Children as Topic No. 1

White House Conferences Focused on Youths and Societal Changes in Postwar America

Summer 2010, Vol. 42, No. 2

By Marilyn Irvin Holt

© 2010 by Marilyn Irvin Holt

Between 1946 and 1960, 59.4 million children were born in the United States. They learned to read with Dick and Jane or with Jack and Janet. They, as well as the teenagers who were children during World War II, often attended schools that were overcrowded. They were told to "duck and cover" in the event of a nuclear attack, and for an increasing number, family mobility meant growing up in the suburbs. This was the first television generation.

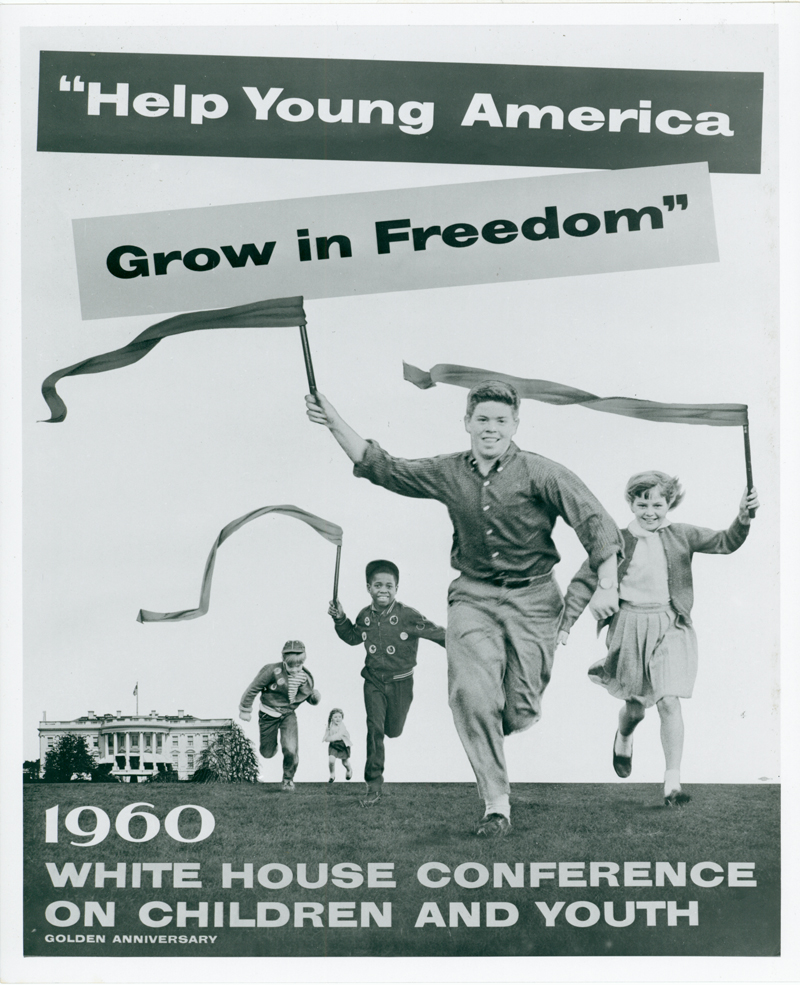

Against this backdrop of the baby boom and a culture that increasingly regarded teenagers as consumers rather than economic contributors, the 1950 and 1960 White House Conferences on Children and Youth examined the state of American childhood and adolescence in postwar America.

