“No Little Historic Value”

The Records of Department of State Posts in Revolutionary Russia

Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1

By David A. Langbart

Department relies on your judgment as to leaving your post and taking measures requisite to safeguard staff and archives from falling into enemy hands. Seals, codes, cipher messages or translations should be taken with you or if this impossible should be burned and seals destroyed.

—Department of State telegram to U.S. Ambassador in Petrograd, February 25, 1918

Search archives your mission for any records or archives of former American Embassy in Russia or of American Consulates formerly situated in territory now part of Soviet Union. . . . Such records . . . should be carefully packed and forwarded under seal to Department by nearest available pouch service.

—Department of State telegram, December 2, 1933

The study of American foreign relations in the 19th and early 20th centuries depends largely upon the files of the Department of State and the records of American diplomatic and consular posts. While the department's central files remain indispensable for this research, the post files have their special value. They provide a better sense of what went on in a country than do the central files and often include documents not found in the central files, particularly communications within and between posts.1

The files maintained at overseas posts, however, have suffered significant loss and damage over the years. The vagaries of both nature (fire, earthquake, volcano, hurricane, vermin) and man (war, revolution) have all taken their toll.2 This is particularly true of posts in Russia. These losses have limited scholars of U.S.-Russian relations in their ability to fully understand and explain what occurred in the years leading up to the revolutions of 1917 and the subsequent Bolshevik consolidation of power.

As the United States withdrew its diplomatic and consular representation from Russia during the five years after the Bolshevik seizure of power in November 1917, Department of State personnel destroyed or abandoned some records and evacuated other files to posts in surrounding countries. Over the next two decades, the department took action to locate or account for the files. This is the story of what happened to those records.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917, the United States did not immediately break relations. Instead, Americans continued their work in a fruitless effort to maintain Russian participation in the war against Germany and to gather information on the changes overtaking Russia. Not until 1918 and 1919 did the United States begin to close its posts in response to Bolshevik actions. The last offices, the consulates in Chita and Vladivostok in Siberia, did not close until 1923, when those cities also came under Bolshevik control.

Some posts closed in early 1918 because of German military action. When negotiations between the Germans and the Russians at Brest-Litovsk broke down in February 1918, the Germans renewed their assault on Russia. By that time, the Russian army had ceased to function as an effective fighting force, and the Germans advanced rapidly, threatening Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities where the United States had offices.

On February 27, 1918, Ambassador David R. Francis closed the embassy in Petrograd and moved it east to Vologda to avoid the approaching Germans.3 Since he expected a quick return to Petrograd, Francis directed staff to take only records needed for current business. The staff burned the previous 10-year accumulation of sensitive files and left the remaining records in the care of the neutral Norwegians, who assumed responsibility for American interests in Petrograd.4 One vice consul remained in the city to gather information and to take care of consular business.

In July the Bolsheviks pressured the nine diplomatic missions in Vologda to move to Moscow, which they considered safer. The missions, including the Americans, instead chose to relocate north to Archangel, where they arrived on July 26.5 The Americans took all of their files in Vologda to Archangel.

When the U.S. embassy in Russia closed in September 1919, the staff deposited most of the records it had brought from Petrograd, along with those created in Vologda and Archangel, in the embassy in London. Some files ended up at the American consulate in Vladivostok, too, taken there by staff forced to evacuate to the east. The records earlier left behind in Petrograd were abandoned.6

As the Germans moved closer to Moscow in February 1918, the staff of the American consulate general prepared to evacuate. Consul General Maddin Summers ordered the destruction of the most sensitive files.7 He sent most of the recent records east, to Samara, in the care of Vice Consul Orsen Nielsen, who stored them there in the safes of the International Harvester Company office. The older records remained in Moscow. When the consulate general closed in August 1918, the staff took some of the remaining records to Stockholm, while others came to rest in Vladivostok.8 The remainder of the files remained in Moscow in the care of the Swedes and the Norwegians.

Other offices in European Russia faced different problems. The posts at Batum and Tiflis in the Caucasus closed in May 1918, when the Germans overran those cities. They reopened in early 1919, only to close for good when the Bolsheviks captured the cities in 1921. The remaining offices in European Russia—Kiev, Odessa, Murmansk, Archangel, and Rostov-on-Don—shut down as Bolshevik control spread.

As the posts closed, staff either destroyed their records, placed them in the care of a neutral power, or moved them to an American post in a nearby country. As the consular officer in Kiev reported, he "deemed it advisable to get rid of any papers that might be of interest to the Communist regime."9 Additional confusion resulted from the temporary offices established in places such as Novgorod and Tashkent during the few months that some American consular personnel remained in areas under Bolshevik control. Those offices generally kept few records and destroyed them when they closed.10

Even as events continued to unfold, the Department of State showed interest in the embassy's files. In June 1919, in conjunction with its inquiry into the authenticity of the so-called "Sisson Documents," which purported to prove a German-Bolshevik conspiracy to take Russia out of the war, the department requested the embassy, then located in Archangel, to furnish all documents that contained "signatures of the various Commissars." Felix Cole, the chargé d'affaires ad interim, removed 22 documents from embassy files and sent them to Washington.11

Later in the year, after the embassy closed, the Division of Russian Affairs sought to consolidate the records of various posts in Russia in an effort to make the department's files complete.12 At the same time, the department's Bureau of Accounts was trying, ultimately unsuccessfully, to settle embassy accounts.

