Let the Records Bark!

Personal Stories of Some Special Marines in World War II

Winter 2011, Vol. 43, No. 4

By M. C. Lang

Requests for copies of records relating to military service come into the National Archives every day. Some people are trying to fill in family history; others are looking for documentation of their own service. Those who need records of service from World War I and later are directed to our National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri.

Unless they're talking about a dog. Specifically, a World War II Marine Corps dog. At the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, are 11 small boxes containing the individual Dog Record Books of each canine who enrolled in the Marine Corps from December 15, 1942, to August 15, 1945. Two more boxes hold the record books of another 132 dogs that were transferred from the Army into the corps.

The general history of the Marine Corps's use of dogs during World War II and subsequent conflicts has been told several times and is the subject of at least one book. Studying original records, however, is a very different experience from reading a secondary source, no matter how authoritative it may be.

When browsing original records, one is engulfed by the tiny details and individual stories that are invariably lost in the large murals painted by historians. But these miniatures are worth looking at, since they may offer the viewer small realities that can be enlightening, amusing, poignant, and memorable.

Each Dog Record Book is about 4" x 6" in size and 40 pages in length. A new book was opened for each dog "when he (she) first report[ed] to the Dog Detachment Training Center for duty." In making entries, "neatness, clearness, and strict economy of space" was expected to be observed, and each book had to be returned to the Dog Detachment Training Center at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, when the dog was "separated from the service," which explains how these little documents came to be preserved.

