All Hands on Deck: A Sailor's Life in 1812

By Sarah H. Watkins and Matthew Brenckle

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3

Ever wonder if a sailor’s life is for you? Visitors to “All Hands on Deck: A Sailor's Life in 1812,” the USS Constitution Museum’s newest exhibit, can find out. Designed to be both hands-on and minds-on, the exhibit allows families to scrub a deck, swing in a hammock, fire a cannon and furl a sail as they learn about history together. “All Hands on Deck” is the culmination of years of research into the lives and experiences of the men who served on board USS Constitution at the moment when the ship earned her nickname, “Old Ironsides,” and became a national symbol that endures today as one of Boston’s most famous attractions.

Fueled by research conducted at the National Archives, the exhibit brings the past to life using innovative interpretive techniques. Best of all, every aspect is informed by the hard won experiences of the men and women who lived through the War of 1812.

Because of her wartime exploits, the nation has preserved Constitution as a naval monument, a shrine to victories plucked from the mighty Royal Navy. While the ship’s status as a national symbol has ensured her survival, it has tended to obscure the people who made the ship’s victories possible. Thousands of individuals lived, worked, and fought on board her. The exhibit interprets Constitution from the inside out, giving voice for the first time to the ship's company.

By focusing on the people, including common seamen, officers and marines, the exhibit allows visitors to look beyond tactics and technology. The exhibit examines sailors’ motivations for enlisting and how they adjusted to life in the self0contained wooden world. It also offers a glimpse of life ashore, considering who and what the sailors left behind and the impact of separation and loss on seaside communities.

As “All Hands on Deck” demonstrates, when sailors entered the highly regulated, interdependent shipboard community, they were forced to endure psychological and physical hardship for the sake of ship and country. Their shared experience forged an emotional bond among shipmates and led them to regard their messmates as a surrogate family. For them, the ship was home.

The exhibit’s final section shows how the crew's participation in naval victories over Great Britain during the War of 1812 contributed to America's emerging national identity. The story of Constitution and her crew is particularly timely as our country prepares for the bicentennial of the War of 1812.

Visitors Prepare To Go to Sea as Sailors on USS Constitution

When visitors enter “All Hands on Deck,” they experience the bustle of a busy Boston waterfront as provisions and livestock are hoisted aboard. Handbills posted on the walls indicate that they are approaching a recruiting office for USS Constitution. Here visitors first encounter life-sized photo cutouts of sailors and civilians. Using the physical descriptions of actual individuals from the time—age, height, eye and hair color, and scars or tattoos, all gleaned from size rolls (physical descriptions and enlistment details of marine privates and NCOs), prisoner-of-war records, and seaman protection certificates—we sought actors who had the right look and fit the sailors’ profiles.

An extensive review of clothing receipts in Treasury accounts and Navy contract proposals at the National Archives told us exactly what Constitution’s men wore and allowed us to create a wardrobe of hand-sewn garments. Skilled make-up artists gave the actors the ruddy cheeks and dirty hands of real weather-beaten tars. A professional photographer captured these men in high-resolution action. These figures permanently populate the exhibit and lend an unrivaled level of character and verisimilitude to the surroundings.

Outside the “House of Rendezvous” (temporary recruiting office), visitors see an original broadside notifying citizens that “War is declared.” Lt. Charles W. Morgan, responsible for recruiting, invites visitors into the waterfront building to serve their country and fight for “free trade and sailors’ rights.”

Inside, visitors take turns acting as recruiter and recruit. The recruiter asks the recruit a series of questions to gauge his or her potential as a sailor. Some questions elicit laughs, others looks of disbelief or disgust. For instance, the recruiter asks, “have you ever swung in a hammock? Are you willing to sleep next to 200 of your closest friends who are badly in need of a bath?” The recruiter tallies the answers and the recruit joins the crew.

