Abraham Lincoln and the Guerrillas

Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1

By Daniel E. Sutherland

Much has been written about Abraham Lincoln as a wartime commander-in-chief. All of these analyses, however, deal with Lincoln’s handling of the conventional war, with armies, navies, grand strategies, and incompetent generals. No scholar has considered the evolution of the President’s response to the irregular war. Not that this is strange, for scholars, until relatively recently, have treated the entire guerrilla conflict as little more than a “side show” of the larger war.

That will no longer do.

A growing body of literature, most of it concentrating on particular communities or regions of the wartime South, have demonstrated the pervasive nature of the guerrilla war. It is time to put Lincoln in the mix.

First, to put things in perspective, it must be explained that far more guerrillas fought in far more places and with far graver consequences than students of the Civil War have supposed. Not just Confederates either, which is the general impression. The results were three distinct yet interconnected guerrilla contests. One was a military affair, with rebel guerrillas confronting and harassing the Union Army. The second was a purely civilian affair, if “civilian” may be applied to bands of armed men who engaged in arson, torture, terror, and murder. These bands were composed of Southern neighbors who had taken rival sides, Unionists and Confederates, and who battled each other to maintain political and economic control of their communities. The third guerrilla contest had even less to do with military operations. Rather, it was simple outlawry, sometimes engaged in by “legitimate” guerrillas, but more often pursued by bands of deserters, draft dodgers, and thugs who held loyalty to no side. Taken together, the three guerrilla conflicts created utter chaos in many parts of the South and went a long way toward crippling Confederate resources and morale.

Lincoln did not have to deal directly with the outlawry, a problem he gladly left to Jefferson Davis. Even so, legitimate rebel guerrillas posed mounting dangers to his army and Southern Unionists. Like nearly all political and military leaders on both sides, Lincoln was surprised by the scope and ferocity of this guerrilla upheaval. Also like many political leaders, he was slow to understand the consequences of an unchecked guerrilla war. As this realization grew, Lincoln either endorsed measures or took independent actions that protected the Union Army and his Southern supporters against rebel guerrillas.

Although he did not appreciate it at the time, the first week of the war showed Lincoln what havoc even relatively small numbers of irregular fighters could cause. Five days after the surrender of Fort Sumter, what authorities called a Baltimore “mob” attacked a Massachusetts regiment as it marched through the city en route to Washington, D.C. The so-called mob might just as easily have been labeled “urban guerrillas.” They threw stones and fired guns at the troops. The soldiers returned fire, the results being a total, for both sides, of 16 dead and 85 wounded, the first casualties of the war. The regiment, which had been summoned by Lincoln to help defend his capital city, made it to Washington the next day, but the countryside between Lincoln’s domain and Baltimore burst into guerrilla activity. The rebels cut telegraph lines, ripped up railroad tracks, and stole the livestock of Southern Unionists. When Lincoln sent troops to restore order, guerrillas attacked Federal patrols, tried to poison the Army’s provisions, entered Union camps as spies, and plotted to kidnap public officials who aided the invaders. Lincoln eventually suspended habeas corpus in the state and arrested disloyal citizens, including members of the state legislature.

Lincoln might easily have taken this to be an isolated incident had not one of the most ferocious of the guerrilla wars then broken out in Missouri. In July 1861, Julian Bates, a son of Lincoln’s attorney general, Edward Bates, reported to his father from their home state, “There will be hard fighting in Missouri, [but] not between the soldiers, & in many of the Counties there will be ugly neighborhood feuds, which may long outlast the general war.” The senior Bates surely passed on to Lincoln this insightful analysis of the dangers that awaited many parts of the South. The attorney general may even have said something along the lines of his warning to Missouri’s new pro-Union provisional governor: “If things be allowed to go on in Missouri as they are now, we shall soon have a social war all over the State.”

