How an eagle feels when his wings are clipped and caged

Relocation Center Newspapers Describe Japanese American Internment in World War II

Winter 2009, Vol. 41, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By Rebecca K. Sharp

While interned at the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho, newspaper staff reporter Kimi Tambara wrote an open letter in the Minidoka Irrigator to her friend Jan. She recalled Christmas 1941, just weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

. . . another thought . . . coincident with the crackling noise of the firecrackers popping around Lower Chinatown, a low voice 'You damn Jap-you! By gosh, the government should put every damn one of you in concentration camps'—I remember the cold shiver that ran up my spine, transforming the humid, warm air of a July night into the bitter cold of winter. You and I, Jan, tried to laugh it off, because somehow, it seemed ridiculous. The freedom of life and liberty was so much a part of us that the idea of confinement had never once occurred to us.

Tambara also described her feelings about internment:

[T]his life behind a fence is not a pleasant one, but nothing can be pleasant in these times, could it? I can now understand how an eagle feels when his wings are clipped and caged. Beyond the bars of his prison lies the wide expanse of the boundless skies, flocked with soft clouds, the wide, wide, fields of brush and woods—limitless space for the pursuit of Life itself. 1

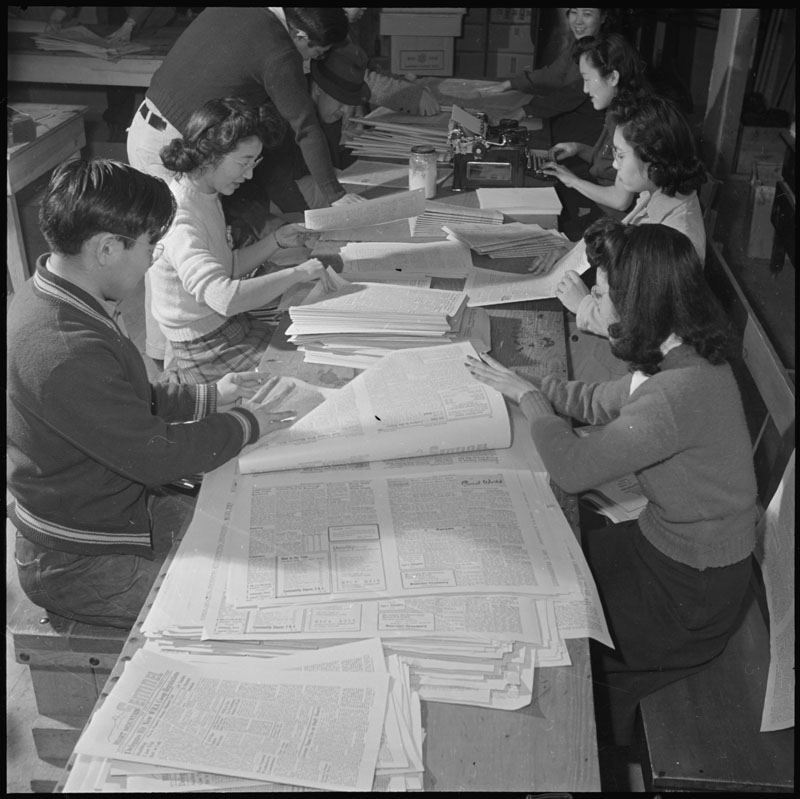

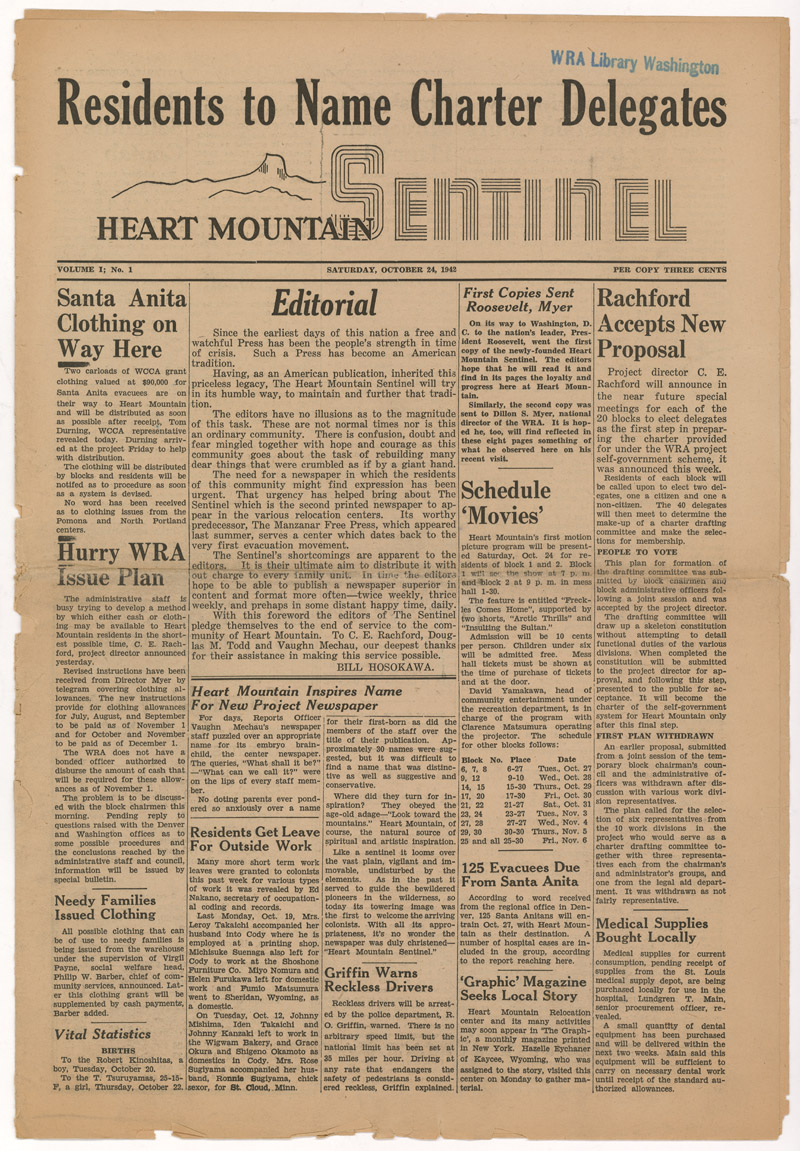

The Japanese American 2 internees published newspapers that provided general information about their community as well as specific individuals. Publication frequency varied from newspaper to newspaper. Some newspapers were published once a week, while others were published biweekly, triweekly, or even six times a week. The publication frequency of a particular newspaper often changed over time.

Two and a half months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which gave the secretary of war and military commanders the authority "to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded." 3 This order gave the U.S. Army the authority to forcibly evacuate the Japanese American population from the designated military areas along the Pacific Coast between the latter part of March and May 1942. 4