The department therefore ordered the files of the embassy at all its various locations and of the consulate at Archangel shipped to Washington.13 The account files went to the Bureau of Accounts, but they proved to be of little help. The correspondence files went to the Russian Division, where Arthur Bullard used them as he worked on a "white paper" on American policy in Russia during the first six months of 1918. The department also reviewed the post files to ensure that its central files contained an accurate and comprehensive collection of communications with the embassy in Russia.14

The files transferred to Washington continued to see use during the 1920s as former staff members and relief personnel made claims for service in Russia. In addition, the owner of the embassy building in Petrograd made claims for rent. Several times the department informed interested parties that it was "almost impossible" to liquidate accounts because of the inability to locate the necessary vouchers and account books or that information could not be confirmed "without reference to some records" but that "no access can be had . . . to any of these archives."15 In several instances, the department communicated with former embassy employees to try to obtain the information necessary to settle some of the claims.16

The conditions at the posts in Asian Russia differed markedly from those in European Russia. While the situation there from the time of the November Revolution to the Bolshevik consolidation of power was more fluid, American withdrawal was more orderly. Consul General Ernest L. Harris held jurisdiction over the posts at Irkutsk, Omsk, Tomsk, Novonikolaevsk, Ekaterinburg, Cheliabinsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Chita. As the Bolsheviks overran those cities, American officials pulled out, depositing their files with the consul general, who operated out of a special train. Harris noted that its use "was rendered necessary by the near proximity of the Bolsheviks. Preparedness for immediate evacuation was the order of the day."17

In February 1920, the United States closed the remaining posts in Siberia except the consulates at Chita and at Vladivostok. Harris, who returned to the United States, placed all official records and files in his custody with the consulate at Vladivostok. These included some files from the embassy in Petrograd and the consular offices in Moscow and Samara that had been evacuated to the east.

The department soon began directing inquiries to Vladivostok that could be answered only from the files of the various posts in Siberia now gathered there. The staff found it difficult to respond because the records had "been thrown pell mell into canvas bags."18 To remedy the situation, the department instructed Consul David B. Macgowan to have the files arranged and bound, a job that neared completion by January 1923.19 At the same time, the standing of the U.S. consulates in Chita and Vladivostok became precarious when the Soviets took over in those cities.

Now headed by Consul S. Pinkney Tuck, those posts received orders in March to send all records and archives to a safe location if evacuation became necessary.20 Apparently the department had learned from its mistakes during the closing of the European posts and had determined to give precise instructions on what should be done with records when closing the last two offices in Russia.

When the consulates closed in early spring 1923, Tuck was unable to fully carry out the orders relating to records. When he reported plans to leave some files behind in storage, the department directed that he give special attention to evacuating the files beginning January 1, 1918, including those from the defunct offices in Siberia.21

Ultimately, Tuck sent the files from Chita, the records of the Inter-Allied Railway Committee, and the more sensitive files from Vladivostok to the U.S. consulate in Harbin, Manchuria, for transshipment to Tokyo.22 Tuck took other files, including those from the defunct offices in Siberia, directly to Tokyo but left records relating to war prisoner relief and the consulate's files from 1898 through 1917 in storage in Vladivostok.

On May 19, the embassy in Japan reported to Washington that Tuck had arrived.23 On September 1, 1923, a devastating earthquake struck Tokyo. The resulting fire that swept the city destroyed the embassy and with it, the records brought out of Russia. In the aftermath, Tuck reported: "Owing to recent events in Japan I am afraid that it is more than likely that all archives may have been lost."24 Because the office in Harbin had yet to ship the files it held, those records survived.

At the same time that Tuck was evacuating Vladivostok, the Department of State learned of the recovery of some files. In 1921, the United States established the American Relief Administration (ARA) to assist European countries, including Soviet Russia, in famine relief. During May 1923, John A. Lehrs, chief of the Liaison Division of the Russian Unit of ARA, visited the building formerly occupied by the American consulate general in Moscow. While there, the proprietress showed Lehrs a locked safe and several cases of records left behind in 1918.25 These were prisoner relief files from the embassy in Petrograd for the years 1914 through 1917 and the records of the consulate general in Moscow for the period 1857 through 1918.26 The ARA arranged to ship the records to Riga, Latvia, where the embassy files ended up in the American legation and the consular files in the American consulate.27

In May 1925, in a further effort to locate records, the Department of State wrote to the International Harvester Company about the records of the Moscow consulate general that had been sent for storage in the company's Samara office in 1918.28 The company reported that records had indeed been stored in one of its storerooms in Samara, but only temporarily, and when a consular office opened in the city in the spring of 1918, the files were returned to government custody. Beyond that, the company had no further information.29

The department pressed on and contacted several Foreign Service officers who had served in Samara. Among them was George W. Williams, who had been the consul in charge when the office closed.30 Williams, now employed by the Iowa Loan and Trust Company Bank in Des Moines, reported in May 1926 that he had taken all the files from Samara to Omsk, where he turned them over to Consul General Harris. Furthermore, he understood that Harris had deposited all the records in his possession with the consulate at Vladivostok when he left Siberia.31

In December 1925, additional information about post records reached the department when the Persian government informed American officials that their consulate in Tiflis held some records from the American consulate in that city.32 The Division of Eastern European Affairs, headed by Robert F. Kelley and responsible for American policy toward the USSR, decided that "from a political point of view" it was impossible to send an American to claim the records. Kelley, therefore, recommended that the Persians forward the files to either Teheran or Constantinople, but that "examination of these papers by Soviet customs officials should be avoided."33 The department made that request, but the Persians were unable to arrange for transfer of the files.34

Additional positive news arrived in January 1926, when the American embassy in Tokyo sent to Washington some records from the embassy in Petrograd and from the consulate general in Moscow. The staff had found them in the vault used by the embassy to store confidential materials after the earthquake of 1923. Ambassador Charles MacVeagh characterized the files as having "no little historic value," but since the embassy did not have the proper means for caring for the files, he ordered them sent to Washington.35 Later in the year, the embassy shipped records from the consulate at Vladivostok that the staff found in another vault. Those files turned out to be the records that had been sent to Harbin first, and so did not arrive in Tokyo until after the earthquake.36

During late 1928 and early 1929, the department faced two claims cases that required information from the files of posts in Russia. In both cases, the department had to inform the claimant of the unavailability of pertinent records.37 This led Kelley and Earl L. Packer of the Division of Eastern European Affairs to initiate what became the department's most concerted and all-encompassing effort to locate records of its former offices in Russia.

