A Victor in Defeat

Chief Gall’s Life on the Standing Rock Reservation

Fall 2008, Vol. 40, No. 3

By Robert W. Larson

© 2008 by Robert W. Larson

He had been one of Sitting Bull's most trusted lieutenants, with a reputation as a war leader that almost rivaled his famous mentor. They had fought together at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain in Dakota Territory in 1864, and again in 1876 at the Battle of Little Big Horn, where they wiped out five cavalry companies under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

Now, those days were just memories as Chief Gall and his band of hungry and forlorn warriors were led by U.S. Army forces to Fort Buford in North Dakota—having surrendered on January 2, 1881, at the Battle of Poplar River in Montana. The trip took them through deep snow and temperatures as low as 28 degrees below zero.

At Fort Buford, they would stay encamped for five months until they were transported by steamer down the Missouri River to Fort Yates, the military post and headquarters for the Standing Rock Agency in present-day North Dakota.

When Gall, known for his intransigence toward the U.S. Army and white settlement, finally arrived at Standing Rock on May 29, 1881, he still showed signs of that deep-seated bitterness that characterized his months at Fort Buford. After a relatively short time, however, this Lakota war leader began to accept his status as an agency Indian no longer free to hunt and roam throughout the Upper Great Plains.

A key factor in his change of heart was the appointment of Maj. James McLaughlin as Indian agent at Standing Rock. Indian agents at that time were often given the title major. McLaughlin, who arrived three and a half months after Gall did, would make a big difference in Gall's overall attitude.

Throughout much of Gall's early life, he had been controversial because of his strong streak of independence, but McLaughlin would not only make him a more cooperative Indian but would regard him as the chief leader of all the Indians at Standing Rock—the Blackfoot Lakotas and the Yanktonais Sioux as well as his own tribe, the Hunkpapas. These were the wards of the federal government at Standing Rock, which in 1881 was an agency on the Great Sioux Reservation.

Before Gall came to Standing Rock, he and Sitting Bull were regarded as two of the most prominent war leaders of the Lakota tribes of the north. They both played crucial roles in slowing the survey of possible routes for the federally subsidized Northern Pacific Railroad through the Yellowstone Valley in Montana during the U.S. Army's Yellowstone expeditions of 1872 and 1873. Sitting Bull, who was nine years Gall's senior, confined his leadership activities at the Little Bighorn to exhorting the Lakota warriors and their Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho allies to retaliate for the surprise attack on their encampment by Seventh Cavalry troopers. But the 36-year-old Gall was actively involved in the fierce fighting of that fateful battle.

Gall was born along South Dakota's Moreau River in 1840, not far from what would become the Standing Rock Reservation decades later. His early life was spent among hardworking Hunkpapas in a small band that wandered the Dakota plains in search of buffalo. Because he lost his father at an early age, he was raised by his mother, Cajeotowin, or Walks-with-Many-Names.

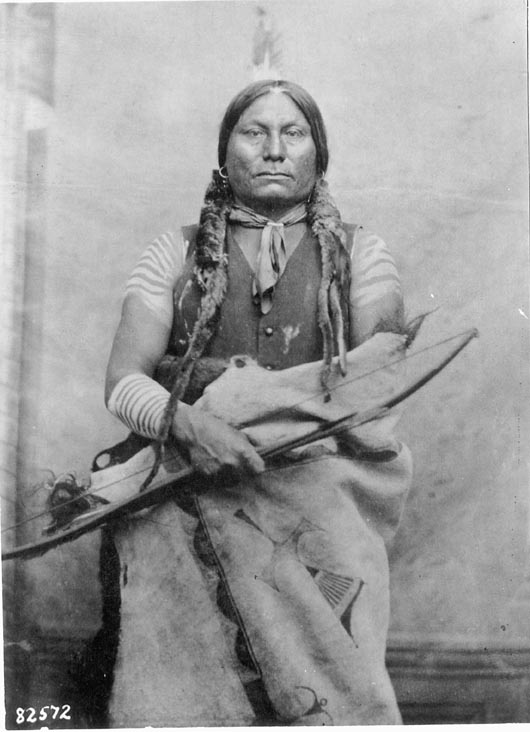

Under ordinary circumstances, the loss of a father would be difficult for a boy growing up in a warrior-hunter culture such as the Lakota Sioux and other Plains tribes. Gall was able to overcome these disadvantages with the help of kinfolk and become a competitive and athletic youth whose self-confidence was abetted by his impressive physique. Although as an adult he only reached five feet, seven inches in height, his muscular arms and barrel chest made him a formidable opponent in battle. His appearance was so striking that Custer's wife, Libbie, who had little reason to like or admire him, remarked, when looking at a photograph of him, that she had never in her life "dreamed there could be in all the tribes so fine a specimen of a warrior as Gall."

As a young man who showed much promise, Gall attracted Sitting Bull's attention. His ability to excel in all those sporting events designed to prepare young Lakotas as warriors, such as riding ponies, wrestling, and throwing the javelin, drew him to the chief. Eventually Gall became a great war leader like Sitting Bull, earning coups in fights against such traditional Lakota enemies as the Crows and Assiniboines. One sure indication of Sitting Bull's respect for Gall's fighting prowess was his role in bringing Gall into the prestigious Strong Heart Society, one of those secret warrior policing societies the Lakotas called akicitas.

Although Gall's prominence was chiefly based upon his record as a war leader, he also gained recognition as a band leader, or headman. This position entailed those responsibilities, especially important during peacetime, to care for the members of one's band, or tiospaye. The role of the headman was often equated with that of an itancan, a tribal peace leader, which means a master or a ruler. Gall, however, tended to be more democratic than most headmen.

One major problem faced by the five northern Lakota tribes—the Hunkpapas, Blackfoot Lakotas, San Arcs, Two Kettles, and Miniconjous—was whether to ratify the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. This treaty, largely the result of the Oglala chief Red Cloud's forcefulness, would grant the Lakota Sioux an immense reservation encompassing the western half of South Dakota, plus hunting rights in the Powder River country, if they would give up their nomadic way of life. A majority of the two southern Lakota tribes, the Oglalas and Brulés, approved the treaty with the exception of some prominent leaders like the Oglala warrior Crazy Horse. Those Lakotas reluctant to change their lives in such a drastic way were leery about accepting this new treaty, one of the most generous ever offered by the federal government to an Indian tribe.

