Congressional Play-by-Play on Baseball

Summer 2011, Vol. 43, No. 2

By Adam Berenbak

In the summer of 1958, Dwight Eisenhower was in the White House, "Purple People Eater" was on the radio, and the New York Yankees were on their way to another American League pennant.

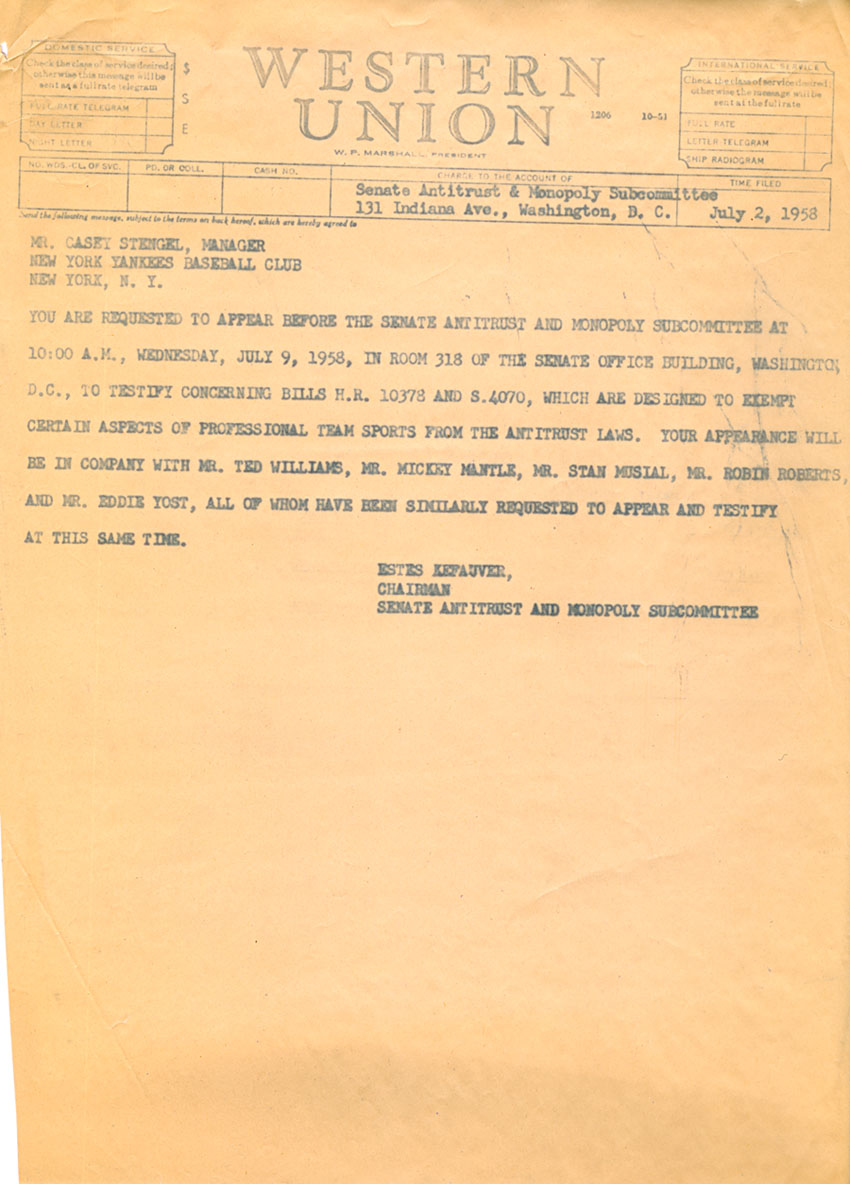

However, the baseball season was briefly interrupted when several major stars of the game, including Yankees manager Casey Stengel and superstar outfielder Mickey Mantle, were called before the Senate Judiciary Committee's subcommittee on antitrust and monopoly.

The hearings were held in order to ascertain the "applicability of antitrust laws to organized team sports." Baseball, exempt from antitrust laws since a ruling in 1922, was the first focus of the committee's efforts.

Though the Hall of Fame manager was known for shrewd and calculating decisions on the field, he was just as well known for his erratic and folksy style of speech off of it.

As manager of the most popular and successful team in baseball, as well as a professional in the sport for almost 50 years, Stengel was called early in the hearing for questioning. His disjointed way of speaking, often referred to as "Stengelese," was the delight of sportswriters and did not disappoint the assembled Senators.

