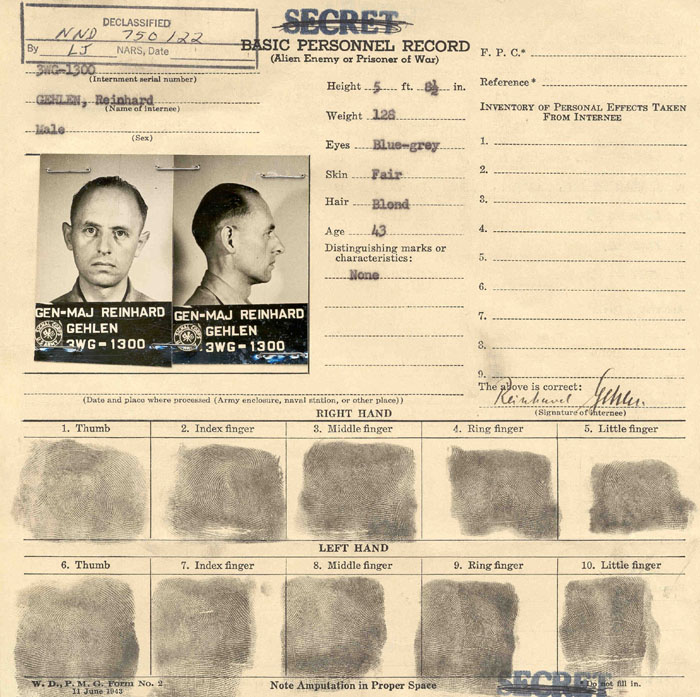

In particular, the final report cites the U.S. Army's involvement with German spymaster Reinhard Gehlen in the postwar period through the mid.1950s. Gehlen had been Hitler's top intelligence officer on the eastern front, but in the postwar era he led an extensive network of spies, some with Nazi and collaborationist backgrounds that made them potential targets of Soviet agents.

"Although some relevant materials have had to be redacted or kept closed, the whole story of American involvement with this intelligence operation that was financed for years by American taxpayers but largely run from Moscow will now be much clearer, as will the screening out of many potential members by more alert American government employees," wrote Gerhard L. Weinberg, chair of the IWG Historical Advisory Panel, former professor of history at the University of North Carolina, and a World War II scholar.

This, Holtzman said, amounted to "collaboration with and protection of Nazi war criminals."

The public members of the IWG—Holtzman, Baer, and Ben-Veniste—also told of the initial reluctance of the CIA to declassify its many records from the post–World War II era. They finally relented after the IWG brought the authors of the legislation creating the IWG—then.Senator Michael DeWine of Ohio and Representative Carolyn Maloney of New York—to a meeting.

Ben Veniste recalled that at the meeting, the CIA repeated its rationale for withholding the documents in question, but DeWine and Maloney rejected the interpretation. "Within 48 hours," he said, "CIA informed the IWG that it would drop its reinterpretation and comply fully with the letter and spirit of the act."

Thereafter, Ben-Veniste said, the CIA "became a 'model citizen' of the IWG, working cooperatively with us to make its relevant records available."

The recommendations in the IWG's final report include calls for:

- adequate funding for declassification efforts in general as well as targeted declassification programs mandated by Congress

- more resources to ensure that declassification is carried out by properly trained staff members

- absolute deadlines for declassification—long ones if necessary

- limitations on targeted declassification projects to subjects of "exceptional public interest" that are not already being addressed by normal declassification programs

- adequate oversight authority to some body for targeted projects

- inclusion of public members, not just agency representatives, on targeted projects.

The IWG's work has opened millions of pages to historians and researchers. Mark J. Susser, a member of the IWG and the historian of the Department of State, said the work of the IWG reflected a renewed recognition by government of the importance of history "and of the importance of paying attention to vital records long overdue for declassification and release."

Susser added: "The process underscored the importance of achieving a balance among legitimate national security issues, legitimate privacy interests of individuals, and the people's desire to know the truth about the atrocities committed by Nazi and Japanese war criminals."

IWG Publications

Historians and associates within the IWG project produced two important publications drawing on newly released records and on the millions of pages of unexploited documents in NARA related to war crimes and war criminals.

U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis (2004), by Richard Breitman, Norman J.W. Goda, Timothy Naftali, and Robert Wolfe, demonstrated the massive potential of the new records to provide answers about the origins of the Holocaust and Allied intelligence use of war criminals following the war.

Researching Japanese War Crimes is a three-part publication consisting of Researching Japanese War Crimes: Introductory Essays (2006), a collection of essays by Edward Drea, Greg Bradsher, and other historians demonstrating the research potential in the millions of pages held by NARA on Japanese war crimes and war criminals; an award-winning electronic version of the 1,600-page Guide to Japanese War Crimes Records in the National Archives, by Greg Bradsher; and an analytical guide to Select Documents on Japanese War Crimes and Japanese Biological Warfare, by William Cunliffe, IWG staff director.

For additional information about the IWG or to request publications, write to iwg@nara.gov.