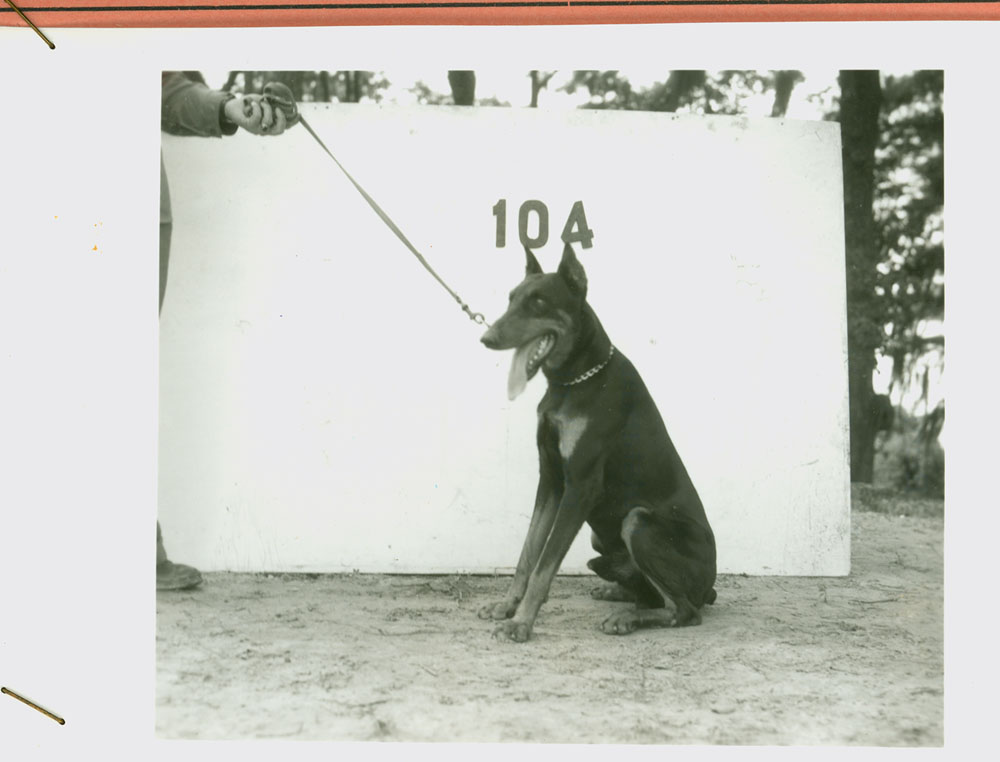

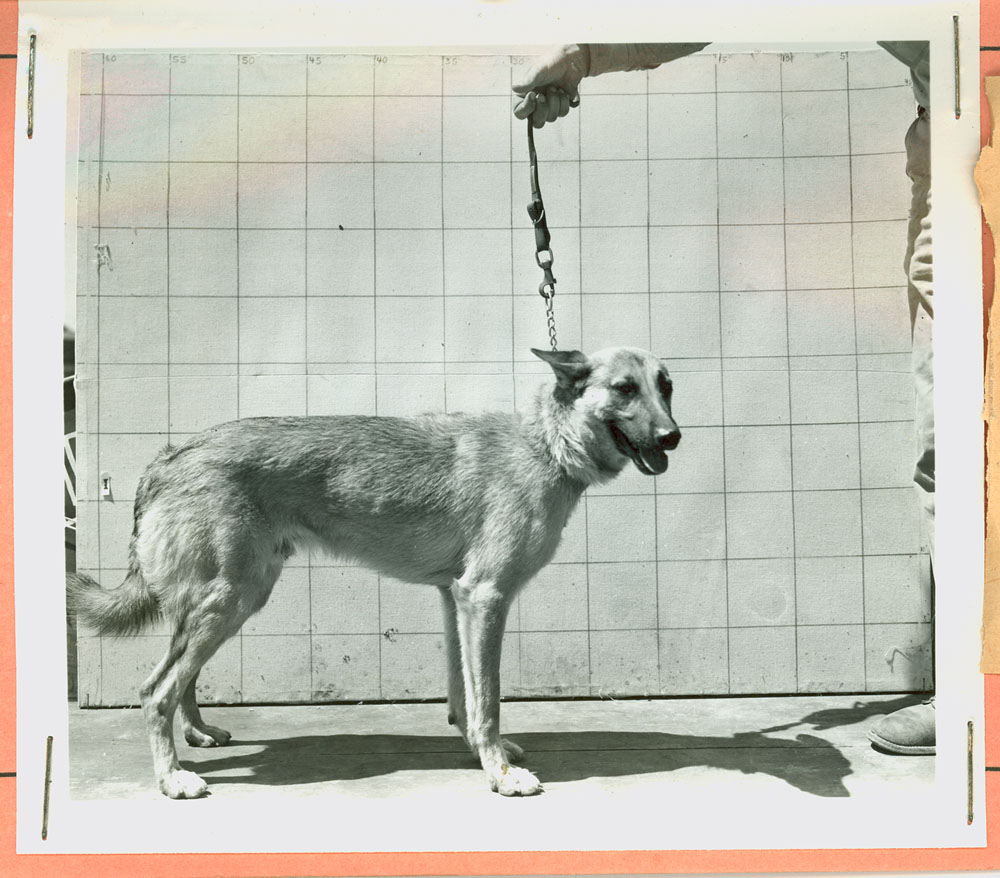

In addition to the usual personal details (full name, "call" name, sex, date of birth, date of enlistment, etc.), each book had separate sections for 1) Training Qualifications, 2) Notes on Training, 3) Record of Transfers, 4) Record of Custody, 5) Medical History, 6) Professional History, 7) Promotions, 8) Letters of Commendation, 9) Citations, and 10) Discharge Certificate. In many instances, a photograph of the dog was stapled to the inside back cover. In some cases, upon promotion of the dog to the rank of sergeant, a second and more formal photo was taken and placed in the book.

"Royalty" Represented in Ranks of Dogs of the Marine Corps

Each Dog Record Book contained both the new marine's full name (on the front cover) and call name (on page 1). At least in the beginning, this definitely was not a distinction without a difference. Among the earlier enlistees are Arno of Ochsnerhof (Prince), Baptiste Courageous (Boy), Sir Knight of Northwood (Max), Ektar of Pontchartrain (Kathe), Hertha von Hayes (Herth), Peppo von Ludwigsburg (Peppy), Bodonna Lady von Palanka (Bodie), Arthur B. Shelton (Biddie), Jacques du Nord (Jack), Elsa von Stahlhelm (Gretel), Kirt of Montgomery (Duke), Eric the Red von Strumwind (Clipper), and Eleanore's War Girl (Missy).

As time went on, the difference between full name and call name gradually diminished, and after serial number 150 or so, we find the distinction between them virtually gone, with most names being short and simple: Marie, Tammy, Rex, Kurt, Sig, Dud, Bill, Gus, Jeep, Pal, Karloff, Semper, Fidelis, Iwo, and Jima, for example.

Some names were far more common than others. To stand at a modest distance from a large group of war dogs hanging around during a break and call for "Duke" was to risk being trampled by a herd of furry marines. There were no fewer than 57 Dukes enlisted in the corps, starting with serial numbers 4 and 5 and ending with the last enlistee of all—serial number 892.

