Nazis Soaring over Washington?

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3

By Chas Downs

In the years shortly before America’s involvement in World War II, a graceful, cream-colored glider could often be seen soaring above Washington, D.C., and vicinity.

Since gliding was a popular sport in the 1930s, a glider was not an unfamiliar sight, except that this one flaunted a red tail bank with a Nazi swastika in the center.

This is the story behind that glider and its pilot.

After World War I, the German government encouraged the sport of gliding as a way to train pilots and participate in aviation, since the German aircraft industry was severely limited by the Treaty of Versailles. After their assumption of power in 1933, the Nazis enthusiastically continued this support as a way to make Germans “air-minded” and rebuild Germany into an air power. It was also a source of national pride, given that Germany had become a world leader in the sport of gliding and soaring, and German pilots held many world records.

One of the most renowned of these record-setting pilots was Peter Riedel. Born in 1905, Riedel studied engineering and became a commercial pilot, worked at the Meteorological Institute of Röhn-Rositten Company, and toured South America with the institute’s head, Dr. Walter Georgii, to promote the sport of gliding.

After working as a pilot for Lufthansa, and briefly undergoing reserve training in the German military, Riedel took a job with the Colombian airline SPACDA. He claimed to find life in the Third Reich to be too confining and sought broader horizons. In any case, he had become romantically involved with a married Argentinian woman and crossed the Atlantic to be closer to her. In 1937, Riedel, sponsored by the German Aero Club, competed at the Soaring Society of America national competition. Flying a DFS Sperber glider, with German registration and swastika national markings, he won the Bendix gold trophy for the longest distance flight, 133 miles from Elmira, New York, to Elizabeth, Pennsylvania.