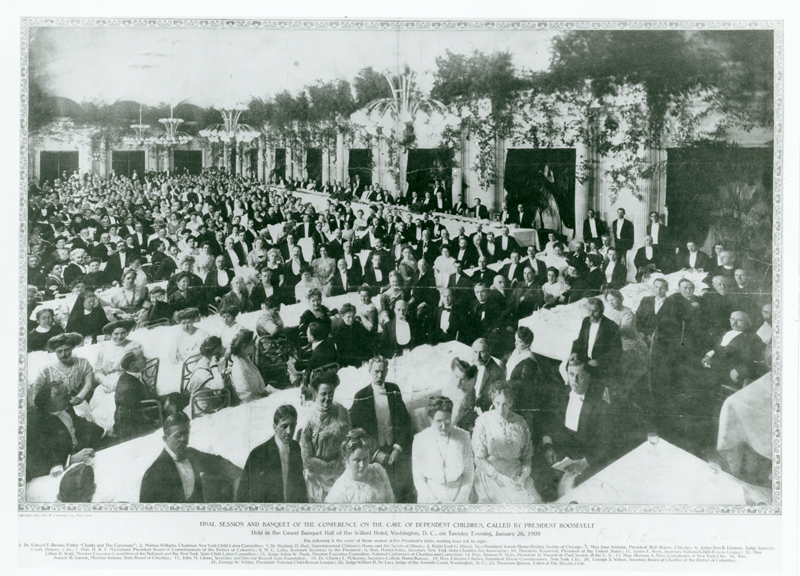

The concept of holding conferences targeting child-related issues was not new. The Midcentury Conference of 1950 and the Golden Anniversary Conference of 1960 continued a tradition that began in 1909 when President Theodore Roosevelt, urged on by activists and reformers in the national child welfare movement, sponsored the first White House Conference on Children and Youth.

Some child-related issues such as care for dependent children appeared on the agendas of every White House Conference on Children and Youth, but many topics represented trends of an era and immediate changes occurring in America. This was especially true for the postwar years, when conferences were influenced by the need for family housing and more schools, the sudden influence of television, and the social shifts created by the civil rights movement.

Themed "Care of Dependent Children," the 1909 conference endorsed a number of recommendations for promoting the health and welfare of young laborers, the orphaned, and the children of impoverished parents.

It was the Progressive Era. Reformers wanted more government regulation, rather than less. They called for federal legislation dealing with such issues as controlling child labor, but one of the most important demands of the conference was formation of a federal bureau devoted to issues directly related to children. That goal was accomplished when the U.S. Children's Bureau was established in 1912 under the Department of Labor. And, intended or not, the 1909 conference laid the foundation for future conferences. The next occurred in 1919. Others followed on the decimal year. The last was held in 1970.

It was President Herbert Hoover who shaped the framework for all future conferences. There was a fundamental shift from the previous concentration on welfare standards and dependent children to an agenda that addressed the rights of children, including the right to medical care and education. Although the 1930 conference discussed earlier conference topics of dependent children and their needs, the meeting put more issues on the table and considered all children.

Hoover established the practice of providing government funds; the 1930 conference was financed with a grant from money raised, but never used, for post–World War I European relief. He also set the precedent for a pre-conference planning committee. The committee set the overall theme (the Hoover conference was entitled "Child Health and Protection"); worked with the U.S. Children's Bureau, state, and local organizations; decided who would be invited; and dealt with the nuts and bolts of meeting arrangements.

White House Conferences expanded in participation and content with each meeting. This is apparent in the 1950 and 1960 conferences, which offer a window to the impact of the war years and to what often seemed overwhelming demands of the baby boom of the 1950s.

Many topics, such as juvenile delinquency and foster care, had been discussed since the first White House Conference in 1909, but the context in which they, and newer subjects, were viewed took on added relevance and urgency by the mid-1900s.

To some degree, conferences focused on righting problems that were "typical of the decade." At the 1950 conference, for instance, little attention was given to the quality of television programs or the medium's impact on children. There were, after all, fewer than 100 commercial television stations in the country. Nor did meeting delegates fully understand, or appreciate, postwar population shifts to the suburbs or to states that "boomed" with employment opportunities in defense industries.

By 1960, however, both television and the demands of changing population patterns were widely discussed in forums that ranged from the topics of social services to education.

The 1950 and 1960 conferences received information from the Interdepartmental Committee, which was made up of federal agencies and departments that administered programs that in some way affected children. Established in 1948 to reduce duplication of services and to promote better communication within the government, the committee had 28 members by the mid-1950s. The statistical data and analysis collected and disseminated by the committee was an important resource for those planning and later attending the White House conferences. Where else would conference attendees learn that the National School Lunch Program fed 9 million children during the 1950–1951 school year? And how many would have known, unless familiar with the program, that over 155,000 war orphans (children of servicemen killed in World War II and Korea) were eligible for aid through the War Orphans Educational Assistance Act?