Aside from Dukes, other royalty were represented to lesser degrees: there were 41 Kings, 36 Princes, 7 Barons, 3 Duchesses, 2 Counts, and 2 Princesses but only 1 Queenie. Among the military there were a few Colonels, Majors, and Captains, but only one Eisenhower and McArthur (neither of whom, incidentally, came close to achieving the renown of their namesakes). And ironically, the ultimate warrior's name—Achilles—was borne by a Doberman found "not sufficiently rugged mentally or physically for War Dog [duty]."

Achilles was one among a number of enlistees who, upon arrival at Camp Lejeune and after a period of evaluation, were rejected for active service. A number of the record books contain only two entries under the record of transfers section: "Joined" followed by "Rejected." A common reason for rejection was "unsuitable temperament," which was sometimes more fully explained: Kodiak was "too sluggish"; Fiddler "too queasy for combat"; Klaus could not be trained "because of viciousness toward other dogs & his handler"; Nome had a "nervous temperament bordering on hysteria"; while Chief was "noisy with gunfire."

Gretel, on the other hand, was "too gentle and unalert"; Leo was "congenitally treacherous"; and Skipper was even worse—"This dog was an incorrigible fighter of other dogs and congenitally vicious and treacherous." Unfortunately for Skipper, his former owner did not want him back, and the training notes in his book state that "Former owner gave authority in writing to make such disposition of him as seemed fit. Accordingly, dog was humanely destroyed by Veterinary." Donna, on the other hand, was a "very gentle dog—too much so for war dog work." She also suffered from "chronic tender feet," but unlike Skipper, Donna was returned to an owner who took her back, tender feet and all.

