Leaving the Army During Mr. Madison's War

Certificates of Discharge for the War of 1812

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By John P. Deeben and Claire Prechtel-Kluskens

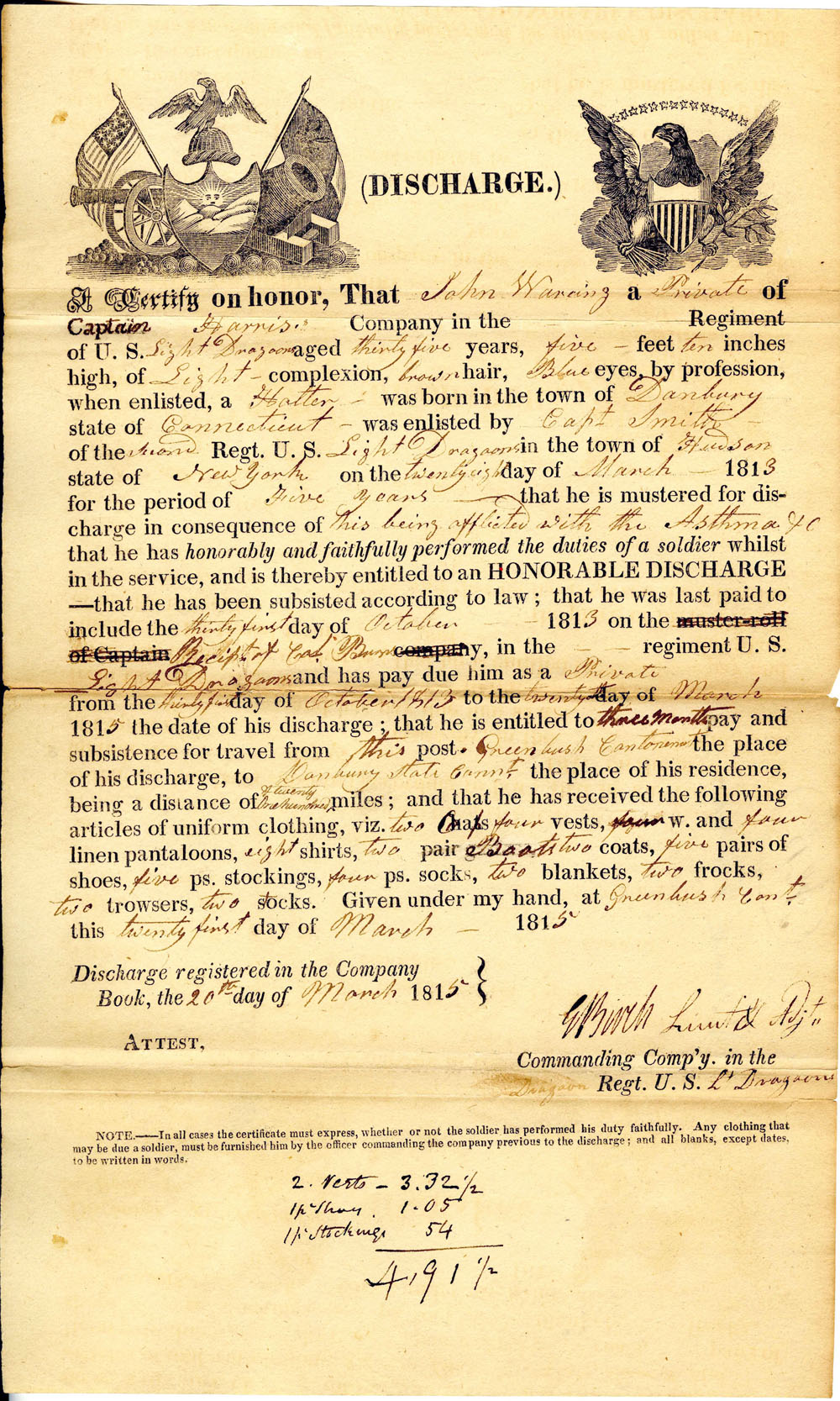

John Warring enlisted in the Second U.S. Light Dragoons at Hudson, New York, on March 28, 1813.1 The 35-year-old hatter from Danbury, Connecticut, was a bit older than most of his fellow recruits, but the economic effects of the second war against Great Britain that erupted nine months earlier on June 18, 1812, may have dampened demand for headgear produced by his smelly, messy, and even dangerous occupation.