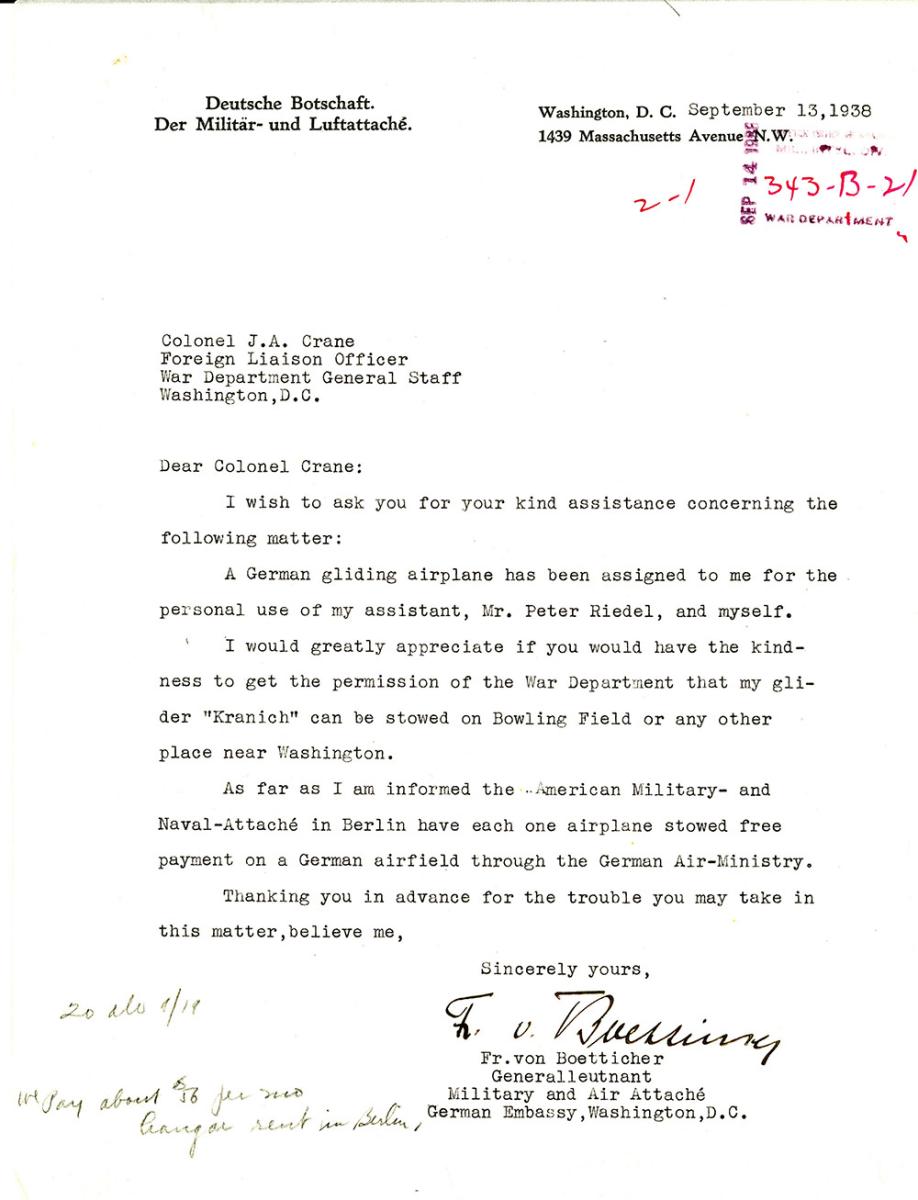

While at Elimira, Riedel met the German military attaché in Washington, D.C., Col. Friedrich von Boetticher, who was impressed enough with Riedel to offer him a job as technical assistant for aviation matters at the German embassy in Washington. At first Riedel refused, but he subsequently accepted the position in order to stay in America. After a replacement for his airline job arrived, he then traveled back to Germany to be vetted by the Air Ministry.

In Berlin, he was interviewed by the Abwehr, the German military intelligence agency headed by Adm. Wilhelm Canaris. The Abwehr played by its own rules and was distrusted by other German military and intelligence organizations. While later in life Riedel denied ever being a Nazi or ever having been an NSDAP member, records show that he had joined the Nazi Party twice, in 1931 and 1933, letting his membership lapse both times. According to State Department sources, Riedel was by all appearances a confirmed Nazi while in the United States, but his affiliations seem to have been more of convenience than conviction. He was probably too much of a free spirit to be a good party man.

The Swastika over Washington: Crossing the Mall before Landing

Before starting his duties at the German embassy in Washington, Riedel stopped by Elmira to participate in the 1938 American national soaring competition under the auspices of the German Aero Club, his two-seat DSF Kranich glider again carried full German national markings, including a red band with a swastika on its rudder. Riedel’s ground crewman also briefly displayed a Nazi flag, which drew unfavorable attention to his glider’s Nazi markings.

Reflecting a changed political climate since 1937, the swastika insignia caused Riedel considerable embarrassment in 1938. Registered in Germany in order to avoid U.S. import duties, his glider displayed the Nazi markings that were required on all German military and civil aircraft. Once it became known he was working for the German embassy, however, this explanation did not convince many of Riedel’s acquaintances, who began to assume he was a confirmed Nazi.

The 1938 soaring competition had fewer but more experienced pilots than in 1937. Riedel took an early lead with successful flights to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Wilmington, Delaware. He was determined to do something spectacular to publicize the sport of soaring—fly from Elmira to Washington, D.C. Such a feat would also win a thousand-dollar prize.

On the morning of July 3, after determining that conditions would be favorable, Riedel was launched in his Kranich at 10:30 a.m. He soon found a strong thermal and reached an altitude of 6,000 feet, high enough to clear the 3,000-foot ridges he was crossing, but he often needed to fly on instruments through cloud formations. By 5 p.m., Riedel had reached Baltimore, but the strong thermals that had gotten that far were failing. Despite his knowledge and skill, he was losing altitude too quickly.

Pulled toward the ground by the cooling air, he spotted the familiar environs of Washington, D.C. He passed over College Park Airport, hoping that the sun-warmed streets of Washington would give him just enough lift to make it to Hoover Airport (now Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport), just on the other side of the Potomac River in Virginia. He crossed the Mall and skimmed 200 feet above the Washington Monument.

Just when he no longer needed it, he found another thermal, circling to gain altitude in order to do some aerobatic turns and loops before landing at Hoover Airport at 6:20 p.m. In this remarkable flight, Riedel set a national and international distance record of 227 miles for a flight to a predeclared target.

After returning to Elmira, Riedel made another long-distance flight, 196 miles to Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York. As he had been in 1937, Riedel was the highest scoring pilot in the 1938 Elmira competition and would have been U.S. national champion but for the fact that he was not an American citizen.