Next, artifacts and text panels prompt visitors to think about what sailors needed to bring to sea with them and what it was like to bid farewell to loved ones. Once on deck, they are “welcomed” on board by a musket-wielding marine sentry who warns them that they must do their duty or suffer the consequences. The space mimics Constitution’s deck, with planking below, rigging above, the bulwarks of the ship on either side, and sounds of the ship and sea.

Learning To Be the Newest Recruits on Board USS Constitution

New recruits who need clothes can buy supplies from the purser and discover how quickly these purchases consume their wages. Treasury accounts provided the historical prices charged for “slops”—ready-made clothing and other sundries like chocolate, soap, and tobacco. “Below decks” the low ceilings and minimal lighting simulate the dark, crowded, stuffy and wet living quarters of the crew. Visitors can climb into a hammock and swing side by side with their friends. Questions on the beams overhead ask them to think about the lack of personal space and some of the “sea miseries” experienced by sailors.

Across the deck from the hammocks stands a low, black iron stove, a miniaturized version of a ship’s “camboose” copied from drawings and descriptions in the Board of Navy Commissioners correspondence.

Using faux rations, children can concoct a sailor’s stew and serve it to their friends. Gathered “picnic-style” around a black painted cloth, visitors bond over salt pork, ship's biscuit, and grog. In the words of one contemporary sailor, messes were “little communities of about eight. . . . These eat and drink together, and are, as it were, so many families.”

Tough Work Awaits on Deck and So Does Tough Discipline

Back on deck, the real work begins. Visitors are encouraged to try their hands at typical sailor tasks. They are given a reproduction holystone and told to get on their knees and scrub the deck. To convey different perspectives, this object is seen from the point of view of a sailor for whom it represented daily monotonous labor and the first lieutenant who felt pride in the glistening ship and saw the advantages of keeping hundreds of men busy each morning.

Activities that require teamwork for success, such as furling a sail, highlight the physical skill and mental stamina required to sail a ship. As visitors approach the yard, they see a film showing sailors aloft taking in a sail at sea. The camera moves with the vessel, giving the impression that one is swaying high above the deck.

Once visitors step off the ground to balance on the footrope slung below the yard, they work together to pull in a heavy sail. The yard and sail are surrounded by images of sailors working aloft. Nearby, an 1820s journal delineates the station of each crewmember in the top and on the yards.

A sailor’s life is full of strife, goes the old song, and interpersonal conflict was a fact of life on a wooden warship. Discipline in some measure ameliorated shipboard disagreements. Visitors view an original 19th-century cat-o'-nine-tails, which to a sailor it represented humiliation, lack of control, and a constant threat. But from the captain’s perspective, it was a necessary evil to control the crew’s bad behavior.

The Effects of Battle on Crew: Glory and the Scars of War

Without well-trained gun crews to aim and fire its many cannon, a warship was useless. Visitors can learn about the training and teamwork required to fire a cannon on Constitution. A video shows Constitution's 21st-century crew demonstrating the steps required to load a gun that weighs nearly 7,000 pounds. Visitors can haul on the lines of a replica 32-pound carronade and see if they are strong enough and fast enough to prepare it for firing.

Once the visitor-recruits feel confident that they have what it takes to conquer an enemy in battle, they can enter the “battle theater.” This multimedia show combines historic images, narration, objects, and faces of sailors illuminated in sequence with the story. In his own words, Seamen David C. Bunnell, an 1812 sailor, describes the tension before battle: “The word ‘silence’ was given—we stood in awful impatience. . . . My pulse beat quick—all nature seemed wrapped in awful suspense—the dart of death hung as it were trembling by a single hair, and no one knew on whose head it would fall.”

Other crewmembers share their own sentiments. Young Midshipman Whipple expresses his excitement and a strong sense of patriotism before going into battle for the first time: “It appears to me at present that a man must be happy who sacrifices everything for his country . . . should I be so fortunate as to prove serviceable to my country, I shall be in the zenith of my glory.”

Whipple's words return after the battle: “This being the first action I was ever in, you can imagine to yourself what my feelings to hear the horrid groans of the wounded and dying.”

