The Rejection of Elizabeth Mason

The Case of a "Free Colored" Revolutionary Widow

Summer 2011, Vol. 43, No. 2 | Genealogy Notes

By Damani Davis

In May of 1854, 90-year-old Elizabeth Mason, a "free woman of color" from Campbell County, Virginia, appeared before a local Justice of the Peace to apply for a military widow's pension.1 She declared that her deceased husband, Thomas Mason—also a "free man of color"—was a Revolutionary War veteran who had first volunteered in 1777, joining a militia company based in his native Caswell County, North Carolina.

Thomas Mason was one of approximately 5,000 African Americans who served in Patriot military forces during the Revolutionary War.2 Initially, most Patriot leaders—including Gen. George Washington—were disinclined to accept African American servicemen into the armed forces. Officials in some of the former colonies were vehemently opposed, especially in such states as South Carolina and Georgia, where leaders repudiated the idea of black participation for the entirety of the war.

But as deficits in manpower and the need for new recruits continued to increase, officials in most states eventually welcomed the service of African American troops at various levels.3 Once black recruits were allowed to enlist in Patriot forces, they were quickly absorbed into units that had been suffering chronic shortages and recruitment deficits. No distinctions were made in the pay and bounty offered to these black recruits.4

Ironically, for nearly two centuries, the Revolutionary War would be the last American conflict to employ integrated troops. After the nation gained independence, all African Americans serving in the United States military would be relegated to segregated units. Not until the Korean War, after President Harry S. Truman ordered the desegregation of the United States armed forces, would there be integrated troops again. The military's last all-black unit was officially disbanded in 1954.5

African American Service during the American Revolution

The level of African American involvement in the Revolution depended upon the region, state, and status of the potential black recruit. Out of the states that did allow black participation, most restricted African American enlistment to those who were legally identified as "free blacks."

Since the free blacks represented only a limited segment of the overall black population, a large portion of African Americans were automatically excluded because of their status as slaves. Those states most highly dependent on slave labor and plantation economies tended to be most resistant to black participation, whereas states less dependent on slave labor tended to be more open. This trend is reflected in the numbers of black servicemen that were documented in armed forces of various states during the revolution.

The New England states had the largest total of African American military participation despite the fact that the overall black population was smallest in that region.6 Scholars suggest that the smaller black population in the New England states meant that whites had less apprehension or reluctance to arm African Americans.

At the opposite extreme were the heavily slave-based plantation societies of South Carolina and Georgia, where members of the state legislatures rebuffed the notion of arming black troops. Since areas of those two states contained substantial black majorities, the dread of potential slave revolt outweighed any concerns of a British invasion.7

Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, however, did not adopt the extreme position held by South Carolina and Georgia. Outside of New England, Virginia recruited and enlisted more African American servicemen than any other state. Like most of the northern states, Virginia restricted its black recruits to those who were legally recognized as "free blacks or mulattoes." Like citizens of other plantation states, Virginians were averse to the notion of recruiting and arming the enslaved. Not only was there the possibility of revolt, but slaves were also regarded as costly property and an investment too valuable to risk losing through injury or death.

Despite these reservations, a significant minority of Virginia's black recruits consisted of enslaved blacks who were allowed to serve in the place of their owners. Any slaveholder who sought to evade the draft and military service could have one of his slaves serve in his stead, often with the agreement that the slave would be rewarded with freedom afterwards.

North Carolina's policies were similar to Virginia's, while Maryland was the only southern state to completely authorize unrestricted African American enlistments—regardless of whether the recruit was enslaved or free. In each of these states, the black recruits—whether free or officially enslaved—served alongside and in the same units as their white compatriots. Such was the case of Thomas Mason, who enlisted in North Carolina; fought in Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and North Carolina during the war; and settled in Virginia.8

Thomas and Elizabeth Mason From the Commonwealth of Virginia

Mason moved first to Louisa County, Virginia, where he met and married Elizabeth Ailstock in 1791.9 The marriage ceremony was performed at a local Episcopal church and presided over by a Reverend Douglas. The Masons later moved to Campbell County, where they resided for over 50 years.

Six children were born to the Masons, but only one of the children, Thomas Mason, Jr., was alive when Elizabeth filed the pension claim. The oldest child, the Masons' 60-year-old daughter, had died recently, just prior to the claim. Fifty-seven-year-old Thomas, Jr., who was described as a successful butcher in the Lynchburg market, served as one of the witnesses and provided a signed statement verifying his mother's testimony.