At the behest of Father Pierre–Jean DeSmet, a Jesuit priest who had developed good relations with the Indians, these nontreaty Indians sent a delegation of Hunkpapas to a conference to discuss the treaty at Fort Rice in Dakota Territory on July 2, 1868.

Gall, who headed the delegation, took a hard line in addressing the Indian Peace Commission sent to win approval for the controversial Fort Laramie Treaty. He told the commissioners that peace could not be attained unless the "military posts on the Missouri River . . . be removed and the steamboats stopped coming here." Claiming that his people did not want annuities from the federal government, he openly displayed his battle scars to underscore his unwillingness to compromise.

In the end, however, he and his delegation accepted those presents usually offered to Indian negotiators by the government and affixed his mark on the treaty he had just denounced. It is evident that neither he nor Sitting Bull fully understood the binding nature of a treaty in the eyes of the United States Government.

In the mid-1870s, the defiance of those Lakotas who refused to approve and abide by the Fort Laramie Treaty resulted in the government's ultimatum that all Lakotas living and hunting in the Powder River country or on the buffalo grounds of Montana should return to the Great Sioux Reservation in western South Dakota before January 31, 1876.

When many of the nontreaty Lakotas and their allies refused to comply, military expeditions were sent to compel their obedience. Although the Treaty of Fort Laramie had allowed the Lakotas to hunt in the Powder River country, the tensions caused by the controversial Black Hills gold rush were especially disruptive because these hills were located on the Great Sioux Reservation. This crisis, involving both nontreaty and treaty Indians, resulted in the Great Sioux War, which included such major battles as the ones fought at the Rosebud and the Little Bighorn.

The Army's intense pursuit of these Indians forced Crazy Horse to surrender in May of 1877 and bring his followers to Camp Robinson. At about the same time, Sitting Bull, Gall, and their followers were forced to flee to Canada.

Gall and Sitting Bull spent almost four years as exiles in Canada. Gall, who was particularly sensitive to the needs of his band, surrendered six months before Sitting Bull because his people, like most Lakotas in Canada, were near starvation. Gall's decision to surrender and return to the United States caused a serious rift in his relationship with Sitting Bull that never entirely healed.

Gall probably would have remained a sullen and unhappy Indian at Standing Rock if it had not been for Major McLaughlin. McLaughlin, who had previously been the agent at the Devils Lake Agency, was accustomed to working with the Indian factions that often marked Lakota life after these proud people had been forced to give up their nomadic lifestyle. McLaughlin's Sioux wife, Marie Louise, was another asset for the able Indian agent. Both of them believed that the assimilation of Native Americans as small farmers in the nation's white-dominated society was essential for the country's future, a belief strongly embraced by many Americans during the 1880s.

McLaughlin felt that Gall, along with many other Hunkpapa Sioux sent to Standing Rock, could accept this popular notion. Those who did, like Gall and the Blackfoot Lakota leader John Grass, were characterized as opportunists by such traditional Indians as Sitting Bull, who arrived at Standing Rock two years after Gall did.

But Gall was always more pragmatic about life than Sitting Bull, even though he had been just as intransigent in his opposition to white encroachment and Army intervention as Sitting Bull was before their sharp differences over leaving Canada emerged. The more realistic Gall probably saw no other option to reservation life after his humiliating surrender and internment at Fort Buford. As a result, he began to cooperate with the sympathetic McLaughlin, changing his lifestyle and becoming a hardworking farmer.

Many historians have used the term progressive to describe those Indians who were willing to cooperate and the term traditionalist for those who were not. Unfortunately, the dichotomy has sometimes been slanted to characterize the progressives as being Indians willing to change their attitude and behavior in order to curry favor with their Indian agents. A more recent view embraced by ethnohistorians and cultural anthropologists, however, is to regard many of these cooperative Indians as culture brokers or cultural mediators trying to bridge the gap between themselves and federal agents such as McLaughlin.

McLaughlin had two major plans for managing Standing Rock's affairs when he became its agent in late 1881.

One was to encourage the newly arrived Hunkpapas who came with Gall to leave that part of Standing Rock where most of the current Indian population was residing—the more accessible stretches of land along the Missouri and Cannonball rivers close to Fort Yates, Standing Rock's headquarters. McLaughlin persuaded these new arrivals to settle in the western and southern part instead, especially along the Grand River and Oak Creek, where Gall and his family eventually located.