Although he enlisted for five years, Warring's military career ended early when he received an honorable discharge on March 21, 1815, "in consequence of his being afflicted with the Asthma, &c." Warring received the balance of his military pay dating from October 31, 1813, as well as three months' pay and subsistence to travel from his current post at Greenbush Cantonment (headquarters of the Northern Division of the U.S. Army) in upstate New York to Danbury, some 120 miles away. Warring also returned home well supplied with the balance of his Army-issued clothing, including two caps, four vests, four linen pantaloons, eight shirts, two pairs of boots, five pairs of shoes and stockings, two coats, four pairs of socks, two blankets, two frocks, two trousers, and two stocks.2

Such a succinct, detailed summary of Warring's military service comes from an unlikely but obvious source: his military discharge certificate. In the 19th century, soldiers discharged from the Regular or volunteer armies usually received a certificate to document their formal separation from the Army. The discharge certificate became the veteran's personal property—the War Department generally did not retain file copies—and in time, an honored memento of their military service.3

Because they remained in private hands, carefully preserved (or not) by the soldier or his heirs, discharge certificates are usually difficult to locate and are seldom available for public research. One notable exception, however, is a small series of extant discharge certificates and other records relating to more than 2,200 Regular Army soldiers from 1792 to 1815. The majority of these records provide an otherwise unavailable source of information for service during the War of 1812.

As the War of 1812 Intensifies, The Regular Army Grows

After Congress established the War Department on August 7, 1789 (1 Stat. 49), the Regular Army constituted the principal armed force of the United States. During the early years of the Republic, the Regular Army comprised a relatively small fighting force supplemented by regiments of volunteers or state militia units during specific national emergencies, including Indian wars, the Whiskey Rebellion, and other conflicts. At the declaration of war with Great Britain on June 18, 1812, the Regular Army consisted of about 10,000 men, half of whom were new recruits. An act of June 26, 1812 (2 Stat. 764) increased the size of the Regular Army to a total authorized strength of 36,700 men. An act of January 29, 1813 (2 Stat. 794–797), added 20 additional infantry regiments for one year's service. In addition to these troops, volunteer regiments and federalized state militia also took part in the conflict.4

The War Department recruited each Regular Army infantry regiment from a particular state (or states), while rifle, artillery, and dragoons were recruited at large. Most, but not all, of the men recruited for a particular regiment hailed from the state of recruitment. A useful source to identify regimental recruiting districts includes William A. Gordon, A Compilation of the Registers of the Army of the United States from 1815 to 1837 (Washington, DC: James C. Dunn, 1837). At the beginning of the war, recruits typically signed on for five years of service, although later recruits could enlist for the duration of the conflict. Congress offered initial enlistment bounties of $31 and 160 acres of land, later increased to $124 and 320 acres.5

Although the Regular Army did not become an effective fighting force until the final year of the war, it served with distinction in many major engagements. U.S. Regulars and New York militia under Maj. Gen. Stephen Van Rensselaer fought (and lost) the first major battle of the war at Queenston Heights, Ontario, on October 12, 1812, during the initial American invasion of Canada. Regulars and militia under Brig. Gen. Jacob Brown defeated a British invasion of New York at the Battle of Sackett's Harbor on May 28–29, 1813. Other engagements included the Battle of the Thames (October 5, 1813), Chrysler's Farm (November 11, 1813), and Chippewa (July 5, 1814)—the latter a decisive victory against British Regulars. U.S. dragoons under Generals John Coffee and Andrew Jackson also participated in Creek Indian campaigns during the war, including the battles of Tallushatchee (November 3, 1813), Talladega (November 9, 1813), and Horseshoe Bend (March 27, 1814).