Elizabeth provided specific details on her husband's service, stating that he had served three separate tours. In the first, a six-month tour, he served at the Battle of White Marsh near Valley Forge in Pennsylvania and was assigned to a "horse company."

He volunteered a second time, for three months, "under Captain Wilson and Colonel Moore"10 and served at Gen. Horatio Gate's defeat at Camden, South Carolina. Thomas's third and final service was another three-month tour in 1787, again under Captain Wilson and Colonel Moore, during which he served at the battle of Guilford Court House in North Carolina. Elizabeth said that after each of his three tours, Thomas was honorably discharged.11

Elizabeth explained that she knew these details because she had "frequently heard [him] narrate scenes and circumstances which occurred during his service" and also had "frequently seen his 'Discharges.'"

In 1832 Thomas had proceeded to file his own pension claim according to the terms of the pension act of that year. To facilitate the process, he obtained the services of a prominent Virginia lawyer, Maj. James B. Risque, to whom he submitted the copies of his discharge papers. Mason and Risque then traveled together to Thomas's native North Carolina, where they gathered other pertinent documents and evidence relating to his service.

Unfortunately, Mason died on October 17, 1832, while he and Major Risque were preparing his claim. Upon his death, his lawyer abandoned the petition, and the matter ceased.

Elizabeth Mason Files a Pension Claim as a Widow

Twenty-two years later, Elizabeth decided to pursue the claim as a widow because she was then "very old and infirm and scarcely able to walk" and needed the benefits.12 By that time, Major Risque had also died. Both of the men's families searched diligently through Risque's papers but were unable to locate any of the records relating to Mason. The absence of these documents hindered Elizabeth's petition and required her to provide additional evidence in the form of witnesses and affidavits to substantiate her claim. Undeterred, she enlisted the services of Virginia attorney Charles W. Statham.

The loss of Mason's military records was certainly a major setback for Elizabeth, but Statham believed he could collect sufficient evidence to substantiate the claim. Statham tracked down Thomas's payment records for his militia service in North Carolina. He received from the state comptroller of North Carolina a certified letter that stated, "I, William J. Clarke, Comptroller of Public Accounts . . . hereby certify that it appears on record in my office, among the payments made by said State to sundry persons for Military services in the Revolutionary War as follows to wit: Thomas Mason," demonstrating Mason's service as a volunteer.13