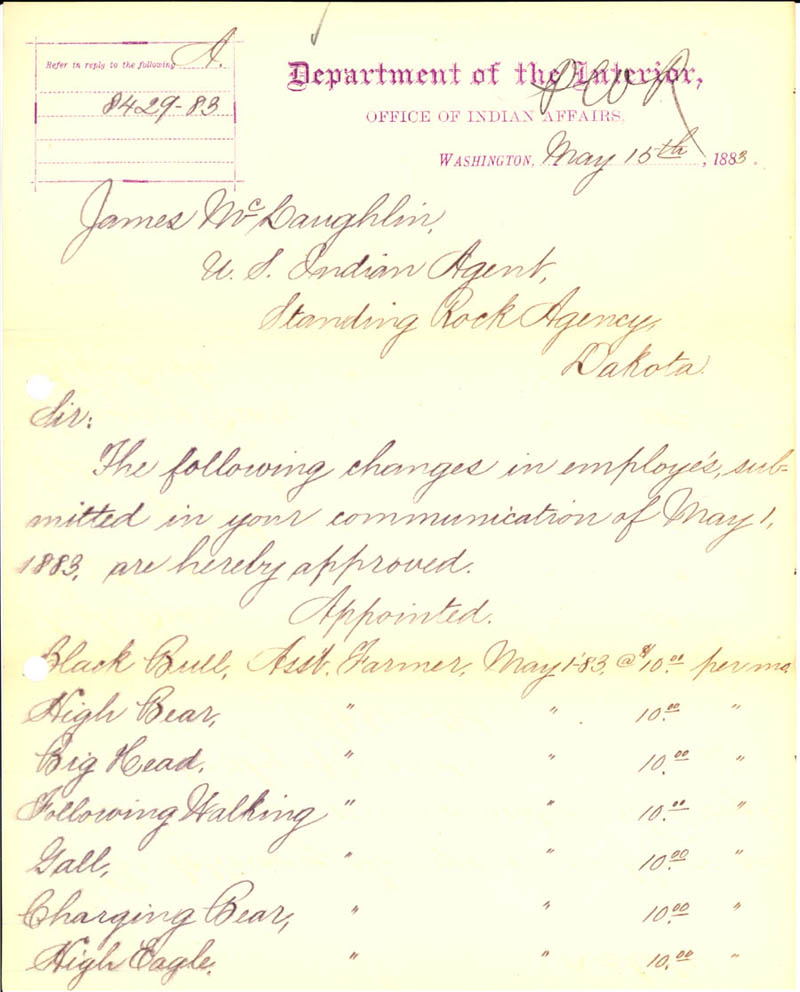

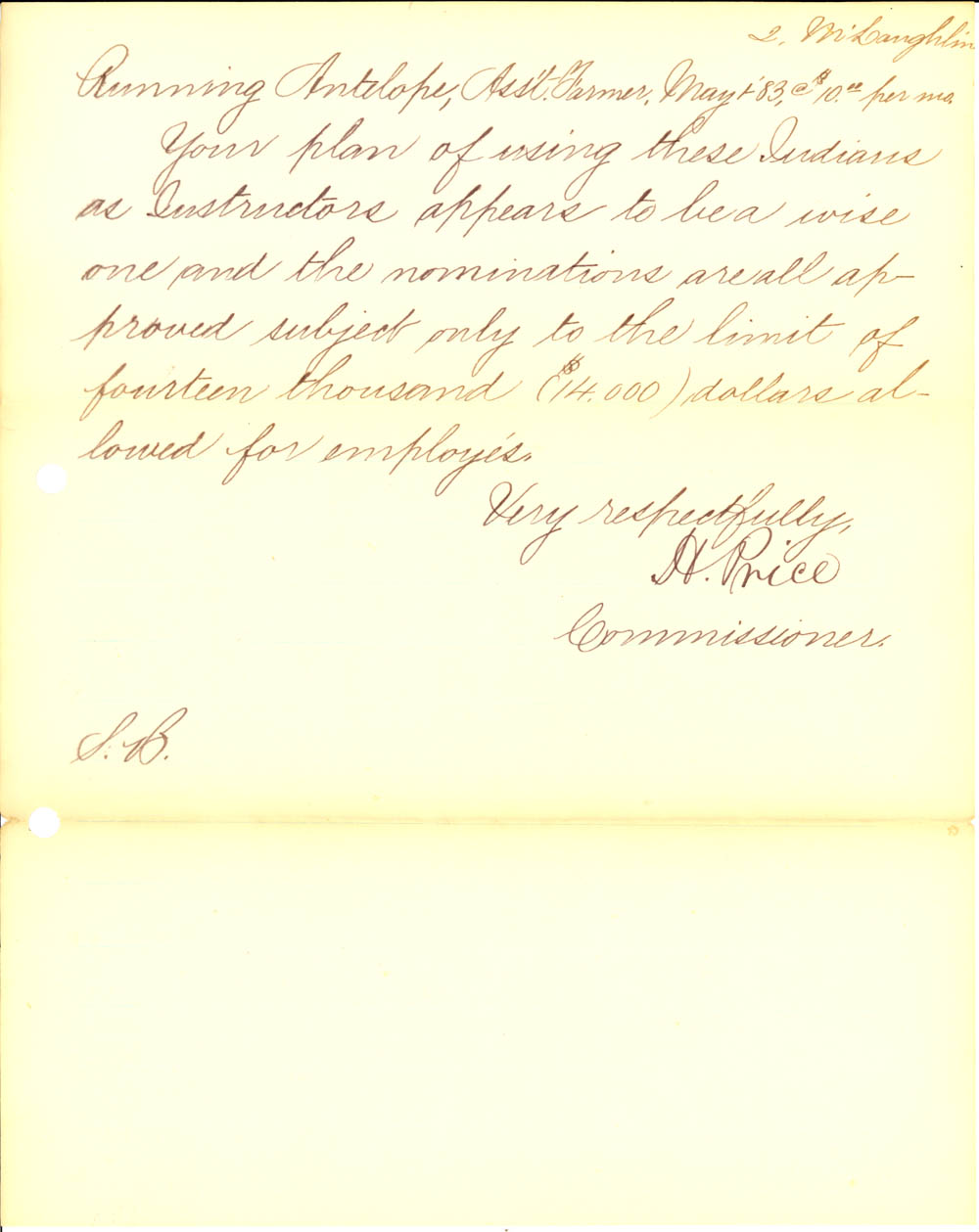

The other plan was to divide the reservation, still an agency in the early 1880s, into 20 farming districts, each of which would be headed by a district farmer, or "boss farmer." The position of assistant farmer was created to provide a necessary backup for the district farmer. During the 1880s these novice Indian farmers would cooperate closely with George Faribault, the head farmer who had been one of McLaughlin's most valuable assistants when he was the agent at the Devils Lake Agency.

Gall managed to fit into McLaughlin's program with remarkable ease. He started out as an assistant farmer at $10 a month on May 15, 1883. On September 4, he was elevated to the rank of district farmer for the fiscal year of 1883–1884. The salary was the same, although as a district farmer his appointment approval letter stated that he would be paid $120 a year instead of $10 a month. The compensation for either rank was not impressive, but the value of U.S. currency was much greater during the late 19th century.

Gall served as district farmer until 1892 with only one interruption, when he resigned to accept an appointment as one of three Native American judges on the Court of Indian Offenses. He proved to be a fair and compassionate judge whose legal perspective reflected the attitude and customs of his people often enough to be overruled on occasions by McLaughlin. After completing his one-year term on the court, he was again appointed as a district farmer in 1890, a position he held until his discharge on December 31, 1892. He probably vacated this responsibility because of failing health, although the murky economy that foreshadowed the Panic of 1893 may also have been a factor.

