Magellans of the Sky

Summer 2010, Vol. 42, No. 2

By Rob Crotty

In 1924, barely a week after four Army Air Service pilots set out from Seattle to be the first people to ever circle the globe by air, the flight commander went missing over the treacherous coasts of Alaska.

The four planes—the Seattle, Boston, New Orleans, and Chicago—had taken off together from Seward to Chignik, but Maj. Frederick Martin's Seattle disappeared into a snow squall a hundred miles from their landing site at the remote Alaskan outpost.

"We had been bucking a head wind most of the way and we had barely enough gas to get us through," wrote Jack Harding, the mechanic aboard the New Orleans, "if we turned back to look for the Major and [Sgt. Alva] Harvey [the Seattle’s mechanic], the whole expedition would run the risk of being wrecked."

Word came over the radio at Chignik that the major had been found and that the Seattle was being towed to the village of Kanatak for repairs by one of the Navy destroyers supporting the flight. Martin explained that he had made a forced landing at Cape Igvak after the Seattle’s oil pressure dropped to zero. A three-inch hole in the crankcase below the number five cylinder had caused the pressure drop, and once it was fixed, Martin would meet up with the other pilots at Dutch Harbor.

The other pilots pressed on from Chignik out into the Aleutian Islands outpost. They made repairs on their Liberty engines and prepared to make the flight across the Pacific to Japan as soon as the Seattle arrived. After a week they received news that the weather at Kanatak had finally cleared. "With a little good luck now, [Martin] and Harvey ought to be with us in a day or so, and then we'll be off for Japan," wrote Leslie Arnold, mechanic for the Chicago.

They waited a week. Martin and Harvey never came.

The aerial circumnavigation of the planet was the latest in a global pursuit to conquer the skies. Since the Wright brothers at the turn of the century, flying had become a hobby of nations, and the rush of aerial developments during World War I had turned hobby to obsession. Britain, France, Italy, Argentina, and Portugal were all developing strategies to make their pilots the first to circle the globe by air. The first successful aerial circumnavigation would be a badge of honor, not only as proof of a nation's ability to train fit pilots but also in its ability to construct a plane durable enough to withstand icy cold and tropic heat.

America's involvement in the endeavor was born from the mind of an unflinchingly focused man, Gen. Mason Patrick, the chief of the Army Air Service. "Authority is requested," Patrick wrote in 1923, "to send a flight of four Army airplanes around the world . . . to secure for the United States, the birthplace of aeronautics, the honor of being the first country to encircle the world entirely by air travel."

The war-fatigued nation reluctantly accepted, though other countries with more robust air forces were well into planning their flights. To be the first, Patrick had to move quickly. He coordinated with the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, diplomatic corps, and even the Bureau of Fisheries to ensure the flight's success. The Navy and diplomatic corps, in particular, had enormous roles to play.

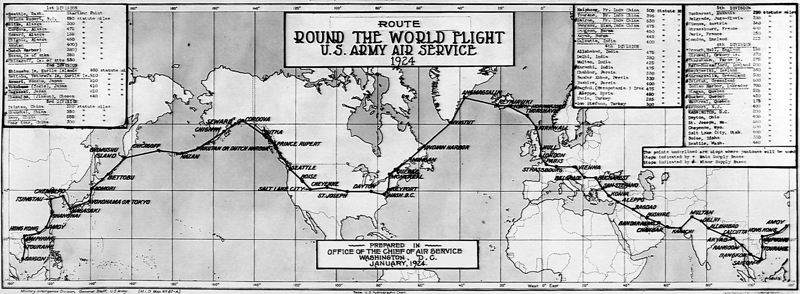

Each leg of the flight would be less than a thousand miles so the pilots could service their planes and rest. Around the entire globe, airfields had to be scouted out or water landings planned, sometimes in areas where the locals had never seen planes or heard of their existence. Where airfields did not exist, the Navy would provide ships for safety and logistic support for water landings. The diplomatic corps had to obtain permission from 22 separate countries. The recent revolution in the Soviet Union hampered planning because the United States did not recognize the new government there, and so the route was adjusted south over the lower parts of Asia.

Such logistic considerations quickly made the world flight one of the largest peacetime military operations in history, and all from a military that was entirely unprepared. It was 1924, and World War I, thought to be the War to End All Wars, had made a large standing military unnecessary. The military industry was so atrophied that an American-made plane capable of making the flight did not even exist.

The task of designing an American aircraft for such a flight fell to Donald Douglas, a young aircraft designer, and his engineer, Jack Northrup. What emerged from the hangar of his Douglas Aircraft Company 45 days later was a 38-foot-long, open-cockpit biplane armed with a 450-horsepower, 12-cylinder Liberty engine. Four Douglas World Cruisers were built for the trip—the Seattle, Chicago, Boston, and New Orleans—and, as it was Prohibition, each was christened with the "spirit of the times," water bottled from a source near each of the plane's namesakes.