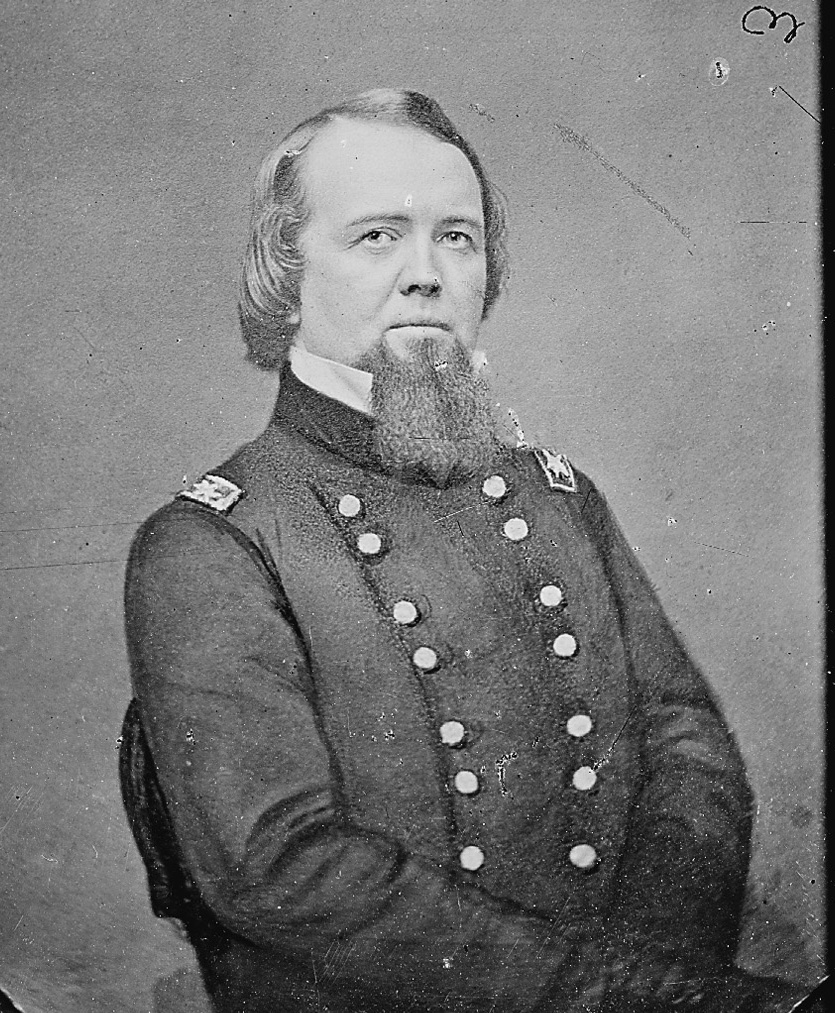

Nonetheless, Lincoln remained slower to see the depths of the situation in the far-off Trans-Mississippi than he had been in his own back yard. Even when Union field commanders attested to the dangers facing loyal citizens and U.S. troops, he was reluctant to endorse punitive measures. In August 1861, the President balked at Gen. John C. Frémont’s decision to court-martial, execute, and confiscate the property of anyone taking up arms against the United States in Missouri. Lincoln foresaw—correctly, as it turned out—the potential for an endless cycle of retaliation and counter-retaliation. By contrast, Missouri Unionists rejoiced at Frémont’s order. A second son of Edward Bates declared, “They [the rebels] should be summarily shot by thousands.” Lincoln let Frémont’s order stand but replaced him a few months later with Gen. David Hunter. More than that, the President told Hunter that the guerrilla threat in Missouri was all but over. “Doubtless local uprisings will for a time continue to occur,” he told the new department commander, “but these can be met by detachments and local forces of our own, and will ere long tire of themselves.”

Not until the summer of 1862 did Lincoln understand the extent of the guerrilla menace, not only in Missouri but across the entire Upper South. The result was a substantial shift in Union military policy. Lincoln abandoned his conservative, conciliatory approach, based on the assumption that the presence of Union troops in overwhelming numbers would be enough to turn Southerners against the rebel government, to adopt the sort of drastic measures Frémont had employed. The shift in policy was not inspired entirely by the guerrilla war. Also pushing Lincoln in this direction was the rising tide of public criticism of his conduct of the conventional war, especially in light of the futility of military operations in the East. With midterm elections due that autumn, he simply had to change public perceptions. Still, effective guerrilla resistance to the Army and the intimidation of the Unionists, whom Lincoln had counted on to lead Southern opposition to the Davis government, clearly influenced his thinking.

Consider how many of Lincoln’s actions in the summer and autumn of 1862 struck directly at rebel guerrillas. Consider, too, how many veterans of the guerrilla war he depended on to implement the new policy. First, Lincoln reassigned John Frémont to command in West Virginia, a cauldron of guerrilla warfare no less roiling than Missouri. Next, he brought Gen. John Pope from the Western theater to command a new Union Army in Virginia. Pope had taken retaliatory measures that exceeded even Frémont’s directives in order to quash guerrilla resistance in his Missouri district. Pope now issued even stricter orders, with the approval of Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, in north-central Virginia. Aimed not only at guerrillas but also at the “evil-disposed persons” who assisted them, Pope’s instructions allowed executions, financial assessments, and the destruction and confiscation of property. By then, Lincoln had also brought Pope’s old department commander in Missouri, Gen. Henry W. Halleck, to Washington as commanding general of all Union armies. Naturally, Halleck added his blessing to Pope’s Virginia policy.