When Senator Estes Kefauver, chairman of the subcommittee, questioned Stengel on his views regarding the motivations of professional baseball clubs with respect to antitrust legislation, Stengel's response quickly went off topic:

Of course we have had some bad weather, I would say that they are mad at us in Chicago, we fill the parks. They have come out to see good material. I will say they are mad at us in Kansas City, but we broke their attendance record. Now on the road we only get possibly 27 cents. I am not positive of these figures, as I am not an official. If you go back 15 years or if I owned stock in the club I would give them to you.

The baffled Kefauver replied "Mr. Stengel, I am not sure that I made my question clear" as the room filled with laughter.

Later, as Mantle took the stand, Kefauver continued his line of questioning. Mantle, always one to look for a laugh, could not help but reference his manager's ramblings. When asked by Kefauver if he had "any observations with reference to the applicability of the antitrust laws to baseball," Mantle replied, "My views are just about the same as Casey's." The entire room once again broke into laughter.

Records of Congressional Hearings Are Part of National Archives' Treasures

Records of hearings such as this are an example of the unexpected treasures contained in congressional records, and are just one facet of the wealth of information documented by Congress that can be found in the National Archives.

Congress has turned its attention to baseball, a sport at the heart of the American experience, for almost a century, a demonstration of the sport's place in American history. Baseball history can be documented and traced through its appearance in the records of Congress, especially in hearings before committees as well as on the floors of the House and the Senate. As one traces this path, the research value of congressional records is evident in the documentation of investigations, hearings, and legislation over the years.

The Center for Legislative Archives, the unit of the National Archives responsible for the care and use of the records of Congress, provides access to the American experience through a variety of materials and subjects covering almost 250 years.

Congressional records are composed not only of the official documents produced for legislation but also the daily work of House and Senate committees and subcommittees. Meeting minutes, reports, executive communications, and legislative files make up the bulk of the records. Much work goes into preparing and recording the frequent hearings and investigations, and the records appear in original, stenographic, and published form. These records provide a wealth of information on a variety of subjects.

While the official copy of what is said on the floors of the House and the Senate appears regularly in the Congressional Record, the hearings held to shape and build legislation in various committees and subcommittees have produced millions of pages detailing the rich history of the legislative process, and the history of the country.

Congressional Interest in Baseball Dates to Late 19th Century

The earliest mention of baseball in congressional records, for example occurred in various hearings in the House and Senate in the latter part of the 19th century. Most often these references speak to the recreational and pastoral aspects of a sport in its infancy, but they also illustrate the connection to interstate commerce and trade that attracted the notice of the legislative branch.

W.A.A. Carsey, chairman of the Anti-Monopoly League of the State of New York, spoke to the Senate Committee on Interstate Commerce in March of 1888 about "base-ball troupes, circus companies, theatrical companies and the like" complaining about the ill effects of congressionally manipulated railroad rates on their budgets. The diligent researcher will find further mention of baseball in Congress. Nineteenth-century congressional records document games among the troops waiting to ship out to Cuba, government employees involved in organizing teams, and baseball bats as cargo.

