Hit the Road, Jack!

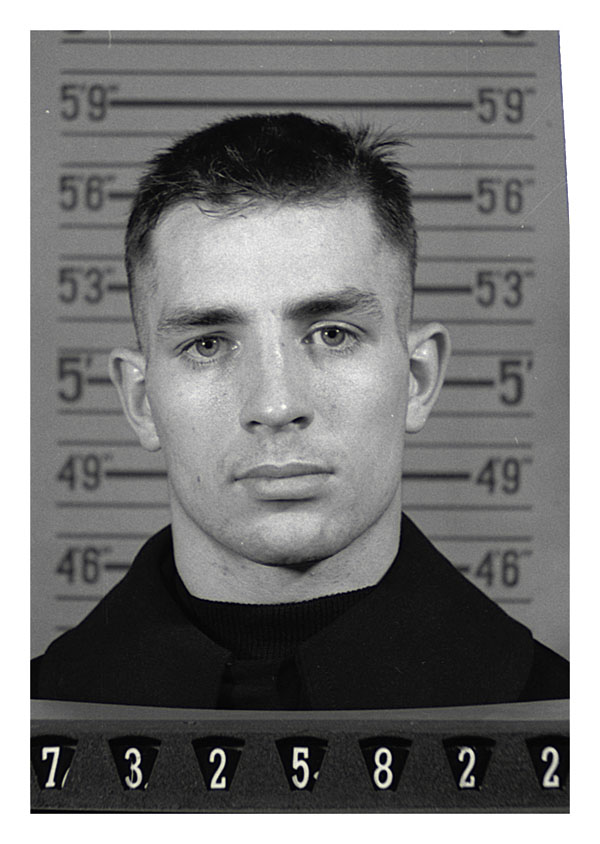

Kerouac Enlisted in the U.S. Navy But Was Found “Unfit for Service”

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3

By Miriam Kleiman

Jack Kerouac—American counterculture hero, king of the Beats, and author of On the Road—was a Navy military recruit who failed boot camp.

While some Kerouac biographies mention his military experience, the extent of it was unknown until 2005, when the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, made it public. It was part of the release of military files of about 3,000 prominent Americans who had been deceased for at least 10 years.

Kerouac enlisted in the U.S. Navy Reserve (then called the U.S. Naval Reserve) during World War II. But he never left the United States, never saw action, and never even completed basic training.

In all, he lasted 10 days of boot camp before being referred first to the sick bay and then the psychiatric ward for 67 days. Kerouac's extensive medical and psychiatric evaluations produced both a large file and the conclusion that he was "unfit for service."

The qualities that made On the Road a huge success and Kerouac a powerful storyteller, guide, and literary icon are the same ones that rendered him remarkably unsuitable for the military: independence, creativity, impulsivity, sensuality, and recklessness.

On the Road can be viewed as a giant extended shore leave. Indeed, the first of his cross-country trips later depicted in On the Roadtook place in 1947—just a few years after his failed military attempt.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the writing of On the Road. Although the book was published in 1957, Kerouac produced the legendary 120-foot continuous scroll in April 1951 by taping long sheets of tracing paper together so he could type without interruption.

Columbia Beckons Kerouac with a Football Scholarship

Kerouac's military personnel file is half an inch thick—nearly 150 pages—and details a troubled soldier-in-training who collapsed under military discipline and structure. The doctors' findings identify and foreshadow the carefree, reckless, impulsive wanderlust that characterizes Kerouac's writing.

This file presents both a very gifted and a very disturbed young man. While his military record includes extensive mental examinations, it also includes stellar letters of recommendation. Kerouac attended Columbia University on a football scholarship. There, he was praised by teachers and professors for his "unusual brilliance," loyalty, citizenship, character, and "good breeding."

Born and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Kerouac completed high school there, then spent an additional year of high school at Horace Mann Prep in New York on a full scholarship before continuing to Columbia University. He completed his freshman year "with failure only in chemistry." He quit college to enter the merchant marine but left after three months.