The Japanese Americans could bring only what they could carry—clothes, plates, cups, utensils, linens, toiletry items, and mementos—to the designated collection points. With less than a week to sell their businesses, houses, and valuables, they had no time to get things in order. The evacuees were moved to 16 assembly centers. Many of the assembly centers were located on fairgrounds and racetracks, where the living conditions were overcrowded and unsanitary.

Beginning in May 1942, the War Department transferred the Japanese Americans to 10 War Relocation Authority (WRA) relocation centers: Central Utah (Utah), Colorado River (Arizona), Gila River (Arizona), Granada (Colorado), Heart Mountain (Wyoming), Jerome (Arkansas), Manzanar (California), Minidoka (Idaho), Rohwer (Arkansas), and Tule Lake (California). Under guard and surrounded by barbed-wire fences, the internees lived in cramped barracks sharing communal toilets, showers, and mess halls. Privacy was nonexistent. The relocation centers mirrored small communities with churches, hospitals, libraries, post offices, and schools. The WRA allowed some internees to leave for temporary seasonal agricultural work. Others attended college, served in the military, or obtained outside employment. Some of the internees remained in the WRA relocation centers until they closed in 1946.

Relocation Center Newspapers

The newspapers served as a means for disseminating WRA rules, regulations, and surveys. The WRA initially banned the use of Japanese in the newspapers, but later issues sometimes included Japanese-language inserts. Newspaper articles cover a wide range of topics including daily activities, beauty tips, diet and nutrition, crime and law enforcement, education, hobbies, social activities, and sports. The newspapers reported on military service, outside employment opportunities, and vital statistics as well as rumors that were circulating throughout the relocation centers. The newspapers also described culture shock, a consequence of internment, forced assimilation, and a constant reminder how their lives had changed. Since the newspapers were censored, the staff avoided direct criticism of the federal government. 5

Artwork, maps, photographs, and weather reports offer a glimpse at the relocation center environment. On occasion, the newspapers include the artwork, articles, letters, poems, and short stories submitted by internees or former internees who were attending colleges and universities, working outside the relocation center, or serving in the military. In addition to relocation center news, the newspapers also conveyed national and world news.

