Jesse S. Haire: Unwilling Indian Fighter

Summer 2011, Vol. 43, No. 2

By Pam Milavec

© 2011 by Pam Milavec

When Jesse Spurgeon Haire came to his senses, he found himself standing in the deep waters of Cooper's Creek, his "belt around [his] neck" and his "carbine in both hands."

The soldier feared that his beating heart would either "burst" or betray his location. His fears came to fruition when three Cheyenne warriors "rode into the creek not over fifty yards from [him] and sat silently on their ponies listening for" any soldiers who had escaped their earlier ambush.

He wasn't sure whether his "gun went off" purposely, "or [whether] it went off accidentally," but the loud report left him no option but to "run through the bushes towards the cabins" of Cooper's Creek Station. Fortunately, passengers inside a stagecoach heard the gun go off and managed to save the hapless soldier.

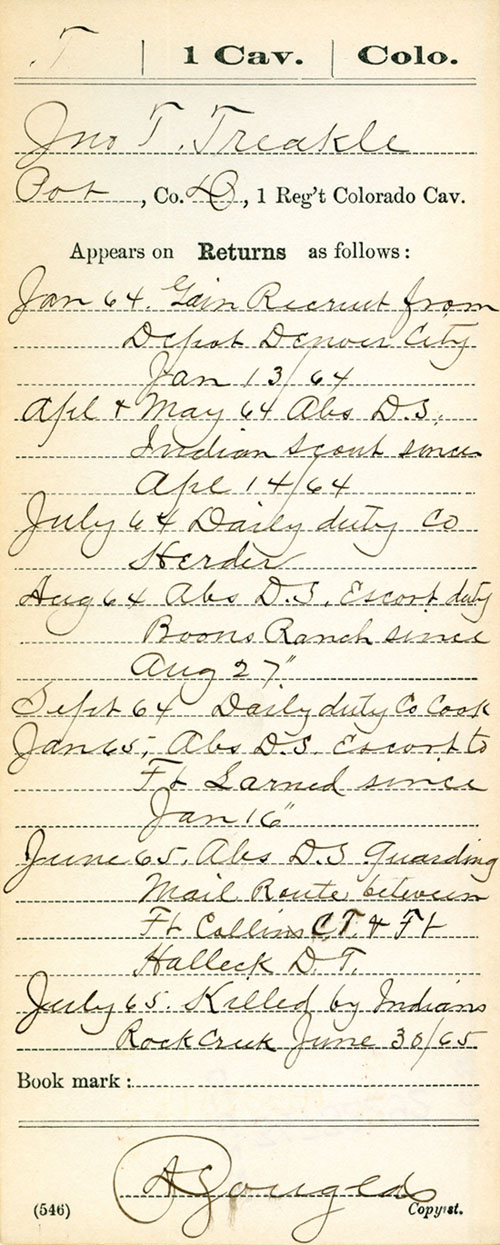

Safe inside the station, Haire reported the death of Sgt. John Thomas Treakle.

Treakle had set out with Haire and two other soldiers to investigate a reported sighting of two Indians in the vicinity. After agreeing to "stick together and not run away from each other," the group spotted a large body of Indians "coming around a hill," and the two other soldiers bolted away. One of the soldiers made it to the safety of the cabins, while the other had his horse shot out from under him, forcing him to "run to the brush along [the] creek."

After Treakle was unhorsed, Haire made an effort "to pull him up" onto his horse, but "another bullet settled [the sergeant] and he fell dead on the road." It was at this point that Haire's horse also succumbed to the onslaught, and the frightened soldier found himself in the water.

This incident was just one of several episodes that Jesse Haire experienced as a soldier providing escort along the Overland Trail in Dakota Territory, between modern day Laramie and Rawlins, Wyoming. Such military guards along the Overland's mail route became a necessity in the aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre, where Haire had been present as a member of the Colorado First Volunteers.

Haire Witnesses Atrocities at Sand Creek Massacre

In a series of journals and notes, from 1859 to 1897, Haire relates his encounters with such notables as Kit Carson, John Chivington, the James brothers, and a young Bill Cody and testifies to such events as the Colorado gold rush; Glorieta, the only major Civil War battle in the West; the Ute delegation to Washington DC.; and the Sand Creek Massacre. His writings also demonstrate just how small the world was in the 19th century as he encountered numerous friends and acquaintances from his home in Ohio.