At the request of his football coach, Kerouac returned to Columbia in October 1942, but he dropped out a month later. In a November 1942 letter, he told a friend he was unhappy at Columbia and sought greater meaning at a historic time:

I am wasting my money and my health here at Columbia . . . it's been one huge debauchery. . . . I am more interested in the pith of our great times than in dissecting "Romeo and Juliet." . . . These are stirring, magnificent times. . . . I am not sorry for having returned to Columbia, for I have experienced one terrific month here. I had a gay, a mad, a magnificent time of it. But I believe I want to go back to sea . . . for the money, for the leisure and study, for the heart-rending romance, and for the pith of the moment.

In an unmailed letter to a girlfriend in July 1942, Kerouac outlined noble reasons for enlisting:

For one thing, I wish to take part in the war, not because I want to kill anyone, but for a reason directly opposed to killing—the Brotherhood. To be with my American brother, for that matter, my Russian brothers; for their danger to be my danger; to speak to them quietly, perhaps at dawn, in Arctic mists; to know them, and for them to know myself. . . . I want to return to college with a feeling that I am a brother of the earth, to know that I am not snug and smug in my little universe.

On December 8, 1942, one year and one day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kerouac enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve for a four-year term of duty.

"Fine Moral Character and Good Breeding"

Kerouac's military personnel file includes glowing letters of recommendation. His school record was "one of unusual brilliance both scholastically and athletically," gushed Lowell High School Master Joseph G. Pyne. Kerouac was "an ideal pupil with an unusual combination of brilliance and athletic ability," Pyne added.

And he was an overachiever—earning 88 credits when only 70 were required for graduation.

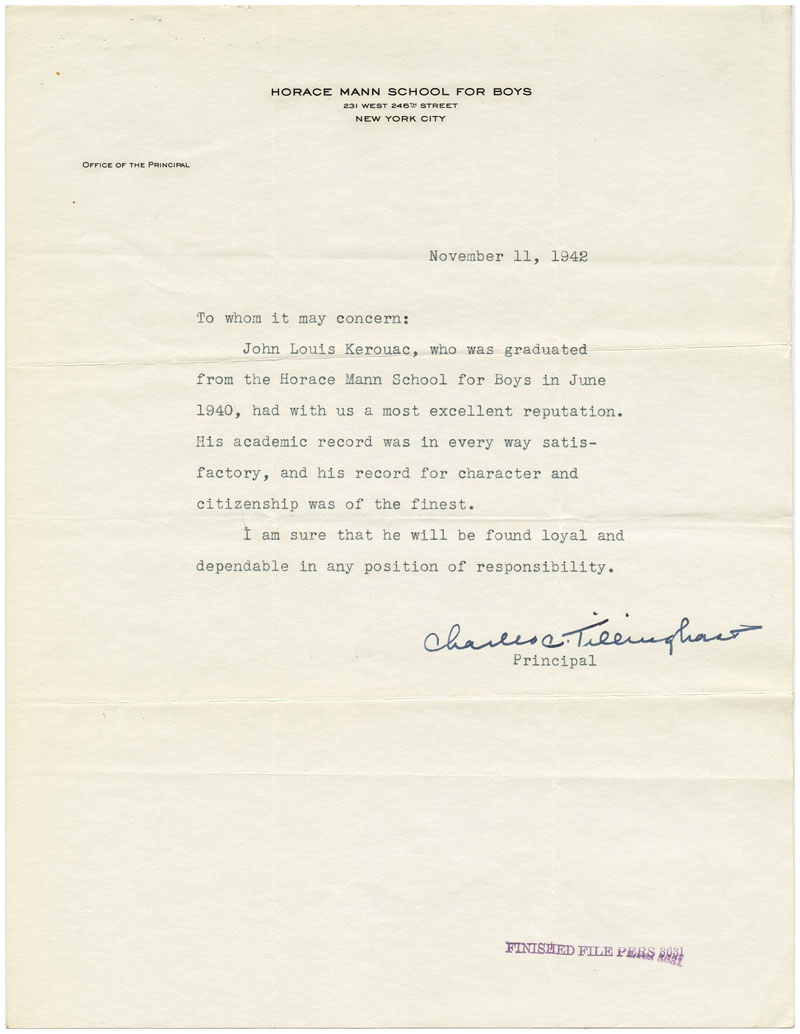

Horace Mann Prep principal Charles C. Tillinghast praised Kerouac's reputation in a letter of recommendation written in November, 1942:

John Louis Kerouac . . . had with us a most excellent reputation. His academic record was in every way satisfactory, and his record for character and citizenship was of the finest.