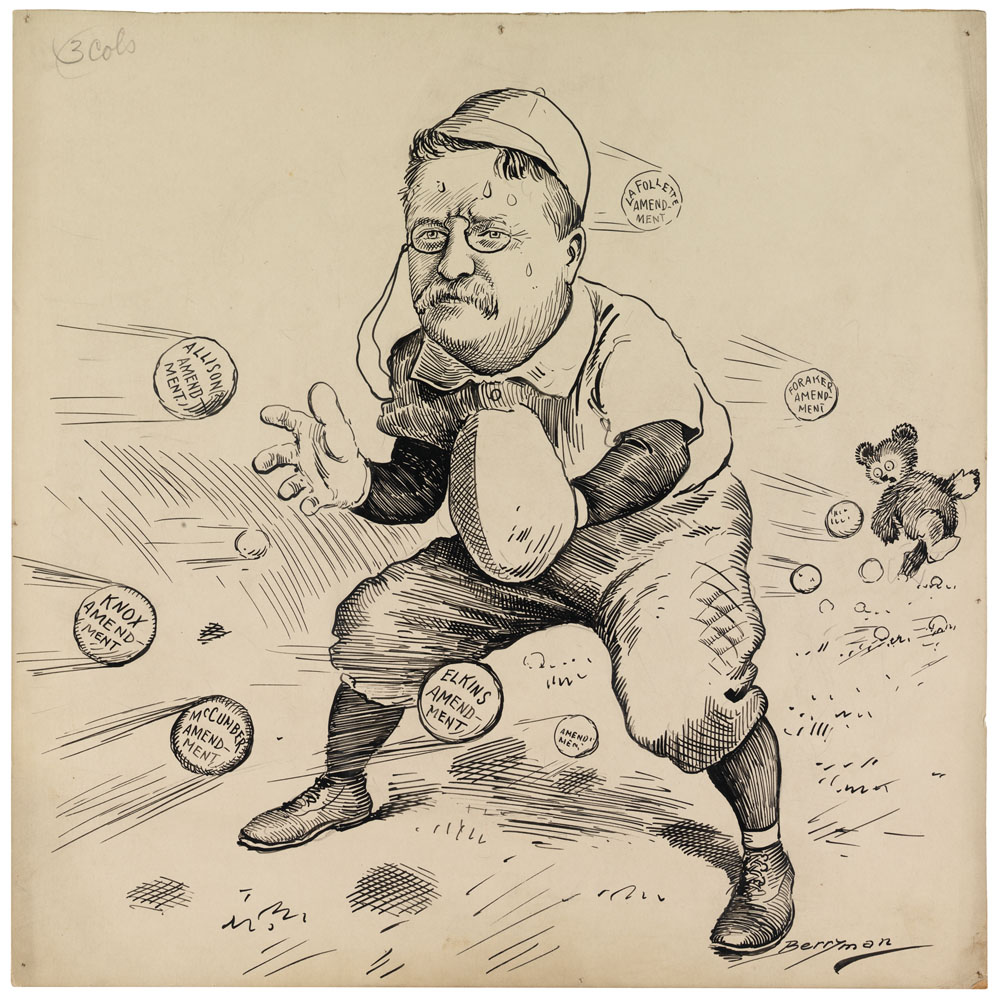

As the United States entered the 20th century, the government began to deal with the big businesses that had capitalized on post–Civil War prosperity and the industrial revolution. It was a time that baseball came into its own as a business.

Two leagues had emerged by 1901 as a consolidated Major League, and as other large industries had come under fire from antitrust trials and legislation, baseball was also scrutinized for its own monopolistic tendencies. The first hearings dedicated solely to baseball began to find their way onto the congressional agenda.

Congressional interest in baseball as interstate commerce continued to be the primary source of hearings before committees for the next 70 years. Labor issues, such as the legality of the reserve clause in professional contracts (which tied a player to one team in the days before free agency), as well as antitrust investigations were the most common topics.

Labor-Management Issues Begin to Take Center Stage

In July 1958, a hearing on the matter of antitrust law exemptions attended by more than a dozen of the greats of the game featured a recently retired Jackie Robinson. In pressing for fairness in the selection of those representing baseball, Robinson urged the appointment of a commissioner who "supposedly represent[s] the players and represent[s] the owners, represent[s] all of baseball" and should be selected by both players and owners.

As the profitability of the game increased, and franchises began to move to different cities, the issues of taxes regarding publicly financed stadiums came to the forefront. With the advent of television, and then cable television, both the House and the Senate became interested in compulsory licensing and interstate communications.

As revenue increased, and the players formed a strong union, labor disputes as well as copyright and intellectual property issues, especially associated with television (and now Internet) broadcasts, took center stage.