Vital Statistic

The newspapers published lists of births, marriages, and deaths in the relocation centers. The lists provide minimal information about the individuals. For example, the birth lists typically record the baby's sex, birth date, and the parents' names, and in some, but not all cases, the baby's name. The newspapers briefly announced engagements, marriages, and milestone wedding anniversaries as well as obituaries. Longer articles about a newborn may list the attending medical staff, while an article about a wedding may include the name of the presiding religious official.

The newspapers usually ran feature articles about the first birth, marriage, and death that occurred at the relocation center. Yuki Shiozawa and Taro Katayama were the first couple to wed at the Central Utah relocation center. The Topaz Times reported that several musical performances preceded the wedding, including Goro Suzuki's (the bride's cousin) rendition of the song "At Dawning." Protestant minister Rev. Joseph Tsukamoto officiated; Yuki's father, Tetsushiro Shiozawa, gave her away; and Taro's best man was his brother, Jerry Katayama. The article also describes the couple's wedding attire:

The bride, with a "Victory" pompadour hairdress, wore a wine-colored velveteen dress and accessories with 1 strand of pearls. She wore an orchid corsage rounded off with white bouvardias. The benedict [bridegroom]wore a navy blue tailored suit.

The article also puts the wedding in the context of internment:

Prior to evacuation the bride was a Civil Service stenographer in the Alameda County Charities Commission in Oakland. The bridegroom, formerly of Salt Lake City, is a graduate of the University of Utah, and was working on a San Francisco paper before the evacuation. He was also the editor of the Tanforan Totalizer [an assembly center newspaper]. They are "at home" in 36-12-A [relocation center barracks address] until Thursday. 6

Living Quarters

In addition to general articles about the barracks and community living, a small percentage of the articles show the creative ways in which individuals modified their living quarters. Yoshimatsu Mukai, an internee at the Rohwer relocation center in Arkansas, decorated the exterior of his barracks with wood carvings of a monkey and birds. The article describes Mukai's personality: "He is very modest about his work and laughingly replies, ‘One minute,' when asked how much time is required to make each animal." 7

The Heart Mountain Sentinel ran a series of articles that showed different barracks to give readers interior decorating ideas. These articles include sketches of the featured barracks, such as Mr. and Mrs. Bob Sato's "apartment":

When is a closet not a closet? We have been informed it was intended for a coal bin, but Mrs. Sato has cleverly converted her "closet" to a den or nook, with card table and chairs. The chairs are fashioned out of orange boxes, draped in stripped denim. The upper part of the den was made for storage space, covered with monks cloth, the same material used for her dressing table and closet which was built in one corner. Adding life to the otherwise drab monks cloth is a gay yellow, red, and blue bias tape trim on the hem of the drapes.

The den is made cozy with lights. For [the] lamp shade, Mrs. Sato used the white corrugated paper which came with the mail order wrappings.

An oval mirror adds to the modernistic touch of her spacious dressing table which was fashioned out of left-over celotex. Three shelves on each side, 18 inches deep, hold linens, clothing, shoes, etc. 8