I am sure that he will be found loyal and dependable in any position of responsibility.

Kerouac received an "unqualified endorsement" from his French instructor at Columbia the same month:

I found him . . . extremely capable, possessed of a refreshingly alert intellectual capacity and an ability to think independently. Mr. Kerouac adds to these qualifications a distinctly engaging personality which makes him win friends easily. He is a young man of fine moral character and good breeding. His self-reliance and resourcefulness have been demonstrated by his ability to fend for himself, and give evidence of the qualities of leadership you are undoubtedly seeking among your candidates.

Before reporting to basic training, Kerouac requested a transfer—hoping to upgrade to "Naval Aviation Cadet" (Navy pilot) instead of "Apprentice Seaman." He appeared before the Naval Aviation Cadet Selection Board in Boston for a series of examinations.

Despite testing well in most subjects (he received a 91 percent "general classification," 99 percent in spelling, and 95 percent in English), his transfer was rejected. The board found Kerouac "not temperamentally adapted for transfer." In addition, Kerouac failed overall due to "mechanical inaptitude"—scoring just 23 percent on the mechanical aptitude test.

In his semi-autobiographical novel Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935–46, Kerouac summarized this experience:

I entrain to Boston to the US Naval Air Force place and they roll me around in a chair and ask me if I'm dizzy. "I'm not daffy," says I. But they catch me on the altitude measurement shot. "If you're flying at eighteen thousand feet and the altitude level is on the so and such, what would you do?"

"How the screw should I know?"

So I'm washed out of my college education and assigned to have my hair shaved with the boots at Newport.

Navy Boot Camp Disastrous: "Bored Easily, Lacked Focus"