It would be impossible here to treat each topic in depth, but a small sample provides some idea of what concerned the general public and policy makers of mid-20th-century America. Included here for consideration are civil rights/integration; juvenile delinquency; adoption; foster care; housing; and the Cold War shadow of communism.

Perhaps the most socially charged issue of the postwar era was civil rights. The discussion was not new. The final report of the 1940 conference, for instance, devoted a chapter to the extent that minority children (not only African American, but Filipino, Mexican, Japanese, Chinese, and Native American) were deprived of social services and schooling.

In 1950, the status of minority children remained an issue, but the focus was on those of African American heritage. Studies of Aid to Dependent Children programs offered a case in point. In southern states, discriminatory practices kept many African American children from receiving support through ADC programs, and when money was provided, it was far less than that available to children in other sections of the country. In Mississippi, for example, the state legislature refused to increase funds for ADC. The average grant to a child was 6 dollars a month; by comparison, the monthly payment in Illinois was just over 26 dollars.

These disparities were discussed at the 1950 conference, but the overall conversation on minorities was reconfigured by civil rights and integration. The issues were hotly contested among states submitting reports and those attending the national conference. (The report from President Harry S. Truman's home state of Missouri was among those that called for an end to segregation, because it produced "psychological insecurity" in children.)

Conference participants found it difficult, if not impossible, to reach common ground. On the one hand, recommendations that the 1950 conference support integration were voted down, as was the demand from a bloc of younger delegates and the American Psychological Association that no future meetings or conferences be held in Washington, D.C., until the city integrated its restaurants and hotels. On the other hand, the Midcentury Conference's "Pledge to Children" stated: "We will work to rid ourselves of prejudice and discrimination, so that together we may achieve a truly democratic society."

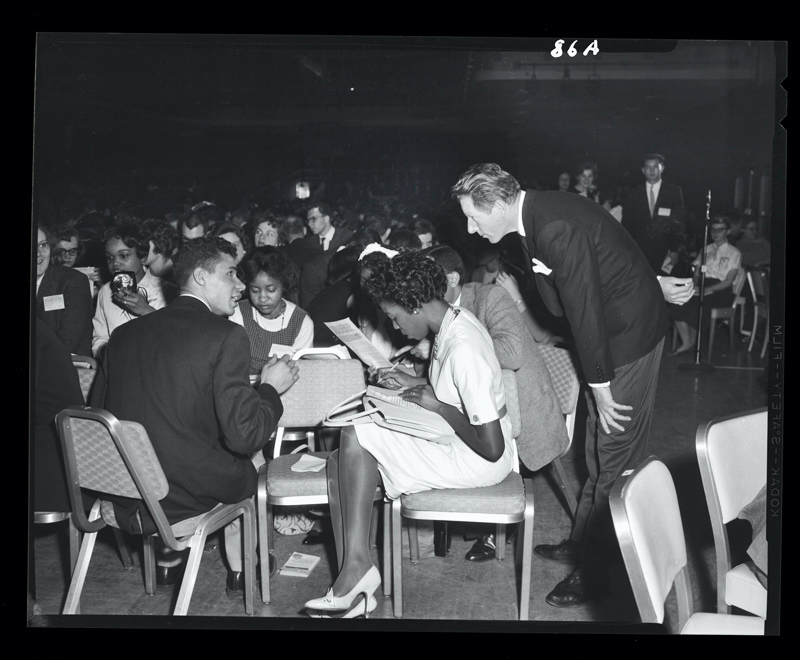

Between 1950 and 1960, public facilities in the District of Columbia were integrated; the Supreme Court ruled "separate but equal" unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education; and federal troops escorted black students into Little Rock's Central High.

Certainly, discrimination and racial tensions were far from eliminated during the fifties, but when the Golden Anniversary Conference convened in 1960, attitudes were perceptively different. There was little opposition to resolutions that called for an end to segregation in schools, housing, and employment. More than half of the workgroups demanded an end to discrimination, and a number voted to support "current" sit-ins at lunch counters. To make the point, a number of "aggressively progressive" youth delegates, noted Ben Furman in an April 2, 1960, New York Times article, spent their free time organizing picket lines to show support for these sit-ins.