The battle presentation also explores how combatants’ attitudes toward their opponents changed after the inhumanity of battle. No longer “boasting tyrants” or “faceless monsters,” sailors on opposing sides enjoy some moments of camaraderie, even as the surgeons work frantically to remove shattered limbs and staunch the bloody wounds.

“All Hands on Deck” concludes with the crew and ship returning home to a hero’s welcome. Here visitors learn what USS Constitution meant to her crew and to the country as a whole and discover the fate of the sailors profiled in the exhibit.

How Do We Know What We Know? Finding Answers at the Archives

Who were the 1,171 men who served on Constitution between 1812 and 1815? How do we resurrect these fellows from the murky depths of history to which they’ve been consigned?

At the core of “All Hands on Deck” lies a major research effort that began in 2001 and that built on 30 years of research by Tyrone G. Martin, former commanding officer of USS Constitution and author of A Most Fortunate Ship (for more of Martin’s Constitution research, visit thecaptainsclerk.com).

According to scholars who advised the exhibit in its planning stages, no other maritime museum has attempted an in-depth look at the lives of ordinary seamen from a single ship. This approach presented a formidable research challenge. Museum staff mined the records of dozens of repositories across the country.

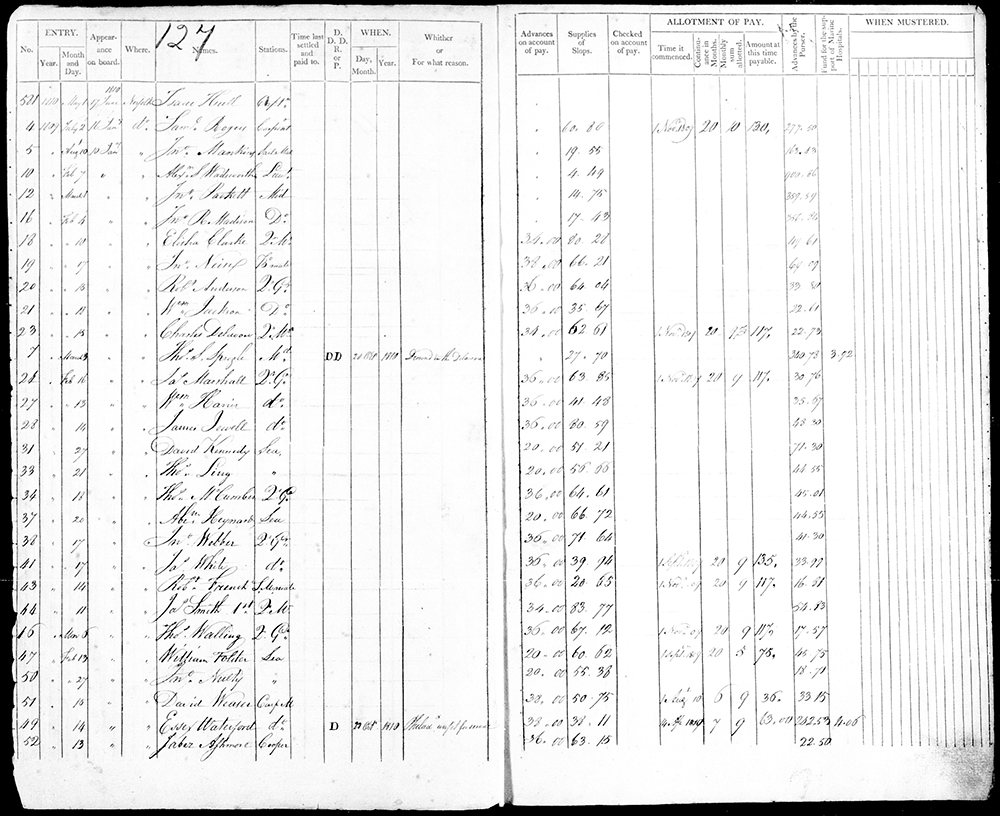

The single most important, however, was the National Archives and Records Administration. Among NARA’s many fantastic holdings, we find Constitution's logbooks, muster roles (lists of crew), Marine Corps size roles, pension records, and official Navy correspondence.