Nazi Leaders Reject Warnings about U.S. Aviation Industry

At the height of his gliding career, Riedel’s fame, training, connections, and background were all helpful to him in carrying out his new duties at the German embassy, which were to collect, organize, and evaluate information on American military aviation.

Youthful and convivial, Riedel did not get along well with his new boss, whom he found stiff, humorless, and pompous. On his part, von Boetticher, who was vehemently opposed to German diplomatic personnel engaging in espionage activities in the United States, may have suspected that Riedel had a relationship with the Abwehr.

Riedel himself claims to have used no undercover agents but extrapolated quite accurate statistics on American aviation industry production and expansion from published sources, both governmental and commercial. He managed to tour various American aircraft manufacturing facilities in person, but most of his efforts were directed at reviewing and analyzing the massive files of clippings and publications readily available from the American media.

Once World War II broke out in Europe in September 1939, Riedel’s task was to determine when American aircraft production would be substantial enough to adversely affect the military operations of the Axis powers. He predicted that by 1942 American-built aircraft could be supplied to the Allies in such quantity that they would dominate the war in the air. Riedel’s superiors at the embassy did not fully support his reporting and estimates even though they were reasonably accurate. Since they contradicted the Nazis’ unrealistic but unquestioned views of America, Riedel’s projections were ignored or dismissed by the German leaders in Berlin.

Riedel Flies for Fun, Takes Friends on Rides

But Riedel still lived to fly.

The German embassy kept a two-seat Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug (D.F.S.) G-27 Kranich glider at College Park Airport, in suburban Maryland, for his use. In an era when aeronautical feats were an almost daily news staple, Riedel and his glider received their share of attention.

A September 26, 1938, article in the Washington Post described how Riedel had taken off from College Park Airport to watch the President’s Cup regatta. After staying aloft for three hours, he was forced to land at nearby Hoover Airport because of cool air currents above the Potomac and had to be towed back to College Park.

“It was just for fun,” Riedel is quoted as saying. “When I haven’t flown for 14 days, I feel bad.”

Since the Kranich held two, he was able to give glider rides to friends and colleagues. Riedel also participated in various soaring events and demonstrations around the United States, including the 1938 Cleveland Air Races, where his longtime friend and fellow glider pilot Hannah Reitsch dazzled the crowds with her acrobatics.

Riedel normally based his glider at College Park Airport, although he flew out of other area airports, including Hybla Valley in Virginia. When it was not in use, he was allowed to store his Kranich at the U.S. Army Air Corps’s Bolling Field, in southwest Washington, D.C.

In 1939, Congress authorized the War Department to provide supplies and services to aircraft used by accredited foreign military attachés, so the U.S. Army ended up defraying mush of the expense of maintaining Riedel’s glider.

Now Married, Riedel is FBI Target; An Assault Incident Is Disregarded

After war broke out in Europe, German diplomats fell under greater scrutiny. On November 11, 1939, Riedel was involved in an “alley argument,” which became an international incident and generated stories in the Washington papers.

This incident began innocently enough, when Riedel borrowed a friend’s Buick automobile in order to retrieve his glider trailer from Skyline Drive in Virginia. The Buick was housed in a garage in Northeast Washington, D.C. While picking up the car, Riedel inadvertently parked on a neighbor’s flower bed. The neighbor, an auto mechanic and ex-boxer named Frank Werner, became enraged and assaulted Riedel, leaving him bruised and bloody. Police eventually arrived but did not issue any citations since all those involved gave conflicting stories.

Both parties were summoned to the assistant district attorney’s office the next day, but Riedl never appeared, probably because the German embassy was not contacted through proper State Department channels, and the embassy did not want him to appear in any case. Since no complaint was filed against Werner, he was never charged.

The German embassy did lodge a formal protest of the “incident” with the State Department. Dr. Karl Resenberg, first secretary of the German embassy, was quoted as saying, “We do not consider the affair a personal controversy between Riedel and Werner, but rather an issue between two governments.”

In any event, the State Department turned it over to the Justice Department, which quietly closed the case.

In 1940, Riedel was promoted from technical assistant to assistant air attaché, with an increase in salary and status. His personal life also underwent a major adjustment. Riedel had taken up horseback riding as a diversion, and on one of his rides in Rock Creek Park, he met and fell in love with a beautiful American of German descent, Helen Kluge, who worked as an art teacher in the District of Columbia public school.