The pay system in the Regular Army never worked efficiently. During the course of the war, the average soldier received from five dollars to eight dollars a month—less than the earnings of an unskilled laborer—and administrative inefficiency and slow communication often hindered regular payment. By the end of 1814, monthly payrolls were 6 to 12 months or more behind schedule, even though by law Army pay was not supposed to be more than two months in arrears "unless the circumstances of the case should render it unavoidable."6 In order to collect back pay upon being discharged, many soldiers—such as John Warring, who finally collected 17 months' back pay when he left the Army in 1815—returned their discharge certificates to a War Department paymaster to collect the money. Numbers and other handwritten calculations upon the face of the discharge records suggest that they were used in connection with the payment of arrearages.7

Discharge Certificates Provide Portraits of Army Soldiers

At the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), War of 1812 discharge certificates are located in Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917. They are part of the series "Post Revolutionary War Papers, 1784–1815" (Entry 19), which also includes records of various money accounts (requisitions, vouchers, and receipts) relating to the payment of Regular and volunteer soldiers and construction of military installations, as well as returns for clothing, provisions, and forage; enlistment papers; and pay and muster rolls.8

The discharge records have been reproduced as National Archives Microfilm Publication M1856, Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records Relating to the Discharge of Soldiers from the Regular Army, 1792–1815 (6 rolls), available at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and most NARA regional archives.

The discharge certificates relate solely to soldiers in the Regular Army primarily during 1812–1815; no militiamen or volunteers are included, although several civilians are mentioned. The certificate of discharge unambiguously states that the soldier was released from service on a particular day and may indicate the reason for separation. It also typically includes the dates of the soldier's enlistment and discharge, the company and regiment in which he served, the amount and kinds of clothing provided to him, and the period for which he was due pay upon discharge. The discharge may also provide his place of birth, age, physical description, and occupation. Such personal information was often included to deter improper usage in the event the discharge was lost or stolen from the veteran.9 The discharge of Gabriel Caves (39th U.S. Infantry) bluntly indicates the reason for detailing his physical description was "to prevent fraud."10

In addition to the discharge certificates, the records in the series include descriptive lists, certificates of death, and pay vouchers. The descriptive list provides a depiction of the soldier and may indicate the clothing and other supplies furnished him. Some are in chart form, while others are in narrative paragraphs. Both types sometimes indicate that the information was extracted from the company's record book.

The descriptive list of William T. Smith (16th U.S. Infantry), in chart form, indicates his age (19 years); physical description (5 feet 4 inches in height, with dark eyes, light hair, and fair complexion); place of birth (New York); date, place, and term of enlistment (November 30, 1814, at Philadelphia for the duration of the war) and the name of the recruiting officer (Ensign Eldridge); occupation (not stated); amount of bounty paid ($50) and amount due ($74); amount of pay due; and the number and type of clothing issued to him. Finally, the officer's certification indicates the information was "taken from the Company Book."11

Some descriptive lists provide additional information about the soldier, such as injuries and character of service. When Stephen McCarrier (14th U.S. Infantry) left the Army on March 13, 1815, the descriptive summary written by Lt. William G. Mills noted that McCarrier "had two fingers cut off his right hand while building hutts [sic] for the Regiment at Buffalo" on November 20, 1814. Despite the injury, McCarrier completed his service in exemplary fashion; the description noted he received an honorable discharge for "having in every instance, well performed his duty as a Soldier during the term he has served." The descriptive list for McCarrier's fellow company member, Samuel Barnes, likewise noted he "was wounded in both hands . . . in the action at Lyons Creek, Upper Canada" on October 19, 1814, while the discharge certificate for Thomas Webster (Corps of Artillery) documented the loss of a leg in November 1813 "by an accidental Musket shot" from a fellow artilleryman.12

Certificates of Death Provide Detailed Descriptions of Deaths

Certificates of death, both handwritten and in printed form, usually provide a brief statement of the soldier's date of death and the unit in which he served. The certificate for Henry Carman simply identified the deceased as a member of the Second U.S. Artillery who died at the general military hospital in Philadelphia on February 28, 1814. Other certificates sometimes identified the circumstances surrounding a soldier's demise, whether from illness, accidental injuries, or battlefield wounds. The death certificate for William Peters of Towson's Company, Second U.S. Artillery, indicated he "was wounded at the battle of Stoney Creek [in] Upper Canada & died at Lewistown Hospital, sometime in the month of September 1813." The certificate was signed in Philadelphia by Hospital Surgeon's Mate Edward Purcell as well as regimental Surgeon's Mate L. L. Near.13