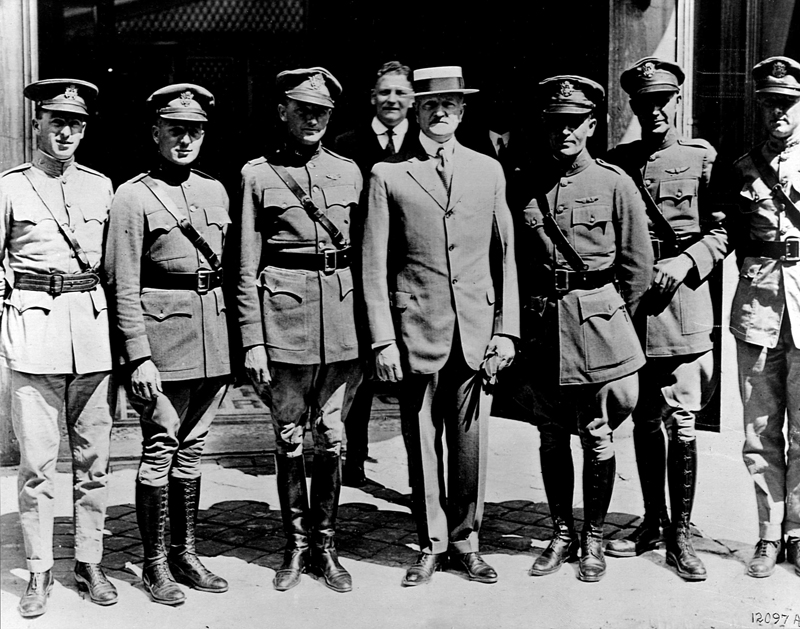

General Patrick hand-picked four pilots for the journey: Maj. Fredrick Martin would fly the Seattle, 1st Lt. Lowell Smith would fly the Chicago, 1st Lt. Leigh Wade would fly the Boston, and 1st Lt. Erik Nelson would pilot the New Orleans. All were relatively young pilots who had proved themselves in the air in one regard or another and, after a six-week course at Langley Field in Hampton, Virginia, were deemed fit to circle the globe.

Nearly a month before the scheduled flight date, they were ready. The diplomatic corps had obtained permission from countries around the world. The Navy was positioned to support the fliers across three oceans and five seas. The fliers were ready, their mechanics chosen, and the planes sat ready in the waters of Lake Washington in Seattle.

On April 4, 1924, the scheduled departure date, the lake was covered in fog, and the flight was delayed. By the next morning, the weather had cleared. With hundreds of spectators lining the shore, Major Martin sped his flagship plane, Seattle, down along the calm lake waters only to smash his propeller, cut a hole in the side of his plane and damage one of his pontoons. The flight was delayed a second time.

Americans across the country were anxious to prove the nation's worth in the realm of flight. They followed any success or failure on the newswires. Despite the country's optimism, aviation was a young profession, and there was uncertainty whether the men or machines existed to endure such an undertaking. The false starts only confirmed their fears. "The betting in Seattle," Arnold wrote in his diary, "is that not more than one plane will get around."

On April 6, the weather was clear. The fliers awoke two hours before dawn and worked over their planes. As the sun rose, so came the crowds for a third day to bear witness to either the start of a triumphant journey or the opening act of a tragic endeavor.

The pilots taxied out from Sandpoint Flying Field and turned to make their approach on the waters of Lake Washington. The months of preparation and well-wishing from officials was over, and it had all come down to this. One-by-one, the planes sped down the lake. First the Seattle, then the Chicago, New Orleans, and Boston. Their heavy pontoons skimmed across the water. As the engines revved, the pontoons lifted off from the water, and finally they were airborne.

From Seattle, the airmen would fly a westerly route. Except Italy, nearly every other nation planning the pursuit had decided that an easterly route provided the best odds to circumnavigate the globe by air.

By going east, the northernmost part of the trip from Japan to Alaska was left until late summer, when the conditions would be more ideal.

Making the trip west in early spring was considered suicide. It meant facing the cold of an Alaska spring and fighting against the trade winds over long stretches of open ocean.

The Americans hedged their bets. If timed correctly, a westerly route would avoid typhoon season in Japan and China, monsoon season in India and Burma, and send them across the north Atlantic before winter. And perhaps, as an added calculation, a westerly route might put the fliers in Paris for Bastille Day, if they made it there at all.

Alaska proved unforgiving. Frozen gusts of wind called "williwaws" shot down from towering mountain peaks and tossed the planes like driftwood. Piloting the open-cockpit Douglas World Cruisers through the northern squalls required a tolerance for pain and a pilot's intuition since charting by compass was nearly impossible in the frigid weather. At night, the airmen woke up every few hours to break ice off their planes. It was Alaska's worst weather in a decade.

Then came Martin's crash.

The world waited for news of Martin and Harvey. Loring Pickering, general manager of the North American Newspaper Alliance, offered a "$1,000 reward to the person or persons first to reach either MAJ Frederick L. Martin or Sergeant Alva L Harvey or their airplane Seattle." But by May 2, with no word from the major in eight days, Lieutenant Smith received a telegram from General Patrick:

Lieut. Lowell Smith, command World Flight.

Don't delay longer waiting for Major Martin. See that everything possible done to find him. Planes two, three, and four to proceed to Japan at earliest possible moment.

Only a few paces into their marathon journey, they had lost their commander and their flagship plane. As the ranking officer among a crew of lieutenants and sergeants, command fell to Smith, pilot of the Chicago.