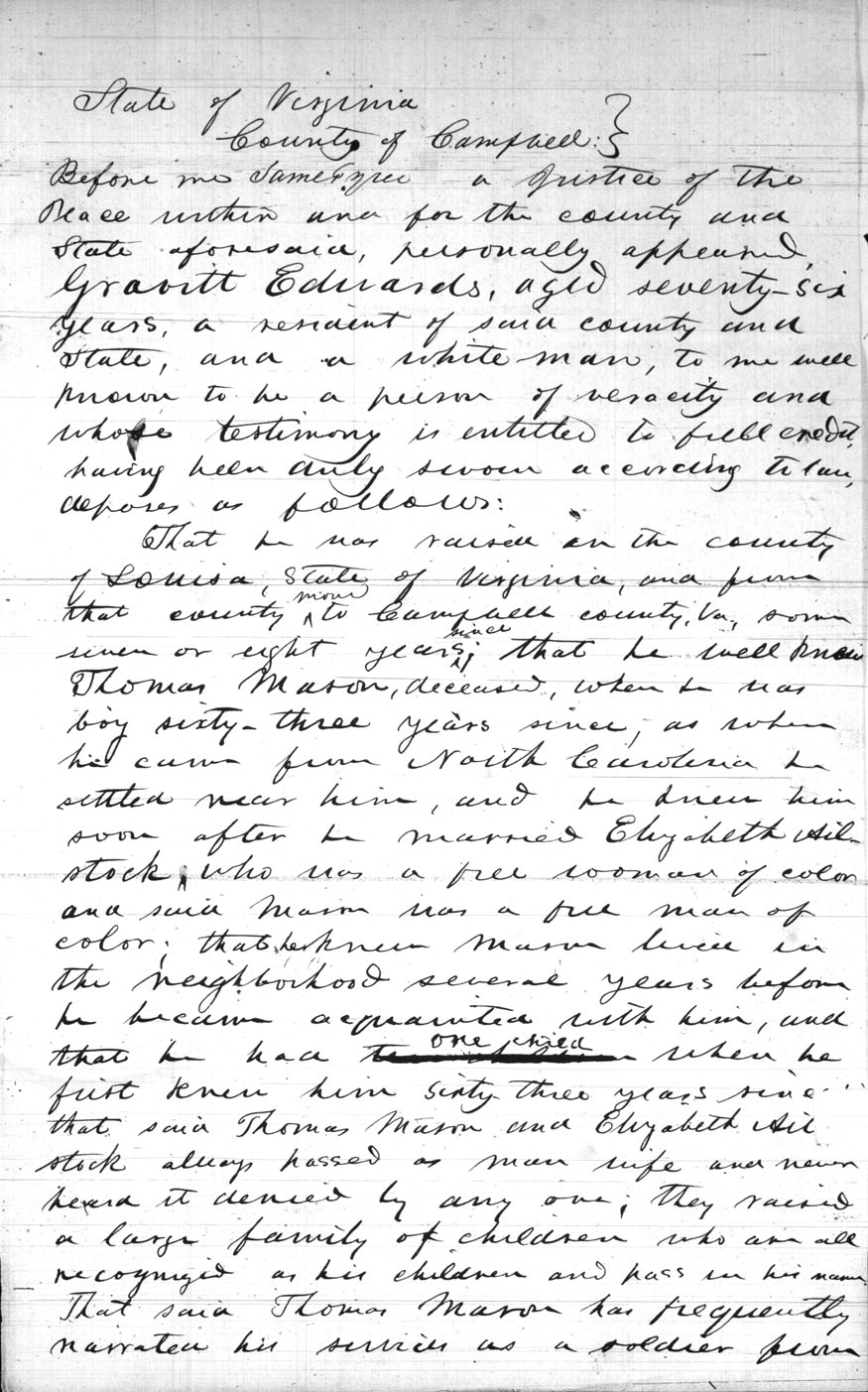

In addition to the pay record, Statham collected signed affidavits and testimony from several witnesses who were well acquainted with Mason. Benjamin Farmer, William Lee Fair, and husband and wife George and Mary Gruber were long-time white neighbors in Campbell County; Gravitt Edwards was a white neighbor who had known Mason back in Louisa County; and Samuel George, a free black neighbor, who along with Thomas Mason, Jr., was the only other African American witnesses.

Gravitt Edwards had known the couple the longest, having met Mason 63 years before "as a young man," when the former soldier first moved from North Carolina to Louisa County and married Elizabeth Ailstock. Edwards confirmed that he had frequently seen Mason's discharge papers "and that none of his neighbors [had] ever doubted or questioned his services as a soldier; that great respect was paid him on account of his having served his country, and more privileges were then allowed him with his neighbors than other free persons of color."

Mary K. Gruber was raised about half a mile from the Mason family in Campbell County and knew them all. She testified that she and her husband, George, were actually visiting her mother, Mrs. Ellena Flowers, the day that Mason died. She said that she remembered the day clearly because word of his death had spread quickly among the neighbors of the general area, which indicates the esteem in which Mason must have been held.14

Benjamin Farmer and William Lee Fair of Campbell County concurred with Gruber's statements, testifying that it was common knowledge in the area that Mason had served in the "War of the Revolution" and that they had often heard him talk about his service and had never heard anyone deny it. Of Thomas and Elizabeth's marriage, Farmer stated that they "lived together as man and wife from the time of my first knowledge of them, and were always currently believed and reported to be such; that they raised a family of children—six in number . . . ; that the belief and report of them being lawfully married was universally believed, and [I] never heard the report or belief contradicted." Farmer had known the family for approximately 50 years, and Fair had known the Masons for about 41 years.15

Samuel George, the free man of color, had known the Masons for about 50 years and basically recapped the assertions of the other witnesses. He had frequently seen Mason's original discharge papers verifying his service and recollected that he had "always spoke of serving three tours." He also remembered and corroborated the account of Mason and Major Risque preparing a petition for the pension and traveling to Caswell County, North Carolina, to obtain additional evidence.