Riedel met resistance from von Boetticher when he requested permission to marry Helen. After Berlin officially approved the match, the two married in July 1941. Von Boetticher’s initial disapproval then evaporated, and he warmed to the relationship, arranging for a lavish reception at the embassy.

Leaving on a cross-country trip for the honeymoon, the newly married Riedels were followed by FBI agents. After some initial antagonism, they and the agents became solicitous of one another. Once, Riedel waited for the G-men, as FBI agents were known in the slang of the day, to catch up when they were delayed by heavy traffic, and later, the FBI agents informed the Riedels when they had missed the turn to their destination.

In 1940, an unwanted burst of notoriety for German diplomats in America only indirectly affected Riedel. Shot down over England and captured, the Swiss-born Luftwaffe ace Baron Franz von Werra escaped his guards while en route to a POW camp in Canada, crossed the United States, and turned up at the German embassy in Washington in January 1941.

Determined to get back to Germany, the flamboyant von Werra made life difficult for the German ambassador and for von Boetticher. Riedel finally took von Werra aside and explained how he could covertly enter Mexico, then travel to South American, and from there fly back to Europe.

Von Werra followed Riedel’s advice and successfully made his way back to Germany in April 1941. He returned to active service, only to die when the engine of his new Bf-109F failed in a routine patrol over the North Sea on October 25, 1941.

As War Begins, Riedel Returns to German, Is Later Betrayed

Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hitler declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941. Subsequently, U.S. authorities rounded up and interned German diplomatic personnel and sent them to the Greenbriar resort in West Virginia for safe-keeping. Riedel’s glider became U.S. property and apparently was allowed to “rot to pieces” at College Park Airport, according to a history of the Skyline Soaring Club. U.S. authorities also confiscated a trunk full of 8mm movies Riedel had taken while flying his glider around the country. German and Italian diplomats were put aboard the old Swedish liner S.S. Drottingholm for repatriation. It sailed from New York on May 7, 1942, and arrived in Lisbon on May 16. The Riedels arrived in Frankfurt-am-Main on May 25, 1942.

Helen Riedel, as the American wife of an Axis diplomat, made the difficult choice to accompany her husband back to Germany. There she contracted a lung disease and eventually had to go to a sanitarium in Switzerland for her health. While separated from his wife, Riedel, an inveterate womanizer, engaged in several romantic relationships with other women. After being debriefed by German authorities, Riedel began working for the German Air Ministry. While there he tried to convince the Nazi leaders in person of the growing power of the American aircraft industry, again without success.

Riedel managed to obtain an assignment to Sweden as an air attaché, all the while working for the Abwehr. Disillusioned by official indifference to his warnings about the American aircraft production and by published reports of Nazi atrocities, he tried to contact Office of Strategic Services chief Bill Donovan, whom he had met in New York before the war, but the OSS was uninterested in him.

Betrayed by German authorities by a confidant of his current lover and recalled to Germany, Riedel instead went into hiding in Sweden, with the help of his female friends. After the war, he fled Sweden only to be imprisoned by the French in Casablanca before escaping on a yacht to Venezuela. There he was joined by his faithful wife, Helen, who had reclaimed her American citizenship after returning to the United States from Switzerland. Leaving Venezuela, they went to Canada, and when Riedel was expelled by the Canadians, to South Africa.

Finally able to return to the United States in 1955, he worked as an engineer for Trans World Airlines and Pan American World Airways. In retirement, he wrote a three-volume history of the prewar German gliding movement and collaborated with fellow gliding enthusiast Martin Simons on his biography. Riedel died in Ardmore, Oklahoma, in 1998. His devoted wife, Helen, died in a Texas retirement home on December 11, 2000.

Riedel was a larger-than-life character who became a world-renown glider pilot, setting many German, American, and international records. Nominally a Nazi, he joined the party largely out of self-interest and probably denied his membership for the same reason. The intelligence that he gathered while in Washington certainly could have proved valuable to the Nazi leadership if they had acted on it. As for his adventures and romances, Riedel certainly told a good story, which he was not above embellishing.

Probably the greatest glider pilot of her time, he ranks among aviation’s most outstanding pilots.

One thing is undeniable: Peter Riedel really knew how to fly his Kranich.