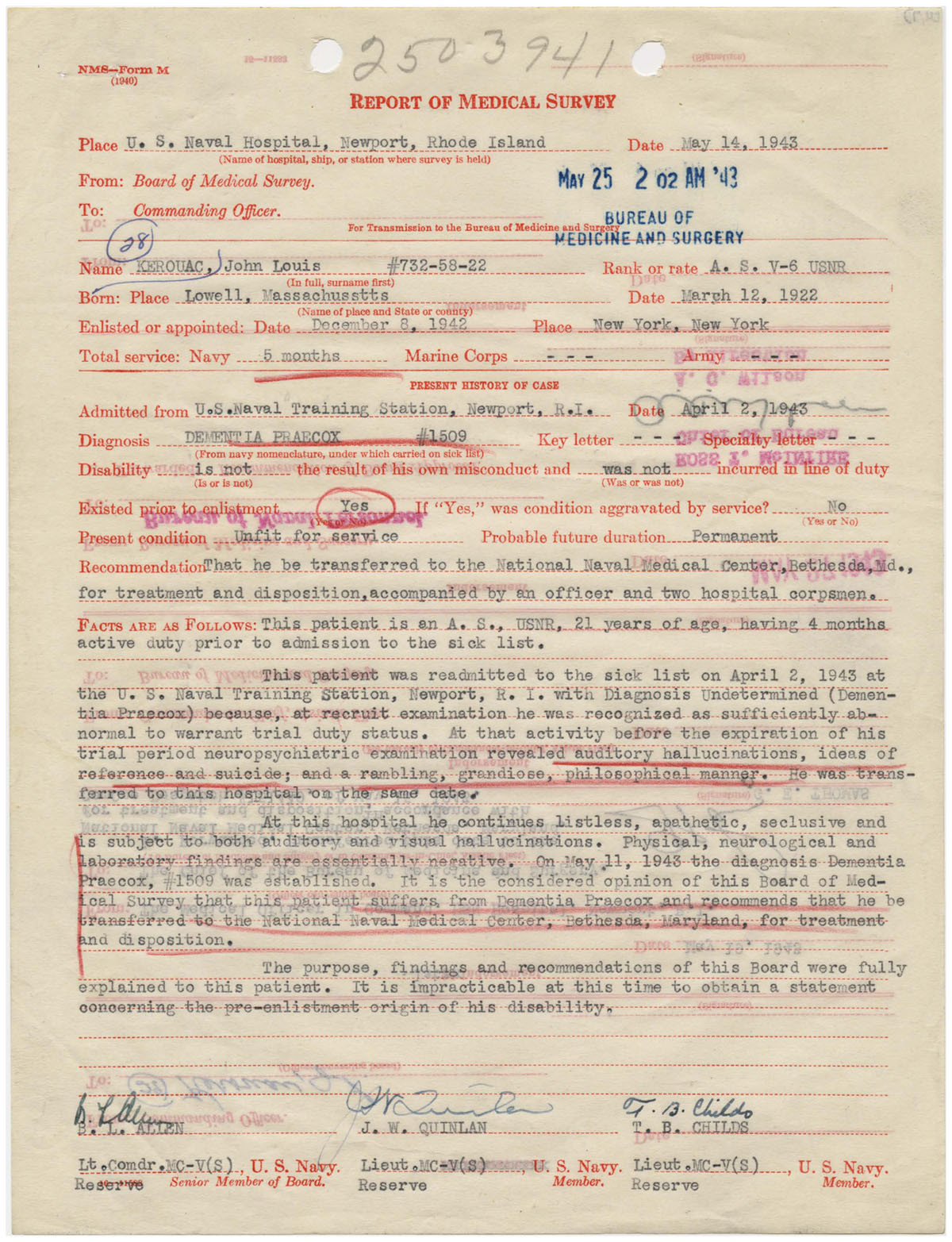

Kerouac reported to the Naval Training Station in Newport, Rhode Island, on February 26, 1943. There were concerns from the start, however; during his initial examination, he was "recognized as sufficiently abnormal to warrant Trial Duty status." The trial period did not go well; Kerouac's boot camp experience was a disaster. After only 10 days of basic training, he was transferred from the Naval Training Station to the Naval Hospital in Newport because he had numerous headaches and "appeared to be restless, apathetic, seclusive [sic]."

In addition, "neuropsychiatric examination disclosed auditory hallucinations, ideas of reference and suicide, and a rambling, grandiose, philosophical manner." Diagnosed with dementia praecox (schizophrenia), Kerouac was sent to the Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland (now the National Naval Medical Center) for further examination.

At the Naval Hospital, doctors questioned Kerouac at length about his family, academic, work, and sexual history. His file contains numerous exchanges between Kerouac and his doctors.

However, his concurrent letters to friends and family offer a different perspective. Kerouac wrote to friends and family while under observation. These letters reflect Kerouac's varying responses to the diagnosis of severe mental illness—reactions ranging from rejecting to accepting, and even embracing and exalting, his condition.

These letters also show that Kerouac seemed to enjoy challenging, leading, and even shocking his doctors. While this behavior may have been a defense mechanism or even denial, Kerouac did seem to have a basic understanding of psychiatry; he details conditions, symptoms and indicators, of mental illness, dementia praecox in particular. Contrasting his medical file with his letters yields insight into Kerouac's psyche at a pivotal time in his life.

Kerouac's psychiatrists astutely determined that his failed military experience resulted from his rejection of authority, order, discipline, and structure.

Not surprisingly, especially given his later adventures, Kerouac hated boot camp due to "the regulation and discipline." His medical history from the Bethesda Naval Hospital notes that he became bored easily and lacked focus. He "impulsively left school because he had nothing further to learn" and "just as precipitously" left numerous jobs "because he felt too stilted."

"Patient believes he quit football for same reason he couldn't get along in Navy, he can't stand regulations, etc." He quit school "because he felt he had gotten all he could from college."

"I was frank with them," Kerouac admitted. "I was in a series of ventures and I knew they'd look them up; like getting fired from jobs and getting out of college."

"I just can't stand it. I like to be by myself"

Initially, Kerouac viewed the psychological testing as "folly" and a "farce." He told his mother that in response to headaches "they diagnosed me with dementia praecox." Kerouac believed he was different, but not mentally ill: "as far as I'm concerned I am nervous; I get nervous in an emotional way but I'm not nervous enough to get a discharge."

He claimed he was exhausted because prior to boot camp he had been writing 16 hours a day, working on the novel The Sea is My Brother, which he called a "gigantic saga" (this novel was first published posthumously).

He did not like basic training at all: "I just can't stand it. I like to be by myself." In an undated letter, Kerouac explained:

[I]t was clearly and simply a matter of maladjustment to military life. On this, the psychiatrist and I seemed to be agreed in silence. I believe that if his queries had ended at that point, my diagnosis would have been psychoneurosis—a convenient conclusion which could have explained any number of idiosyncrasies in a protean personality. . . . I see no reason for being ashamed of my maladjustment.