George concurred that Risque had collected all of the documents, but Mason died soon thereafter. He further corroborated, "the claim then remained unattended to since when said Risque also died; and though diligent search has been made among his papers by his daughter—Mrs. Ward—they cannot be found."16

Charles W. Statham Fights The Denial of a Pension

Despite Attorney Statham's efforts, the Pension Office ultimately denied Elizabeth's pension claim. The commissioner of pensions, Loren P. Waldo, signed the initial rejection letter. Waldo argued that the declaration "should have been made before a court of record and not before a Justice of the Peace."

This policy required that each claimant appear before a "court of record" in his or her state of residence and describe under oath the service for which the pension was claimed. He further noted that "the certificate" provided by "the Comptroller of North Carolina" did not show "that the soldier referred to in [the] certificate was 'a man of color.'" Thirdly, "the marriage [had] not been properly established." Finally, Waldo rejected the application because the declaration claimed service 'in the Line of the Army,' while the payments show 'militia service only.'"17

A determined Statham immediately responded to the denial. In his reply letter, he addressed each rejection point by point. Against the first objection concerning the "court of record," he explained the legitimacy of the "Justice of Peace" system in his state of Virginia. He wrote:

You are doubtly [sic] aware that Justices compose our Court of Record having a presiding Justice, which court has as high jurisdiction and its members separately as the Judges in many of the States. In fact, I believe most of them have not as high power as our Justices. We have no county Judge at all in Virginia, though we have what is called a District or Circuit Judge, embracing a large number of counties in his Circuit.

He explained that due to her fragility, Elizabeth Mason was unable to appear in open court before a district judge. Regarding Justice John P. Knight, the justice before whom Elizabeth had made her declaration, Statham stated that Knight had:

left the bench where he was presiding as one [which] constituted a Court of Record, and went with me from the Courthouse to visit this old woman, and take her Declaration. He certifies to her inability to attend in open Court, on account of old age and infirmity, which is literally true, and it would be impossible for me to get her to the Courthouse. She is 90 years old and very infirm, and is physically unable to move about. If it is regarded as essential by the Department, I will get the Presiding Justice to visit her, and certify as to her inability to attend in open Court, for I have to get them to go to see her.18

Thus, he contended that "the rules of your Office in such cases, has been complied with, inasmuch as it is specifically set forth that, the reason why Mrs. Mason did not appear in open Court, was by reason of bodily infirmity induced by old age."

Statham Gets Some Assistance from North Carolina's Comptroller

Regarding the second objection claiming that the certificate from the comptroller of North Carolina had not identified Thomas Mason as a "free man of color," Statham countered that "no such distinction was made on the muster rolls or in any certificate given to free negroes from North Carolina or Virginia. Both black and white, if free persons, stood on the same footing as Militiamen, no distinction being made as to color, which I hope will remove that objection. But if the Department thinks proof necessary as to that fact, I will procure the letter or certificate of the Comptroller, that these certificates never specify color." Indeed, Statham obtained a certified letter from the North Carolina Comptroller's Office confirming his argument, stating:

I, William J. Clarke, Comptroller of Public Account . . . do hereby certify, in addition to my certificate of the 22nd of February last, respecting Thomas Mason; that I have very carefully re-examined the records respecting him, and that I am very clearly of the opinion that the payments were all made to one and the same man, and as certain as I can be without positive proof, which seems to me impossible, that there was but one man of the name. I further certify that a few Descriptive Sets of soldiers are on file in my office, and that they prove that free negroes served in the Revolutionary army, but that the payments as recorded make no mention of color by which I might be able to say whether said Mason was a negro or not.19

Thus, in light of the North Carolina record, Statham contended that "in the absence of any other applicant by this name as indicated by said Certificate, we deem it but just and fair to presume & claim, that he is the Thomas Mason whose widow we represent, provided, none other of that name is found in the same category."

Against the third objection, that the marriage had not been properly established, Statham asked, "what else must I do to prove the marriage when no records can be found?" Pointing out the unique legal and social situation of free blacks, he argued,

Recollect that the marriage of free persons of color are not kept with that attention which is paid to whites, and it is a rare case that one is ever returned by the Minister to the Clerk's office, as no law to fine him in that case exists, as is the case when he makes a failure to return the marriage of whites. Their marriage is therefore, seldom to be obtained from the records, though they generally get a minister to marry them, but he can do it without even the usual Clerk's certificate or license as is essential in the case of whites.