When under fire, Haire referred to his Native American opponents as "mad wild devils out of hell let loose for a season." In less emotionally charged writings, however, Jesse relates his belief that "the whites are more to blame than the Indians in this war," although he does not blame the government.

Haire, fearful and bitter that people looked down on Colorado soldiers, complains that the First Colorado Volunteers had been "promised by [their] officers . . . to fight men who [were] trying to destroy the best government in this world." He also complains that they "would rather go under fighting secesh in the States than fighting Indians on the plains, for they [the Secesh] are the worse of the two."

On November 29, 1864, Capt. Silas S. Soule's Company D, to which Haire belonged, bore witness to the Sand Creek Massacre. Thanks in part to Soule's testimony at the Army's investigation of the incident and his impassioned pleas on behalf of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the atrocities that occurred at Sand Creek have long been common knowledge. Less well known are the thoughts and opinions of the men under Soule's command with regard to the massacre. Jesse Haire offers one such insight and gives a more complete picture than other testimonies given.

Haire's journey to Sand Creek and its aftermath was not a linear one. Haire worked his way from his hometown of Circleville, Ohio, to the Colorado gold mines when many who preceded him had already judged the gold to be "no more than a humbug."

Haire's relative acceptance of other cultures makes his an incongruent presence at Sand Creek. He made an effort to learn Spanish and socialized with the local population in New Mexico, encountered different indigenous nations, and addressed African American associates with the title "Mister."