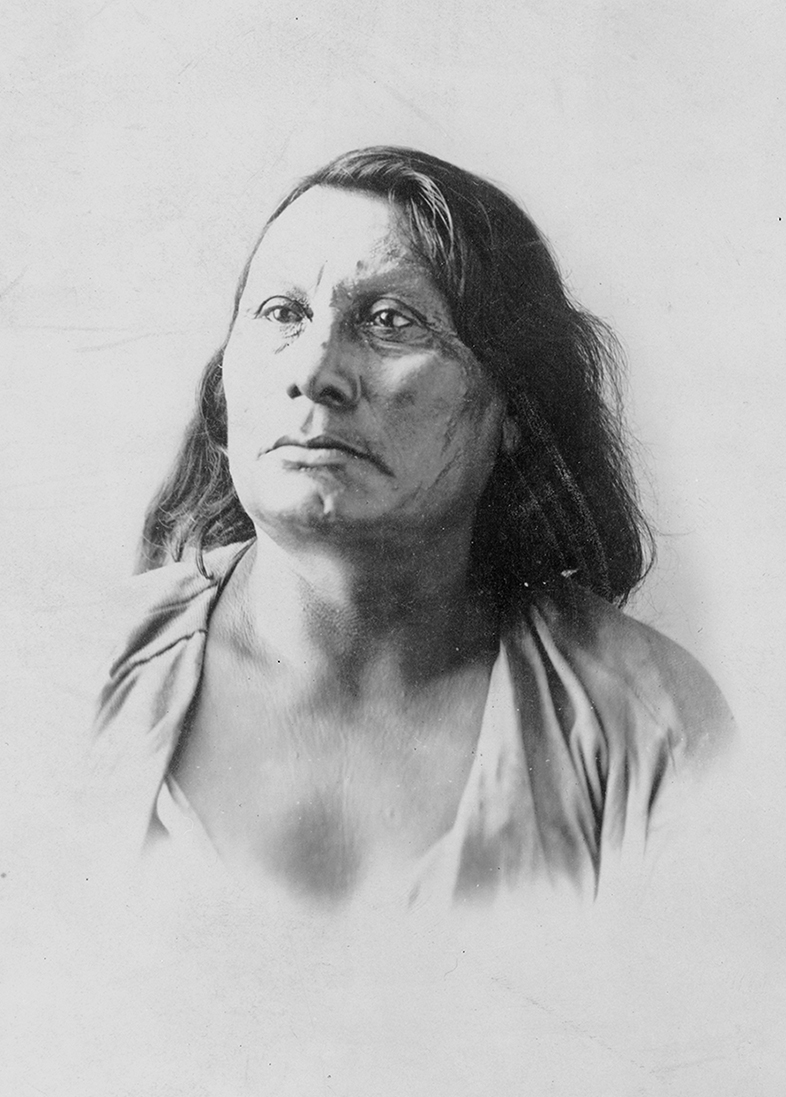

Gall's conscientious service won him McLaughlin's respect. But there were other cooperative Indians who enjoyed a close relationship with McLaughlin. One was Running Antelope, who had been elevated in 1851 to the high rank of shirtwearer of whom there were only four among all the Hunkpapas. He had been an early peacemaker who did not fight against the Army during the Great Sioux War or participate in the long Canadian exile with Sitting Bull and Gall. He served as a district farmer throughout most of the 1880s. Another hero of Little Big Horn, Crow King, would probably have been another close ally of McLaughlin, but he died in 1884.

Although Gall was probably the major's favorite Indian, John Grass was undoubtedly more effective in advancing McLaughlin's program for the assimilation of his Indian charges at Standing Rock. Like Gall, Grass was a district farmer, who served from 1887 to 1889. Also like Gall, he resigned in 1889 to become a judge on the Court of Indian Offenses. Josephine Waggoner, a mixed-blood married to an Army private at Standing Rock, knew both Gall and Grass well and considered Grass to be the best Indian orator she had ever heard. Grass also had a fine mind and worked to persuade McLaughlin to focus more on raising stock than farming as Standing Rock's chief occupation. It was a wise recommendation, given the aridity of the land, and McLaughlin eventually came around to Grass's viewpoint.

With Lakota leaders like Gall and Grass, McLaughlin had invaluable assets in two able men who could advance his assimilation program. When Sitting Bull was transferred to Standing Rock in 1883, after spending 20 months at Fort Randall as a virtual prisoner, McLaughlin quickly realized that he would need Gall and Grass as allies. The major took an instant dislike to Sitting Bull, who had claimed that he had received a letter from the President of the United States telling him that he would be the "big chief of the agency." When McLaughlin emphatically rejected Sitting Bull's claim of authority and proceeded to treat him just like any other Indian, the old chief became McLaughlin's major adversary. Sitting Bull assumed leadership of those more traditional Indians who opposed many of McLaughlin's policies.

It was at this point that McLaughlin began to organize a faction of friendly Indians at Standing Rock, headed by Gall and Grass. Even though Grass, who could speak English, was his most reliable ally, McLaughlin touted Gall's credentials the most.

Because Gall was a major participant at the Little Bighorn and during the Yellowstone expeditions of the early 1870s, he was regarded as a hero by many of his people. Grass, on the other hand, had a questionable war record against the U.S. Army, even though he had fought against his people's traditional Indian enemies. Gall also wore his prestige and authority with more tact and modesty than Grass. Sitting Bull's nephew, the respected warrior White Bull, resented the articulate Grass, insisting that he could "always say yes [to the government] but never no."

Sitting Bull's decidedly subordinate role in the politics at Standing Rock, however, would not be indefinite. The intervention of the Edmunds Commission would affect all of the agencies of the Great Sioux Reservation in one way or another. Newton Edmunds, a former governor of Dakota Territory, had been authorized by Congress in November of 1882 to visit the reservation, which remained massive even after the federal government had acquired the Black Hills in 1876 in retaliation for the Lakota role at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Edmunds Commission planned to divide the Great Sioux Reservation into six separate reservations—Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Lower Brulé, and Crow Creek. Most Lakota leaders liked the idea of each major tribe having exclusive ownership of its new reservation, uncomplicated by the old concept of common ownership by all Sioux people. Indeed, Gall and Grass, supported by McLaughlin, agreed to this reorganization on November 30, 1882, after the Edmunds Commission visited Standing Rock.