In Vanity, Kerouac details this maladjustment at length:

Well, I didn't mind the eighteen-year-old kids too much but I did mind the idea that I should be disciplined to death, not to smoke before breakfast, not to do this, that, or thatta . . . and this other business of the admiral and his Friggin Train walking around telling us that the deck should be so clean that we could fry an egg on it, if it was hot enough, just killed me.

[A]nd having to walk guard at night during phony air raids over Newport RI and with fussy lieutenants who were dentists telling you to shut up when you complained they were hurting your teeth. . . .

They came and got me with nets. . . . "You're going to the nut house." "Okay." [S]o they ambulance me to the nut hatch.

Kerouac crystallizes his problem with the Navy in Vanity—lack of independent thought. Responding to questions from Navy doctors, Kerouac explained that he was constitutionally incapable of adhering to Navy discipline:

[I]ndependent thought . . . now go ahead and put me up against a wall and shoot me, but I stand by that or stand by nothing but my toilet bowl, and furthermore, it's not that I refuse Naval discipline, not that I WONT take it, but that I CANNOT. This is about all I have to say about my aberration. Not that I wont, but that I cant.

The Navy sought underlying causes of Kerouac's mental illness. The "family history" section notes that Kerouac "denied familial disease. Mother is nervous and father is emotional." Kerouac wrote to his mother, Gabrielle, on March 30, 1943, and encouraged her to speak candidly with his doctors if they called:

Although I tried to hide it, they found out about my headaches when I went to get aspirins a few times. I guess I wrote too much of my novel before I joined the Navy. Anyway, they've placed me under observation in the hospital, and all I do all day is sit around in the smoking room and smoke. . . .

Well, if I can't make the Navy, I'll try the Merchant Marine school—they're not strict there. . . .

At any rate, I have an idea they're going to call you up about it. They're going to give me a nerve test tomorrow. . . .

I told them about my [car] accident in Vermont, my football injuries & everything, so that if I have anything, they'll discover it. Anyway, try to remember my symptoms and tell them about it.

When the Navy did call his parents, Jack's father, Leo, did not provide a stellar character reference. Leo said that Jack had been "boiling" for a long time and that he "has always been seclusive [sic], stubborn, head strong, resentful of authority and advice, being unreliable, unstable and undependable." He added that Jack "tends to brood a great deal."

Gabrielle's response suggests a lack of understanding of Jack's condition:

Tell me Honey what seems to be all the fuss out there. At first I thought you were sick, but now pop tells me you refuse to go through the training, or in other words refuse to serve your country. Oh Honey lamb,that's not like you, don't you know that it will be an awful mark against you? . . . . [I]t can't be that "bad."

A Scant Job History and "Bizarre Delusions"