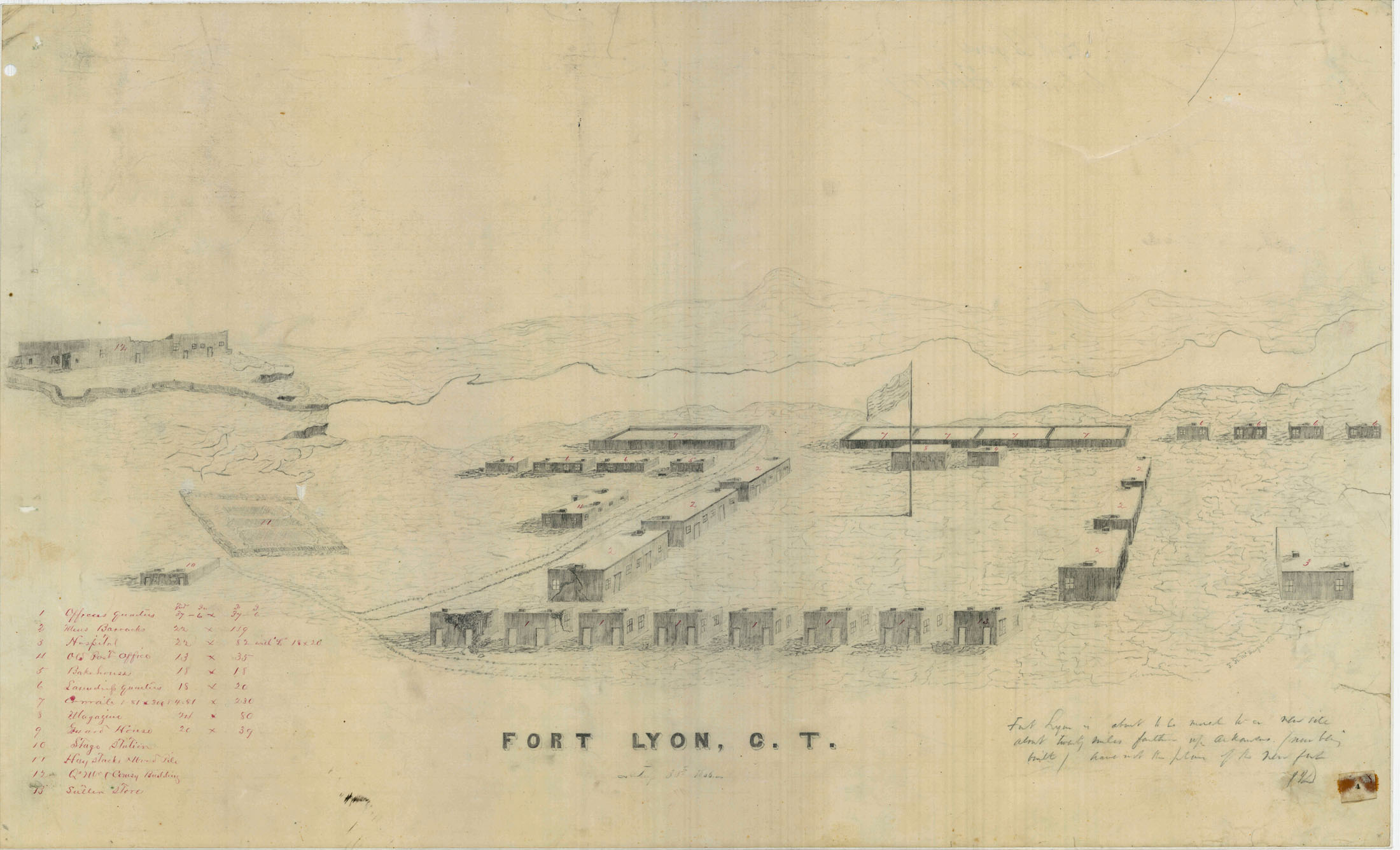

While placed on "provost or day time guard" to "prevent the soldiers from loafing about the Indians' camps" at Fort Lyon, Haire and the other guards became acquainted with Arapahoe chief Left Hand, who "talked to all of [them] in [their] own language . . . so good that [they] would suppose that some of [their] own boys was talking in the dark."

Haire states that Left Hand had been camped "inside the picket lines [at Fort Lyon] because he did not want to fight or encourage his nation . . . to fight against the U.S. government for. . . . [Left Hand's people] would get the worst of it." The arrangement worked well until Maj.r Scott Anthony replaced Maj. Edward Wynkoop as commander of the fort on November 5, 1864. Left Hand, according to Haire, complained that "Major Anthony doubted his sincerity about being a peaceable Indian and had insulted him." Despite Anthony's less than cordial attitude, Left Hand and the newly arrived Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle accepted the major's suggestion to wait along the Big Sandy, more infamously known as Sand Creek, for news of peace, or otherwise.

"The Chiefs Hollowing, the Squaws Crying . . ."

The Cheyenne and Arapaho camped at Sand Creek did not have to wait long for an answer. On the morning of November 28, 1864, Haire was surprised by "a large command of soldiers coming into the Post." He later recognized Col. John Chivington and Col. George Shoup with companies H, C, and E of the First Colorado Volunteers and about "six companies of the Third Regiment or the Hundred Day Militia of Colorado Territory."

Soon the forces at Fort Lyon had "orders to get ready and go with this expedition, destination not known to" them. Scouts reported "every half hour or so . . . as they travel[ed] on silently," through the night. Finally, "about an hour before daylight, it seem[ed] as though the scouts [were] disappointed in finding the enemy at the place they expected."

Scribbled above this account, Jesse later added, "Not one of our company knew where we was agoing or who we was to fight."

At dawn, Chivington's troops launched a surprise attack on the roughly 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho camped along Sand Creek. Initiating the attack, Lt. Luther Wilson led a battalion across the creek to the east side, where the main camp congregated, and "dismounted for a charge on foot." At this point,

Lieutenant Wilson's boys commenst [sic] shooting volley after volley and advancing as they shot into about five or six hundred chiefs, braves, squaws, papooses which was all huddled together in one crowd. The chiefs hollowing [sic], the squaws crying, papooses also and some would drop hanging onto those that still stood up.

Haire's description parallels the account given under oath by Major Anthony on March 14, 1865, to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of War: "the Indians, men, women, and children were in a group together."

Meanwhile, Haire in Company D, along with Company K, charged "on the gallop down the hill to the front . . . or south side" of the camp. Haire watched as "a young fellow by the name of George Pierce . . . gallop[ed] to save Mr. Smith, the interpreter," who had been in the camp at the time. Major Anthony also mentioned Pierce's heroic efforts to save John Simpson Smith, though he mentions Pierce only as "one of my men." Pierce was just about "to take hold of" Smith when "he was shot; at least" Anthony "thought so from his motions in the saddle."