Artwork

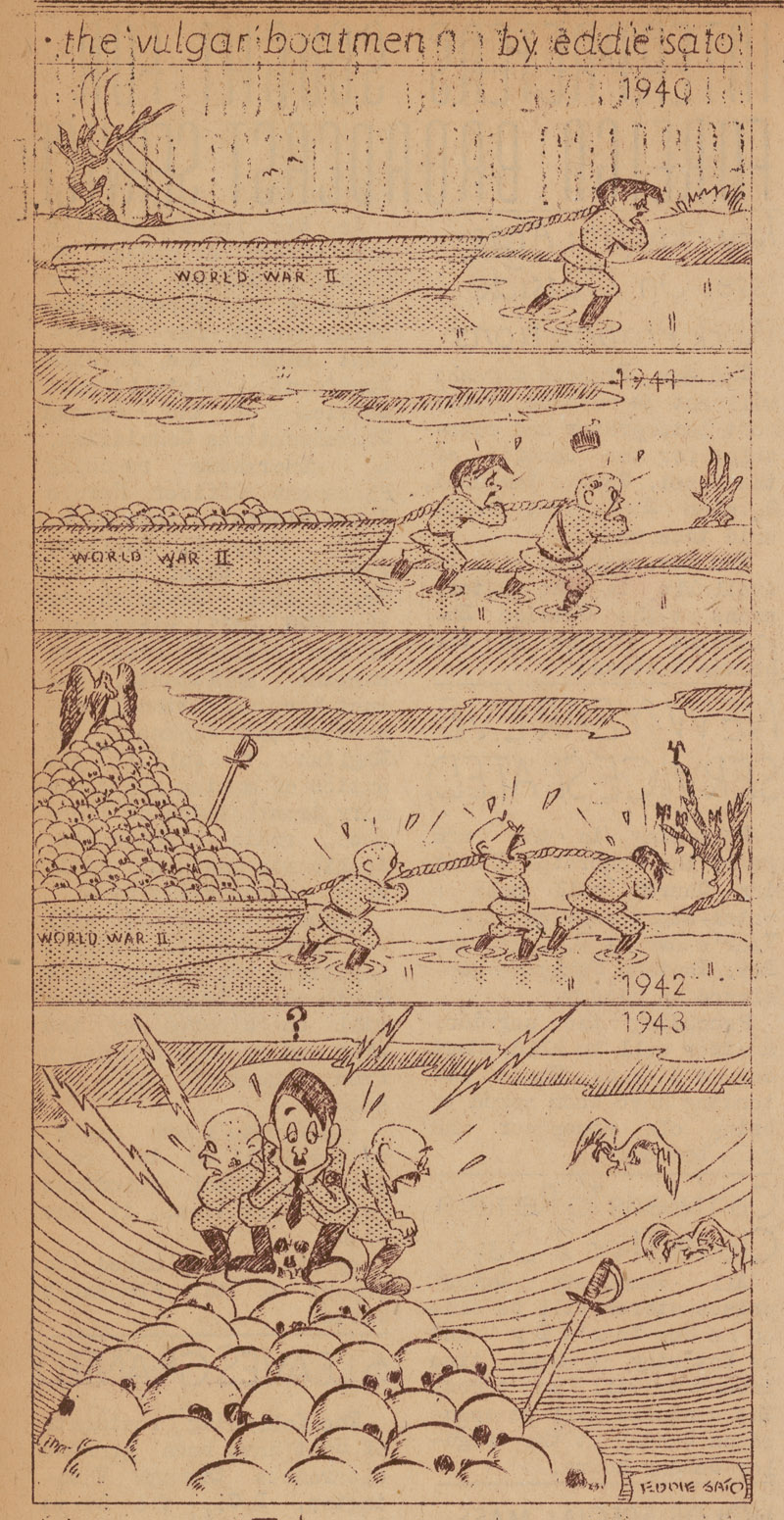

Despite the difficult living conditions, people continued to express themselves artistically. Comic strips and other works of art appear in most WRA relocation center newspapers. One example is the artwork of Eddie Sato, a staff artist for The Minidoka Irrigator. Sato, a talented political cartoonist, created a comic strip character that he considered calling Potato, but the newspaper decided to run a character-naming contest. Three articles about the contest provide information about Sato, the cartoon character, and the Minidoka community. The November 7, 1942, issue announced Yasuko Koyama's winning submission, Dokie. 9 Dokie first appears to be an ordinary comic strip character, but a closer look at the strips reveals that Sato captured the reality of internment. In May 1943, Sato left the Minidoka relocation center to serve in the military. Although he was no longer interned, the newspaper occasionally ran articles about him, including information about his winning art contest submissions and his return visit to Minidoka. 10 Eddie Sato is just one example of the numerous Japanese American internees who went to war for a country that had confined its loyal citizens behind barbed wire fences.

Availability of the Records

The publications created by the Japanese American internees, including church papers, newspapers, and school papers, are among the records of the relocation centers (entry 4b) in the Records of the War Relocation Authority (Record Group 210).

The National Archives does not have a complete set of relocation center newspapers. Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project digitized approximately 4,000 newspapers from the 10 WRA relocation centers. Researchers must register (registration is free) to obtain access to Denshō's "Camp Newspapers Collections" Digital Archive ( www.densho.org). 11 The Bancroft Library's (University of California at Berkeley) "Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, 1930–1974," and the Library of Congress's "Japanese Camp Papers" (microfilm number 2022) may have additional newspaper issues.

Entry 4b records have been microfilmed and are available as Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (Microfilm Publication C53). The records are arranged by relocation center; however, the microfilm roll list only records the first and last record that appears on each roll of microfilm. The staff of the National Archives created a finding aid that provides the titles and coverage dates of the church papers, newspapers, and school papers published by the Japanese American internees.