Printed death certificates often included more information regarding the soldier's service. The certificate for William Hutchins (21st U.S. Infantry) noted he "served the U.S. honestly and faithfully, from the Twelfth day of March 1814, the date of his enlistment, to the Twenty-fifth day of Febr[uar]y 1815, at which day he died at Williamsville, N. York." He had received a 50-dollar bounty, and after his death, Hutchins's arms and accoutrements were returned to the regiment in good order. In addition to Army pay due for his full term of service, Hutchins was also "entitled to fifty dollars retained bounty & 160 acres of land and to the additional allowance of three months pay." In all other respects, the certificate resembled a typical discharge record, providing a list of clothing issued and a physical description that included Hutchins's age (20), occupation (farmer), and place of birth (Fryeburg, Massachusetts).14

Pay vouchers—handwritten or printed receipts issued by regimental paymasters (or sometimes the paymaster of the military district)—usually indicate the amount of pay due and/or the period of time for which pay was due. A voucher for Pleasant Hazelwood, issued by U.S. Army Paymaster George Merchant at Albany, New York, on April 23, 1813, stated that Hazelwood was a private in Capt. Joseph Seldon's Company, Second Regiment of Light Dragoons, and "has received his pay as appears by Capt. Seldon's Roll, now in my Possession, to include [back pay from] the thirty first [day of] December 1812." A pay voucher for deceased artillerist Henry Carman acknowledged pay due from October 31, 1813, to the date of Carman's death on February 28, 1814, as well as an eight-dollar bounty. Since Carman "Served faithfully until his Death," the voucher also authorized three months of extra pay (although it did not specify to whom the outstanding sums should be remitted on behalf of the deceased).15

Collectively, the discharge records reveal a few generalities about the men who served in the Regular Army during the War of 1812. Most were of typical military age (20s–30s), but a few were considerably older, such as Drury Hudson (20th U.S. Infantry), who was 60, and Solomon Stanton (25th U.S. Infantry), aged 54. A small percentage of African Americans also served with the Regulars, usually designated in their physical descriptions as "black," "negro," or "mulatto." (Soldiers described as "dark" were likely dark-skinned Caucasians). African Americans identified in the records include Richard Boyington (Fourth U.S. Infantry), who served the duration of the war from June 25, 1812, to May 18, 1815; George B. Graves (14th U.S. Infantry), who enlisted on August 2, 1814; and seven members of the 26th U.S. Infantry, including Hosea Conner, John Cooper, Joseph Freeman, Charles Matthias, Samuel Morris, John Peters, and William Smith.16

Subsidiary Discharge Records Add Even More Detail about Soldiers

Other supporting records can also appear with, or sometimes in place of, the main types of discharge papers. In addition to official certificates, some separations from service are documented by a simple note from the commanding officer recommending a discharge. Capt. Samuel D. Harris, Second U.S. Light Dragoons, issued such a recommendation for Elisha Harrington. The endorsement stated that Harrington "has served for and during eighteen months; his term of service having expired on the 4th day of December 1813 he is entitled to an honorable discharge." A recommendation for a temporary furlough rather than discharge also appears for George Shippey (Light Dragoons), who received three months' leave to return home from April 1 to June 30, 1815. Shippey earned the furlough for "uniform sobriety, and general good conduct" while serving as an orderly to Brig. Gen. Edmund Gaines during the British siege of Fort Erie on August 15, 1814.17

Records of enlistment, including the procurement of substitutes, are part of this record series for a few soldiers. A handwritten enlistment paper for Andrew McMillen showed he joined the 23rd U.S. Infantry on May 17, 1812, for 18 months "unless sooner discharged by proper authority," and also included an oath of allegiance to serve the United States "honestly and faithfully against their enemies" and to obey the orders of the President and "the officers appointed over me according to the rules and articles of war."18 When John Miller—a 35-year-old blacksmith from Bridgewater, Massachusetts—enlisted in Capt. George Haig's Company, First U.S. Light Dragoons, at Sackett's Harbor, New York, on August 4, 1813, he presented himself as a substitute for James Coveart. (Coveart had originally enlisted on January 9, 1809, but apparently decided not to finish his five-year term of service. The record sheds no light on how Coveart arranged the substitution). Miller subsequently reenlisted on January 9, 1814.19