Then, "after his horse was shot down [Pierce] attempted to get up and some Indian ran up to him, snatched his gun . . . and beat him over the head and killed him." Later, Haire noticed Anthony "looking at a dead horse and a dead man by the side of him."

As Haire approached, he recognized "the young man that charged in." Haire added, "him and his horse had both been shot dead for his rashness." George Pierce holds the distinction of being the first soldier killed at Sand Creek.

Sometimes depicted as the sole holdout at the massacre, Captain Soule, according to Jesse, conferred with his men at some point before crossing Sand Creek:

"Boys, do you know who you are fighting today?"

"No," someone said.

"Well," then said [Soule], "We are fighting Left Hand and his band." Then a man, a Mr. Lynch said, "Well, we won't fire a shot today." The others hollered the same thing.

Then, the Capt said, "I don't ask you to shoot, but follow me and we will mix in this fuss and go through it. So, come on boys," and away we go on the gallop down through the cross fires of both sides to [the] north end.

In his unfinished autobiography, Edward Wynkoop provides concrete support for Haire's account. Wynkoop writes, "Soule . . . along with his men refused to fight." Soule himself never claimed to stand alone in his opposition to the massacre. In a letter written by Soule to Wynkoop after Sand Creek, Soule states only that his company "was the only one that kept their formation."

Seeking Refuge in the Sand Holes

Aware of their exposed and vulnerable position, many of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe sought refuge in hastily dug trenches in the sand. As Company D "rode down into the creek" to cross, Jesse saw members of Colonel Shoup's command "shooting shells into the sand holes to scare the Indians out." Jesse recorded his amazement at the number killed and wounded there.

The relatively high number of soldier casualties—nine killed, 38 wounded—is often used by Sand Creek defenders both to discredit the peaceful intent of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe and the number of able-bodied warriors present at the time of the attack. Haire, however, pontificated that

The reason the Third Regiment boys suffered so much was they rushed up to the banks of the creek when the Indians was trying to get into their holes, which give the Indians a fair chance to pick them off. . . . In this way a good many of the thoughtless boys got hurt and killed.

In one of the sand holes, Jack Smith, the half-Cheyenne son of interpreter John Smith, concealed himself with "a lot of other Indians." Haire heard him agreeing in English "to come out [if] they would not shoot him." Though some of the soldiers accepted Jack's offer, they "had their revolvers ready to shoot." Wisely, Jack "would not take their word for it and he did not come out."

Meanwhile, Haire saw Major Anthony crossing the creek to their position, coming too close to the sand bank or "holes." Haire and others "holler[ed] at him [not to] come too close for he was a good close mark for the concealed Indians."

After Anthony reached them by maneuvering to the left, he convinced Jack Smith "to come out." Jack Smith's rescue proved futile, however; he was murdered the following afternoon while sitting with a scout inside a lodge, according to Anthony, with Colonel Chivington's approval.

The Day's Brutality Comes to an End

The normally descriptive Haire mentions few gruesome details of Sand Creek. He does mention "a company or two of the Third [Regiment]" who shoot down some escaping Indians "whilst they was hugging to each other in despair, and he adds that he saw "two shot through at once as they was in this fix." In another instance, he witnessed "several of those ranchmen or Hundred Daysman" in pursuit of two fleeing young women. Haire watched long enough to observe, "the girls was so scared that they put their arms around each others' necks" before the "men commenst to fire at them." Whether from compassion or because he had moved out of view, Haire said that he "could not look in that direction again" and could not "say what was done for [he] could not help them by [him]self."

At some point, Haire "noticed . . . that the teepees or wigwams was nearly all on fire." Though he did not know who started the fire, he surmised "that they were stragglers from all companies that was after plunder and all the fancy things the Indians had." Later, he saw that "most all the boys had all kind of Indian trophies and some had ponies loaded down with them."

Not satiated by the day's brutality, some "of the boys" shot at "the Indian dogs" that howled eerily from "every direction." Other "heartless boys" busied themselves by throwing "ten or fifteen young pups . . . in the fire to burn alive."