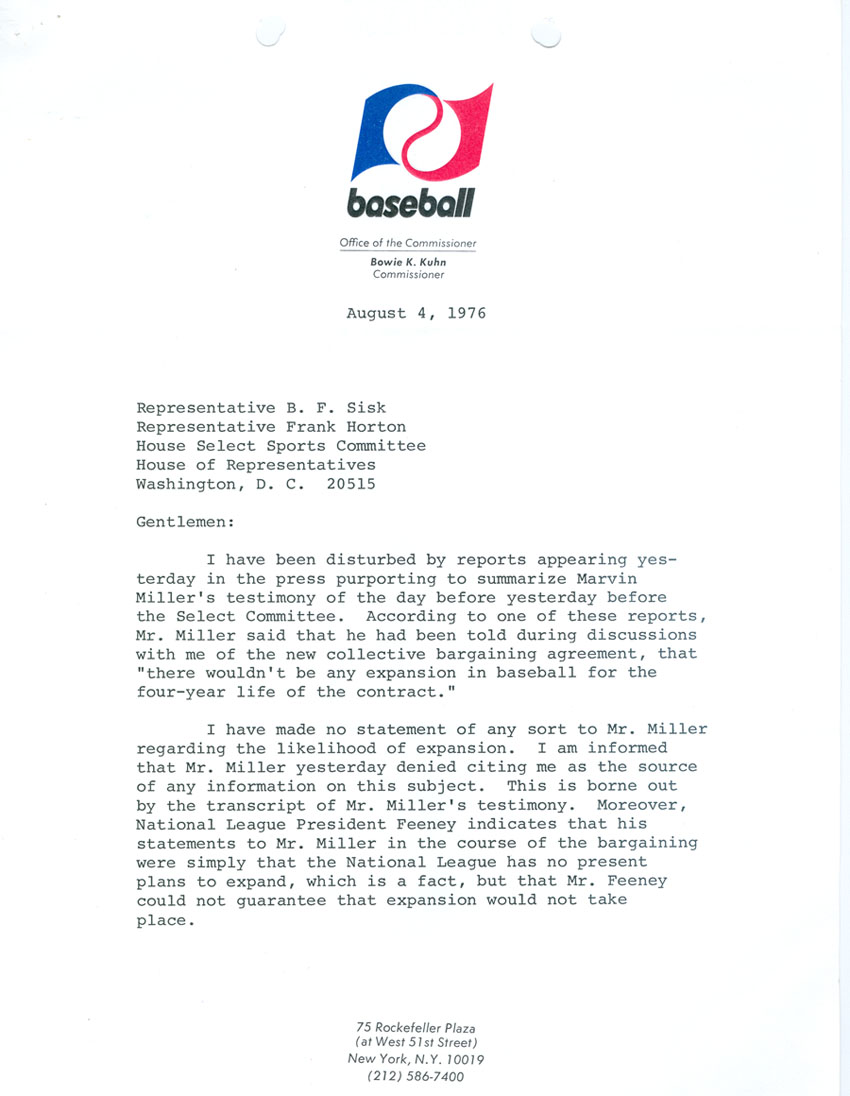

Because of the frequent focus on labor and compensation issues, two figures who appeared before Congress more frequently than other baseball figures were commissioner Bowie Kuhn and longtime players union chief Marvin Miller. The epic battle fought between these two figures, which spilled over into hearings before the House Committee on the Judiciary in the 1970s and 1980s, resulted in the advent of free agency and the skyrocketing salaries that continue to grow today.

Throughout the records of baseball hearings before Congress, one can find a hall of fame of names. Players such as Ty Cobb, Mickey Mantle, Stan Musial, and Joe Garagiola have testified before Congress on a variety of topics, from name franchising to sickle-cell anemia to civil rights and race discrimination in professional sports. And it was at the same hearing in which Robinson expressed his views on the office of the commissioner that the Senate antimonopoly and trust subcommittee allowed Stengel to ramble on for quite some time without ever coming close to the subject at hand.

Several former players, coaches, owners, and commissioners have even run for Congress. Only a few have been elected, most notably Hall of Famer and former Senator Jim Bunning of Kentucky and former North Carolina Representative Wilmer "Vinegar Bend" Mizell.

Ethics in the National Pastime Become Subject of Hearings

As baseball took hold not only as an American institution but also as a recognized piece of national identity, Congress began to focus more and more on issues regarding integrity and ethics in the game. Investigations into the impact of expansion in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the 1994 players strike, brought Congress closer to regulating ethical aspects of the game. During the latter part of the 20th century, Congress tackled more troubling subjects such as the continuing problem of race discrimination in professional sports, drug and tobacco use, violence, and the impact of these issues on fans.

The most famous of these hearings, titled "Restoring Faith in America's Pastime," occurred on March 17, 2005, when several of the game's biggest stars were called before the House Committee on Government Reform to analyze the growing problem of players' use of performance-enhancing drugs. The hearings involved such stars as Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Rafael Palmeiro, and Curt Schilling (appearing to voice his opposition to steroid use). Although none of the players faced accusations of perjury before Congress, popular opinion suggested that few of the stories they told were believable, and the hearings fed a growing sense of outrage among fans.

Though only a few players have ever been convicted of lying to Congress, the steroids investigations have proven to be the closest Congress has come to punishing those in baseball who didn't live up to the high standards required of an iconic sport.

In 2011, Roger Clemens was in court defending himself against charges that he lied to the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in February of 2008. The outcome may be one of the first major sanctions of the "steroid era."

Baseball history can be traced through its appearance in the hearings before Congress. Investigating first the vaudevillian and gypsy-like nature of professional baseball, Congress increased its scrutiny as the 20th century ushered in an age of major interstate commerce.

As baseball grew into an American institution, Congress investigated how the game influenced the fabric of society, attempting to add a level of government control from the elected voice of the people.

The records of these investigations and hearings, held in the Center for Legislative Archives, demonstrate how baseball is one of the many subjects of American history that can be profitably researched in the records of Congress.

Adam Berenbak is an archives technician in the National Archives Center for Legislative Archives. He earned a master of library science degree with a focus in archives from North Carolina Central University and was a 2008 Frank and Peggy Steele Intern at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum's A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown, New York. He has previously worked in both academic and public library special collections.

Notes on Sources

Transcripts of House and Senate hearings can be found in Records of the United States House of Representatives (Record Group 233) and Records of the United States Senate (Record Group 46) at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.