To endorse publicly the new direction announced by Pope and Halleck, Lincoln, toward the end of July 1862, sent a warning to Confederate soldiers and civilians alike. Anyone guilty of “aiding, countenancing, or abetting” the rebel cause, he said, must immediately cease their rebellion or suffer “forfeitures and seizures” of their property. When Andrew Johnson, the President’s newly appointed military governor in Tennessee, asked permission to apply Pope’s orders in that state, Lincoln gave it.

Of course, Lincoln was not asking for wholesale slaughter. Indeed, some politicians complained that the “kind hearted” President commuted or reduced the death sentences of far too many convicted guerrillas. Still, despite his own occasional references to tempering justice with mercy, Lincoln tended to send mixed signals to commanders in the field, perhaps giving them wider latitude than was wise. Explaining the new rules to Gen. John S. Phelps, the military governor of Louisiana and Arkansas, Lincoln wrote, “I am a patient man—always willing to forgive on the Christian terms of repentance. . . . Still, I must save the government if possible. . . . [And] it may as well be understood, once for all, that I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.”

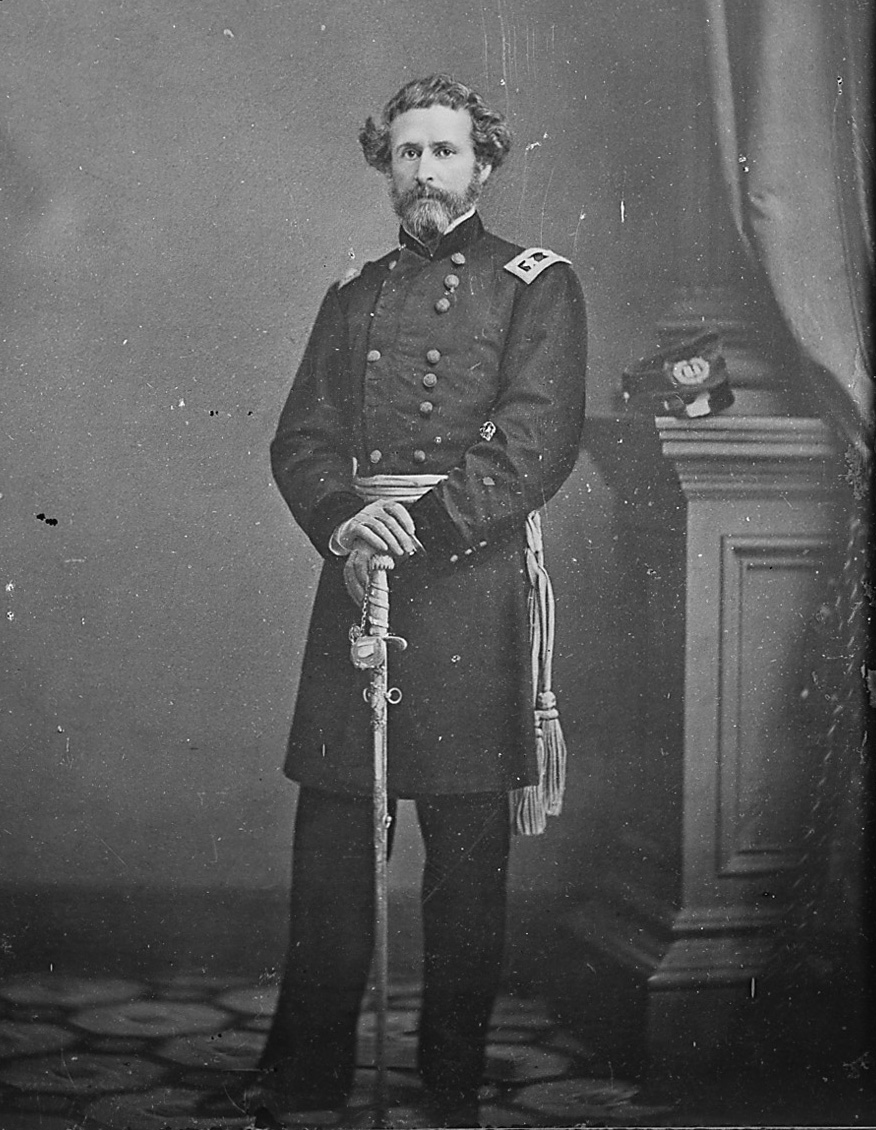

His pragmatic approach soon touched the Deep South, too. When Union troops moved into northern Alabama, they faced the inevitable resistance from rebel guerrillas. When the Army responded by burning the town of Paint Rock, sacking Athens, Alabama, and threatening to execute all saboteurs and guerrillas, Edwin Stanton informed the Army’s commander, Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchel, “Your spirited operations afford great satisfaction to the President.” However, as details about the Army’s mistreatment of noncombatants reached Washington, it became clear that things had gone too far. Mitchel and the officer responsible for sacking Athens, the Russian-born Col. John B. Turchin, were relieved of their commands.

Mitchel, whose more complex case also involved cotton speculation and failure to secure eastern Tennessee, was simply reassigned to South Carolina, but Gen. Don Carlos Buell, the department commander, insisted that Turchin be court-martialed. The court found Turchin guilty of allowing his men to run riot in Athens but decided that his biggest sin had been in not dealing “quietly enough” with the rebels. After initially recommending that he be cashiered from the Army, the court’s majority urged clemency. Lincoln and Stanton concurred, and the President promoted Turchin to general.

As for Buell, who had been a vocal opponent of the new retaliatory policies, he was relieved of his command a few months later. His removal surprised few senior officers, even those who balked at the extreme measures of men like Turchin. One officer, comparing Buell to the Russian, declared, “Turchin’s policy is bad enough; it may indeed be the policy of the devil; but Buell’s policy is that of the amiable idiot.” Buell became the target of a congressional investigation that focused largely on his failure to capture Chattanooga. His principal defense, with which even the commission concurred, was that he had faced formidable opposition from Confederate cavalry and guerrillas. Lincoln also knew that to be true. In early 1863, he complained to Buell’s successor, Gen. William S. Rosecrans, “In no other way does the enemy give us so much trouble, at so little expense to himself, as by the raids of rapidly moving small bodies of men.”