J. S. Pollard, Statham's assistant in Washington, wrote a similar letter explaining the difficulty of documenting the marriages of free blacks. In his letter to Commissioner Waldo, Pollard vouched for the authenticity of the Mason's marriage explaining:

In regard to the date of marriage of Thomas & Elizabeth Mason, it is equally impossible to produce any such testimony in the form of the kind required, but, moral reputation is shown, and that they raised a number of children & those of them now living are in old age & reputable. The degradation of people of color or tainted with African blood is so well known, in this country, as not to require us to say that their marriage relations are very little regarded among white men, and if married by even a Clergyman, as not obligatory upon to make a matter of record, yet the right of their descendants even in Slave holding States, to inherit & hold property is always recognized, notwithstanding there may be no statute laws of Virginia regulating their marriages, which we assume to be the fact.20

Pension Commissioner Waldo was not even aware, initially, that marriages were legal for free blacks in Virginia. On June 10, 1854, he sent a letter to Secretary of the Interior Robert McClelland, asking whether such marriages were legally recognized:

Sir: The application of Elizabeth Mason for pension under the Act of July 7th 1838, as the widow of Thomas Mason—the papers in which are herewith transmitted—presents the following question, which is respectfully submitted for your decision. . . . Can the relation husband and wife exist between free colored people in the State of Virginia—the ceremony of marriage taking place in said State, so as to constitute the wife, upon the death of the husband, his "widow," within the meaning of the laws of Congress, granting pensions to widows of deceased revolutionary soldiers? The importance of this question, together with the fact that I have not access to the laws and decisions of the Southern States, will, it is hoped, excuse the reference of this point to the disposition of the Department.21

Secretary of the Interior McClelland responded that "nothing has been discovered in the Statutes or "Code" of Virginia prohibiting marriage between free negroes or to deprive those who have entered into that relation, of any of the legal rights incident thereto—on the contrary, the rite of marriage is expressly recognized, and consequently legalized, between servants [slaves] and between a free person and a servant [slave]." McClelland added to his response:

I may not be amiss to call your attention to the Act of Assembly of Virginia, entitled "An Act for regulating and disciplining the Militia," of "May 1777 . . . that all free persons, hired servants, apprentices" &c were directed to be enrolled. The kind of service in which "free mulattoes" were to be employed designated and provision made against the enrolment [sic] of slaves, by requiring "any negro or mulatto" to exhibit a certificate of freedom to the recruiting officer before enlistment. It appears also by the same Act, that no distinction was made in the pay and bounty offered to such recruits."22

The rather trivial last objection by the Pension Office was that the petition declaration claimed service "in the Line of the Army" while the certificate from North Carolina showed only payments for "Militia service."

Many of the soldiers in the American Revolution were enlisted in state militia units, and the Pension Acts of 1832 and 1838, under which Thomas and Elizabeth had applied, covered all servicemen, whether they served in the Continental Line, state troops, volunteers, or militia. Statham argued that he had asserted from the very beginning "that the whole of her husband's service was in the militia, and that he volunteered the first time together with his whole company from Caswell County, North Carolina and went to Pennsylvania."

Any information contrary to that must have occurred in a subsequent draft that was written by Statham's assistant in Washington. An exasperated Statham concluded his letter, adding, "This claim has been suffered to stand unattended to for a great while, because free persons of color are but little noticed or cared for. Such claims are overlooked, and the testimony is more obscure, as they never have any acquaintances but those that live adjoining or near them. I hope on this account, that the Department will be as lenient as it can be with due regard to its interest and rules."23