Another topic of concern was juvenile delinquency. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke at the opening ceremonies of the 1960 conference, he specifically mentioned it as a problem deserving immediate attention. The President referred to delinquency as a "world wide" problem. (In fact, most industrialized countries grappled with youth gang activity, and not even harsh tactics employed by authorities in the Soviet Union could entirely curb "tough gangs that often terrorize people on the streets.")

The time-honored response to delinquency was incarceration. In the 19th century, a few private charities tried intervention as a means of redirecting the paths of potential juvenile delinquents, but it was not until the end of the 1800s and the early 1900s that more effort went into "saving" youngsters through preventive measures such as organized sports and activities offered in urban settlement houses.

Delinquency and its prevention was a topic at the 1909 White House conference, but the public generally regarded delinquency as something confined to urban areas and the lower socioeconomic classes. The issue was largely ignored by most Americans until it became a problem of the middle class.

In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, juvenile delinquency found middle America. The popular press and Hollywood fueled the public's fear that delinquency lurked around every corner—and in better neighborhoods. Articles in national magazines carried such titles as "Child Criminals Are My Job," "Juvenile Crime: Is Your Boy Safe?," and "Delinquency: Big and Bad."

A spate of "delinquent" movies also appeared. Many were low-budget B movies, but that could not be said of two of the most well-known films of the period. The Blackboard Jungle (1955) brought a frightening realism to the subject of urban delinquency, and Rebel Without a Cause (1955) made audiences uncomfortable with its white, suburban characters who lived in a "nice" town.

That was becoming the reality, said the Children's Bureau in the opening statement for a 1954 conference on juvenile delinquency. Juvenile delinquency was on the rise "in more fortunate neighborhoods and homes," and the sharpest increases over the national average were being seen in small cities and towns.

One of the Children's Bureau mandates was to focus on minors who came before juvenile courts, to conduct field studies, and to maintain nationwide statistics. The bureau reported that the number of young people brought before judges more than doubled between 1948 and 1956, with 1954 showing an "an all-time high."

The spike that occurred during the war years, when latchkey kids and unsupervised teenagers contributed to high delinquency figures, should have dropped with the return of peace and "normalcy." Instead, they rose. Social commentators, community leaders, law enforcement experts, and welfare workers felt that there was plenty of blame to spread around—parents, television, movies, rock and roll, bad neighborhoods, gangs, inadequate teachers, lack of community leadership.

To this, the federal government added another factor that had been a subculture for decades but now threatened mainstream America—the international trade in narcotics. Eisenhower spoke of the problem in his 1955 State of the Union message and subsequently asked Congress to provide federal aid to states for anti–juvenile delinquency programs.

Despite this background and Eisenhower's request, Congress failed to approve the money in 1955, 1956, and 1960. It was only after the momentum of the 1960 White House Conference that Congress, under the Kennedy administration, authorized federal grants in 1961. The program provided $10 million a year for pilot projects, training programs, and studies by state and local agencies and nonprofit groups to combat delinquency.

The problems of delinquency and its prevention continued with each generation, as did the question of the best treatment for orphaned and dependent children. One answer was adoption.

Between 1944 and 1953, the number of adoption petitions filed in U.S. courts rose from 50,000 to 90,000, and for the remainder of the 1950s, the number of adoptions per year averaged between 90,000 and 95,000.

Just as there were numerous motivations for adopting children, there were variations in the adoptable population. Slightly less than half were adopted by stepparents or relatives, while a large number of those adopted by nonrelatives were the children of unwed mothers.

Youngsters also arrived from overseas. After World War II, orphans were adopted out of western Europe, and both during and after the Korean War, orphans from that conflict were adopted by American families.

The rise in both foreign and domestic adoptions—the Bureau of Indian Affairs even promoted a program for the adoption of Native American children into Caucasian homes—was both heartwarming and disturbing for social welfare organizations.

There was no uniformity from one state to another in adoption laws, and despite years of work by the Children's Bureau and nonprofit organizations, there were policy gaps that did not always protect the adoptive child or parents.

Participants at the 1950 White House conference argued that standards for agencies placing children had to be strengthened, and more than one state report reflected acrimony between welfare workers and physicians who bypassed agencies and arranged private adoptions.

Despite problems cited by the social welfare community, adoption was one option for effectively and humanely providing children with homes. For those not available for adoption but who had no homes or whose home life put them in danger, there was the orphanage or foster care.