Concerned that the department was unable to adequately represent U.S. citizens and protect national rights and interests, in May 1929, Kelley sent a memorandum, prepared by Packer, to Herbert Hengstler, chief of the Division of Foreign Service Administration, that suggested "that a careful search of the Department's records be made with a view to ascertaining in so far as possible where the archives . . . are now located, and that the result . . . be embodied in a detailed memorandum."38 Kelley was particularly concerned that "in view of the conditions in Russia and the lapse of time since the records were last under responsible control, they may never be recovered."39 Hengstler agreed with the recommendation and also suggested that all surviving files be gathered in Washington.

To secure information, the department asked 13 Foreign Service officers who had been in Russia at the time the various offices closed what they knew about the posts' files.40 Before the instruction was sent, Kelley was asked to provide comments, both because it involved his division's area of responsibility and because he had helped initiate the effort. His recommendation for changes is indicative of the U.S. attitude toward the USSR at the time. September and October 1929 saw the renewal of "recognize Russia" agitation in the United States, and Kelley, in order to squelch rumors before they started, added this disclaimer:41

It may be added for your information that this instruction does not imply that any change is contemplated in the policy of this Government with respect to the present regime in Russia.42

The department sent the instructions in October 1929.43 Responses arrived over the next four months. Beyond providing interesting narratives of their experiences, the reports added little to the information about post records already available in the department's files.44

At about the same time that the department was sending out the request for information, it received unsolicited information about the records left in storage in Vladivostok when the consulate there closed in 1923. In late October 1928, the American consul in Harbin, George Hanson, reported that he had received information that in July Soviet authorities had broken into the storerooms holding the records and property left in Vladivostok and seized everything. Since the information he had received was not definitive and the United States had no official dealings with the USSR, Hanson suggested that he write to the German consul in Vladivostok requesting that his counterpart investigate and, if possible, take charge of the property. In December he was told to proceed but to not mention the department's authorization.45

Coincidentally, shortly after sending that instruction, the department received a despatch from Edwin Neville, the chargé d'affaires ad interim in Japan, reporting that on December 19, the Soviet ambassador had approached him at a diplomatic luncheon given by the Japanese minister for foreign affairs and asked about the disposition of property from the U.S. consulate in Vladivostok. Neville reported that he told the Soviet ambassador that he had neither knowledge nor authority to discuss the matter and requested guidance from the department before taking any action.46 The department acknowledged Neville's report but deliberately provided him with no instructions for further action. As one official noted, "We do not deal with the Russians just now. Eventually I assume we will want to hold some one accountable for this seizure—but don't see that we are in a position now to do so."47

In April 1929 Consul Hanson in Harbin reported requesting that the German consul in Harbin, Doctor G. Stobbe, contact the German consul in Vladivostok. Stobbe had to write several times before receiving a response in late March that confirmed that the archives and other property in storage had been seized. The German consul could not, however, pinpoint the date on which that had occurred, nor could he shed any light on what had subsequently happened to the archives and other property, since he did not deem it practical to make a direct inquiry on the matter. Hanson concluded that the German consul was afraid to get involved but noted the presence of the Japanese consul in Vladivostok and Soviet officials connected with the Chinese Eastern Railway as possible channels through which inquiry could be made. Given the liabilities of either approach, Hanson indicated that he would take no action without instructions.48 When asked for guidance in preparing instructions, the Division of Eastern European Affairs concluded that it was inadvisable to work though either of the channels mentioned, and since the consul would not take action without instructions, the department filed the report without any response.49

The department took no further substantive action on the records issue until early 1932, when Kelley pressed for completion of the study that he had recommended in May 1929. One reason he had asked for a report was that he believed that the number of claims cases for which the records would be useful was certain to increase.

In May 1932, Leslie Mayer of the Division of Foreign Service Administration completed a report titled "Archives of Former Offices in Russia." Mayer, who based his study on information he found in the department's files, noted that the report was "unfortunately, neither complete nor definitive," and he "doubted it can ever be satisfactorily completed." While the report covers most of the posts in Russia, it is just an overview, and Mayer, for reasons that are not clear, missed some of the information available in the department's files. Most notably, he did not mention the more recent developments relating to the records left behind in Vladivostok. The bulk of the report is a list of the posts and offices in Russia with a brief statement of the fate of the records from each. Mayer concluded that by 1932, the traceable archives had reached eight scattered locations: Istanbul, Tokyo, Riga, Oslo, London, the Department of State, and possibly Tashkent and Amsterdam.

While Kelley thought the files useful, Mayer concluded that given time and conditions, the records actually were of little use to the department. Nevertheless, he suggested that the offices believed to have the records be ordered to forward the files to Washington.50

In September 1932, the Division of Foreign Service Administration contemplated sending a circular to all Foreign Service officers in order to ensure that any offices having records and all personnel having knowledge of the matter would be contacted.51 Nothing was done until the following year.

In December 1933, a month after the United States and the USSR had established diplomatic relations, the department sent a circular telegram targeted at those posts most likely to have files from the Russian posts: the legation and consulates in China, the embassies in Japan and England, the consulate at Istanbul, the legation in Latvia, and all other European offices. The department ordered those posts to search for any records of posts "formerly situated in territory now part of the Soviet Union" and to send any that were located to Washington.52

Despite the passage of time, the responses actually provided the department with new information. The embassy in London reported that it had the records of the embassy and consulate at Archangel that had been stored there when Archangel was evacuated in 1919.53 The consulate at Istanbul found files from the consulates at Batum, Odessa, and Tiflis.54 The consulate at Oslo had records from the consulate at Murmansk.55 The legation in Latvia reported finding records from the embassy in Petrograd.56 And the consulate at Harbin located files from the consulate at Chita.57 As ordered, those posts sent the records to Washington. Posts in other cities sent negative reports, and some did not reply at all.

