Face to Face with History

Fall 2009, Vol. 41, No. 3

By Jill L. Newmark

More than 180,000 African Americans—some free born, some escaped slaves—served in the Union Army during the Civil War, but only 13 of them tended to the wounded as surgeons.

Few personal accounts by these surgeons exist, and much of their story has remained hidden, but many clues exist in the thousands of documents and records in the National Archives.

By piecing together these clues—from existing medical personnel files, contract surgeon records, pension files, and other records in the Archives—their stories emerge and their voices can be heard.

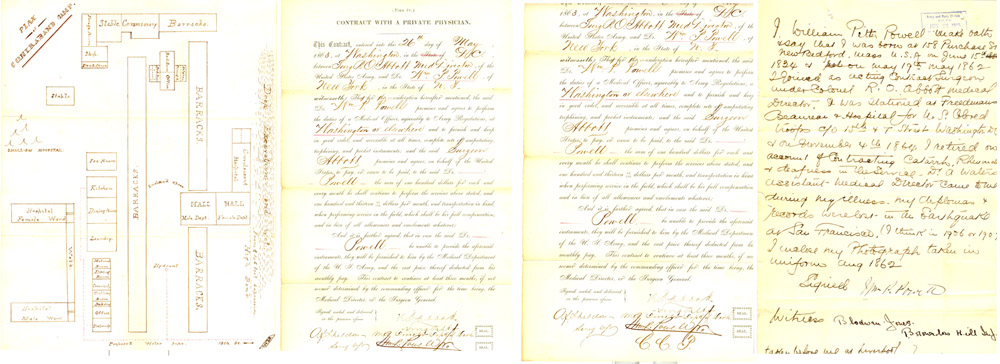

And occasionally, there is a rare moment when a piece of history not known to even exist reveals itself. Such was the case when a 146-year-old photograph of Army surgeon William P. Powell, Jr., was found among the many pages of depositions and documents in his pension file. The photograph is both unusual and special since images of black Civil War soldiers are rare, and those of black Civil War surgeons even harder to find.

The black-and-white photograph reveals a 29-year-old man dressed in a military uniform with his cap on a table beside him. As he rests his arm on the table, legs crossed, he projects an air of confidence and pride. This never-before-published photograph finally puts a face with a name and helps us see the man behind the story.

William P. Powell, Jr., was free born of a black father and a Native American mother in Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1834. His father, William P. Powell, Sr., was a staunch abolitionist and operated several boarding houses for black seamen in Bedford and New York City, providing refuge for tired sailors and fugitive slaves. While living in New York with his family, the younger Powell found work as an apothecary. This piqued his interest in becoming a physician.

By 1851, William P. Powell, Sr., decided to relocate his family to England to escape the harsh fugitive slave laws, which he described as a declaration of war against the "free coloured population" in a letter he penned to the abolitionist newspaper the National Anti-Slavery Standard. The younger Powell spent much of his young adult life living in Liverpool, where his father had established a seaman's boarding house and helped newly arrived fugitive slaves find lodging and work. It was while living in England that he received his medical training from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in London. Whether Powell actually received a medical degree is uncertain, but upon his return to New York with his family in 1861, he began practicing medicine.

With the outbreak of the Civil War that year, many Americans sought ways to participate in the war effort. The opportunity to serve was limited for African Americans until 1863, when dwindling Union resources convinced the government to begin the recruitment of African American soldiers. In May of that year, Powell applied for and was offered a contract with the United States Army to serve as an acting assistant surgeon. He was assigned to the Contraband Hospital for fugitive slaves and black soldiers in Washington, D.C., under the direction of Maj. Alexander T. Augusta, the first African American medical officer in the Union Army and the first surgeon-in-chief of this hospital. Powell served alongside other African American surgeons including Anderson R. Abbott, Benjamin A. Boseman, and John H. Rapier. In October 1863, Augusta left the hospital to muster in with his regiment, the Seventh U.S. Colored Infantry, leaving Powell in charge.

Powell's leadership of the Contraband Hospital lasted only one year. During that time he faced many challenges both administrative and personal. He was troubled by accusations from some nurses and surgeons of reckless drinking habits and questionable treatment of patients. These charges were commonly brought against African American Army surgeons during the war as a result of the widespread prejudice they faced. Despite these accusations, Powell was still seen as a good doctor by many patients and nurses and served out his time until his departure in November 1864.

After leaving the Contraband Hospital, Powell continued to practice medicine as a civilian and by 1891 had retired from the profession due to declining health and disability. The loss of his medical credentials during an earthquake in San Francisco hindered his ability for employment as a physician and added to his decision to retire. With no other means of support, he filed a pension application, convinced of his worthiness to receive a government pension based on his disability and Army service. He would spend the next 24 years petitioning the government to approve his application, even writing to Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt asking for their support.

Powell returned to England in 1902 to tend to his dying brother while continuing to pursue his claim for a military pension. Despite his determination and perseverance, he was unsuccessful. His pension was denied based on insufficient medical evidence of his disability and his status as a contract surgeon, not a commissioned military officer. Powell remained in England until his death in 1915 at the age of 81, having spent his last years as an invalid confined to a home for the aged and infirmed.

William P. Powell, Jr.'s story is just one of the many stories of African American surgeons that are revealed through the documents found at the National Archives. These records provide a glimpse into the shared experiences of these men and open a door into this rarely studied part of Civil War history.

Jill L. Newmark is exhibition specialist and registrar in the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland. She has curated several exhibitions for NLM including "Opening Doors: Contemporary African American Academic Surgeons" and Everyday Miracles: Medical Imagery in Ex–Votos"and is currently working on a project exploring the role of African Americans in Civil War medicine.

Note on Sources

Cynthia G. Fox and Dennis Edelin of the Textural Archives Division of the National Archives in Washington, DC, were very helpful in locating records that assisted in the development of this article.

There are 13 known African American men who served as surgeons during the Civil War. They are Alexander T. Augusta, Anderson R. Abbott, Benjamin A. Boseman, Cortland Van Renssalear Creed, John Van Surly DeGrasse, William Baldwin Ellis, J. D. Harris, William P. Powell, Jr., Charles Burleigh Purvis, John H. Rapier, Jr., Willis R. Revels, Charles H. Taylor, and Alpheus W. Tucker. Only two received military commissions as surgeons—Augusta and DeGrasse; the remaining 11 were private physicians hired by the Union army as contract surgeons. Only four photographs of African American surgeons in Union uniforms are known to exist: Abbott, DeGrasse, Rapier, and Powell.

Primary source materials in Record Group 94, Entry 561, Records Relating to Medical Officers and Physicians, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780’s–1917, National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, D.C., include files for Powell, Abbott, Boseman, and Rapier. Among the documents found in Entry 561 of this record group are letters, physician contracts, oaths of allegiance, and records of service related to each physician. Powell's pension application file (#1065790) is found in Records of the Veterans Administration, RG 15, NAB.

The U.S. Census of 1850 indicates that at the age of 16, Powell was employed as an apothecary in New York City. Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, New York, ward 4, p. 239, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group (RG) 29.

William P. Powell, Sr.'s letter against fugitive slave laws was published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard, October 30, 1851.