If given a choice, welfare workers generally favored foster care over the orphanage. In fact, in its "Pledge to Children," the 1950 White House Conference made no reference to adoption or to orphanages but included foster care in its language: "We will work to conserve and improve family life and, as needed, to provide foster care according to your inherent rights."

In 1949 the Social Security Administration, which provided survivor's benefits through Social Security funds, estimated that there were 100,000 true orphans in the United States (children with no living parent), and three out of every 100 orphans under the age of 18 lived in an institution.

Foster care proponents hoped to reduce the child populations in institutions as well as keep children who were entering the welfare system out of orphanages. In 1949 an estimated 1.5 million children were not living with their parents or with a surviving parent, and the number was certain to increase with the national birth rate.

As might be expected, there were obstacles to finding foster homes. A problem, often heard echoed today, was the "dire shortage" of good foster homes. The same complaints came from around the country. Welfare workers believed that it was difficult to find foster families because more women worked outside the home; many families were "preoccupied" with their own problems; and inadequate housing made it difficult for families to take in a child when the house or apartment was already overcrowded.

A shortage in housing, as well as inadequate conditions in homes and apartments, affected not only the availability of foster care homes but children in general. Overcrowding and substandard housing had the potential to negatively affect children's health. In turn, youngsters did less well in school. There were ripple effects that had long-reaching implications for a child's quality of life. The postwar housing shortage and the need for "radical improvements in existing dwellings" dated back to the depression of the 1930s, when there was little new home construction.

New construction and home modernization were put on hold during World War II, when materials went to the war effort. By the time GIs began to come home, the housing problem could no longer be ignored. The dramatic rise in marriage and birth rates turned the housing crunch into a crisis.

Demands were just as likely to be found in farm communities as in small towns and cities where single-family homes and apartments were often at a premium. Families were forced to live with relatives or share space with other, nonrelated families. (A reported 6 million families were "doubling up" with friends or family in 1947.)

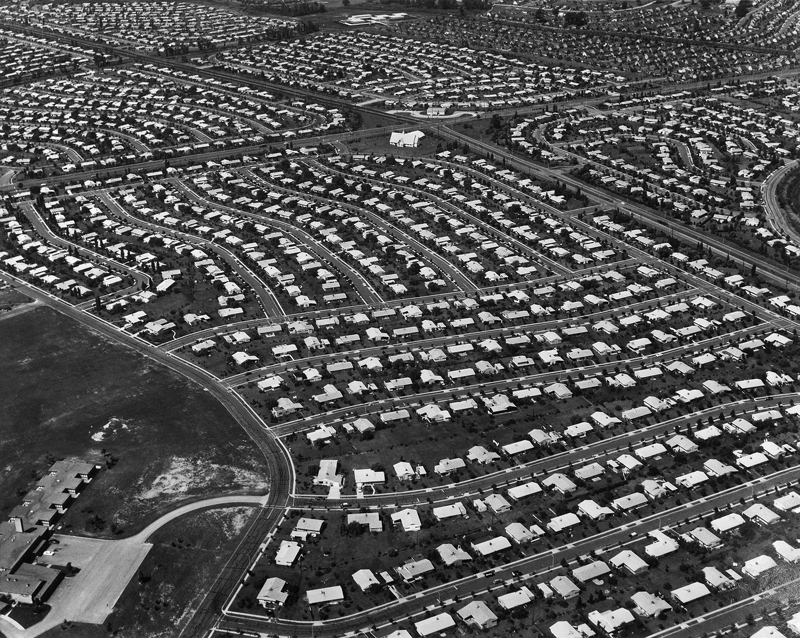

Over time, housing demands were alleviated for the growing middle class. The Veterans Administration program of guaranteed mortgage insurance to returning GIs allowed families to build or buy new homes, and suburbs such as the famous Levittown, New York, became the new communities and towns of the mid-20th century.

While there was a general demand for a national housing program that would meet the needs of families in every income group, in every type of community, delegates at the 1950 Midcentury Conference were most concerned with those at the bottom of the social and economic ladder. They suggested that more than 800,000 low-rent housing units be built "at full speed." Conference participants also endorsed housing legislation that provided for urban redevelopment, slum clearance, and construction of "good quality" low-cost housing.