The legation in Persia reminded the department that the Persian consulate in Tiflis still held files of the former American consulate in that city.58 Robert Kelley feared that any attempt to recover the records might upset the newly established U.S.-Soviet relationship. He therefore recommended that the situation be investigated, and, if no complications arose, that the records be sent to the American embassy in Moscow for shipment to Washington.59

In early March 1934, George Wadsworth of the legation staff stopped in Tiflis en route to Bucharest from Teheran. Wadsworth learned that the Persians had earlier attempted to move the files, but Soviet officials refused permission because the United States and the USSR had not established diplomatic relations. Since that was no longer true, the Persians anticipated no difficulties. Wadsworth's examination indicated that the crates in the custody of the Persians contained the archives for Batum for the period from 1886 to 1914 and for Tiflis for 1916.60 As expected, Soviets officials presented no obstacles, and in May the department ordered the embassy in Moscow to take custody of the records and send them to Washington.61

Further impetus for gathering records of Russian posts came from the department's larger project to bring records of all Foreign Service posts antedating 1912 to Washington. The project, a combined safety and economy measure, had begun in 1932. The date span included most of the records from the Russian posts. Those files that did not fall into the relevant time period came from offices no longer in operation, and clearly, records from pre-revolutionary Russia had little use in the Soviet Union. As a result, in May 1934, when the newly opened consulate in Moscow suggested that the old Moscow records be sent there, the department responded with a sharply negative answer.62

There also remained the issue of the Vladivostok consulate records. In 1929 the department allowed that issue to drop. As late as January 1932, all the department knew was that Soviet officials had opened the two rooms in which the records and other property were stored and removed the contents. It had no definite information on the fate of the records and property.63

In November 1931, Consul Hanson in Harbin reported to the embassy in Peking on recent contacts with his German counterpart. The Germans had been asked by Soviet officials to ascertain if and how the United States intended to remove the unspecified American property held by the Soviets.64 The department ordered the sale of all furniture and furnishings and the shipment of records and archives to Harbin. Ultimately, some typewriters were shipped to Harbin and sold there, and the other office equipment and furnishings were sold in Vladivostok, but no records were found, and Soviet officials provided no information about their fate.65 What exactly happened to those records remains unknown.

The search for archives of former Russian offices received a great boost in 1934, when the department recovered the records of the embassy in Petrograd. That feat was the work of one man, Angus Ward, one of the first Americans stationed at the new American embassy in Moscow. While serving as a Foreign Service officer at the consulate in Mukden, China, in 1926, Ward heard rumors about the property of the former embassy. When he received assignment to the Soviet Union, he decided to investigate, despite earlier reports that the files had been destroyed.66