Some of the pay vouchers also include records relating to officers' subsistence accounts. One such account for 2nd Lt. Rodolphus Simons (23rd U.S. Infantry) offers a detailed picture of his total financial compensation for military service. From August 1, 1813 to February 28, 1814, Simons received $175 ($25 a month) as well as two rations per day (for 212 days) at 20 cents per ration ($84.80). From October 3, 1813 to February 18, 1814, Simons also employed a "waiter" or personal servant, who likewise received $36.28 in military pay ($8 a month) as well as one ration per day (for 138 days), also at 20 cents per ration ($27.60). The final reimbursement to Simons totaled $323.68, which he verified as "accurate and just." Simons also certified that he had not "drawn rations in kind from the United States, or received Money in lieu thereof, for or during any part of the time therein charged."20

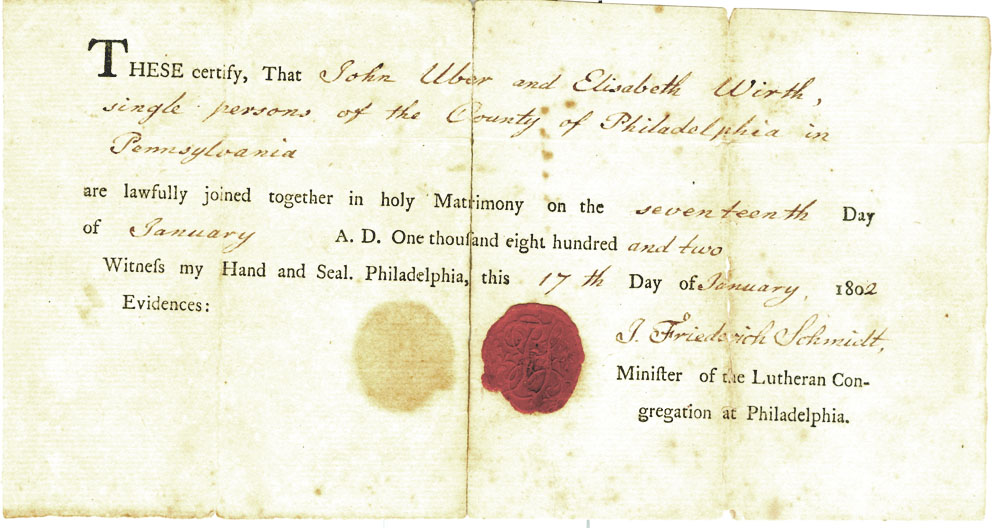

For several soldiers who died during the war, additional records document birth or marriage information. The death certificate for William Briggs (Ninth U.S. Infantry) includes an affidavit from his father, Thomas Briggs, who served in the same unit. In the deposition, Thomas verified that William was "begotten on the body of his wife Mary" in May, 1795, at Thomastown, Massachusetts.21 A handwritten marriage certificate also accompanied the death notice for John Uber (15th U.S. Infantry), who was killed at the Battle of York on April 27, 1813, showing he and Elizabeth Wirth of Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, were "lawfully joined together in holy matrimony" on January 17, 1802, by Rev. J. Friederich Schmidt, "Minister of the Lutheran Congregation at Philadelphia." A similar certificate for deceased artillerist Henry Carman confirmed his marriage to Deborah Bowen of Cumberland County, New Jersey, on April 14, 1810, solemnized by the Rev. Holmes Parvin.22

Some affidavits establish familial relationships while addressing legal issues relating to service. Several sworn statements occur from parents of minor-aged soldiers who enlisted without consent; the declarations generally attempted to furnish appropriate grounds for discharge. Adonijah Marvin of Otsego County, New York, submitted one such record to military authorities on May 4, 1813, verifying that his son, William B. Marvin, enlisted in Capt. John McIntosh's Company, Light Artillery, while "still a minor under the age of twenty one years." The elder Marvin asserted his son was now "desirous of obtaining his discharge from his said enlistment." Mary Sharp of New York City likewise attested to the illegal enlistment of her son, Thomas Sharp, who joined the First Light Artillery on September 26, 1813 "without the knowledge, consent, or approbation of this deponent." Further justifying Thomas's release from service, Mary apparently cited personal hardship, noting the "generally infirm and disabled" condition of her husband, William Sharp.23