Not that these measures weakened rebel guerrilla resistance to any appreciable degree. Union politicians and generals continued to press for sterner measures, especially in border states, such as Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, where the Federals struggled either to maintain or establish loyal governments. Indeed, there had been instances since the first year of the war of rebel guerrilla operations in the lower Midwest, where governors from Iowa to Ohio worried about the stability and security of their own states.

By the summer of 1863, the Union Army had been recruiting heavily among Southern Unionists for some time. Initially, the authorities scattered these men willy-nilly, to wherever the Army needed more bodies, which was usually far from home. Now, however, some officials realized that Southern Unionists could provide better service in antiguerrilla units assigned to their home regions. Imploring the President to redeploy Tennesseans serving in Virginia in this way, Andrew Johnson explained, “They are willing & more anxious [than Northern volunteers] to restore the government & at the same time protect their wives and children against insult, robbery, murder & inhumane oppression.” Even more dramatically, Johnson recruited local Unionist guerrillas to counter rebel bushwhackers in Tennessee. David C. Beaty, known as “Tinker Dave,” led the deadliest of Johnson’s loyal guerrilla bands. Beaty’s principal opponent was the notorious rebel guerrilla Champ Ferguson.

While seemingly not directly involved, Lincoln no doubt gave his blessing to Henry Halleck’s effort in the summer of 1863 both to legalize the punishment of rebel guerrillas and to curb the excesses of overzealous Union field commanders. Halleck asked German-born Francis Lieber, a professor of political philosophy at New York’s Columbia College, to provide the Army with legal definitions of the variety of guerrillas and ethical guidelines for handling them. Lieber, who had sons fighting in both the Union and Confederate armies, eventually produced two documents, one dealing specifically with guerrillas, the other aimed more broadly at the treatment of noncombatants. Both sets of guidelines were distributed to the Army. The latter, known as the Lieber Code, became the basis for worldwide legal restrictions on the conduct of warfare for a century thereafter.

The same month that Halleck issued Lieber’s code to his armies, Lincoln responded to a crisis in the Trans-Mississippi by endorsing the most repressive U.S. military measure of the war against Southern civilians. At dawn on August 21, 1863, William C. Quantrill, the war’s most notorious guerrilla chieftain, led a raid on Lawrence, Kansas. By mid-morning, his hardened band had burned and looted most of the town and murdered at least 150 men and boys. Gen. Thomas Ewing, Jr., the Union commander responsible for the security of the Kansas-Missouri border, retaliated by expelling nearly all civilians—loyal as well as disloyal—from three Missouri counties and part of a fourth. The order uprooted thousands of people from the heart of Quantrill’s domain and produced untold hardship, but Northern military and political leaders thought it necessary. Gen. John Schofield, Ewing’s department commander, approved the drastic policy, as did Halleck, Stanton, and Lincoln.