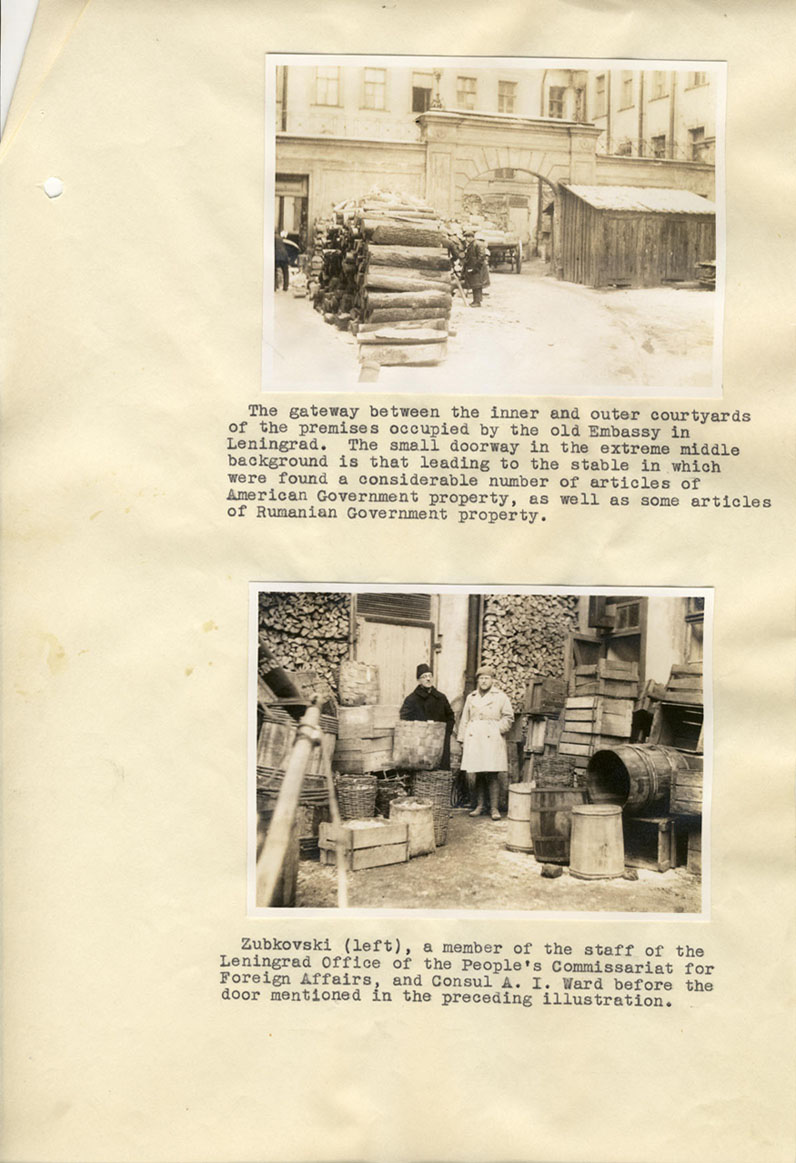

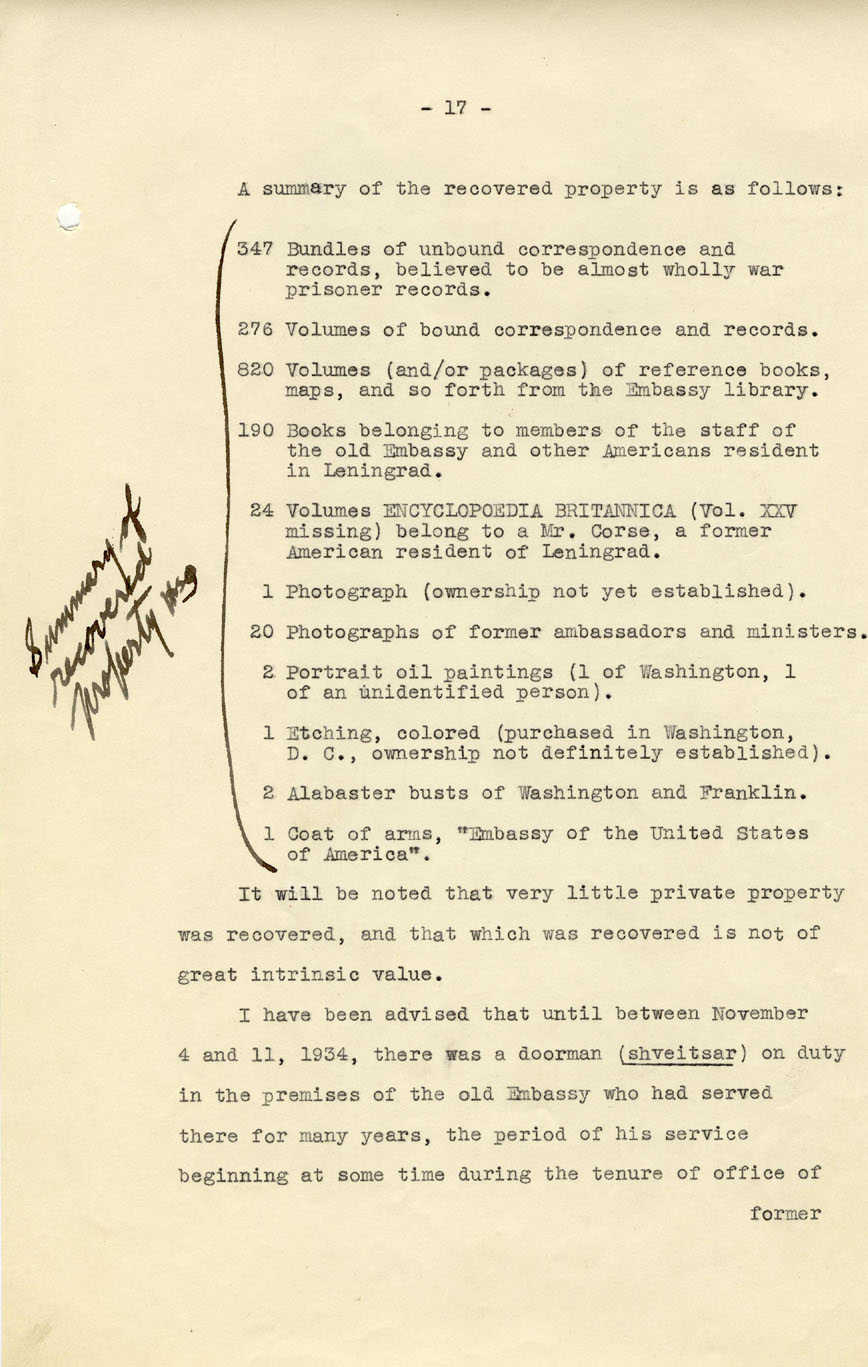

On July 4, 1934, Ward made the first of several trips to Leningrad (formerly St. Petersburg/Petrograd). During a visit on November 4, he called on Grigori Weinstein, the Leningrad agent of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, and requested permission to visit the old embassy building. Weinstein rebuffed him with the assurance that a search had been made previously and that nothing had been found because all the records had disappeared during the revolutionary period.67 As Weinstein said, "It is useless to go there Mr. Ward. Seventeen years! Revolutionary days, you know what happens in time of revolution."

Ward, however, knew better. He had information from three sources in Leningrad that the archives still existed. He persisted in his desire to visit the old building and informed Weinstein that he would return a week later.

On November 11, Weinstein reluctantly informed Ward that arrangements had been made to visit the building, now headquarters of the Soviet company ROSAT, that same day. Inspection of the building revealed some furnishings similar to those of the former embassy, but since they bore no markings, Ward did not press the issue of ownership. Weinstein's assistant, Mr. Orlov-Ermak, led the tour and hurried through the east wing of the building. That displeased Ward because his informants had told him that the old records were on the third floor of that wing. Under the guise of examining a mirror, he reached the stairs to the third floor and later reported:

I walked up the stairway, practically dragging Orlov-Ermak who was assuring me volubly that there was nothing on the third floor but an office similar to [those] . . . we had just visited.

Ward instead found a room lined with cupboards all sealed with wax impressions of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs. The lower cupboards had wooden doors, but those on top had glass doors. Scanning them, he saw a volume of the series Foreign Relations of the United States, published by the Department of State. Ward convinced the reluctant Weinstein and Orlov-Ermak to open additional cupboards, where he found many U.S. government publications. All of the books contained the bookplate of the United States embassy. Ward then asked to see the contents of the cupboards with wooden doors. Orlov-Ermak assured him that they contained only ROSAT files but still opened one when Ward insisted. Inside they found bound and unbound files of the former embassy. A search of one of the carriage houses in the courtyard revealed the embassy coat-of-arms above harness hooks and a large pile of volumes that proved to be the embassy's archives dating back to 1807.

Ward notified the department of his discovery when he returned to Moscow. He received instructions to return to Leningrad to supervise the examination, collection, and transfer of the recovered records to Moscow. In March and May 1935, the embassy shipped those archives to Washington, where they were placed with the other records of Russian posts.

In October 1935, the department sent a followup to its circular message of December 1933, to offices that had failed to respond to the earlier inquiry.68 This time, all posts reported finding no records. With that circular, the Department of State's formal search for the archives of its former posts in Russia ended.

Overall, the effort led to the discovery of some previously unknown records and the centralization of all existing files in the department. In February 1938, all surviving materials from the embassy and consular offices in Russia in the custody of the Department of State were transferred to the National Archives.69

The fate of the records of the American posts in Russia figured prominently in a September 1936 memorandum for Secretary of State Cordell Hull prepared by Green H. Hackworth, the Department of State legal adviser. Hackworth's report dealt with the precedents for evacuating, at government expense, Americans in countries torn by civil strife or war and with previous practice in closing diplomatic and consular posts is such areas, "particularly as to the disposition made of official records."