Construction and urban renewal were already under way as a result of the 1949 Housing Act, but progress was slow. In many communities across the country, local projects met with resistance. In California, for example, 20 out of 30 projects were defeated by anti–public housing campaigns. This meant that the poorest families, often minorities, remained in substandard housing and neighborhoods, taking an emotional and physical toll on children.

The topics of civil rights, integration, juvenile delinquency, adoption, foster care, and housing help illustrate the ways in which discourse and policies were nuanced by public awareness, by government programs (at both the state and federal levels), and by the immediate cultural and political environment.

World events and foreign policy were also influential. The 1940 conference, for example, was held against the backdrop of a decade of national depression and an uncertain future. Much of the world's people lived under military dictatorships, and war was already a reality in Europe and the Far East. Searching for the positive, organizers of the 1940 meeting chose the theme "Children in a Democracy." With all its internal problems and the pressures from abroad, the United States could still say that its children lived in a democratic society.

Democracy was still very much on Americans' minds 10 years later at the 1950 conference. The country had fought a war that defeated Nazism and Fascism, but the United States faced new military threats from Communist countries and what many believed was an insidious infiltration of Communist sympathizers inside the United States.

In 1949 the Soviet Union tested its own atomic bomb. In the same year, Alger Hiss went on trial for lying about his affiliation with a one-time Communist, and in 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy proclaimed that he had a list of Communists working in the U.S. government. When the Midcentury Conference convened, American troops were fighting in Korea. Should conference participants fail to recognize the threat that communism posed to the United States and its children, President Truman offered a reminder at the opening ceremony:

[W]e must remember that the fighting in Korea is but one part of the tremendous struggle of our time—the struggle between freedom and Communist slavery. This struggle engages all our national life, all our institutions, and all our resources. . . . I believe the single most important thing our young people will need to meet this critical challenge in the years ahead is moral strength—and strength of character.

Much of Truman's speech was directed at the Communist threat to a democratic society. He did, however, make a tangential connection to the conference theme, "For Every Child a Fair Chance for a Healthy Personality."

The strength of character required to meet the challenges of a postwar world came from positive emotional and mental development. The growing interest in, and reliance on, psychology was a tool to be further explored. Said one report from the 1950 National Committee: "Various professions are discovering that the new findings in psychology, sociology, and physiology have important implications for their work. Parents, too, are learning about (some might say, are being engulfed by) the new ideas."

Certainly, a child's understanding of the world and his or her outlook were influenced by cultural background, economic status, and religious instruction. These variations and differences should be examined, said organizers. The ultimate goal was to produce an "emotionally and intellectually sound generation," even as youngsters were told that Communist infiltration and the threat of nuclear annihilation were very real.

When White House Conferences were initiated, a working theme was attached to the event. These provided some indication of the conference's primary focus. With each meeting, however, the theme became more esoteric.

Organizers of the 1960 conference faced a similar dilemma in adequately defining their goals with a slogan. The conference was labeled the Golden Anniversary, but the national committee decided to delete its theme, "Individual Fulfillment in a Changing World," from official statements and press releases. To organizers, no phrase adequately captured "the complex issues" at hand. The same was true of the 1970 conference, which worked from a broad outline of topics categorized by three age groups that spanned infancy to age 19.

The 1970 conference was the last of its kind. In the attempt to be all-inclusive, the conferences had become unwieldy. Beginning in 1950, the number of participants greatly expanded. Six thousand attended that meeting; 7,000 were at the 1960 conference. A few hundred of these were children and teenagers, invited to provide entertainment or attend as "youth" representatives.

The breadth of subjects and issues were also problematic. Conference participants worked in small groups according to their special expertise and interests. Some groups focused on research projects devoted to health care, education, and the influence of the mass media. Others studied laws that affected adoption, divorce, employment, institutionalization, and juvenile justice.

A number of groups looked at family life and community resources, as well as the role of recreation, discrimination, youth groups, and religious programs that in some way affected children and teenagers. In the end, work groups were expected to come together with recommendations and proposals. It was a daunting task, and as early as the 1950 conference, National Committee chair Oscar R. Ewing wondered if the delegates should "undertake detailed examination of all problems relating to children

or rather choose one or more specific problems and concentrate on these."