Unfortunately, the Navy kept fairly cursory records about the crew. The ship’s muster rolls recorded a sailor’s name, rank, date of entry and discharge, and that’s about it. No age, no place of origin, no physical description—nothing that could help us positively identify them in other records. Add to this the fact that some, especially those born in Great Britain, might have been serving under false names, and the research challenges become apparent.

Luckily, there were other ways to track them down. Paradoxically, the worse a sailor’s life, the more we know about him. Most men served faithfully for two years and then faded from the record. But a long and often detailed paper trail followed those who suffered life-altering wounds or accidents.

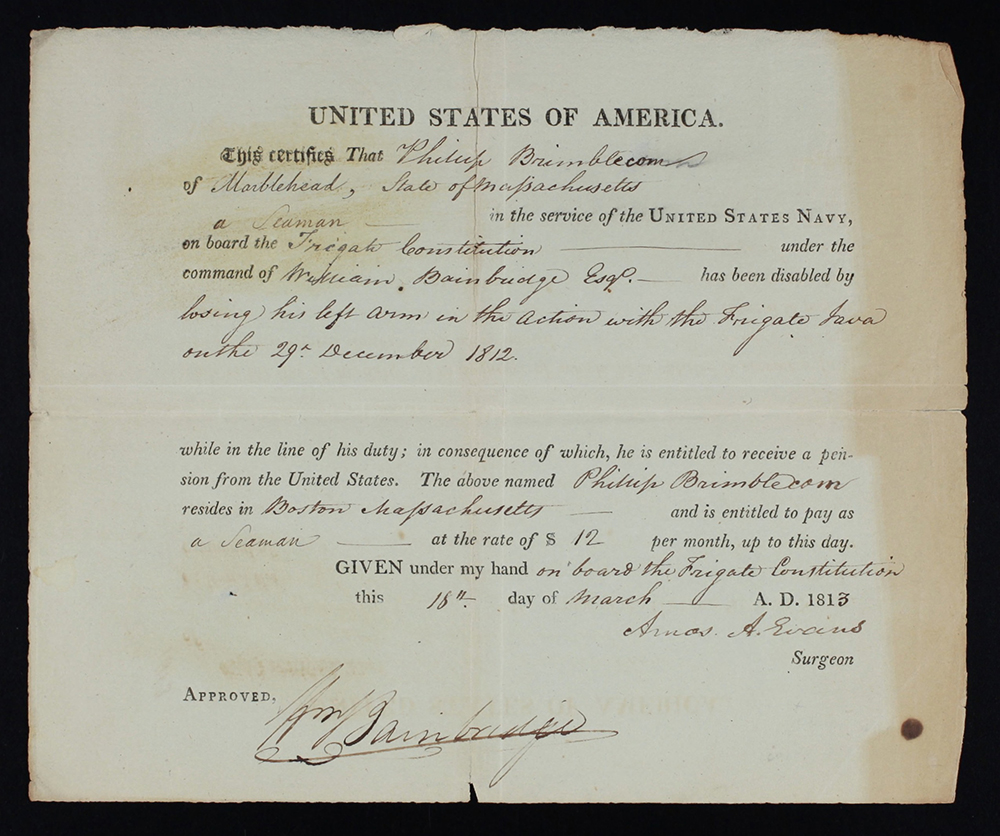

The most illuminating source has been the Navy pension applications. If a sailor received a wound or was otherwise disabled in the course of his duty, he was eligible for a monthly stipend from the government (usually equal to half his pay). To receive this payment, however, he had to prove that he had in fact been in the service and that he had been disabled.