The Value to Researchers of a Rejected Pension Claim

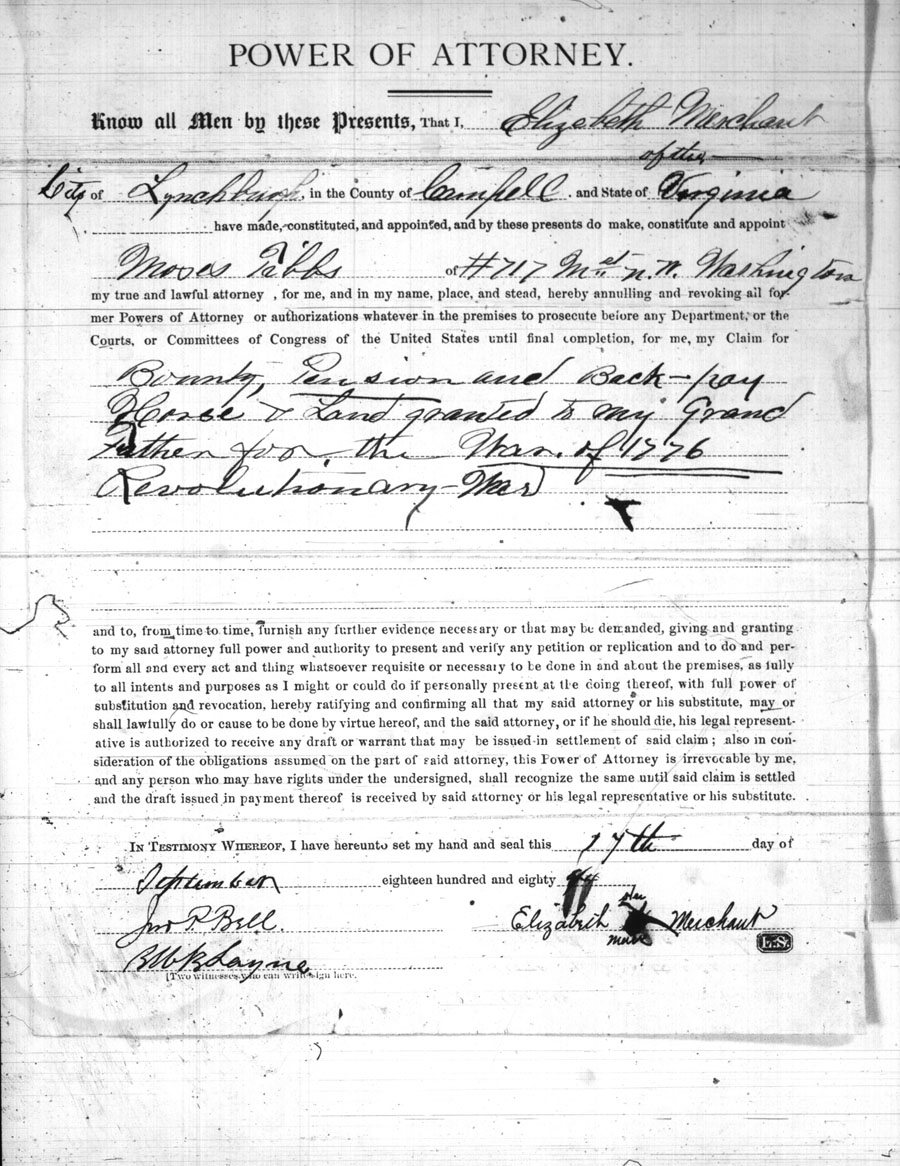

Elizabeth Mason passed away before ever receiving her widow's pension. About 30 years later in 1884, a granddaughter of the Masons, Elizabeth Merchant, of Lynchburg, Virginia, attempted to claim her grandfather's "Back-pay Horse & Land" owed to him as a Revolutionary War veteran. The Pension Office rejected Merchant's claim, explaining to her lawyer, a Moses Tibbs of Washington, D.C., that since neither the veteran nor the widow had been approved in the original petition, there was no obligation any descendants or heirs.