That approach became the norm after the 1970 conference, although in 2008, during the second session of Congress, H.R. 5461 called for a White House Conference on Children and Youth. Those who lobbied for the bill argued that this would reestablish the tradition that ended after 1970. Of course, White House conferences devoted to children and teenagers had not disappeared after that date. In most recent memory there have been the 1997 conference on Early Childhood Development and Learning, the 2000 conference on Teenagers, the 2002 conference on Missing, Exploited, and Runaway Children, and the 2005 conference on Helping America's Youth. Unlike the White House Conferences on Children and Youth, these meetings did not attempt to encompass a wide range of topics. They instead focused on defined groups, needs, and issues.

This trend to narrow discussion points actually began in the 1950s, when the White House Conferences on Children and Youth were still being held. During the Eisenhower administration, there were two initiatives aimed at specific areas. The first was the White House Conference on Education (1955) and then the President's Conference on Fitness of American Youth (1956).

Before the 1955 publication of Why Johnny Can't Read and before the Soviet's launch of Sputnik (which resulted in the National Defense Education Act of 1958), the Eisenhower administration was putting together a conference on education. Some problems went back to the war years when shortages curtailed school construction and when teachers (both male and female) left teaching for military service or work in war plants, and did not return to the classroom.

By the mid-fifties, the lack of teachers and the need for more classrooms and updated equipment became critical as the number of school-age children rapidly rose. Each year the number of children entering school increased by about 3 percent until, by the 1960–1961 school year, over 25 million children were in elementary school. In a letter to Clara Swinson, an African American teacher in Oklahoma, Eisenhower expressed his hope to limit "federal participation to what might be called emergency construction of the necessary buildings."

He understood that in theory and in practice, the American educational system rested on local school districts and state boards of education, and many of these feared that money for construction would be the first step toward federal control of education. Typical of this position was the opposition posed by an educator in Texas who argued that any form of aid would "lead to federal controls as well as reduce initiative for local supports."

States rights advocates, like this gentleman from Texas, were joined by others who, for their own reasons, made financial aid to education one of the most controversial issues in the postwar era. Northern conservatives opposed more government participation when it meant an increased federal budget; the Catholic Church resisted because federal aid would not include parochial schools; and lastly, there were those who blocked aid because parochial schools might be included.

Nevertheless, it was becoming more obvious, even imperative, said many, that the federal government offer more guidance and financial aid in the push to improve the nation's schools. The physical environment, including more classrooms, demanded immediate attention.

At the same time, the teacher shortage was a challenge, as was the growing expectation among parents and communities that classroom instruction expand beyond what was normally considered a common school education. They wanted their children exposed to modern languages, music, and art. Parents with physically or emotionally challenged children wanted expanded school services to meet those needs. "Everybody wanted to add something, and nobody wanted to cut anything out," observed one commentator in the September 1955 issue of Harper's Magazine.

Many within the federal government, in the military, and the scientific community took another view. They argued that U.S. security and military strength rested on the next generation of well-trained professionals in the sciences. In this context, baby boomers did not realize it, but they were in competition with the children of the Soviet Union.

While educators, communities, and the government wrestled with the needs of schools, another warning went up. Not only did "Johnny" have problems reading; he couldn't do push-ups.

In July 1955, Hans Kraus and Bonnie Prudden, co-authors of a number of articles related to physical fitness, gave a presentation at a White House luncheon largely attended by well-known amateur and professional athletes. Kraus and Prudden specifically referred to a study that compared American and European students between the ages of 6 and 16 using the Kraus-Weber Tests for Muscular Fitness. The test evaluated youngsters' abilities to do a set number of such things as leg lifts, sit-ups, and toe touches.

The results were disturbing. Only about 8 percent of the European children failed even one test component; 56 percent of the Americans failed at least one—and usually more. Subsequently, Eisenhower called for a President's Conference on the Fitness of American Youth with Vice President Richard Nixon serving as conference chairman.

The conference, convened in June 1956, wanted to give "form and substance to the idea of a physical fitness program for American youth." It encouraged increased participation in recreational and competitive sports, and it warned against "the sedentary habits of our age." Out of the conference emerged the President's Council on Youth Fitness (renamed the President's Council on Physical Fitness by President John F. Kennedy) and a Citizen's Advisory Committee "to help improve the physical and mental health of the nation's young people." Neither the council nor the committee operated a program that gave money to projects, but it was hoped that the groups' promotional work would "stimulate the initiative of the home and community," according to the council's administrator, Shane McCarthy.