To receive a copy of this finding aid, contact the Archives I Reference Section (NWCT1R), 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408-0001 (e-mail archives1reference@nara.gov). Microfilm Publication C53 is available at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and at the National Archives regional archives in Laguna Niguel, California. For additional information about this microfilm publication, including a digital copy of the microfilm roll list, visit the online microfilm catalog through Order Online at www.archives.gov. The records can be difficult to use because there is no master name index. To locate articles about individuals, researchers need to read the WRA relocation center newspaper of interest.

Although this research can be time consuming, the WRA newspapers provide a contemporary description of the often difficult and desolate conditions of the relocation centers. The newspapers can also show how the Japanese Americans adapted to both the physical and psychological pressures of internment.

Rebecca K. Sharp is an archives specialist in the Archives I Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. She specializes in federal records of genealogical interest.

Notes

The author would like to thank the following staff members for their professional guidance: Rebecca Crawford, John Deeben, Constance Potter, Claire Sadar, Sally Schwartz, Katherine Vollen, William Wade, and Nancy Wing. She would like to acknowledge Michelle Farnsworth for digitizing the original relocation center newspapers described in this article.

1 This letter is part of a special Christmas 1942 issue. See "Irrigator Asks: Contributions for Yule Issue," Minidoka Irrigator, Dec. 12, 1942, vol. I, no. 26, p. 1. Tambara's letter is published as "In This, Our Land," Minidoka Irrigator, Dec. 25, 1942, vol. I, no. 29, p. 7. Both articles are found in Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (Microfilm Publication C53, roll 91), Records of the War Relocation Authority, Record Group (RG) 210.

2 U.S. naturalization laws prohibited Japanese immigrants, the issei, from obtaining United States citizenship. Children of the issei born in the United States, the nisei, were automatically U.S. citizens. Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project emphasizes that "[b]y the time of World War II, most issei had lived in the United States for decades and raised their children here. Although they were technically aliens and ethnically Japanese, many considered themselves permanently settled in the United States . . . [and] had no plans for returning to Japan, and would have become naturalized citizens if that had been allowed." In light of this, the term Japanese American will be used to refer to both citizens and noncitizens. Denshō: The Japansese American Legacy Project web site, Terminology and Glossary section, www.densho.org (accessed June 19, 2009).

3 Executive Order No. 9066, Feb. 19, 1942, General Records of the United States Government, RG 11. Available online at www.ourdocuments.gov (accessed June 12, 2009).

4 Estimates vary from 100,000 to 120,000 interned Japanese Americans. The WRA was established within the Office for Emergency Management on March 18, 1942.

5 The staff usually self censored, but omissions of reports of conflicts between the Japanese American internees and the WRA suggest WRA censorship.

6 "First Wedding Held," Topaz Times, Nov. 17, 1942, vol. I, no. 16, p. 2, Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (C53, roll 10), RG 210.

7 "He Wasn't Stumped," The Rohwer Outpost, Apr. 7, 1943, vol. II, no. 28, p. 4, Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (C53, roll 100), RG 210.

8 "The Social World: Your Home and Mine," Heart Mountain Sentinel, Oct.24, 1942, vol. I, no. 1, p. 3, Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (C53, roll 58), RG 210.

9 For additional information, see the following issues of the the Minidoka Irrigator: "Name Sought for 'Imp' Who Makes Debut," Oct. 21, 1942, vol. I, no. 11, p. 6; "Cartoon Hero Still Nameless, asks Readers to Aid Plight," Nov. 4, 1942, vol. I, no. 15, p. 7; and "Irrigator Mascot Christened," Nov. 7, 1942, vol. I, no. 16, p. 7, all in Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (C53, roll 91), RG 210.

10 "Sounding Off . . . ," Minidoka Irrigator, May 15, 1943, vol. III, no. 12, p. 4; "Four Hunt Entrants in Art Contest Win Honors: Exhibit Sponsored by Friends Ass'n for Ten Centers," Minidoka Irrigator, May 29, 1943, vol. III, no. 14, p. 5; and "Hunt is Home for Shelby Boys," Minidoka Irrigator, Sept. 11, 1943, vol. III, no. 29, p. 3, all in Field Basic Documentation of the War Relocation Authority, 1942–1946 (C53, roll 92), RG 210.

11 To learn more about Denshō's newspaper digitization project, visit www.densho.org and click on "Archive," then "From the Archive," followed by "June 2007—Free Press behind Barbed Wire. Newspapers Published in the Incarceration Camps."