Lincoln’s climactic confrontation with the guerrilla war came in the summer of 1864. Believing he could not possibly be reelected that autumn if rapid strides were not made toward defeating the Confederacy, the President kept a particular eye on the success of his armies against rebel irregulars. No state caused more concern than his own home of Kentucky. Besides having known little respite from guerrilla action, the Bluegrass State had served as a springboard for guerrilla raids into Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. In the summer of 1864, Gen. William T. Sherman, about whom much could be said in telling the wider story of the guerrilla war, demanded that Gen. Stephen B. Burbridge, the department commander in Kentucky, remedy the situation. Concerned primarily about the security of his supply lines as he drove toward Atlanta, Sherman ordered Burbridge to take drastic steps to eliminate the “anarchy” in Kentucky. Outlining a plan of action for the overly cautious general, who was a native of the state, Sherman reminded him that guerrillas were “not soldiers but wild beasts unknown to the usages of war.” Burbridge must arrest any man or woman suspected of encouraging or harboring guerrillas, Sherman insisted.

Burbridge did as he was told, and to wonderful effect. He did not end the guerrilla war in Kentucky. Such notorious characters as Jerome Clark (or “Sue Munday”) and Henry C. Magruder continued to plague the state. However, Burbridge did reduce the anarchy substantially, enough to provide an illusion of peace and security. In doing so, he had asked the President for the power to impose economic sanctions against guerrillas and their supporters. Lincoln not only granted his request, essentially transferring that prerogative from the civil government to the Army, but he also urged Burbridge to act “promptly and energetically” to arrest all “aiders and abettors of rebellion and treason,” regardless of “rank or sex.” In addition, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus in the state, imposed martial law, suspended the amnesty program in Kentucky, and granted permission to arm employees of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, the state’s main artery, with repeating rifles to ward off guerrilla attacks. Mindful of the political dimension of all this, he also sent the Army’s judge advocate general, Joseph Holt, a Kentucky native and close political ally, to monitor the situation.

That same month, July 1864, Lincoln signed one of the few pieces of U.S. congressional legislation to deal with the guerrilla war. The Shenandoah Valley had been another key military target in the summer before the election, but events there had gone badly for the Federals. Confederate general Jubal A. Early, supported by rebel guerrillas leaders John S. Mosby and John H. McNeill, had completely flummoxed Union general David Hunter, to the extent even of slipping past Hunter’s army and threatening Washington, D.C. Anticipating the arrival of untold barbarian hordes, Congress quickly passed and Lincoln signed “An act to provide for the more speedy Punishment of Guerrilla Marauders.”

Lincoln won reelection in 1864, but when he died five months later, the war all but over, the guerrilla conflict had still not spent itself. The Union Army continued to track down, capture, and occasionally accept the surrender of rebel irregulars into October 1865. Indeed, an argument could be made that a guerrilla war against the United States continued in parts of the South for another 12 years. As white Southerners rallied to oppose the congressional Reconstruction policy, paramilitary organizations like the Ku Klux Klan operated against the Army and former Unionists, whose ranks now included ex-slaves. How Abraham Lincoln would have reacted to that guerrilla war remains an open question.

Daniel E. Sutherland is professor of history at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. He is the author or editor of 13 books about 19th-century U.S. history, most recently A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War.

Note on Sources

The archival sources for this article are a combination of personal writings (mostly letters and diaries) by military and civilian participants in the guerrilla war and governmental records. Essential collections in the National Archives include court-martial and civilian commission transcripts in the Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Record Group [RG] 153); correspondence to and from the U.S. and C.S. war departments (Records of the Office of the Secretary of War [RG 107] and War Department Collection of Confederate Records [RG 109], respectively); correspondence, affidavits, and reports in the Union provost marshal records (RG 109, and Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920 [RG 393]); and additional Union Army records (RG 393). The governor and adjutant-general papers in the southern and midwestern states are invaluable for understanding local concerns.

The most important published government documents, as for any Civil War topic, are the U.S. War Department, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), and U.S. Navy Department, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 35 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894–1927). For a complete bibliography and the full story of the guerrilla war, see Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).