This means that all the files contain affidavits and declarations by all sorts of people, including the applicant sailor himself. Nearly 150 of Constitution’s seamen and officers applied for pensions. Widows and minor orphans of seamen and officers were also eligible for government assistance, and many applied for relief too. So that gives us a great body of information to work from. When we combine these sources with the usual birth, marriage, and death records, court transcripts, and related documents, we can really begin to recreate what their lives were like.

Of the nearly 1,200 who served, we now have good information on about 500. Some of the stories are harrowing and starkly illustrate the dangers of seafaring in the early Republic.

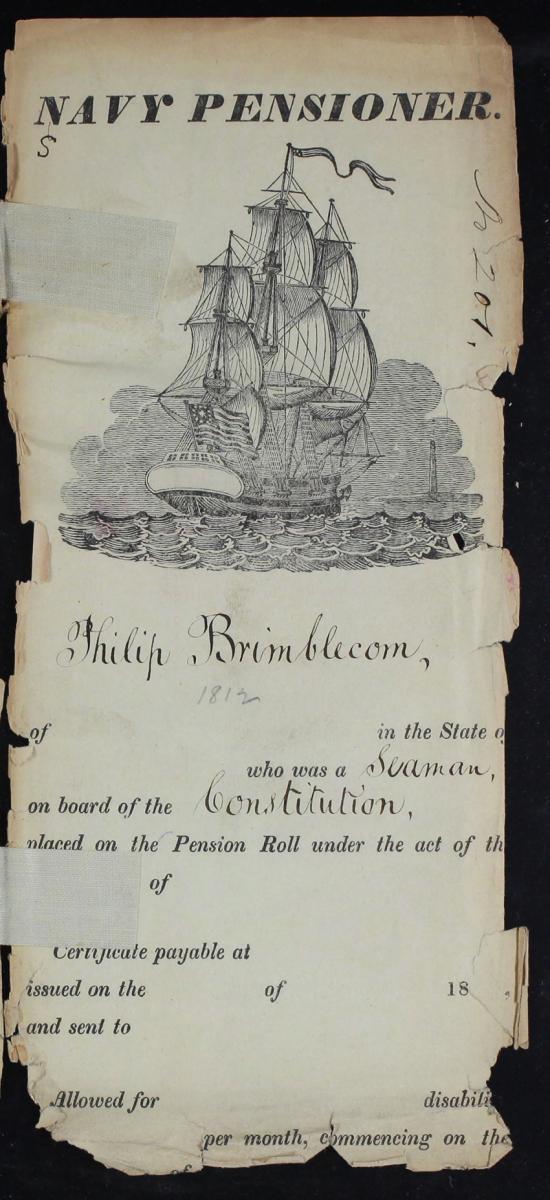

The Unlucky Life of a Sailor: The File on Philip Brimblecom

One of the unfortunates was named Philip Brimblecom. Born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, in 1786, he launched his career like many other young men in town, by going to sea in search of cod. In 1809, he gave up the hook and line and shipped on board his uncle’s schooner, the Springbird, for a voyage to Spain. Here his life took a turn for the worse. Off the coast of Spain, a French privateer captured the Springbird. Unemployed and with nowhere to go, Brimblecom shipped on a French merchantman bound for the Indian Ocean. Four days out, a British cruiser took the ship, and Brimblecom found himself a prisoner of the Royal Navy. He was sent to England and imprisoned.

In October 1810, Philip managed to send a letter to his mother, Hannah, in which he described his ordeal. America was not yet at war with England, and Americans should not have been held as prisoners of war. Hannah sent Philip’s protection certificate and baptismal record to the American consulate in London to prove that her son was an American citizen.

The consul responded that the English considered Brimblecom a prisoner of war because he had been captured while serving on a French privateer. Not pleased by this response, Mrs. Brimblecom had a friend request help from Secretary of State James Madison.

Meanwhile, the British took Brimblecom from prison and forced him to serve on board HMS Marlin. Not willing to wait for a diplomatic resolution to his ordeal, he made his escape in the spring of 1812 and entered on board a ship bound for Newburyport, Massachusetts. Continuing his string of bad luck, the ship wrecked on the Orkney Islands.