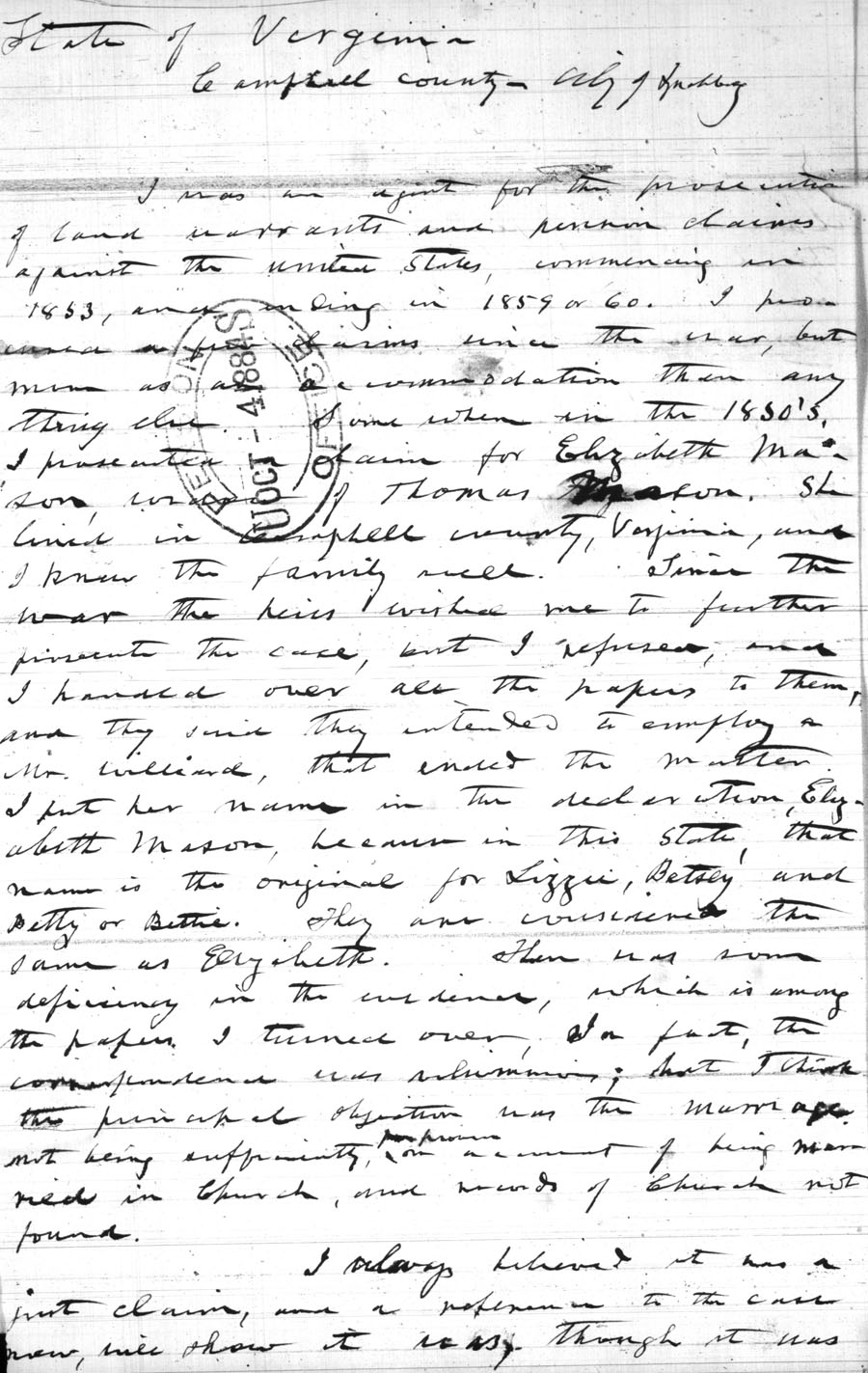

O.P.G. Clarke, the commissioner of pensions at that time, also contacted Elizabeth Mason's former lawyer, Charles W. Statham, to get more information about the old case. The now elderly Statham, explained that he believed that Elizabeth's denial was an injustice and perhaps a consequence of the charged political climate ascendant back in 1854 when the original claim was made.

Statham explained, "I always believed it was a just claim and a reference to the case anew, will show it as so, though it was difficult to prove the marriage of that class or race of people; for when I put in this claim, I knew of one or two that [had] been granted of that race, but before it was made the great political issue"—perhaps referring to the tense climate concerning race and slavery during the 1850s.24 Statham described the family, stating:

The soldier was a colored man of considerable standing, with property, married, and had a family, which he educated. He was married in Church according to the rights of the Episcopal Church; but the records and Church had gone down years and years ago. It was proven by the best citizens of the neighborhood, who had known them for many years, that they lived together as man and wife, had children, and were always recognized as man and wife, but it was not legally recognized, because our laws in regard to negro marriages were not respected. Since and after the [Civil] War, our District Military Commander issued an order pronouncing it a lawful marriage when they lived together as man and wife, and the Virginia Legislature passed as Act confirming the orders of the Generals.25

By that time, in 1884, Statham himself may have been a veteran, but of the Civil War. There is a Charles W. Statham listed as a lieutenant of the Lee (Virginia) Artillery in the Confederate army.26

Although her pension claim was rejected, a file such as Elizabeth Mason's is valuable for the glimpse it provides into the experiences of "persons of color" who served during the American War of Independence. Although no two pension files are the same, rejected pension claims often contain the most genealogical and historical information since the applicants were forced to argue their case and present additional information. For those who deserved the pensions, the rejections were a clear disservice. But the abundant information that can be found in such files is of great value to posterity.