That night, the soldiers of Company D, with no blankets "lay down under [their] saddle blankets and overcoats" in the wind and snow. The morning found their situation little improved. With "nothing to eat," they "st[ood] and shiver[ed]" alongside their "shaking" "horses."

If the soldiers who had joined Chivington's command with "three days' cooked rations and twenty uncooked" spent the night in such wretched conditions, the Cheyenne and Arapahoe survivors must have experienced circumstances beyond comprehension.

A Methodist Preacher Draws Haire's Attention

Haire wrote his original commentary of the massacre diary style but added comments and revisions wherever he managed to find space, in typical Jesse style, along the top and bottom of pages, between lines, or up and down the sides.

As part of the revision process, Haire also went through and crossed out lines in an attempt to record only those things he witnessed. In one such instance, he refers to a white flag, though it is unclear whether he means the oft-debated white flag of Black Kettle or the white flag waved by John Smith. Whatever his original intent, Haire explains beside a series of seven crossed out lines, "these things about a white flag, I did not see, but only heard others say . . . so I scratch."

Interestingly, Haire offers no insight on any impression Silas Soule may have made on him or the men of Company D. Despite Soule's affable historical reputation, no apparent close bonds formed between the captain and Pvt. Jesse Haire. He mentions Soule only in reference to events.

This lack of adulation contrasts sharply with Jesse's early impressions of John M. Chivington. Small-statured Haire seemed taken by the larger than life Chivington from the first time he saw him. While working in Nebraska City on his way west, Haire sometimes "went to the Methodist Church to hear their elder of the church preach," a "Mr. Chivington."

Haire describes Chivington as "a very large man about 6 feet 4 and large in proportion" who "says just what he thinks regardless of consequences." Haire adds, "he has a brother who is as large as he" who served as "the minister of this church."

Haire also relates the already popular story of how the "fighting preacher" earned his moniker by confronting a Missouri congregation who "intended to whip" him the "next time he came there." After taking the podium and "roll[ing] up his sleeves," Chivington asked "that part of his audience [who] wanted to fight . . . whether they would have it before preaching or after preaching." Missing from Haire's account are the "two pistols, one on each side of the Bible," made legendary by Reginald S. Craig in his biography on Chivington.

Haire is no less awestruck when he crosses paths with Chivington in Colorado Territory during his mining days. Once again providing a physical description of the generously proportioned man, Haire claims that "the miners dropped their picks and shovels and the gamblers dropped their cards and dice and we all ran up together" to hear Chivington preach "Christ and him crucified" "up on the mountain side in the pine timber."

The contrast between Haire's treatment of Soule and Chivington prior to Sand Creek provides a poignant backdrop to an examination of his feelings after the massacre.

An Assassination Attempt on Captain Soule Succeeds

Not even a month after Sand Creek, a motion passed the House of Representatives for an investigation by the Committee on the Conduct of War. Two additional investigations into Chivington's conduct would follow this one, a military commission and an investigation by the Joint Special Committee, the purpose of which was to investigate the treatment and condition of Indian tribes.

Soule appeared before the military commission on February 15, 1865. He was questioned for two days, followed by a four-day cross-examination by Chivington and a daylong reexamination by the commission.

Soule provided his testimony despite various threats on his life and at least two actual assassination attempts. On February 24, 1865, the Daily Mining Journal reported, "assassins have twice attempted the life of Capt. Soule within six weeks; Soule is a witness who expects to testify before the Court of Inquiry and his testimony is evidently feared; hence he is shot at nights in the suburbs of Denver."

Earlier, on February 9, there had been a meeting at the Denver Theater to obtain volunteers to fight Indians. Many members of the military were there. Colonel Chivington was called upon the stage and "requested his name be put down for five hundred dollars." In the speech that followed, Chivington declared that he advocated not only the killing of Indians, but also "all the Indians' confederates."

Whether encouraged by Chivington's speech, or acting of their own volition, two men, Charles W. Squiers and William Morrow, shot Soule dead on April 23, 1865, at the corner of 15th and Arapahoe in Denver, where Soule served as provost marshal.

Jesse's account of Soule's murder includes a third man:

[M]any of the boys of the Second Regiment recruits was on a spree down in the city and last night their orderly, Srgt Mr. Squires and another young fellow was in the company shooting off his or their pistols in the company with [Haire leaves a space for a name] who lives down the Platte River.