Not clearly articulated by the commission was its primary motive: it wanted to open up to white settlement those lands not allotted to individual Indians. Fortunately for the Lakota Sioux, the U.S. Senate, largely influenced by Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, refused to ratify the Edmunds agreement because it had been ratified by only a few chiefs and not by three-quarters of all adult Lakota males as required by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Senator Dawes, however, did believe in the partition of the Great Sioux Reservation and the opening of the reservation's unallotted acreage to white settlement. He pushed through Congress the Dawes General Allotment Act, which was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland on February 8, 1887. His new legislation called for the allotment of tribal reservation lands in which each head of the family would receive 160 acres, each single adult male, 80 acres, and each minor, 40 acres.

Cognizant of the problems caused by covetous white speculators, Dawes inserted a provision in his measure specifying that the title to each land allotment received by an Indian would be held by the government for 25 years. Most significant was Dawes's provision that those Indian lands not allotted could be opened up to white settlement. In fact, from 1887 to 1934, those unallotted lands, coupled with the land sold by Indians after the 25-year protection period had ended, reduced the total acreage for all Indians throughout the country from 138 million to 55 million.

In 1888 the Dawes Act was applied to the Great Sioux Reservation. Eager white landowners had been salivating over the prospect of acquiring lands not allotted to the Indians, which would amount to more than nine million acres. To obtain the necessary three-quarters approval from all adult Lakota males, a three-man commission was sent to the Great Sioux Reservation. It was headed by Capt. Richard H. Pratt, founder and superintendent of the respected Carlisle Indian Training School in Pennsylvania. The Pratt Commission decided to go to Standing Rock first, as most of the Indian leaders there had given their approval to the Edmunds plan.

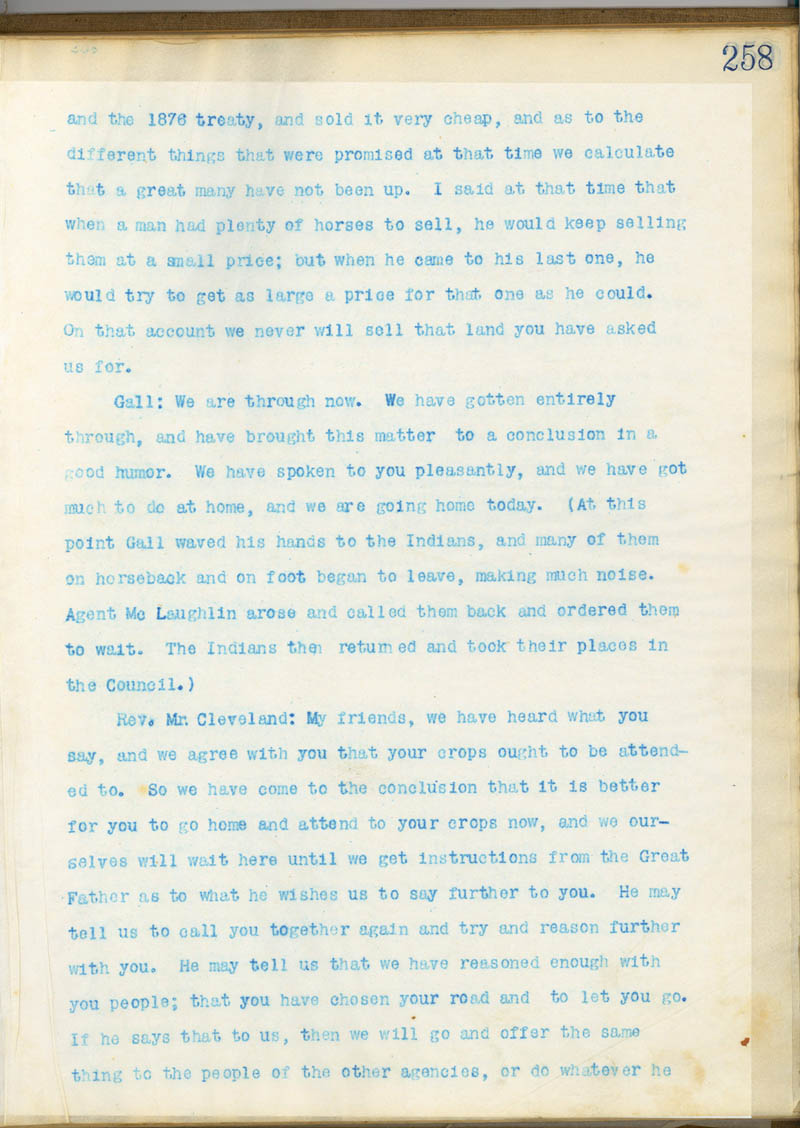

By this time, however, Gall, Grass, and other leaders of the more cooperative Indians were aware of the potential loss of land that would occur if they agreed to the 1888 Sioux bill, which embraced most of the provisions of the Dawes Act. Also opposed to the bill were Sitting Bull and even McLaughlin, who thought the bill was unfair. The Pratt Commission therefore encountered unexpected opposition to its efforts. Even though the overbearing Pratt kept pushing the Indians for more than a month in a series of prolonged hearings starting on July 23, the opposition could not be budged.

On August 21, in what became the last day of these futile hearings, Gall urged his compatriots to leave the meeting at once so they could return to their now neglected farms. "We have spoken to you pleasantly," he told the commission, "and we have got much to do at home, and we are going home today." McLaughlin did not support Gall in this open defiance. Instead he allowed one of the commission's members, the Reverend William J. Cleveland, a cousin of President Cleveland, to adjourn this final meeting in a face-saving way. The Pratt Commission did not fare well at the other agencies either and eventually concluded that the 1888 bill should be put into effect without achieving Indian consent.

A compromise was definitely needed to resolve this stalemate, and a trip to Washington by Sioux leaders seemed the best way to achieve it. As a result, a large delegation of Sioux leaders was assembled for the railroad journey to the capital. Most of the delegates, like Gall and Grass, were from the more cooperative factions. One curious aspect about Standing Rock's group was the inclusion of the intransigent Sitting Bull.

The Indian delegation was lodged in the upscale Belvedere Hotel and was given tours to such Washington landmarks as the Smithsonian Institute and the National Zoo. Much more important to the negotiators from each side was their meeting with Secretary of the Interior William F. Vilas. Vilas was supporting the 50 cents an acre payment for unallotted Indian lands specified in the Dawes Act, a provision that most of the Lakotas felt was grossly unfair, given that $1.25 an acre was the going rate for land in the public domain. During the discussion, which sometimes grew heated, Sitting Bull raised the ante to $1.25 an acre; 47 of the Indian delegates gladly supported him. Surprisingly, most federal negotiators were happy, too, because they saw Sitting Bull's proposal as an important breach in the ranks of the Sioux, which could result in some kind of compromise.