Brimblecom and his shipmates traveled from those bleak islands to Scotland, where he boarded an American brig. By then, America had declared war on Britain, and during the voyage across the Atlantic, the British captured Brimblecom again. They took him to Newfoundland, where he was exchanged in September 1812.

At the age of 26, Brimblecom had experienced enough misfortune to last most men several lifetimes. His next step made sense for one who must have seethed with a desire for vengeance. On September 25, 1812, he enlisted as an able seaman on board Constitution. The ship had just returned victorious from an encounter with HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia, and her new captain, William Bainbridge, had no trouble recruiting men to serve on the lucky vessel.

The ship’s luck did not rub off on Brimblecom. As Constitution sailed south during October and November, the sailors frequently “exercised at the great guns,” learning to perform their duties with speed and accuracy.

According to the ship’s “quarter bill,” Brimblecom served as the first loader to gun number one on the gun deck. It was a dangerous position, and he did his duty there on December 29, 1812, when Constitution encountered HMS Java off Brazil in a hard-fought battle. In the midst of the action, as Brimblecom bent to load the gun, a British cannonball shattered his arm below the elbow. Surgeon Amos Evans amputated the limb, and although the stump quickly healed, the young sailor remained in constant pain.

With only one arm, Brimblecom couldn’t work as a seaman, the only work he’d ever known. Twice he wrote to the Navy seeking employment and for an increase in his six-dollar monthly pension, which he and his mother relied on. He complained, “some of the rest that was wounded with me has had an addition to their pension money.”

Brimblecom got a job at the Charlestown Navy Yard in 1816, and at the Portsmouth Navy Yard the following year. By 1820 he was unable “to do anything for a living,” and since he had “no friends on earth,” he asked the government to take his request “into consideration and look after a poor distressed crippled sailor” who “for 22 long months . . . [has] never seen a well day.” The response, if any, to his final request is unknown. Philip Brimblecom died of a fever on February 1, 1824 in Marblehead. He was only 37 years old.

The Strange Case of David Debias: A Free Black Sailor Wanders into Slavery

The records at the National Archives have also helped resolve at least one mystery.

In 1814, an eight-year-old African American boy named David Debias joined Constitution’s crew. David was born free on Belknap Street in Boston. In the early 19th century, seafaring was one of only a few jobs that offered free African Americans not only a living wage, but also a respectable career with equal pay. Though racism was not absent aboard ships, free black sailors were integrated into the enlisted shipboard community—sleeping, eating, and working side by side with their white counterparts. Historians estimate that during the War of 1812, 7 percent to 15 percent of sailors were free men of color.

A month after joining Constitution's crew, Debias participated in "Old Ironsides’" victory over two British ships, HMS Cyane and HMS Levant on the night of February 20 1815. Transferred to the Levant with the prize crew, he was taken prisoner when the British recaptured the ship at Porto Praya in the Cape Verde Islands. After a stint in a Barbados prison, he returned to Boston.

David remained with his parents for some time and then shipped as a sailor on several merchant voyages. In 1821 he again shipped on board Constitution. Commanded by Capt. Jacob Jones, the frigate sailed for the Mediterranean, where the young man no doubt marveled at the wonders of the ancient world. The ship touched at Leghorn, Gibraltar, Malaga, Port Mahon, Genoa, Leghorn, Naples, Malta, Algiers, and Smyrna, and finally came home to New York. Debias left the service then and sailed in other merchant ships. Sometime in 1838, his ship docked in Mobile, Alabama. For some unexplained reason, David left the ship and started walking north. In Wayne County, Mississippi, he was arrested as a runaway slave.

After hearing David’s story and believing him the victim of a grave injustice, a local lawyer and state senator named Thomas P. Falconer took up his cause. Falconer wrote to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson “for evidence from the Navy Department in behalf of an individual who has been arrested here as a slave. I have not the least doubt of his freedom, but his appearance may force upon him the onus probandi of freedom. He is a stranger in a strange land and from the rigidness of the law in the absence of testimony may be deprived of his liberty.”