Haire relates, "their shooting attracted the attention of Capt. Soule the Provost Marshall and the Captain of Company D, our company" who "ran out around one of two corners of the street and met these fellows." He reports that Captain Soule had been "shot dead, the shot going in below his right eye." Though he admits that "we do not know the circumstances, he refers to the fugitives as "assassins."

More telling than Haire's matter-of-fact recounting of his captain's murder are the seemingly unconnected notes written conspicuously near the announcement of Soule's death. In this note, Haire makes no mention of Soule and makes no direct accusation against Chivington.

Still, Haire's rant makes his animus clear. He records his "astonish[ment] at [Chivington's] actions since" he preached to the miners and gamblers on the mountainside. Jesse condemns Chivington for betraying "Left Hand, that good, peaceable chief, who tried to keep all the braves and the families of his people peaceable . . . .when the balance of his nation was cursing him and trying to get him to come out on the war path and lead them into battle."

Haire was "shocked at" the former preacher's "language, for he could roll out blasphemy and big oaths as easy as any old sport or boat captain." When Haire sees Chivington "in an uptown fashionable saloon," he is "surprised to see him holding that sparkling beverage that [had often] beguiled [Jesse] into trouble." "No wonder," he reproaches, "kind providence let him fall into disgrace and die in disgrace." The reference to Chivington's demise could indicate that Jesse wrote his condemnation after learning of Chivington's October 4, 1894, death.

Sand Creek Is Considered Massacre, Not a Battle

Few days in Colorado history elicit as strong opinion as the Sand Creek Massacre. The findings of the three investigations were unanimous; no "great battle" had taken place, Sand Creek was a massacre.

Chivington, who had resigned from the military, and was therefore immune, escaped punishment but did not escape condemnation, either from Haire or from the United States government. The Joint Committee on the Conduct of War declared that they could "hardly find fitting terms to describe his conduct. Wearing the uniform of the United States, which should be the emblem of justice and humanity; holding the important position of commander of a military district, and therefore having the honor of the government to that extent in his keeping, he deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre."