Secretary Vilas's staunch support for keeping the payment to Indians at 50 cents an acre for unallotted reservation lands became meaningless when the Republicans came to power in the 1888 November election. The strengthened GOP congressional delegation, supported by the newly elected President Benjamin Harrison, apparently wanted to partition the Great Sioux Reservation more than the Democrats had. Supporters of a new Sioux bill in 1889 agreed to pay the Sioux $1.25 an acre for all land homesteaded by whites during the first three years, 75 cents an acre for land sold during the next two years, and 50 cents an acre thereafter for all lands that remained unsold. New concessions, along with those made in the 1888 bill, were added to sweeten this controversial land acquisition.

A new commission was established, headed by George Crook, now a major general. The Crook Commission's charge was to convince three-quarters of all adult Lakota males from the six agencies to support the 1889 Sioux bill. Given the still-strong opposition to the Sioux bills at Standing Rock, this agency would be the last visited. The Crook Commission had 25,000 dollars to use for generous feasts, which it hoped would make the Lakota Sioux more receptive to the new bill's proposed compromises. Overall, this commission was much more effective than the Pratt Commission.

Prior to reaching Standing Rock, the Crook Commission won approval for this 1889 measure in every agency except for Pine Ridge, where Red Cloud and his allies were able to block the bill. When the commission convened its hearings at Standing Rock in July, leaders such as Gall, John Grass, Mad Bear, and Big Head were prepared to speak out against the second Sioux bill as they had for the first. There would, however, be one significant difference in 1889. Major McLaughlin had switched positions on this controversial issue, apparently believing that the Lakota Sioux could not get anything better from the federal government and might even do worse if they continued their resistance.

After three days of severe criticism of the 1889 Sioux bill by Standing Rock's Indian leaders, McLaughlin arranged a secret meeting with John Grass. He persuaded the more pliable Grass to use his oratorical skills to push for the new federal concessions included in the 1889 measure first and then make the difficult transition to support the new Sioux bill. After convincing Grass of the wisdom of this new strategy, McLaughlin asked him to persuade Gall to support this controversial switch in what had been an almost solid Indian position against these two Sioux bills.

Grass, who feared Gall's volatile temper, absolutely refused to lobby Gall in behalf of the bill. But the persuasive McLaughlin was able to convince Gall, who had become accustomed to following his agent's advice for the past seven years. Other Standing Rock Indian leaders followed suit.

Grass, "with the facility of a statesman," argued convincingly in behalf of the new position. Gall, Mad Bear, and Big Head gave shorter, but nonetheless influential, talks in behalf of the 1889 Sioux bill. These leaders compelled many undecided agency Indians to vote for the new bill, fearing to be left out if they did not.

According to McLaughlin, the plan was to have Grass be the first to give his approval to be followed by Mad Bear, Gall, and Big Head in that order. But Gall, fearing bodily harm by Sitting Bull and his enraged Hunkpapas, hesitated long enough for the Yanktonai Sioux chief Big Head to step in and win the "coveted distinction" of being the third signer. Instead, in the official roster of those Indians affixing their mark to the bill, the reluctant Gall was number 416 of 803 signers. The result was a humiliation for Gall, as more was expected of him, and a bitter disappointment for Sitting Bull, who said after the vote: "There are no Indians left but me."

The ratification by these confused Sioux reservation Indians was followed by a number of disappointments, if not tragedies, for them. Congress failed to deliver on some of the promises made to the Sioux during the ratification process, and President Benjamin Harrison, on February 10, 1890, accepted the new agreement reached in the Sioux Act of 1889 even before the necessary land surveys were made.

Congress also failed to revoke an unpopular $100,000 cut in the beef allowance, which had been made prior to the ratification fight but had nothing to do with the negotiations over the new Sioux Act. The growing resentment of Lakotas living on the six new reservations created by this controversial new law was compounded by the severe winter of 1889–1890, which was followed by a hot and dry summer that caused serious crop failures. The subsequent decline in agricultural production, accompanied by the cut in beef allowances, drove some Lakota families toward starvation. Sicknesses often associated with food shortages, such as influenza, measles, and whooping cough, even caused death in a number of cases. This economic downturn, which affected white farmers as well as Native American ones, slowed land sales sanctioned by the Sioux Act during that three-year period when the Sioux by law were to be paid $1.25 per acre for their ceded lands.

Most of these setbacks occurred during a disturbing new Native American movement, which terrified many white farmers living near the six new reservations. It was called the Ghost Dance, and it was sparked by a Paiute shaman from Nevada named Wavoka. He had a vision in which the regenerated ancestors of the Indians would return to life, along with the vanishing buffalo, while whites would be pushed back to their original homes across the ocean. To hasten the process, Wavoka stressed the frequent performance of a mournful circle dance, which many settlers called the Ghost Dance. The new Ghost Dance religion attracted many of the now disillusioned Lakotas, a number of whom lived in the newly created Pine Ridge Reservation. The Ghost Dance was not a war dance, but many whites characterized it as such.