General Records Provide Look At American Army as a Whole

Another affidavit verifying the paternal relationship of a deceased soldier came from the selectmen or town officials of Wiscasset in Lincoln County, Massachusetts (then a part of the District of Maine). Submitted by William Nickels, John Merrill, Jr., and Warren Rice, the deposition confirmed that Wiscasset resident John J. Foye was "the Father & by law the legal representative" of Jacob Foye, a member of Capt. Elijah Hall's Company, 45th U.S. Infantry, who "lately died a soldier in the service of the United States" (he succumbed to a fever at Burlington, Vermont, on September 30, 1814). Also asserting Jacob Foye "was a minor and unmarried" at the time of his death, the deponents most likely rendered the affidavit in order to facilitate the disbursement of the deceased soldier's remaining military pay ($39.73), retained bounty ($74), and 160 acres of bounty land to his appropriate legal heir.24

Records of a more general nature also document information about multiple soldiers. A number of affidavits relating to the Battle of Lake Champlain, for example, identify various Regular Army soldiers who served with the American fleet. Most of the affidavits concern extra pay due for naval service, such as the account submitted to Paymaster General Robert Brem by attorney Charles P. Curtis after the war. Writing on behalf of 36 former soldiers of the 15th U.S. Infantry who "acted as marines on board of Commodore W. Donophy['s] U.S. Fleet in the action of the 11th September 1814," Curtis requested "payment of three months extra pay," the money being due in accordance with a postwar resolution of Congress allowing such compensation for soldiers who served in other military branches. Paymaster General Brem readily approved the extra pay on October 23, 1816.25

Several lists of dead, absent, or discharged men from the 16th U.S. Infantry show the names, dates of service, and balances in pay for deceased soldiers who served during the early part of the war, from July 11 to December 9, 1812. Other lists of men discharged at Fort Mifflin and Province Island Barracks between May 20 and December 31, 1814, concern soldiers who failed to pass muster or inspection. In addition to name, regiment, and dates of enlistment and discharge, the lists identify various reasons why these soldiers proved unfit to serve. Disqualifications ranged from natural infirmities such as old age, blindness, deafness, and idiocy, to specific ailments including swollen legs, ruptures, rheumatism, "incurrable siphilis," epilepsy, and "lameness occasioned by habitual intoxication."26 Other assorted lists include men discharged from Governor's Island, August 10, 1813; recruits of the Sixth U.S. Infantry discharged at Fort Columbus, 1813; and lists of sick men at Greenbush Cantonment, April 26, 1813, and the General Military Hospital, New York, February 14, 1814.

A few general payroll lists for discharged men provide additional information not mentioned in the individual pay vouchers and subsistence accounts. The payrolls identify soldiers by name; unit (company and regiment); rank; date and place of discharge; place of residence; term of service; additional pay and bounty due; and commencement of financial settlement. Specific travel allowances calculated the distance to return home, the rate or miles of travel per day, the number of days traveled, and the pay rate per day. The lists also indicated the number of rations issued, the cost of rations per day, and the total amount of subsistence allowed for the soldier to return home. After William Towson was discharged on June 12, 1815, he received six dollars to journey 600 miles from Buffalo to Baltimore (20 miles per day for 30 days at 20 cents per day). He also received $5.10 for 30 rations (1 ration per day at 17 cents per ration), along with back pay ($46.20) and additional bounty ($18.00), for a total allowance of $75.30.27

Related Military Records Accessible in Other Record Groups at NARA

Other records are available at the National Archives to research military service in the Regular Army during the War of 1812. In RG 94, the Registers of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798–1914 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233), provide the principal source of information. The registers from 1798 to 1815 identify the name of the enlistee, his age, place of birth, physical description, the date he enlisted, regimental assignment, and the name of the recruiting officer. They also include the date and place of discharge and other notations such as where the soldier's unit was stationed. The registers sometimes include notes about state militia officers, Regular Army officers, and U.S. Military Academy cadets. The registers are arranged by year, with enlistment entries cataloged roughly alphabetically by the first letter of the soldier's surname, then by first letter of the given name, and then roughly chronological by date of enlistment.28