Based on the examples of events in seven countries, including Russia, Hackworth concluded that the department's practice in protecting overseas property, including records, had not been uniform and that "instructions have not been as specific as might be desirable." He therefore recommended that uniform instructions be sent to all posts and be supplemented as needed.70 Despite this recommendation, the department did not take serious steps to improve the handling of archives and records in emergency situations until after World War II.

The story of the records of American posts in Revolutionary Russia continued late into the 20th century. In October 1990, archival officials of the Soviet Union turned over to the United States several files from the U.S. consulate in St. Petersburg/Petrograd. The records, dating primarily from 1917 and 1918, were among those abandoned by American officials when they left the city in 1918 and were subsequently seized and preserved in the Soviet Archives.71 Given the preservation of the Petrograd files, perhaps the records of the Vladivostok consulate yet survive.

The loss and scattering of files of the European posts can be attributed to optimism, lack of procedural guidelines, and confusion. American officials expected to return to their offices soon. Instead of hauling around large volumes of files dating back to the 19th century, they decided to leave them behind in the care of neutral governments. Officials took to their new locations only sensitive files and records of a recent date necessary for current business. The Department of State had no procedures for posts to follow in such emergency situations, and except to inform the embassy and consulates that they should take "measures requisite to safeguard staff and archives from falling into enemy hands," it gave none.72 If security could not be guaranteed, they destroyed the sensitive records.

Americans in European Russia faced a confusing and unstable situation. To prevent the possibility of records falling into either German or Bolshevik hands, the staffs generally took what they considered requisite measures—destruction, a measure that later caused problems for the Department of State. As a result, the preservation of records from the American posts in European Russia was haphazard.

By contrast, the situation in Siberia was different, and only through chance did the bulk of the records from the posts there not survive. Consul General Harris recognized that he was operating in a fluid situation and by operating from a mobile office on a train took steps to ensure that he and his subordinates were able to secure their files without resort to intentional destruction. By the time that American offices were closing for good, the department recognized the need for specific instructions regarding the preservation of post records. As a result, most files were evacuated, only to fall victim to the earthquake and fire in Tokyo.

While it is true that many records from American posts in Russia no longer exist, still more have survived. What has been preserved provides a unique and important perspective on events in Russia, American relations with that country, and the work and activities of the American diplomatic and consular officers who served there. Despite the incomplete nature of the records, any researcher interested in those topics will find the surviving records of interest and use in their studies, thus demonstrating that the department's actions to locate and preserve the records was worthwhile.

David A. Langbart is an archivist on the staff of the Life Cycle Management Division, National Archives and Records Administration. He holds primary responsibility for the archival appraisal of records of the Department of State as well as several agencies in the Intelligence Community. Prior to joining the Life Cycle Management Division, he worked in NARA's Judicial and Fiscal Branch, Diplomatic Branch, and Military Field Branch.

Notes

The author acknowledges the assistance of Anne L. Foster, William P. Fischer, Milton O. Gustafson, M. Philip Lucas, and Ronald E. Swerczek.

1. The Central Foreign Policy File is part of Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State. The central file has gone through several incarnations since 1789. From that point to 1906, the records were filed chronologically by type of document under three broad heading: diplomatic correspondence, consular correspondence, and miscellaneous correspondence. From 1906 to 1910, the records are arranged in case files arranged numerically by assigned number, and are known as the "Numerical and Minor Files." From 1910 to 1963, the records were filed by subject under a predetermined decimal classification scheme (the "Central Decimal File"). There were two basic versions of the decimal classification system, the first used from 1910 through 1949 and the second from 1950 to 1963. From 1963 to 1973, the records were arranged according to a predetermined subject-numeric classification scheme. Since 1973, the records consist of a mix of microfilm of telegrams and hardcopy documents and the electronic text of telegrams and indexing information for all the records. The records of diplomatic and consular posts compose Record Group 84: Records of Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State. The comment about the value of post files comes from Norman E. Saul, War and Revolution: The United States and Russia, 1914–1921 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2001), p. xiii.

2. For an overview of early preservation efforts relating to post records, see Meredith B. Colket, Jr. "The Preservation of Consular and Diplomatic Post Records of the United States," The American Archivist 6 (October 1943): 193–205.

3. Unnumbered despatch from Embassy Russia, Mar. 17, 1918, Department of State Central Decimal File 124.61/42, Record Group (RG) 59, National Archives (NA).

4. George F. Kennan, Russia Leaves the War, vol. 1 of Soviet-American Relations, 1917–1920 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), p. 438.

5. Telegram #40 from Consulate General Moscow through Paris, July 24, 1918, File 701.0061/17, RG 59, NA. The nine countries represented were the United States, Japan, China, Siam, Brazil, France, Italy, Belgium, and Serbia.

6. Unnumbered despatch from Consulate General Singapore, Oct. 28, 1929, File 124.612/113, RG 59, NA.

7. Nielsen to the Department of State, Oct. 21, 1929, File 124.612/99, RG 59, NA.

8. Despatch #929 from Consulate General Prague, Dec. 11, 1929, File 124.616/50, RG 59, NA.

9. Despatch #1640 from Consulate Canton, Nov. 26, 1929, File 124.612/109, RG 59, NA.

10. Ibid.; Despatch #962 from Consulate General Hong Kong, Dec. 5, 1929, File 124.612/110, RG 59, NA.

11. Despatch #1386 from Embassy Russia, July 15, 1918, File 861.00/5074. This document is found in "Papers Relating to the Sisson Documents," RG 59, NA.

12. Memorandum, Division of Russian Affairs to the Consular Bureau, Dec. 19, 1919, File 125.1462/27, RG 59, NA.

13. DeWitt C. Poole to Department of State, Mar. 9, 1920, File 124.615/88; unnumbered telegram to Consulate London, Dec. 22, 1919, File 125.1462/26a; and unnumbered despatch from Consulate London, Jan. 3, 1920, File 125.1462/29, RG 59, NA.

14. See bound volume of 1918 telegrams of the embassy in Russia for undated Division of Near Eastern Affairs—Russian Section notes. Those notes had to have been placed in the volumes before August 13, 1919, when the Division of Russian Affairs was established.