Lowell H. Smith

An oil man, auto mechanic, and college student, it wasn't until 1915 that Smith, a notoriously shy man, discovered his passion for flying. Having moved to Mexico to join Pancho Villa's army in the struggle for Mexican independence, the bandit general put Smith's skills as a mechanic to use and made Smith the engineering officer for Villa's entire air force—three planes in total. Not long after his arrival, though, Villa's fleet was destroyed: the first plane crashed into an adobe hut, the second was riddled with bullets, and the third nosedived into the ground. Smith was suddenly without a job, but he had found his calling.

No sooner had America entered the First World War than Smith joined the Air Service. He was assigned to be an instructor in Kelly Field, Texas, and a handful of his students went on to become "aces" in a war of which Smith would only see the closing act.

Armistice was only the beginning of Smith's flight career, though. In 1923 he broke 16 records for military aircraft in speed, endurance, and distance by staying airborne 37 hours and 15 minutes at an average speed of 88.5 miles an hour, covering enough ground to cross the Atlantic twice. He pioneered the first aerial refueling of a plane, climbing out onto the plane's wing midflight to attach the gas line to his aircraft. He served on an aerial fire patrol in the Northwest and covered swaths of forest where no plane could land in an emergency. He was the first to fly nonstop from Canada to Mexico, and on a later mission in Nogales, Mexico, he achieved near-legendary status by locating a small hut 110 miles into the desert using only his sixth sense to guide him. It was that same intuition that made him an ideal officer to lead America's airmen around the world.

Japan

On May 15, the pilots left Attu, Alaska, for the 870-mile flight to a small town in Japan called Paramushiru, where reporters and sailors waited to announce the first successful crossing of the Pacific by plane. The only other landing area in the cold barren sea was a small string of islands called the Komandorskis and controlled by the Soviets, who were on such poor political terms with the United States that no arrangements had been made.

The men set off in freezing temperatures for Japan from the small outpost of Attu. By noon they passed over the last stretch of American soil and were flying above one of the most treacherous stretches of water in the world, where the frigid Bering Sea clashes with the Pacific. Black storm clouds appeared on the horizon and barricaded their flight path. Smith could either direct the fliers through the storm or head for Russian waters.

The choice for Smith was easy. Better to risk a political storm than one made by Mother Nature. He aimed for Copper Island, a one-mile-wide break of rock more than 270 miles away and inside Russian territory.

The fliers landed outside the village of Nikolski, on Copper Island, where the U.S. Navy ship Eider had positioned herself after being signaled by the pilots that they had changed course. Not long after, a boat put out from shore with five men aboard, two of whom were in uniform and all of whom were thoroughly, and understandably, confused: this was the first time in history a plane had ever crossed the Pacific, and no one had told them about it.

The Russians asked the fliers to stay aboard the Eider until they received instructions from their superiors in Moscow. Later that night, the officials sent out vodka as a goodwill gesture to the pilots. When word finally came in from Moscow the next day, the fliers were told they were forbidden from landing and had to leave.

With the weather clear and the planes already prepared for takeoff, Smith and his team happily obliged. A few hours later, they were flying over Cape Shipunski, Japan. They landed in Paramushiru at 11:37 a.m. Icicles dangled from their clothes. It was a miserable flight, but the first of its kind: they had just completed the first aerial crossing of the Pacific in human history.

Congratulations poured in.

Kashiwabara, Paramushiru, Kurile Islands, Japan:

Congratulations. Yours is the honor of being the first to cross the Pacific by air. Through its Army and Navy, our country has the honor of having led in the crossing of both great oceans. The Army has every faith in your ability to add the circumnavigation of the globe to its achievements.