For years, we wondered about the fate of David Debias. Did Secretary Dickerson respond to this request? Was he freed or sold into slavery? Finally, in fall 2010, thanks to archivist Trevor Plante at the Archives, the mystery was solved. On April 17, 1838, Secretary Dickerson forwarded to Mr. Falconer an “authoritative certificate by the 4th Auditor of the Treasury,” proving that David Debias had in fact served on Constitution. Because the Wayne County Court House burned down in the 19th century, all the court records from the 1830s have been lost. Still, we can reasonably assume that this significant piece of evidence was sufficient to free David.

The Impact of the Research on Study of the War of 1812

The research into the individuals who served on board Constitution allows the museum to breathe new life into the ship's history. By telling the story of life on board USS Constitution through the sailors who experienced it, “All Hands on Deck” allows visitors to connect to the past in a personal way.

One teacher remarked: “It's a wonderful way to make history come alive and become real to my fifth graders. As one of my students said this year, ‘history like this is fun, because it's about us.’” The exhibit’s humanistic viewpoint and participatory approach has demonstrated the potential to change how children view history—children like Kelly, age 10, who reported, “I used to think history was boring, now I ❤ it!”

To expand the reach of the research in advance of the bicentennial of the War of 1812, the USS Constitution Museum launched an online game and educational resource that brings the teeming humanity of the ship to life for a virtual audience (asailorslifeforme.org). The award-winning site allows users to experience the life of an 1812 sailor and scrub the deck, whack rats in the hold, tell tall tales, steer the ship, and fire a cannon.

The site also includes curriculum material for teachers who want to teach about the War of 1812 and USS Constitution, and Discovery Kits are being made available to public libraries across the country for families to check out.

The bicentennial of the War of 1812 provides a singular opportunity to engage all ages in conversation and discovery about USS Constitution and the War of 1812. Thanks to the records available at the National Archives, students and families will discover that history is about individuals like themselves, just separated by time. Through the USS Constitution Museum's exhibit, website, and library kit, students and families learn that history can be exciting, meaningful, and personally relevant.

Sarah H. Watkins is curator and Matthew Brenckle is research historian at the USS Constitution Museum. Founded in 1972, the USS Constitution Museum is a private not-for-profit institution, serving as the memory and educational voice of “Old Ironsides.” Open 7 days a week, 362 days a year, the Museum welcomes over 300,000 annual visitors free of charge.

Notes on Sources

Constitution’s 1812 logbooks are microfilmed on Logbooks and Journals of the U.S.S. Constitution, 1798–1934 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1030), vols. 3 and 4. The ship’s muster rolls are microfilmed on Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T829). Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798–1892 are on National Archives Microfilm Publication T1118. Boston Navy Agent Amos Binney’s purchasing receipts for Constitution come from the Accounts of the Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group (RG) 217, boxes 38 and 39. In the Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, RG 127, are size rolls, which record name, rank, birthplace and date, date and length of enlistment, officer who enlisted the marine, height, hair and eye color, complexion, previous occupation, and remarks detailing service in the cops. Clothing proposals sent to the Board of Navy Commissioners can be found in Proposals, Reports, and Estimates for Supplies and Equipment, 1814–1833, Vol. 4, E-328, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, RG 45.

Philip Brimblecom’s pension application is in War of 1812 Navy Invalid File #201, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15,. His mother’s correspondence with James Monroe and his protection certificate are in Letters Received by the Department of State Regarding Impressed Seamen, 1794-1815, General Records of the Department of State, RG 59,. The Bainbridge Battle Bill is in Series 464, box 222 Subject Files 1775–1910, RG45. Thomas Falconer’s 1838 letter to Mahlon Dickerson is in Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy: Miscellaneous Letters, 1801–1884 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M124). The secretary’s reply is in Entry 6, Miscellaneous Letters Sent, (General Letter Books), Vol. 24, page 403, RG 45.