Enlistment papers for 1798 to October 31, 1912 (Entry 91) consist of two files of recruitment records for individual soldiers in the Regular Army. The earlier file covers 1798 to July 14, 1894, but the majority of the papers relate to post–War of 1812 service. Arranged alphabetically by surname, the enlistment papers generally show the name of the soldier, age, occupation, a personal description, place and date of enlistment, recruiting officer, and regimental assignment. Certificates of disability (Entry 95), issued by Army surgeons recommending discharges for invalid soldiers, contain much of the same information, such as name, rank, military unit, and enlistment information, and also personal data including age, place of birth, a physical description, and statements relating to specific infirmities. Arranged into several files, including one for the War of 1812, the certificates of disability are otherwise unorganized and difficult to use.29

Regimental records for Regular Army units that served during the War of 1812 are located in Record Group 98, Records of United States Army Commands, 1784–1821. Orderly books (containing handwritten transcriptions of orders issued and received) and company books are available for most units, including the First through Third Artillery (1812–1814), the Corps of Artillery (1814–1821), the Regiment of Light Dragoons (1812–1815), the First through 46th U.S. Infantry, and the First and Third Rifleman Regiments. The company books usually contained descriptive inventories of enlisted men, lists of officers, and rosters of men separated from service by transfer, death and wounds, discharge, and desertion. Some regiments maintained additional records such as morning reports, monthly returns, letters sent and received by headquarters, accounts of clothing issued to troops, inspection returns, and muster rolls. One unit, the Second U.S. Infantry, also kept a ledger of discharges, deaths, and desertions (1811–1814).30

Surrendered bounty land warrant files are in Record Group 49, Records of the Bureau of Land Management, and are usually arranged by the year of the act of Congress that authorized the warrant, then by the number of acres, and finally the warrant number. These records document the surrender of the bounty land warrant for a patent for federal land in the public domain. While many veterans or their heirs sold the warrants to unrelated third parties, these files nonetheless provide evidence of the final disposition of the warrants. Some bounty land warrants were issued at the time of the war, and those issued under the acts of Congress of 1812, 1814, and 1842 are indexed in National Archives Microfilm Publication M848, War of 1812 Military Bounty Land Warrants, 1815–1858 (14 rolls), and others issued under the acts of 1812, 1850, and 1855 are indexed in National Archives Microfilm Publication M313, Index to War of 1812 Pension Application Files (102 rolls).31

In addition, there are many bounty land warrant application files based on War of 1812 service in Record Group 15, Records of the Veterans Administration, and these are arranged alphabetically by name. The veteran's application provides evidence of his military service to prove his eligibility for a warrant. Some applications were made by the veteran's widow, minor children, or occasionally, parent, and in these cases, the proof of marriage or parentage was required. Researchers should request a search of the bounty land warrant application files even if an entry for the soldier is not found in either M848 or M313. Congress first authorized pensions for War of 1812 veterans in 1871 and to their widows in 1878, and these pension files are also in Record Group 15.

Although the War Department normally did not retain certificates of discharge—either for the Regular Army or the volunteer services—the availability of such records for a portion of U.S. Army veterans from the War of 1812 adds much substance to the details of their service. Providing a litany of personal information as well as a record of enlistment, financial compensation for military service, and reasons why service terminated, the discharge certificates offer a concise glimpse into a soldier's wartime service. In a few fortunate instances, extra or unexpected details—including birth and marriage information and parental relationships—occur in these records as well, enhancing the value of the discharges and related records as useful tools to document the lives of a select group of soldiers from the War of 1812.

John P. Deeben is a genealogy archives specialist in the Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. He earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and the Pennsylvania State University.

Claire Prechtel-Kluskens is a projects archivist in the Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. She specializes in records of high genealogical value and writes and lectures frequently.

Notes

1 Dragoons originally served as mounted infantry, riding on horseback for offensive maneuvers and standing on foot for defense. By the 18th century, however, they had generally evolved into conventional light cavalry, but their principal weapons still included a carbine (short-barreled musket) as well as a sabre.