Revolutionary War Records at the National Archives

Revolutionary War records are held at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and can be found in two main groups of records: the War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records (Record Group 93); and the Records of the Veterans Administration (Record Group 15).27 Most of the material relevant to genealogy can be accessed on microfilm and is also available online at genealogical sites, such as Ancestry.com and Fold3.com [formerly Footnote.com], and at the sites of organizations like the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR). The microfilmed records include Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804), which contains all of the contents of all the pension/bounty-land files; Selected Records From Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files (M805), which reproduces all records from envelope files containing up to 10 pages of records (but only significant genealogical documents from larger files are included); Compiled Service Records of American Naval Personnel & Members of the Departments of the Quartermaster General & the Commissary General of Military Stores Who Served During the Revolutionary War (M880); and Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War (M881).28

Researchers interested in the specific historical background of African American Revolutionary service can refer to The Negro in the Military Service of the United States, 1639–1886 (M858), which contains a compilation of published and unpublished primary sources along with a few original documents and extracts of material from secondary sources. The National Archives also published, Special List No. 36, List of Black Servicemen Compiled From the War Department Collection of Revolutionary Records (1974). The NSDAR has also compiled a valuable collection of sources and related information in their volume Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War (2008).

Damani Davis is an archivist in the National Archives Research Support Branch, Customer Services Division, Washington, D.C. He has lectured at local and regional conferences on African American history and genealogy. He is a graduate of Coppin State College in Baltimore and received his M.A. in history at the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio.

Notes

1 Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1880–1900 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804), roll 1647, frames 622–676.

2 In this essay the term "Patriot" is used as a proper noun to designate colonists who supported American independence.

3 This change in American policy with regard to African American recruitment can also be seen as a strategic countermeasure against the British Army's efforts to recruit blacks. Larger numbers of blacks actually joined the British forces as opposed to the Patriot forces, and this was especially true in the southern states. The Black Loyalists were motivated to join the British as a means of achieving or securing their own freedom in response to the widely announced proclamations by Gen. Henry Clinton and John Murray, Earl of Dunmore.

4 See Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: 1961); Gary B. Nash, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge, MA: 2006); and Noel B. Poirier, "A Legacy of Integration: The African American Citizen-Soldier and the Continental Army, " Army History (Fall 2002).

5 Nash, The Forgotten Fifth, p. 10.

6 Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution, p. 56.

7 Ibid., p. 67; Many enslaved blacks in the South, especially in South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, would actually respond to the British offerings of freedom for service in their ranks.

8 Ibid., pp. 56, 58.

9 Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to About 1820 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2005), vol. 2, p. 816.

10 These surnames may possibly refer to North Carolina militia officers Capt. William Wilson and Col. William Moore.

11 Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, M804, roll 1647, frames 622–676.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid., frames 649.

14 Ibid., frames 657–658; 668–669.

15 Ibid., frames 653–656.

16 Ibid., frames 674–675.

17 Ibid., frames 634–637.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid., frames 647.

20 Ibid., frames 640–642.

21 RG 48, Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior, Patents and Miscellaneous Division, Entry 248 Reports of the Commissioner of Pensions Concerning Appeals, 1849-1881. (ARC ID 721409).

22 Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, M804, roll 1647, frames 643–645.

23 Ibid., frames 634–637.

24 Ibid., frames 651–652.

25 Ibid., frames 659–660.

26 Francis Augustin O'Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock (Baton Rouge, LA: 2006).

27 Most of the records of the American Army and Navy in the custody of the War Department were destroyed by fire on November 8, 1800. Further losses occurred in August 1814, when British troops burned government buildings in Washington. From 1873 to 1914, the War Department purchased and collected Revolutionary War records from private institutions and individuals and from other state and federal agencies.

28 Other relevant National Archives microfilm publications include Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775–1783 (M860), and Index to Compiled Service Records of American Naval Personnel Who Served During the War (M879).