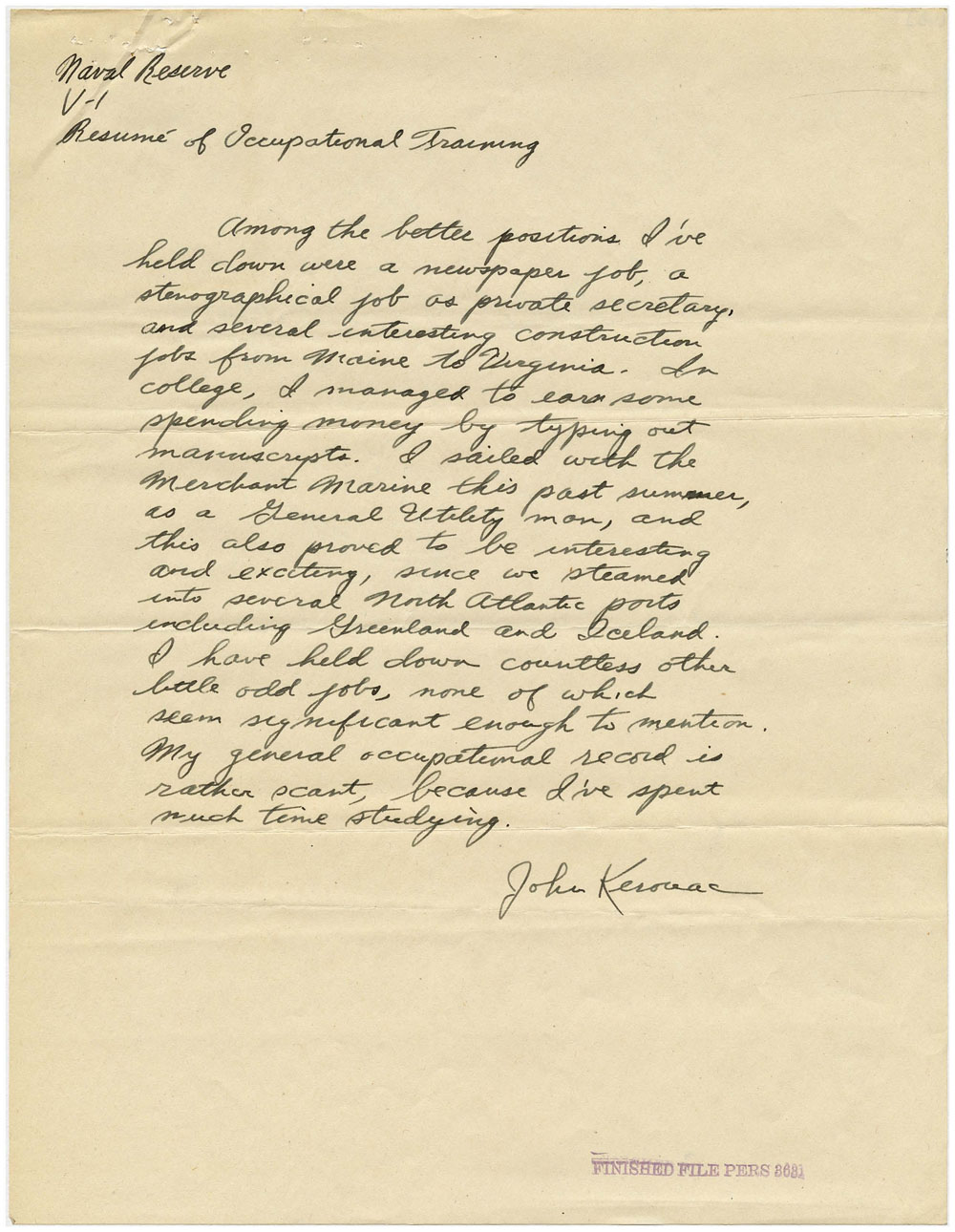

Navy doctors believed Kerouac's impulsivity contributed to his exceedingly erratic work history. Kerouac jumped from job to job and quit college twice. He had left the merchant marine after three months "because he was bucking everybody." He worked briefly as a sports reporter for the Lowell Sun but quit. Kerouac's "occupational" history concludes:

Very unreliable. Has been fired from every job he had except newspaper reporting. The latter was for a small paper at $15 per week, which he quit. He has been discharged from steamship job, garage job and waiter job. He is irresponsible and not caring.

The sole writing sample in his file, Kerouac's handwritten "Resumé of Occupational Training" lists his newspaper job and stint in the merchant marine but does not list what he termed "countless other little odd jobs, none of which seem significant enough to mention." He explained, "My general occupational record is rather scant because I've spent much time studying."

Kerouac recounts his move to the Naval Hospital in Bethesda in Vanity, stating that he "was put first in the real nut ward with guys howling like coyotes in the mid of night and big guys in white suits had to come out and wrap them in wet sheets to calm them down.

Just days after his official initial diagnosis, Kerouac told a friend why he was under evaluation: "One of the reasons for my being in a hospital, besides dementia praecox, is a complex condition of my mind, split up, as it were, in two parts, one normal, the other schizoid."

My schizoid side is . . . the bent and brooding figure sneering at a world of mediocrities, complacent ignorance, and bigotry exercised by ersatz Ben Franklins, the introverted, scholarly side; the alien side.

My normal counterpart, the one you're familiar with, is the half-back-whoremaster-alemate-scullion-jitterbug-jazz critic side, the side in me which recommends a broad, rugged America; which requires the nourishment of gutsy, redblooded associates; and which lofts whatever guileless laughter I've left in me rather than that schizoid's cackle I have of late.

Only through his writing could Kerouac unite these disparate parts:

And, all my youth, I stood holding two ends of rope, trying to bring both ends together in order to tie them. . . . I pulled—had a hell of a time trying to bring these two worlds together—never succeeded actually; but I did in my novel "The Sea Is My Brother," where I created two new symbols of these two worlds, and welded them irrevocably together.