15. Department of State to David R. Francis, Apr. 26, 1923, File 124.611/33b; memorandum, J. Butler Wright to the Secretary of State, June 12, 1925, File 124.613/449; Caldwell to Webster, July 30, 1925, and Apr. 20, 1926, File 124.613/442, RG 59, NA.

16. For example, see Department of State to Consulate Helsingfors, Aug. 24, 1925, File 124.613/453, RG 59, NA.

17. Despatch #20 from Consulate General Vienna, Nov. 8, 1929, File 124.612/104, RG 59, NA.

18. Despatch #8 from Consulate Vladivostok, Sept. 14, 1920, File 125.4852/13; despatch #43 from Consulate Vladivostok, Dec. 14, 1922, File 125.4852/21, RG 59, NA.

19. Department of State to Consulate Vladivostok, June 11, 1920, File 125.4852/13, RG 59, NA.

20. Telegram #7 from Vladivostok, Feb. 22, 1923, File 123T79/71; unnumbered telegram to Embassy Japan for relay to Vladivostok, Mar. 2, 1923, File 123T79/71, RG 59, NA. Tuck reported that the office would be permitted to function although not recognized as an "official consulate."

21. Telegram #48 from Embassy Japan, May 3, 1923, relaying telegram of May 1, 1923, from Consulate Vladivostok, File 125. 977/13; telegram #43 to Embassy Japan, May 8, 1923, for relay to Vladivostok, Files 125.977/13, RG 59, NA.

22. Telegram #40 from Tokyo, Apr. 20, 1923, relaying telegram of Apr. 19, 1920 from Consulate Vladivostok, File 125.977/10, RG 59, NA.

23. The records Tuck took to Tokyo included the Vladivostok consulate's basic files for the period 1918 to 1923, War Trade Board files for 1918–1919, Inter Allied Railway Committee files for 1919–1921, files of the consular offices in Siberia deposited by Ernest Harris, and some files from the consulate general in Moscow and the embassy. The records left behind were stored, along with equipment from the consulate, in two rooms rented from the Sinkevitch brothers. Tuck reported as follows on the storage conditions: "In both rooms the windows were boarded up from the inside and bound with strips of iron; the doors were locked and sealed, and notes posted up in English and Russia 'This Room contains Property of the Government of the United States of America'; the doors of both rooms were then nicely boarded up and painted, making the appearance of a wall, and quite impossible to enter except by violence." Telegram #48 from Embassy Japan, May 3, 1923, relaying telegram of May 1, 1923, from Consulate Vladivostok, File 125. 977/13; Telegram #57 from Embassy Japan, May 19, 1923, File 123T79/83; Despatch #145 from Consulate Vladivostok, May 31, 1923, File 125.9771/30; Despatch 149 from Consulate Vladivostok (at Tokyo), June 13, 1923, File 125.9772/117; Despatch 4648 from Consulate Harbin, Oct. 20, 1928, File 125.9771/43, RG 59, NA.

24. Division of Eastern European Affairs Chit, Sept. 4, 1923, File 125.9772/119, RG 59, NA. The files of the embassy itself survived since they were stored in a fireproof vault. Not all documentation from the consulate general and subordinate posts in Siberia was lost. Consul General Harris kept copies of some documents in his "personal" papers and took them back to the United States in 1920. Those files are now in the collection of the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University.

25. Memorandum by Lehrs enclosed with unnumbered despatch from Legation Latvia, June 15, 1930, File 124.612/112, RG 59, NA. Lehrs at one time served as a vice consul in the Moscow consulate general.

26. Despatch #2646 from Consulate Riga, Feb. 8, 1924, File 125.6312/72, RG 59, NA.

27. Telegram #238 from Consulate Riga, May 28, 1923, and unnumbered telegram Consulate Riga, May 29, 1923, File 125.6312/70, RG 59, NA. Soviet officials insisted on having the safe opened before shipment. Since the keys were not available, the safe was broken open and found to contain only two keys.

28. Department of State to International Harvester Company, May 27, 1925, File 125.6316/47a, RG 59, NA.

29. International Harvester Company to the Department of State, July 30, 1925, File 125.6316/49, RG 59, NA.

30. Department of State to George W. Williams, Nov. 10, 1925, File 125.6316/49, RG 59, NA. Other Foreign Service Officers contacted included Ernest L. Harris, Alfred, Thomson, DeWitt C. Poole, David B. Macgowan, and S. Pinkney Tuck.

31. G. W. Williams to the Department of State, May 1, 1926, File 125.6316/53, RG 59, NA.

32. Despatch #1265 from Legation Persia, Dec. 28, 1925, File 703.9161/1; despatch #429 from Legation Persia, Sept. 8, 1927, File 125.1812/34, RG 59, NA.

33. Division of Eastern European Affairs memorandum, Dec. 8, 1927, File 125.1812/34, RG 59, NA.

34. Instruction #602 to Embassy Persia, June 16, 1928, File 125. 1812/34; despatch #694 from Embassy Persia, June 27, 1931, File 125.1812/39, RG 59, NA.

35. Despatch #28 from Embassy Japan, Jan. 28, 1926, File 124.616/36; despatch #2145 from Embassy Germany, Apr. 8, 1927, Files 124.616/37; unnumbered despatch from Embassy Germany, March 29, 1928, Files 124.616/40 RG 59, NA.

36. Despatch #306 from Embassy Japan, Oct. 12, 1926, File 125.9772/126, RG 59, NA.

37. Department of State to Arkadij Lapin, Warsaw, Poland, Aug. 24, 1929, File 125.6315/138; Department of State to Senator Theodore E. Burton, Aug.12, 1929, File 361.1121 Caton, William/13, RG 59, NA.

38. Memorandum, Division of Eastern European Affairs to Division of Foreign Service Administration, May 17, 1929, File 124.616/40-1/2, RG 59, NA.

39. Memorandum, Division of Eastern European Affairs to Division of Foreign Service Administration, May 7, 1929, File 125.6315/138, RG 59, NA.