2 Discharge certificate for Pvt. John Warring, Corps of Light Dragoons, March 21, 1815; Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records Relating to the Discharge of Soldiers from the Regular Army, 1792–1815 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1856, roll 5); Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, Record Group 94 (RG 94); National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB).

3 Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records Relating to the Discharge of Soldiers from the Regular Army, 1792–1815, Descriptive Pamphlet M1856 (Washington, DC: National Institute on Genealogical Research Alumni Association and National Archives and Records Administration, 2003), p. 2. See also Claire Prechtel-Kluskens, "War of 1812 Discharge Certificates," NGS NewsMagazine 31:3 (July–September 2005): 29.

4 Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates, p. 1.

5 Ibid; Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), pp. 76–77.

6 Ibid.

7 Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates, p. 1.

8 Lucille H. Pendell and Elizabeth Bethel, comps., Preliminary Inventory 17, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Adjutant General's Office (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1949), p. 11.

9 Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates, p. 3.

10 Discharge certificate for Gabriel Caves, Capt. John B. Long's Co., 39th U.S. Infantry; Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records (M1856, roll 4), RG 94, NAB.

11 Descriptive list for William T. Smith, 16th U.S. Infantry; Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records (M1856, roll 2), RG 94, NAB.

12 Descriptive lists for Stephen McCarrier and Samuel Barnes, 14th U.S. Infantry; in Ibid; Discharge certificate for Thomas Webster, Corps of Artillery, July 9, 1814 (M1856, roll 6).

13 Certificates of death for Henry Carman, 2nd U.S. Artillery, April 1, 1814, and William Peters, 2nd U.S. Artillery, December 21, 1813 (M1856, roll 6).

14 Certificate of death for William Hutchins, 21st U.S. Infantry, March 14, 1815 (M1856, roll 2).

15 Pay vouchers for Pleasant Hazelwood, 2nd Regiment Light Dragoons, April 23, 1813, and Henry Carman, 2nd U.S. Artillery, November 3, 1815 (M1856, rolls 5–6).

16 Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates, p. 5.

17 Recommendation for discharge, Elisha Harrington, 2nd U.S. Light Dragoons, and furlough for George Shippey, Light Dragoons, March 28, 1815, Discharge Certificates and Miscellaneous Records (M1856, roll 5), RG 94, NAB.

18 Enlistment paper for Andrew McMillen, 23rd Infantry, May 17, 1812 (M1856, roll 2).

19 Substitute certificate for John Miller, 1st U.S. Light Dragoons, January 9, 1814 (M1856, roll 5).

20 Subsistence account for 2nd Lt. Rodolphus Simons, 23rd U.S. Infantry, March 2, 1814 (M1856, roll 2).

21 Affidavit of Thomas Briggs, 9th U.S. Infantry, regarding the nativity of his son, William Briggs, 9th U.S. Infantry, June 23, 1814 (M1856, roll 1).

22Marriage certificates for Henry Carman, 2nd U.S. Artillery, and John Uber, 15th U.S. Infantry (M1856, rolls 2, 6).

23 Affidavits of Adonijah Marvin, May 4, 1813, and Mary Sharp, November 16, 1813 (M1856, roll 6).

24 Affidavit verifying the minority of Jacob Foye, 45th U.S. Infantry (M1856, roll 5).

25 Paymaster General Robert Brem to Charles P. Curtis, October 23, 1816, Affidavits Relating to Service on Lake Champlain, 1814 (M1856, roll 1).

26 Lists of Dead and Absent Men, and Lists of Men Discharged at Fort Mifflin and Province Island Barracks, ibid.

27 Payrolls of Discharge Men, ibid.

28 Prechtel-Kluskens, Discharge Certificates, pp. 7–8.

29 Pendell and Bethel, Preliminary Inventory 17, pp. 28–29.

30 Maizie Johnson and Sarah Powell, Preliminary Inventory NM-64, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of United States Army Commands, 1784–1821 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1966), pp. 22–55.

31 For more information, see Kenneth Hawkins, reference Information Paper 114Research in the Land Entry Files of the General Land Office (Record Group 49) (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, rev. 2009).