John W. Weeks

Secretary of War

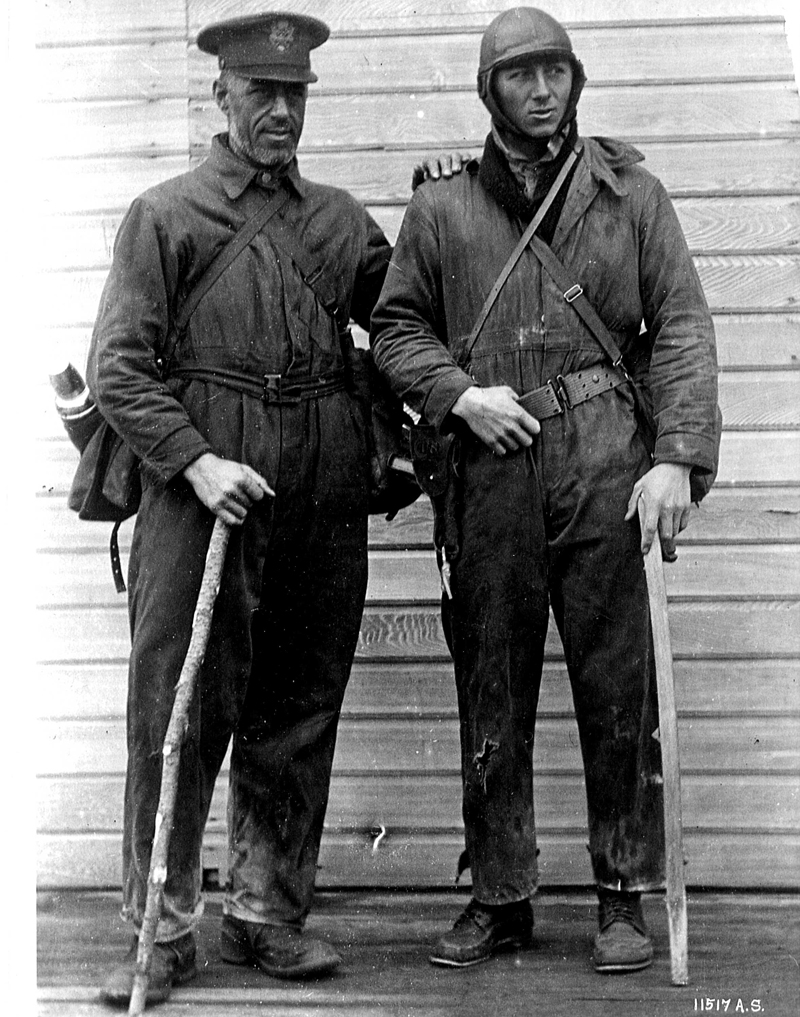

Martin and Harvey

On May 10, Native Alaskan Jake Oroloff saw two figures walking along the remote beach of Moller Bay. It was an uncommon sight—the only people in this frozen part of the Alaskan territory worked in the cannery or lived in the nearby village—and he knew who all of them were.

The men were dressed strangely in thick bundles of clothes. One had a pistol strapped around his waist. The other wore what looked like a pilot's hat on his head. Both were red with burns from the wind and sun.

Oroloff escorted the desperate-looking men to the cannery, where the superintendent and his men appeared as overjoyed to see the strangers as they were to see him. Immediately the superintendent recognized the two downed airmen from the round-the-world-flight. The radio waves had buzzed with news of Martin and Harvey's disappearance, and now the famous fliers were standing in his cannery.

Word of their rescue flashed across the newswires. It was the first sign of life from the two since their crash on April 25. As Martin explained later in his diary, he and Sergeant Harvey had crashed into a mountainside in the fog between Chignik and Dutch Harbor after becoming disoriented. Both survived the crash with only minor wounds but were lost in the remote Alaskan wilderness.

The first and second night they burned parts of their plane to stay warm, smoked tobacco, and alternated sleeping. The thick fog that had caused their crash now inhibited their rescue. By the third day, with no sign of the weather lifting and mindful of the risk of stumbling off a precipice in the fog, they started walking. Taking doses of their emergency liquid rations for energy—two tablespoons constituted a meal—they made their way down the mountain following a creek bed until, on May 6, they finally reached the ocean shore. Along the bay, they found an unoccupied cabin filled with hotcakes and other food. They recovered their strength and rested their eyes—both were heavily affected by snow blindness—and reconnoitered their position. On the tenth, they set out again. Later that afternoon, they were rescued.

For General Patrick, news of Martin's rescue meant the major could reassume command of the flight. The only question was how to catch the fast-moving crew. Patrick's plan was to send Martin eastward to intercept the flight, but the plan was never executed.

For Martin and Harvey, their lives had been saved, but the race was over.

Asia

The greetings the remaining six airmen received in Asia were each more grandiose than the last. For flyboys more interested in aerodynamics than diplomacy, what happened after landing was often the most difficult part of the day.

Lieutenant Arnold, Smith's mechanic, was the unofficial speaker for the group. When Smith, a quiet and shy man, was asked to talk, he would say a few words and defer to Arnold, who was as comfortable behind a podium as he was behind the controls of his Douglas World Cruiser.

Arnold had sold pianos and tobacco before signing up for the war in 1917. After the Armistice, he stayed in the Army and was ordered to fly exhibitions at county fairs to stir up interest in the service. On one occasion he flew straight off a cliff and into a chicken coup. He telegraphed for another plane and was back in the air the next day.

This same tenacity proved effective in assuaging crowds from Tokyo to Constantinople. At times there were 40,000 people waiting for the fliers to land. In Kagoshima, 20,000 Japanese children lined up along the shore sang "My Country 'Tis of Thee" as the fliers landed. In Shanghai so many junks and sampans filled the Yangtze that the New Orleans had to swerve around the river craft on takeoff.

But it wasn't until Indochina that Arnold's social graces were put to the test. Over the jungle country, on the leg between Haiphong and Saigon, the Chicago's engine started to burn red hot. Something was wrong. First, a connecting rod broke. Next, the crankcase punctured. Smith and Arnold had to land, and so they chose a small lagoon in the vast Asian jungle and set down.

The Boston and New Orleans swooped down and dropped off what water they had, but it was barely enough to last the morning in the swampy June heat. The pilots promised to return for the downed fliers, but no one knew how soon a rescue could be mounted.

Once the Boston and New Orleans departed, Smith and Arnold were alone. The tropical heat was a marked change from the cold air of the Bering Sea they had endured only a few weeks before. It didn't take long to work through their water rations. Thirst set in. Crocodiles circled. The lieutenants knew from the bamboo fishing traps in the lagoon that people had to live nearby, but neither knew if the locals would treat them as guests or intruders.

A dugout canoe launched from shore. A man with worn black teeth and wearing a breechcloth floated toward the plane. He paused, and then untied the plane from the bamboo rod of his fishing trap and moved back. Other boats launched after him, and before the two knew it, their plane crawled with curious locals.