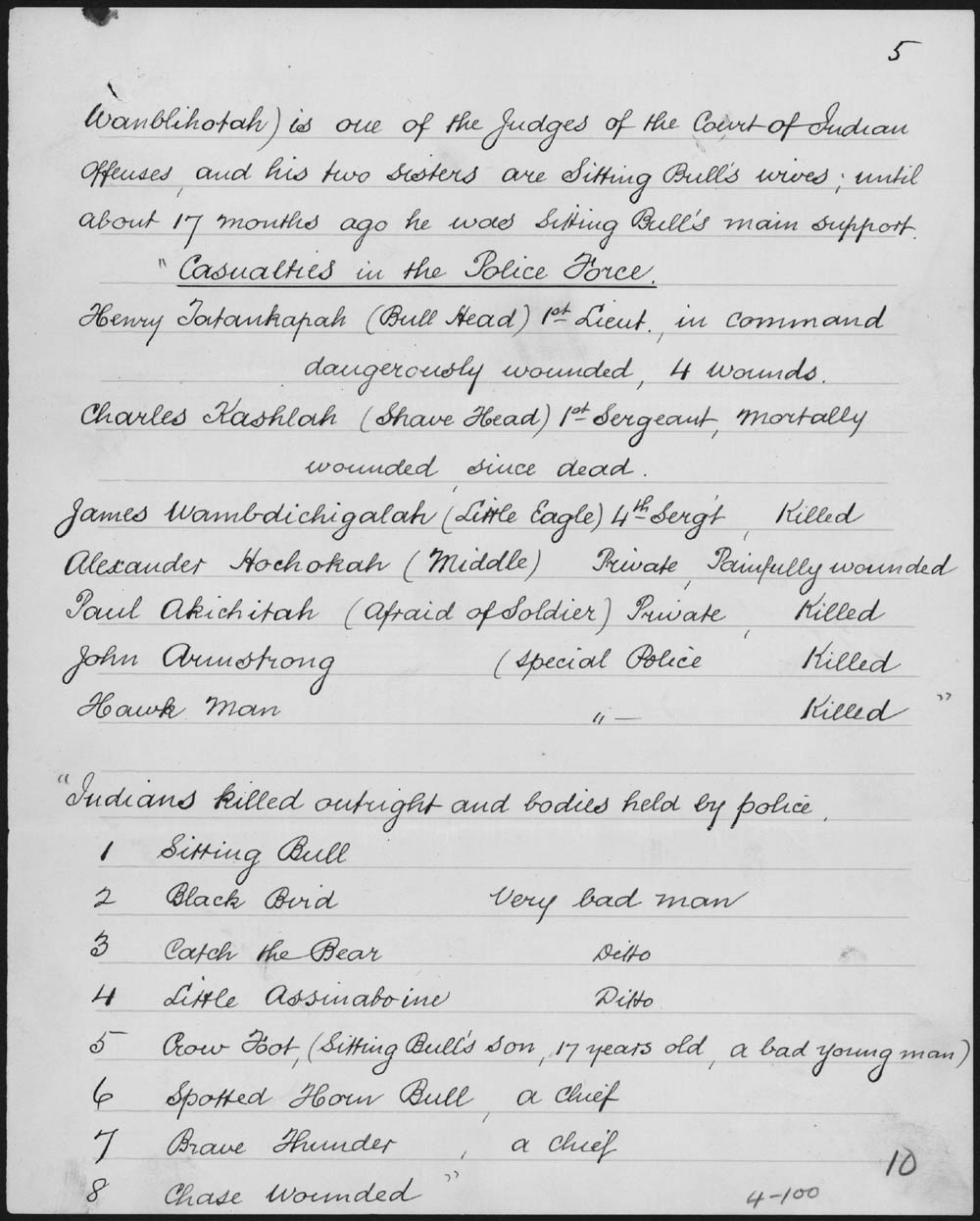

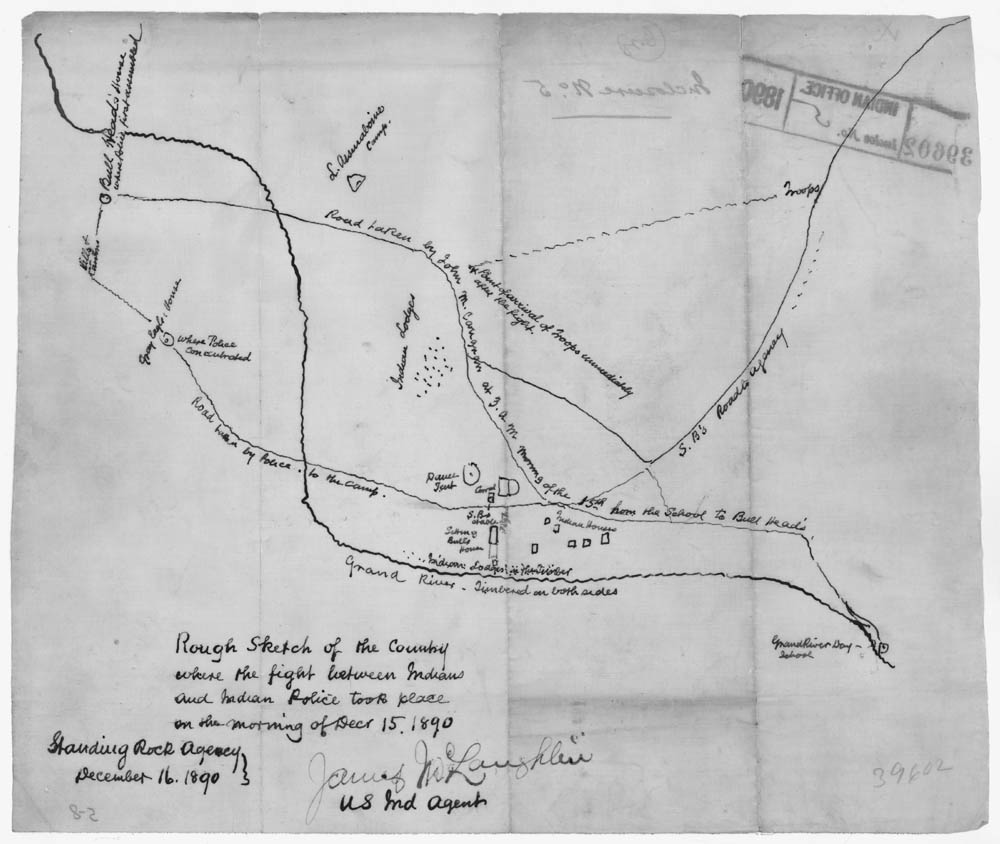

When Sitting Bull agreed to leave Standing Rock with many of his Hunkpapa followers to visit Pine Ridge in order to understand better the nature and purpose of the Ghost Dance, panic occurred at Standing Rock, with Gall and Grass asking McLaughlin for weapons so they and their people could defend themselves against the Ghost Dancers. Sitting Bull's death while being arrested by Indian police under McLaughlin on December 15, 1890, profoundly worsened the crisis. Many of the old chief's followers accompanied Big Foot and his Miniconjou band members to Pine Ridge, where troopers from the Seventh Cavalry fired upon them in a bloody and unplanned encounter at Wounded Knee Creek on December 29, 1890.