Kerouac underwent analysis, challenging his doctors and playing on their preconceptions: Next came an investigation of the "bizarre" in me. First, "bizarre delusions." Was I the center of attention in a group? Of course!

"Extreme preoccupation" is another symptom of dementia praecox, a characteristic, I am proud to say, with which I am stricken. I cheerfully revealed this, and he cheerfully jotted it down.

Next, he tried to detect "unreal ideas" in my makeup. What was the strangest thing I'd ever seen? . . . I gave vent to an image compounded of all the mysticism I knew, from Poe & Ambrose Bierce to Coleridge and DeQuincey. A gleam in his eye!

In another letter in early April 1943, Kerouac joked about his condition:

(Surely, I am dementia praecox—just this afternoon, I was in such a melancholic stupor, the doctor showed concern.) And now! And Now! I feel fine and by God I'll tell the world.

Navy Psychiatrists Review Kerouac's Sexual History

The medical report's "sexual and marital" section notes that Kerouac had "sexual contact at age of 14 with a 32 year old woman which upset him somewhat." In addition, Kerouac "Enjoys rather promiscuous relationships with girl friends and is boastful of this. No apparent conflicts over sexual activity noted." Kerouac openly discussed such matters: "He has no shame, remorse or reluctance to describe his affairs." This openness will not surprise readers of Kerouac.

Again, Kerouac—at least in his correspondence—seemed amused by the questioning, and played upon the military's bias against homosexuality, as described in this undated letter:

The psychiatrist questioned me further, obviously in search of a blue-ribbon diagnosis. First he began to probe my emotional attachment, and found much food for thought there when I told him I wasn't in love with any girl, and didn't plan to get married at all. (This, of course, is pouring it on thick, but I wanted to see his reaction. He maintained a poker face & jotted down some notes—a superb performance!)

He wanted to know of my emotional experiences and I told him of my affairs with mistresses and various promiscuous wenches, adding to that the crowning glory of being more closely attached to my male friends, spiritually and emotionally, than to these women. This not only smacked of dementia praecox, it smacked of ambisexuality.

Kerouac addressed this issue more seriously in an early April 1943 letter: Sex, of course, is the universal symbol of life—I've discovered that all men, from aged veterans to sere academicians, turn back to sex in their last years as though suddenly conscious of its deep and noble meaning, of its inseparable marriage to the secret of life.

Navy Views Writers with Some Suspicion

Navy doctors viewed "patient's occupation as a writer" as a further sign of his mental imbalance. One doctor labeled Kerouac "somewhat grandiose" because:

Without any particular training or back ground, this patient, just prior to his enlistment, enthusiastically embarked upon the writing of novels. He sees nothing unusual in this activity.

A medical history excerpt from May 27, 1943, adds:

Patient describes his writing ambitions. He has written several novels, one when he was quite young, another just prior to joining the service, and one he is writing now. . . .

Patient states he believes he might have been nervous when in boot camp because he had been working too hard just prior to induction. He had been writing a novel, in the style of James Joyce, about his own home town, and averaging approximately 16 hours daily in an effort to get it down. This was an experiment and he doesn't intend to publish. At present he is writing a novel about his experiences in the Merchant Marine. Patient is very vague in describing all these activities. There seems to be an artistic factor in his thinking when discussing his theories of writing and philosophy.

Kerouac knew that his doctors viewed his writing with concern and yet played upon their preconceptions. In an undated letter to a friend, Kerouac recounted his responses to his psychiatrist's questions. Asked for more examples of his "bizarre behavior," Kerouac highlights his writing:

Spending my time writing. And oh yes, dedicating my actions to experience in order to write about them, sacrificing myself on the altar of Art.

"Bizarre behavior" . . . and the full diagnosis of dementia praecox. All this folly doesn't faze me, except for one item. Since I have "bizarre delusions," no one takes me seriously. Thus, when I asked for a typewriter in order to finish my novel, they only humoured me.

("The poor boy, now he's under the 'bizarre delusion' that he's a writer!")