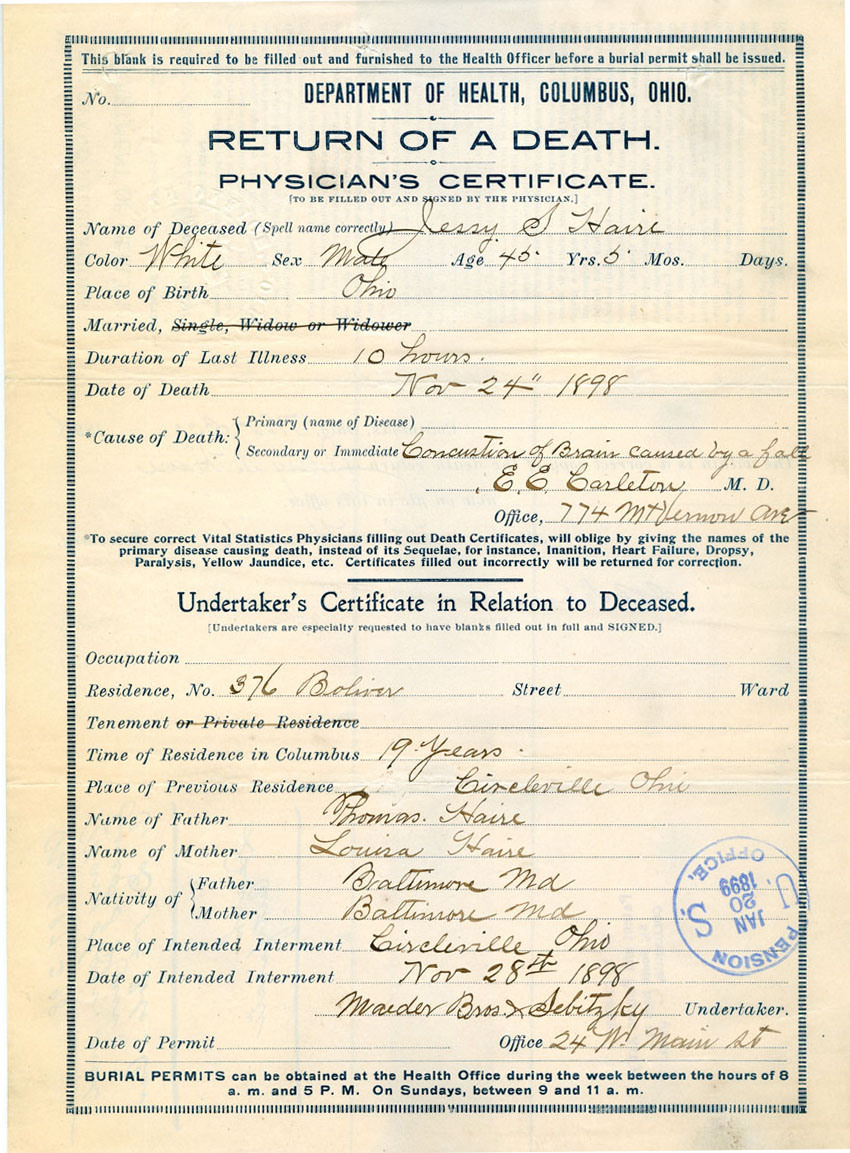

Sometime after his discharge on October 26, 1865, and before his marriage to Mary Elsey on October 5, 1871, Jesse Haire made his way back home to Ohio. He outlived the "fighting preacher" by only four years. On November 24, 1898, he tripped on the basement steps at his home in Columbus, Ohio, and hit his head, never regaining consciousness. He died 10 hours after the accident, an innocuous end for the little man whom "kind providence" had rescued so many times before.

The lessons of Sand Creek continue to educate; the voices refuse to be silent. One such voice, that of Jesse Spurgeon Haire, does away with the romantic image of the dashing young Captain Soule who stood alone, forbidding his men to fire. In return, Jesse offers a more complex view of the Colorado soldier who served during the Civil War. One wonders what other Sand Creek voices the future will resurrect?

Pam Milavec received undergraduate degrees in both history and English. She is currently pursuing her M.A. in history at the University of Colorado at Denver and is employed by Denver Public Schools. She has researched extensively and published on Native American–white relations. Current projects include the transcription of the Jesse Haire Journals, 1859–1897, and a biography of Capt. Silas S. Soule.

Note on Sources

The Jesse Haire Journals: 1859–1897, reside at the Ohio Historical Society in Columbus, Ohio.

Haire's pension file (widow's pension WC485043) is in the Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15. John Treakle's service record is in the Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780s–1917, RG 94. Both records are found in the National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Where Haire identified the location of the incident in the opening paragraphs as Cooper's Creek, both Sergeant Treakle's service record and Capt. Luther Wilson's report of the incident identify the location as Rock Creek. Another disagreement with events recorded in the journal is the account of Jack Smith's murder at Sand Creek. Interpreter John Smith testified to the Committee of the Conduct of War, "I had a half-breed son there, who gave himself up. He started at the time the Indians fled; being a half-breed he had but little hope of being spared, and seeing them fire at me, he ran away with the Indians for the distance of about a mile. Fearing the fight up there he walked back to my camp and went into the lodge." It could be that John Smith was unaware of Jack's struggle in the sand, or that Haire mistakenly identified another man for Jack.

On Chief Left Hand, see Margaret Coel, Chief Left Hand: Southern Arapaho (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1981). Stan Hoig, The Sand Creek Massacre (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1961) and The Western Odyssey of John Simpson Smith (Glendale, CA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1974) are valuable sources.

Quotations from Edward Wynkoop are found in The Tall Chief: The Autobiography of Edward W. Wynkoop (Denver: Colorado University Press, 1994). The story of Chivington's prewar reputation is from Reginald S. Craig, The Fighting Parson: Biography of Col. John M. Chivington (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1959). Craig's credited source for his version of the "fighting parson" story comes from John Speer's Report to Fred Martin of Interview with Mrs. John M. Chivington, March 11, 1902. Chivington's speech in Denver is reported in the Rocky Mountain News, February 9, 1865.

War of the Rebellion,: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. 41, part I, p. 948, contains Chivington's report to General Curtis after the massacre.