Conferences directed at a specific topic and the White House Conferences of 1950 and 1960 were intended to do more than produce rhetoric and reports. They created a public forum for national discussion. They raised public awareness and educated the average American, along with elected officials and professionals.

Sometimes the end result was a conference-approved recommendation that asked the federal government to become more involved in some particular area. Despite the number of government programs that directly affected children, there was a general consensus that it could do more through legislation and funding.

Occasionally, reports and discussions asked the government to reconsider programs that, once implemented, produced more problems than anyone anticipated. Follow-up meetings to the 1960 conference, for instance, were critical of state and federal entities that rushed forward with urban renewal without giving much thought to relocating displaced families. There was also concern that vocational programs, funded with federal monies, were not preparing teenagers for jobs in a work environment of rapidly changing technology. While slum removal and vocational education could benefit youngsters, unforeseen consequences demanded their own solutions.

Other subjects, including the urgency to remedy the housing crunch of the late 1940s, receded into the background. However, many complex concerns, such as reducing juvenile delinquency or providing educational opportunities for all, remained constants in conference discussions. What was said about children and teenagers was fundamental to the conference process and to identifying needs and successes.

But, in that discourse we also find American society focusing on the sort of childhood experience and legacy it was creating for its younger generation. Children and teenagers of the postwar era were expected to have larger opportunities, better experiences, and more personal fulfillment than those who grew up during the Great Depression and war years. The White House Conferences attempted to help make that happen.

Marilyn Irvin Holt, formerly on the staff at the Kansas State Historical Society, has been a research consultant for PBS projects and specializes in topics related to childhood history. Her books include The Orphan Trains: Placing Out in America, Indian Orphanages, and Children of the Western Plains: The Nineteenth-Century Experience.

Note on Sources

Material pertinent to the White House conferences can be found in a number of places. Records for the 1970 conference are in the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, and the records for the 1930 meeting are housed at the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University.

The largest resource, however, is in the holdings of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas. The library's collection contains a number of publications issued by the 1930 and 1940 conferences, but the bulk of the records relate to the 1950 and 1960 meetings. (With the exception of personal letters written to President Truman by people wanting to participate in the conference, the 1950 records were not transferred to the Harry S. Truman Library but remained with the incoming administration and were added to the later 1960 records.) The collection at the Eisenhower Library also includes documentation of the mid-decade conference of 1965, which was a follow-up to the 1960 conference.

The White House Conference collection includes correspondence between government officials and participants, organizational materials, committee reports, and state reports compiled prior to the national conferences in Washington, D.C. This sort of extensive documentary material has not been located for the 1909, 1919, and 1940 conferences. It is possible that they no longer exist, although historians may find references to these conferences in the papers of the Presidents in office at the time and the first ladies.

The quoted letter from President Eisenhower to Mrs. Clara Swinson of September 7, 1957, is in box 547, 1957 file, Central File, Eisenhower Library. Records for the White House Conference on Education and the President's Conference on the Fitness of America Youth are held at the Eisenhower Library.

Published sources include White House Conference on Children in a Democracy, Washington, D.C., January 18–20, 1940 (Washington, D.C.: Superintendent of Documents, 1941); Edward A. Richards, ed., Proceedings of the Midcentury Conference on Children and Youth (Raleigh, NC: Heath Publications, 1959); David Fanshel, Far From the Reservation: The Transracial Adoption of American Indian Children (Mutchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1972); Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, rev. ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1999); and Shane MacCarthy, "Enjoy Keeping Fit," The American Recreation Society Bulletin 9 (May 1957): 6.

Articles in national magazines about juvenile delinquency include Marjorie Rittwagen, "Child Criminals are My Job," Saturday Evening Post 226 (March 27, 1954): 19–21; "Juvenile Crime: Is Your Boy Safe?—All Our Children," Newsweek 42 (Nov. 9, 1953): 28–30; and "Delinquency: Big and Bad," Newsweek 42 ( Nov. 30, 1953): 30.