Eventually three missionaries set out from the thick forest. Arnold explained their situation in "Doughboy French." They were downed pilots from America, and they were thirsty. The missionaries took Arnold ashore.

Despite their titles, the missionaries were tough negotiators. The first who arrived on the scene was only interested in buying cigarettes from the airmen, and when they would not oblige, he gruffly paddled away. Now on shore, the missionaries showed him the creek from which they pulled their water, but to Arnold it looked fetid. He knew from his training in Virginia that waterborne diseases could easily end the trip and searched for something else for him and Smith to drink. At the makeshift chapel he found a suitable drink, the communion wine, something the missionaries were reluctant to part with.

Arnold searched his wallet for something to bargain with. All he had was a solitary 50-dollar bill—about 600 dollars in today’s currency—but he was desperate and made the offer. The missionaries agreed, and Arnold hurried back to the Chicago to give the wine to Smith, who had been out in the sun protecting the plane from locals. But it was too late, Smith had already turned desperate and drunk from the lagoon. Days later, he contracted dysentery.

Lieutenant Nelson in the New Orleans had no less trouble getting back to Smith and Arnold. After landing in Tourane in French Indochina, he immediately sent out a rescue crew to locate the Chicago. The team asked local missionaries for any news of airplanes, and word came back from a native fishing crew that they had seen two "monsters" flying in the air earlier in the day. Using their bearings, Nelson knew he had found their flight path.

By nightfall, the team was reunited, and the next day canoes were pulling the Chicago past elephants and tigers and toward civilization. Soon after, the Chicago, Boston, and New Orleans pressed on.

India

In Calcutta, with sacred bulls shading under the wings of their crafts, the fliers exchanged the heavy pontoons for wheels and mingled with the British troops stationed there.

After a long day of flying from Calcutta, the Boston touched down in Allahabad. Wade and Sgt. Henry Ogden stepped off the plane. They wiped the sweat from their brows and did their best to hide from the unbearable sun. They were reluctant to service the plane, add oil, and check the engine before another night of glad-handing with government officials and little sleep.

They settled into the task of servicing the plane when they heard an unfamiliar noise. After 10,000 miles they knew every sound the machine made and what it meant, except for this.

It sounded like struggling. It was coming from the baggage compartment. The baggage door swung open, and a familiar sweating man popped out from inside the compartment. He waved.

It was Linton Wells, an Associated Press reporter who had followed the boys from Japan. When the fliers switched from pontoons to wheels in Calcutta, Wells explained, they shaved hundreds of pounds off their weight and so he knew the World Cruisers could support the weight of another man, even if there was no seat for him. So he sneaked aboard.

The fliers were as delighted as they were surprised: Wells was a passionate reporter and had endeared himself to them as a constant companion across much of Asia. In India, Wells was supposed to hand over reporting of the world flight to another Associated Press reporter but was too interested in the flight to give it up. So, with a toothbrush and pencil, he stowed himself away in the Boston. Smith cabled General Patrick to see if the reporter could tag along the rest of the flight but received no word back. Smith gave Wells the OK, and the crew pushed onto Karachi.

Nelson and Harding

An hour outside the booming Indian town, the engine in the New Orleans poured white smoke. Soon oil spilled out its sides. The ground below was cracked desert floor, and any landing would wreck the plane. For pilot Erik Nelson, a crashed landing meant the end of the world flight.

Nelson had circumnavigated the world before. Twice, in fact. Like the rest of the round-the-world team, Nelson's proclivity for school was slight, and his desire for adventure strong. By the time he was 16 he had found his calling on the open sea. A Swede by birth, Nelson first worked as a hand on a barque with a Swedish crew. While cruising the waters of Uruguay, Russia, and the United States, he taught himself English. Soon he was on British boats. By 1909, hearing that deckhands on American racing yachts were well paid, he made his way to Hoboken, New Jersey, and toward American citizenship. By 1917 Nelson had tried to enlist in the Esquadrille Lafayette and twice in the U.S. Army Air Service before he was accepted. By 1919 he was setting records on flights across the Grand Canyon and from New York to Nome, Alaska. He was not a man to give up easily.

His mechanic was just as resilient. Second Lt. Jack Harding hadn’t circumnavigated the globe, but he had circumnavigated the continental United States by air on the 1919 "Round-the-Rim-Flight." Harding first impressed another world flier, Les Arnold, on an earlier flight when he climbed out over the engine and made midair repairs to the machine so they would not have to land.

Now here Nelson and Harding were, more than 12,500 miles from Seattle, halfway around the world over India, and their hopes of circling the globe by air were dissolving in front of them.

One of the engine's pistons snapped. Two other cylinders broke apart. The plane’s exhaust springs shot out through the exhaust stacks. The engine was literally falling apart as the two inched on to Karachi. One of the pieces grazed Harding's temple. The motor stopped dead. Then restarted. Hot oil poured out of the engine block and onto Nelson. Every few minutes he wiped his goggles off with a cheesecloth so he could see. For 75 miles Nelson dropped the plane 500 feet or so to keep the engine from overheating and then rose back up to dip again, barely keeping the machine alive.

Then, Karachi.