Many aspects of Kerouac's personality viewed by the Navy as signs of mental illness were later praised as qualities that made him a gifted and expressive writer. In compiling Kerouac's medical history, Navy doctors wrote that he heard voices and "imagines in his mind whole symphonies; he can hear every note. He sees printed pages of words." Kerouac told his doctors that that he did not hear random voices but certainly did hear music:

I don't hear voices talking to me from no where [sic] but I have a photographic picture before my eyes; when I go to sleep and I hear music playing. I know I shouldn't have told the psychiatrist that but I wanted to be frank.

Kerouac's Hospitalization Brings Birth of an Icon

While it is impossible to know the full effect of his hospitalization and protracted analysis, Kerouac's letters suggest that time was turning point for Kerouac personally, professionally, and spiritually.

He spent the rest of his life running from structure, discipline, rules, regulations, and authority. The further he ran, the more he was embraced as a countercultural icon and embodiment of a new "Beat" way of life. One can only guess how much of his later escapades were in direct reaction to the strictness of his military experience.

Kerouac's hospitalization gave him time to ponder and solidify his self identity as a writer. From the hospital, Kerouac pledged a new beginning:

I must change my life, now . . . this does not mean I shall cease my debauching; you see . . . , debauchery is the release of man from whatever stringencies he's applied to himself. In a sense, each debauchery is a private though short-lived insurgence from the static conditions of his society.

In a letter to a friend from junior high school, written in early April 1943, Kerouac committed to starting his personal journey:

The pathos in this hospital has convinced me, as it did Hemingway in Italy, that "the defeated are the strongest." Everyone here is defeated, even this "broth of a Breton." I have been defeated by the world with considerable help from my greatest enemy, myself, and now I am ready to work. I realize the limitations of my knowledge, and the irregularity of my intellect. Knowledge and intellection serve a Tolstoi—but a Tolstoi must be older, must see more as well—and I am not going to be a Tolstoi. Surely I will be a Kerouac, whatever that suggests. Knowledge comes with time.

As far as creative powers go, I have them and I know it. All I need now is faith in myself . . . only from there can a faith truly dilate and expand to "mankind." I must change my life, now.

Hit the road, Jack, and don't you come back no more . . .

On June 2, 1943, the Navy completed its evaluation and changed Kerouac's diagnosis from dementia praecox to "Constitutional Psychopathic State, Schizoid Personality." The schizoid trends "have bordered upon but have not yet reached the level of psychosis, but which render him unfit for service."

The doctors suggested his discharge, and Kerouac signed a form stating that this condition was a preexisting one. On June 10, it was recommended that Kerouac be discharged "for reason of unsuitability rather than physical or mental disability."

On June 30, 1943, Kerouac's military duty was officially terminated "by reason of Unsuitability for the Naval Service." The Navy made it clear that he was not welcome to return; Kerouac "is not recommended for reenlistment." He was given "an outfit of civilian clothes," a travel allowance of $24.60 to return home to his not-so-supportive parents in Lowell, and a one-time "mustering out" payment of $200.

Kerouac left the hospital and hit the road.

His official military personnel file was closed 10 days later and remained closed for 62 years, until it was opened by the National Archives in 2005, unearthing a fascinating and previously unknown chapter in this legendary dreamer and writer's life.

Kerouac died in 1969 of internal hemorrhaging and was buried in his hometown of Lowell.

Miriam Kleiman, a public affairs specialist with NARA, first came to the Archives as a researcher in 1996 to investigate lost Jewish assets in Swiss banks during World War II. A graduate of the University of Michigan, she joined the agency in 2000 as an archives specialist. She has written previously in Prologue about the Public Vaults exhibit and about records from St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Note on Sources

Special thanks to Eric Voelz and Lenin Hurtado of the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, for their guidance.

Unless otherwise noted as a letter from or to Kerouac, all quotes are from Kerouac's official military personnel file, which includes an expansive and detailed 27-page medical history.

The letters cited in the article, written concurrent to Kerouac's time under psychiatric evaluation, are from Jack Kerouac: Selected Letters, 1940–1956, ed. Ann Charters (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1995).

Other sources include:

Paul Maher, Jr., Jack Kerouac's American Journey: The Real-life Odyssey of "On the Road" (Cambridge, MA: Thunder's Mouth Press, 2007).

Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee, Jack's Book: An Oral Biography of Jack Kerouac (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1978).

Jack Kerouac, Vanity of Duluoz (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1967).