During the difficult months following the acceptance of the 1889 Sioux bill, Gall no doubt felt frustrated. The factionalism at Standing Rock had never been more evident, and Gall's role in reservation politics had never been more controversial. There is evidence that he was deeply disturbed by the death of his old friend and ally Sitting Bull; he even questioned McLaughlin's Sioux wife about the circumstances surrounding Sitting Bull's tragic demise but received little in the way of reassurances from her. He did not break with Major McLaughlin, however, but did become less involved in the divisive politics that continued to rage at Standing Rock.

One reason for Gall's relative lack of participation in reservation affairs during the early 1890s was his declining health. The more sedentary lifestyle at Standing Rock was not conducive to the once highly active Gall, who grew increasingly obese, despite his conscientious work in farming his own plot of ground and rendering services to others as a district farmer. Although church records claim he died of heart failure on December 5, 1894, the testimony of a friend, photographer David F. Barry, that he died because he drank too much of an apparently lethal or unsafe antifat medicine still circulates among historians of the Lakota Sioux.

One notable aspect of Gall's 14 years as a reservation Indian was his ease in assimilating into the white culture after he reached Standing Rock. One prominent scholar, Duane Champagne, characterized Gall as one of the most Europeanized Indians he had ever studied. If Gall did, indeed, die from an overdose of an antifat medicine, it was probably because of his growing faith in the advanced technology of white culture; if one dose would not do it, then a larger one certainly would.

He believed that education was the essential way for an Indian to advance in the dominant white culture. He let his daughters be educated by the Episcopal clergy at St. Elizabeth's mission, to which he later donated what he could to guarantee the mission's success. His baptism in the church did not occur until July 4, 1892, because, like most Indians, he still embraced much of the religious faith of his people. He made his final commitment to Christianity on November 12, 1894, by a church marriage to his fourth wife, Martina Blue Earth, three weeks before his death in December.

Although Gall lived a controversial life following the Great Sioux War, his commitment to this new way of life was an honest one. His sincerity was demonstrated by his wholehearted participation as one of Standing Rock's district farmers and as a judge on the Court of Indian Offenses, where, as a culture broker, he would thoughtfully interpret the law with the welfare of his people in mind as he did it.

Robert W. Larson is a professor emeritus of history at the University of Northern Colorado. He received his bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Denver in 1950 and 1953 and his doctorate from the University of New Mexico in 1961. He has written several books on western history, including Red Cloud: Warrior-Statesman of the Lakota Sioux in 1997 and, in 2007, Gall: Lakota War Chief, which received the Spur Award for the Best Western Nonfiction Biography for 2007 from the Western Writers of America.

Note on Sources

Archival records utilized in this study for Gall's surrender include Sioux Campaigns. . . , 1879–1881, Special Files, Military Division of Missouri, Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, Record Group (RG) 393, "Special Files" of Headquarters, Division of the Missouri, Relating to Military Operations and Administration, 1863–1885 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1495, roll 5). Correspondence from these special military files is also located in the Major James McLaughlin Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers, 1855–1937, State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck. Also relevant are the Fort Buford Returns, June 1866 to September 1895, in Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94, Returns from Military Posts, 1800–1916 (M617, rolls 158–159. Gall's controversial approval at Fort Rice of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie is found in the "Council of the Indian Peace Commission with Various Bands of Sioux Indians at Fort Rice, Dakt. T., July 2, 1868" in Papers Relating to Talks and Councils Held with Indians . . . in Years 1866–1869, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1910.

For Gall's involvement in the affairs at Standing Rock, see Appointment Approval Letters, Standing Rock Correspondence from 1865, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75, NARA–Central Plains Region, Kansas City. Also at the Kansas City regional archives are the Minutes of Sioux Commission of 1888 [handwritten ledger], Standing Rock Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75. The struggle over the controversial Sioux bills of 1888 and 1889, which were first dealt with by the 1888 Sioux Commission, are also chronicled in the relevant House and Senate documents for these years. Information regarding Sitting Bull's arrest and death at Standing Rock is found in Report by James McLaughlin . . . on the Death of Sioux Chief Sitting Bull, December 15, 1890, Special Case 188, RG 75, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. For the vital statistics of Gall's death at Standing Rock, as well as his Episcopal baptism and marriage records, consult Standing Rock Mission Records, Vol. A-1, Augustana Collections, Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Manuscript collections consulted for the article are the D. F. Barry Papers, State Historical Society of North Dakota; Walter S. Campbell Collection, University of Oklahoma Library, Norman; Doane Robinson Papers, South Dakota Historical Society, Pierre; and Josephine Waggoner Papers, Museum of the Fur Trade, Chadron, Nebraska. Other primary sources utilized include newspapers, such as the Bismarck Tribune, the Daily Argus (Fargo), and the Fargo Forum, which are located in the Frontier Newspaper Collection, Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library, or at the North Dakota state archives. One published primary account essential to this study was James McLaughlin, My Friend the Indian (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1910). Another was Stanley Vestal (pseudonym for Walter S. Campbell), New Sources of Indian History, 1850–1891 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1934), which reproduces some important correspondence regarding Gall's life at Standing Rock.

Secondary accounts employed in this study include Carole Barrett, Major McLaughlin's March of Civilization (North Dakota Humanities Council, 1989); Raymond J. DeMallie, "Teton Dakota Kinship and Social Organization," University of Chicago Ph.D. dissertation (1971); James R. Frank, "Chief Gall and Chief John Grass: Cultural Mediators or Sellouts?" University of Montana master's thesis (2001); Jerome A. Greene, Yellowstone Command: Colonel Nelson A. Miles and the Great Sioux War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991); Robert W. Larson, Gall: Lakota War Chief (Norman: 2007); Louis Pfaller, James McLaughlin: The Man with an Indian Heart (New York: Vantage Press, 1978); Margaret Connell Szasz, ed., Between Indian and White Worlds: The Culture Brokers (Norman: 1994); Robert M. Utley, The Last Days of the Sioux Nation (Yale University Press, 1963) and The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull (Henry Holt, 1993); and Wilcomb E. Washburn, The Assault on Indian Tribalism: The General Allotment Law (Dawes Act), ed. Harold M. Hyman (Lippincott, 1975).