When Nelson and Harding landed, they had lost more than 11 gallons of oil, more than a third of what the cruiser carried. A crowd was there to see the plane limp in, black muck dripping off everything from its pilots to the New Orleans's rudder. It was the Fourth of July.

One of the men in the crowd, the American consul, handed Smith a telegram from General Patrick. It was regarding Wells, who had already flown in the Boston's tiny baggage compartment for more than 1,700 miles. "Request disapproved," it read.

Paris

From Baghdad to Constantinople the fliers traversed land marked with the ravages of war. All were ancient sites worthy of a lifetime of exploration—Persia, Iraq, Syria—but Smith allowed no time in their schedule for undue delays. They all had their eye on Paris and were determined to make it there by Bastille Day.

They touched down on July 14 at Le Bourget Aerodome, the same stretch of land where, three years later, Charles Lindbergh would land the Spirit of St Louis. Throngs of Frenchmen and Americans cheered their arrival. Gen. "Blackjack" John Pershing greeted them as did the French president, who escorted them to the ongoing Olympic games. Less than seven years earlier, Nelson and Wade had fought against the Richthofen's Flying Circus over this same land. Arriving in Paris had a sense of homecoming for the both of them, they wrote.

Above Bastille Day, the Olympics, and their arrival to familiar lands, the pilots had something else to celebrate: the fliers had set a new speed record between Tokyo and Paris, blasting past the old record by two full days. But with news of the progress of the other world flights—Britain and Italy were both gaining ground—the team had to press onward, next across the English Channel and up to the scuttled German fleets at Scapa Flow.

The fliers prepared to cross the cold northern Atlantic. They switched from wheels back to pontoons in England and waited for the Navy ships to position themselves. For 13 days the fliers waited for the appropriate conditions and for the logistical support necessary to traverse the dangerous waters. Then they were off.

Leigh Wade

Leigh Wade, pilot for the Boston, was one of the youngest airmen on the flight. Born in 1897 in Michigan, Wade found his way into the Army through the North Dakota National Guard. It was with this same outfit that he went down to Mexico in 1916 to defend the border from raids by Pancho Villa, the same outlaw-general Lowell Smith was serving.

In World War I, Wade was tapped to be one of the first two airmen to introduce aerial acrobatic maneuvers to service pilots, from vertical banks to loops and nosedives. Like most of the pilots, the Great War was only the beginning of a great flying career for Wade, who in his service would reach the rank of major general and share the pilot's seat with aviator luminaries like Amelia Earhart.

After the Armistice, Wade set the record for the highest-altitude flight in 1919 by reaching 27,120 feet as a test pilot, an extraordinary height considering it was an open-cockpit plane. By author and later noted radio newscaster Lowell Thomas's count, Wade, as a test pilot, calmly and successfully landed at least two planes that were on fire.

In the cold stretch of fog between England and Iceland, he would land a third broken plane.

The Atlantic

After nearly two weeks of delays, the pilots were flying again. On their first trans-Atlantic journey, thick fog separated the crew of the New Orleans from the Boston and Chicago. As Nelson told it, the fog was so bad that he could only see six inches in front of him. Soon he was caught in the wash of one of the other planes, lost control of his own aircraft, and went tumbling down.

Separated and worried for their partner plane, the Chicago and Boston returned to England. It wasn't until they arrived that they learned the New Orleans crew was all right and had carried on to Hornafjord, Iceland, where they would wait for the other planes.

Over the same stretch of water the next day, Wade's craft began hemorrhaging oil. There was nothing to do. Wade landed the Boston in the desolate waters. He signaled the Chicago not to land due to the heavy wash of the sea, and so Smith and Arnold circled the Boston and then flew for help.

Some hundred miles off, they dropped a letter at a village telling of the downed aircraft and then shot toward the nearest Navy destroyer, Billingsby. Without a place to land and with no radio, Arnold would have to drop a note on the ship's deck explaining what had happened to the Boston. He only had two notes, and if he missed his mark, there was no telling how long it might take to mount a rescue. The ship was traveling nearly 20 knots. Calculating the right time to drop the message to the deckhands below was impossible. Smith circled. Arnold aimed and dropped the first message. It missed. He tied the second message to his own life preserver, aimed, and dropped the last and final note they had explaining the whereabouts of the Boston. It missed, too.

Understanding the panic of the pilots above, one of the Billingsby sailors dived into the frigid waters and retrieved the message. The captain read it immediately and signaled that he understood with three blasts of the whistle. The crew radioed nearby ships of the emergency landing, including the Richmond, and then set off to find the fliers. The Billingsby shot off in such hot pursuit of the flier's coordinates that she burned the paint right off her smokestacks, according to Thomas.

Hours later, adrift in the cold ocean, a trawler had spotted flares shooting up from the downed plane.

"Do you want any help?" the skipper yelled.

"Well, I should say we do!" Wade replied, flummoxed at the question.

As the trawler unsuccessfully attempted to tow the Boston to land, the Navy cruiser Richmond arrived. The sea rolled tremendously, and as the crew attempted to move the World Cruiser, one of the wings dipped under a wave and popped like a fragile bone. Still, with the Richmond there, they could hoist the damaged plane onto its decks, return to Kirkwall, and finish the flight after some repairs.