Chas Downs is an artist, researcher, and archivist living in Howard County, Maryland, with his wife and cat. Retired after a career with the National Archives, he is an active NARA volunteer at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

Note on Sources

At the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State, Decimal Files covering the years 1939, 1940, and 1941, contain several references to Peter Riedel. The most voluminous records, concerning his altercation with Frank Werner, can be found in the 1930–1939 Decimal Files, 701-6211-1110. Other references are in 701-6211-1031 and 1042, 811.7961/328, and 811.7966 Sca 2/415. For 1940 and after, references to Riedel appear in Decimal Files 701-6111/1134, 701.6219/54, 701.62701.6211-111011/1134, 800.202 11/767, and 776, and 811.7961/1439, 1501, 1541, 1558, and 1658.

OSS records relating to Riedel can be found in Record Group 226, Records of the Office of Strategic Services, Classified Sources and Methods Files, “Withdrawn Records” (Entry A-1, 215), File W21062; Records of Other Field Bases, Field Station Files—Stockholm-X-2-PTS-2-7 (Entry 125), Folder 2; and Field Station Files—Stockholm-X-2-PTS-5 (Entry 125A), Folder 367. The latter folder contains a good photograph of Riedel standing next to the tail of his glider.

Several references to Riedel and his activities as air attaché may be found in Record Group 165, Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, G-2 (Military Intelligence Division), Foreign Liaison Branch, “Attaché Military, German in Washington"; see the Index, and especially the following files: 343-B-21, 343-D-3, and 343-W-162.

Several articles concerning Riedel appeared in the Washington Post. A number relate to his accomplishments as a glider pilot: July 11–12, 1937, July 5, 1938, and September 25, 1938. Stories on December 4 and 5, 1939, cover his “scrape” with Werner and its aftermath. Riedel’s alley confrontation is also mentioned in a commentary column “Over the Coffee,” by Harlan Miller, December 13 and 20, 1939. Several articles about von Werra appeared in the Washington Post during 1941, including one with a comment by Riedel, April 23, 1941. The fate of Riedel’s Kranich glider is mentioned by Jim Kellett in “Skyline Soaring Club in the Twentieth Century,” January 2000.

A series of three articles about the Riedels by Mike McCormick appeared in the Terre Haute Tribune Star, June 18, July 7, and July 14, 2007; “Historical Perspectives: Pilot under vigilant eye of FBI made trip to Terre Haute”; “Historical Perspective: The continued story of Peter and Helen Riedel”; and “The story of Peter and Helen Riedel, part III.” Helen Riedel was a Terre Haute native, and she and Peter visited her relatives there when they were being tailed by the FBI.

Not readily available in the United States is Martin Simons’s German Air Attaché: The Thrilling Story of German Ace Pilot and Wartime Diplomat Peter Riedel (Ramsbury, UK: Airlife, 1997). Simons, a British author and glider pilot, based this book on a typescript written by Riedel and tape recordings of their conversations, as well as other material provided by Riedel. Written in the first person, it reads as if it were Riedel’s autobiography and is the source of information for most secondary works on Riedel.

A scholarly biography of the German military attaché in Washington, Alfred M. Beck’s Hitler’s Ambivalent Attaché: Lt. Gen. Friedrich von Boetticher in America, 1933–1941 (Washington DC: Potomac Books, 2005), puts Riedel’s activities in the context of his position in the German embassy and with the German government in Berlin, as well as sketching out the diplomatic atmosphere of prewar Washington, D.C. A former Army historian, Beck had access to some of Riedel’s papers and photographs provided by the executor of his estate.

A curator at the National Air and Space Museum, Von Hardesty puts Riedel into a different context, that of outstanding pilots and historic flights. Von Hardesty, Great Aviators and Epic Flights (Southport, CT: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, Inc., 2002). In the chapter “Riedel: Soaring to Washington,” pp. 142–153, of this well-illustrated coffee-table size book, Hardesty provides a detailed account of Riedel’s 1938 flight from Elimira, New York, to Washington, D.C., which closely follows Riedel’s own description in Martin Simons’s book. While unfootnoted, this account was apparently based on Riedel estate archival materials currently in Hardesty’s possession.

An entertaining book based on Luftwaffe ace von Werra’s exploits, The One That Got Away, by Kendal Burt and James Leasor, came out in 1956. A movie of the same name, starring Hardy Kruger, appeared in the next year.