40. Memorandum, Consular Bureau to Division of Eastern European Affairs, Oct. 1, 1929, File 124.612/99a, RG 59, NA.

41. Earl L. Packer memorandum, Division of Eastern European Affairs, Sept. 3, 1929, File 861.01/1510-1/2, RG 59, NA. Earl L. Packer letter to author, July 12, 1981.

42. Chit, Division of Eastern European Affairs to Division of Foreign Service Administration, Oct. 10, 1929, and Department of State to Orsen Nielsen, Oct. 14, 1929, File 124.612/99a, RG 59, NA.

43. Department of State to Orsen Nielsen, Oct. 14, 1929, File 124.612/99a; Department of State to DeWitt C. Poole, John Randolph, Hooker A. Doolittle, Alfred T. Burri, Alfred R. Thomson, David B. Macgowan, Ernest L. Harris, Felix Cole, Roger C. Tredwell, Frank C. Lee, Douglas Jenkins, and John K. Caldwell, Oct. 22, 1929, File 124.612/99b, RG 59, NA.

44. See the following documents: 124.612/99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 112, and 113, RG 59, NA.

45. Despatch #4648 from Harbin, Oct. 20, 1928, File 125.9771/43; unnumbered instruction to Harbin, Dec. 13, 1928, File 125.9771/43, RG 59, NA. The information came from the Sinkevitch brothers to whom the department had continued to pay rent for the two rooms used to store the records and property of the consulate. Since the brothers were no longer providing that service after the date of the seizure, the department ceased paying the rent.

46. Despatch #1045 from Embassy Tokyo, Dec. 19, 1928, File 125.9772/128, RG 59, NA.

47. Instruction 505 to Embassy Tokyo, Feb. 28, 1929, File 125.9772/128; Division of Foreign Service Administration memorandum, Jan. 18, 1929, File 125.9772/129, RG 59, NA.

48. Despatch #4800 from Consulate Harbin, Apr. 1, 1929, File 125.9772/130, RG 59, NA.

49. Division of Eastern European Affairs memorandum, June 26, 1929, File 125.9772/132, RG 59, NA.

50. Report, Division of Foreign Service Administration, May 12, 1932, File 124.616/40-1/2, RG 59, NA.

51. Memorandum, Division of Foreign Service Administration Sept. 26, 1932, File 124.612/115A, RG 59, NA.

52. Telegram #386 to Legation China, Dec. 2, 1933, File 124.616/41A; telegram #305 to Embassy England, Dec. 2, 1933, File 124.616/41B, RG 59, NA. The department directed those two posts to repeat the message to all consulates in China and to all missions in Europe, including Istanbul, respectively.

53. Despatch #378 from Embassy England, Dec. 5, 1933, File 124.616/43, RG 59, NA.

54. Despatch #7606 from Consulate Istanbul, Dec. 23, 1933, File 125.1816/16, RG 59, NA.

55. Despatch #120 from Consulate General Oslo, Dec. 28, 1933, File 125.6366/1, RG 59, NA.

56. Despatch #65 from Legation Latvia, Jan. 19, 1934, File 124.616/65, RG 59, NA.

57. Copy of 125.2982/14 in NARA finding aids for Record Group 84.

58. Telegram #2 from Legation Persia, Jan. 27, 1934, File 125.1812/41, RG 59, NA.

59. Memorandum, Division of Eastern European Affairs to Division of Foreign Service Administration, Feb. 1, 1934, File 125.1812/41, RG 59, NA.

60. Despatch #109 from Consulate Bucharest, Apr. 11, 1934, File 125.1812/41, RG 59, NA.

61. Instruction #87 to Embassy USSR, May 22, 1934, File 125.1812/42, RG 59, NA.

62. Despatch #22 from Consulate General Moscow, May 3, 1934, Department of State to Consulate General Moscow, June 25, 1934, File 125.6312/97, RG 59, NA.

63. Division of Foreign Service Administration memorandum, Jan. 23, 1932, File 124.612/99, RG 59, NA.

64. Telegram 931 from Embassy China, Nov. 13, 1931, File 125.9772/134, RG 59, NA.

65. Despatch 5807 from Consulate General Harbin, July 14, 1933, copy in Diplomatic Branch finding aids for RG 84.

66. Rumors that the Bolsheviks had raided and sacked the offices of the former embassy in Petrograd came soon after the 1918 break in relations. The first reports arrived in July and September 1919, when the consulate at Viborg, Finland, reported receiving information that the Bolsheviks had entered all foreign embassies and legations in Petrograd. In November 1921, a former Red Army soldier reported on the removal of the embassy's furnishings, the throwing of books, papers, and documents into the yard, and the use of military attaché reports and embassy despatches for cigarette paper. Telegram #69 from Consulate Viborg, July 25, 1919, File 124.61/54; despatch #16 from Consulate Viborg, Sept. 6, 1919, File 124.61/59; despatch #288 from Consulate Reval, Nov. 4, 1921, File 124.61/62, RG 59, NA.

67. The story of Ward's discovery is found in his report to the Department of State. See Despatch #477 from Embassy USSR, Mar. 29, 1935, File 124.612/375, RG 59, NA. Also see Harold D. Langley, "The Hunt for American Archives in the Soviet Union," The American Archivist 20 (April 1966): 265–275. The article describes only Ward's discovery of the records of the embassy in Petrograd.

68. Circular, "Return of Russian Records and Archives," Oct. 14, 1935, File 124.616/147A, RG 59, NA.

69. National Archives Identification Inventory, Feb. 1, 1938, File 116/372, RG 59, NA.

70. Memorandum by the Legal Adviser, Sept. 4, 1936, File 300.11/946-1/2, RG 59, NA.

71. NARA Accession Dossier NN3-84-91-2. See also "From Petrograd of 1917, Musty Consular Files," New York Times, Dec. 7, 1990, p. A15. The records include a particularly intriguing file entitled "Revolutionary Movement in Petrograd" covering the period from March to December 1917.

72. Telegram 562 to Embassy Sweden for delivery to Ambassador Francis, Feb. 25, 1918, File 124.61/29b, RG 59, NA.