But in the heavy sea, the tackle was wrenched loose from the main mast and the plane crashed into the water, destroying the Boston's pontoons. A second attempt was made to hoist the plane on board, but the weather grew too violent to hoist the plane. The only hope now was to tow the Boston in, and so the Richmond made a straight line for land.

All night long they worked toward the coast, and all night long the crew watched their plane, expecting the worse. Exhausted, and with nothing left to do, the pilots went to sleep. A mile off shore, just after 5 a.m. they were awakened.

The Boston had capsized. They were out of the race.

They had been traveling for five months and covered nearly 20,000 miles of land, sea, and air. The round-the-world team had lost half its ships, and now there were only two stretches of water to cross before the remaining fliers reached North America: from Iceland to Greenland, and then across the Atlantic to Labrador.

Only Italy and America had pilots left in the race, and both sets of pilots were in Iceland. Britain's Maj. Stuart MacLaren had left England on March 25 to complete his world flight but had wrecked crossing the Pacific only weeks before. Maj. Sarmento De Beires of Portugal had made it from Lisbon to Macao, but his plane had become stranded after landing in a cemetery. With the Boston gone, only three air ships—the Chicago, New Orleans, and Italian pilot Antonio Locatelli's Dornier-Wal—were in the running to be the first around the globe.

On August 21, accepting an invitation to fly with the Americans so the Italian could benefit from the protection of the U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers, Locatelli, Smith, and Nelson departed the island country together. Locatelli did his best to stay with the slower Douglas World Cruisers, but soon the Italian had shot off ahead of the Chicago and New Orleans.

For the first 500 miles, the air was clear enough that the fliers could see that the crew of the Navy ship Billingsby had painted the words "GOOD LUCK" in huge white letters on the deck. But then, about a hundred miles out from Greenland, high winds and fog socked in the fliers. The airmen hovered above the waves to escape the fog, but the weather crawled down with them. Visibility dropped to a hundred feet. As they came closer to land, icebergs appeared. At a speed of 90 miles an hour, turns were made in split seconds. It was dangerous flying. And then what they feared would happen, did. Smith later wrote:

Diving through a small patch of extra heavy fog that was clinging close to the water, we emerged on the other side to find ourselves plunging straight toward a wall of white. The New Orleans was close behind us with that huge berg looming in front. I banked steeply to the right. . . . Both left wings seemed to graze the edge of the berg as we shot past it. And in far less time that it takes to tell it, the two planes were lost from each other.

The Chicago pressed on to Frederiksdal, Greenland, and landed. Forty tense minutes later, out of the fog came the New Orleans. For many of the natives, they were the first planes they had ever seen.

There was no sign of Locatelli. With his faster monoplane the Italian should have arrived first, but he had not. He was missing. News of the downed Italian pilot spread quickly, and soon General Patrick had radioed back instructions for his search:

Authorization granted to exercise every facility and to spare no effort in the search for Locatelli

Eighty hours of search ensued. Given ocean drift and the flight path, the Navy determined Locatelli could be anywhere in an area the size of Maryland. It was the Richmond, the same ship that had lighted on the Boston, that found the downed crew four days later, tired and hungry on the beaten remains of their monoplane, but otherwise all right.

While the world fliers struggled through the fog and icebergs, Locatelli had found the weather too much and put down on the water to wait out the storm. But the water was deceptively rough, and when it came time to take off again, his plane was rollicked by the icy waves.

Now, the hopes of a world flight rested on the shoulders of four young Americans and the wings of two battered planes, the Chicago and the New Orleans.

From a remote beach in Greenland, the crews of the two planes prepared for their final oceanic flight. While the plane engines were relatively new—Douglas Aircraft Company had built 15 Liberty engines for the entire trip—the aircraft themselves had endured more terrain and more travel than any plane of the era. The North American continent was less than 600 miles away, but to circle the globe meant not only reaching North America, but crossing it, too.

The crews of the Chicago and New Orleans set out early in the morning. The New Orleans took off with few issues. The Chicago was less fortunate. Water take-offs were a routine problem for the aircraft. The heavy pontoons and the large planes created suction on smooth waters that required an immense amount of horsepower to break. After two hours of false departures, the Chicago finally broke free, and the two planes were airborne for their last open-water leg.

After a few miles of fog interlaced with the same icebergs that had nearly killed them on the flight from Iceland, the weather broke, and it was a rare clear day in the Arctic waters. But as Labrador grew on the western horizon, the fog returned.

As the planes negotiated through the poor weather, the Chicago's engine started to hemorrhage oil. Arnold diagnosed the problem quickly. The fuel pump had malfunctioned. The plane had essentially suffered a heart attack, and the secondary fuel pump would not work either. Arnold immediately took over the task, hand-pumping oil through the engine's veins to keep it airborne. He had to keep the plane's heart beating long enough to reach the protected bays of the remote Canadian wilderness. They were four hours away.

On shore, at a remote outpost called Icy Tickle in Labrador, reporters had waited a month to catch the fliers landing on the opposite side of the continent they had left almost half a year ago. Word had passed that today might be the day.

In the distance, the low roar of the Liberty engines cut through the air, and the reporters clambered up the desolate rocks to sight one of the planes. Then, there they were. First one plane, and then a second close behind.

Movie cameras cranked from ashore and on small skiffs in the bay as the two planes landed. The Chicago was covered from top to tail in murky oil. Lieutenant Arnold had manually pumped the Chicago's engine for four hours. "I pumped until I thought I couldn't pump anymore," Arnold explained. "Then I'd look down at the cold water and start all over again."

On August 31, they touched down on the American continent for the first time in 20,000 miles.

And Home Again

On the final stretch to America, the Chicago was plagued with troubles. After landing at Hawkes Bay, Newfoundland, Arnold discovered that the battery terminal had snapped. By Nova Scotia it was the spreader bar that had broken. The plane was falling apart.

In Pictou Bay, the crews of the three planes were reunited. Lt. Leigh Wade and Sgt. Henry Ogden had been rushed the only other Douglas World Cruiser in the world (Douglas's original prototype), dubbed it the Boston II, and were ready to finish what they started so many miles ago. They would cross into the United States together.

At Boston, namesake of the Boston and the Boston II, the world fliers were greeted by a 21-gun salute and the largest crowd yet since departing nearly half a year earlier. General Patrick escorted the fliers in, and soon enough they were receiving speeches from the governor at the capitol building and parading to their hotel with police escorts.

The pomp and circumstance followed them across the country. On September 5 the fliers had touched down in the United States, but it took another 23 days to make it to Seattle, where, six months and six days after departing, they completed the world flight.

It was not weather or the strained engines that delayed them on the flight across the country but the spectators who were so eager to catch a glimpse of what were called the "Magellans of the sky." In New York it was the Prince of Wales and the state's senator, James Wadsworth, who greeted them. In Washington, DC, at Bolling Field it was President Coolidge himself. He, along with his entire cabinet, had waited more than four hours on a wet autumn day to see the fliers. In Chicago, a larger crowd turned out than anywhere else. By Texas, Smith and Arnold's logs read the "usual reception" was held, clearly tired of the fame they had earned.

In San Diego, one of the debated start points of the trip, 26 escort planes landed alongside the three world cruisers. 35,000 people turned out at the stadium to catch a glimpse of the fliers that night. In Los Angeles, 200,000 spectators gathered at the field and overran the police guards. Smith wrote that it was impossible to refuel the planes owing to the crowd, so they were delayed there an extra day.

At 1:28 p.m. on September 28, the fliers landed in Seattle wingtip to wingtip so that none would know who landed first.

Seventy-six flights in 66 days had taken them the 26,345 miles around the world. Overall, 175 days had passed since their departure, the balance spent grounded making repairs or waiting for clear weather. According to General Patrick, the flight had cost $177,481.35—about 2 million dollars in today's currency—a small price that launched four men around the world and into history.

The airmen had accomplished a feat that no other country had achieved before or since, save one other American pilot in 2000 who circled the globe in a single-engine, open-cockpit plane like the fliers who made the trip over 75 years earlier.

The airmen of the world flight operated on the will of a nation and the youthful gut of aeronautics to accomplish what General Patrick called the "greatest achievement in [the] history of aviation."

Note on Sources

Certainly the most comprehensive work on the First World Flight is Lowell Thomas's The First World Flight (1925). The book is largely a narrative compiled from the diaries and interviews of the pilots and mechanics and includes maps and rare photographs of the flight. It is currently out of print.

A handful of websites tell the story of the First World Flight and have some wonderful pictures and separate accounts of the journey.

- National Museum of the Air Force: This site provides a day-by-day account of the flight as excerpted from the pilot's diaries or newspaper reports at the time. It is a very detailed account for those looking to dig deeper into the flight's details.

- Seattle World Cruiser Aerodrome: This is a great forum for persons interested in the historic flight.

- U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: This site has an essay ("Around the World in 175 Days") primarily focusing on the development of the Douglas World Cruisers by Douglas and Northrup.

Also of particular assistance was the staff at Air Force Historical Society Office at Bolling Airfield in Washington, DC. The Air Service Newsletters there (available over e-mail) provide detailed accounts of Major Martin's crash and a few other details regarding the Atlantic leg of the trip, in particular between Iceland and the flight's arrival in Boston.

The National Archives contains a tremendous amount of information on the flight.

- Record Group 18, Records of the Army Air Forces, Central Decimal File, 1917–1938, decimal #373, boxes 727–729, holds the correspondence of the Army Air Service relating to the flight. Various telegrams, congratulatory letters following the flight, and financial details are all in this section.

- Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State, Central Decimal File 1910–1963 (1910–1929 segment), decimal #811.2300, boxes 7483–7484, contains the files pertaining to the diplomatic arrangements for the flight. The two boxes hold correspondence, mostly dealing with preparatory arrangements and little to do with the actual flight itself. Box 7484 contains photographs as well.

- Record Group 342, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, 342-FH, videodisc #3B-07833 to 08216, contains the photographs of the flight. There are a few glass negatives outside of this section, but most of the images are housed here.

- Record Group 342, Records of U.S. Air Force Commands, 342-USAF 17686, also has motion pictures of the flight, which is available on the National Archives YouTube site

The National Air and Space Archives of the Smithsonian Institution created a finding aid for the National Archives holdings relating to the flight. As a word of caution, many of the documents listed in the finding aid are split between the Washington, DC, and College Park, Maryland, facility.

The Chicago is on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.