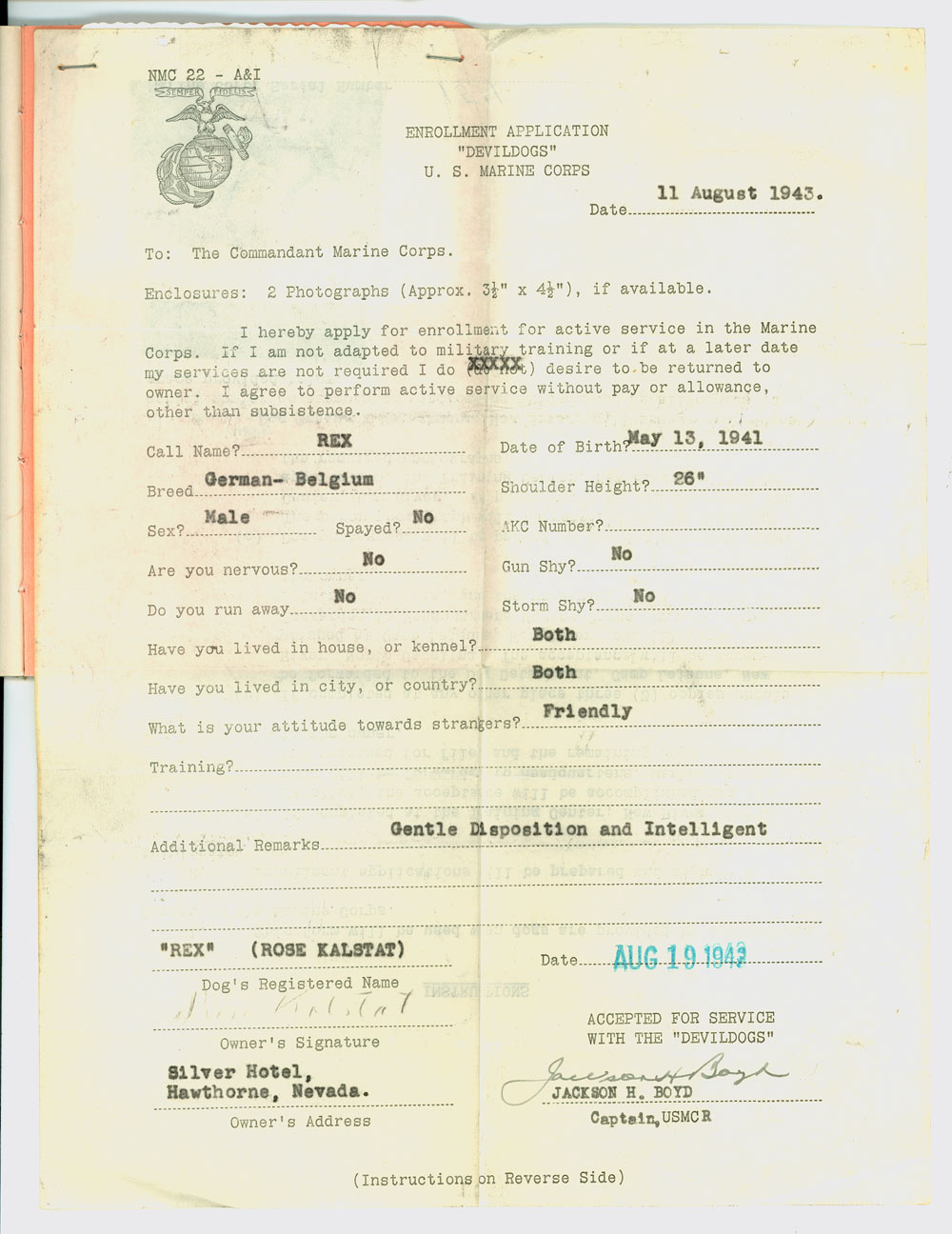

Applicants Had to Complete Personality Quiz to Serve

How each dog found his or her way into the Marines is not normally revealed in the record books. However, folded into the book of one Rex, a German-Belgium shepherd, was his original enrollment application, addressed to the Marine Corps Commandant and dated August 11, 1943. Although the form does contain the signature and address of Rex's owner, it is clearly designed to be the dog's application, commencing with the statement:

"I hereby apply for active service in the Marine Corps. If I am not adapted to military training or if at a later date my services are not required I do (do not) desire to be returned to owner. I agree to perform active service without pay or allowance, other than subsistence."

Then, in addition to providing various basic personal details, each applicant was required to provide answers to a number of personality-focused questions, including: "Are you nervous?" "Gun Shy?" "Storm Shy?" "Do you run away?" "Have you lived in house, or kennel?" "What is your attitude toward strangers?" The only thing lacking is a short essay explaining the applicant's reasons for wanting to join up.

Once accepted for service, the dogs went to the Dog Detachment Training Center at Camp Lejeune, where they were qualified in obedience and at least one other specialty. The record book lists the following possibilities: Guard Duty, Tracking, Attack, Messenger, First Aid, or Draft. In fact, however, most Marine dogs were used for messenger or scouting work.

In the "Notes on Training" section, the earliest entries in each dog's book frequently describe his or her most dominant traits, for better or worse. Some of these notations were intended to be of use to future handlers, while others were more personal in nature. "Rolo (#16) is a high spirited dog of medium size, requiring a firm hand in handling"; "Otto is . . . one of those dogs who never fatten up. He is very intelligent, is a good point dog and very well trained"; "Andy is a dog . . . of stable temperament. Because of his graceful gait and bearing, he was called 'Gentleman Jim'. Although very mild and affectionate, he was one of our best attack dogs."

Cappy's notes warned future handlers to "Be careful of this dog when under gun fire—he is timid" and "This dog is gun shy. Not fit for combat duty." Cappy, however, obviously found his niche, since the professional history section of his book states "This dog was on 6 combat patrols and was used for nite security during the entire Guam operation."

Pal's training notes record some very special instruction he received: "This dog was very high strung and nervous. He was also inclined to be gun-shy. He was broken of this at New Caledonia by taking him out in a boat and firing rifles. At first he jumped out of the boat, but he finally got so played out by swimming that he remained in the boat when rifles were fired. This procedure was followed 2 more times at later dates."

And here's the considered evaluation of one obviously popular Doberman: "Sparky is a good big sound dog with a happy-go-lucky personality. He has a world of energy and never seems to lose weight. He is the clown of the platoon."

Records Reveal Problems Resulting from Combat

Later entries in the training notes often record issues arising after the dog had been in combat. For example, upon arriving in the South Pacific, Eri was not only made nervous by gunfire, but he also had a "habit of trailing frogs, birds, etc. Whenever he hits a trail he will bay and make a great deal of noise." This was not a career-ender, however, since "while waiting for transfer back to States, Lanley and Mahoney [human handlers] started to work Eri out as a messenger dog. Eri soon showed promise and was therefore kept in the platoon."

Some dogs developed shell shock: Duke (#21) "was a very good dog when he arrived at Bougainville. However after doing an outstanding job with his trainers . . . he became shell shocked and never did good work from then on." Ruff, who "because of her affectionate and intelligent personality . . . made a good Red Cross dog" and whose "record of achievement in combat may be found in the Journal of Operations of the 2nd Marine Raider Regt. (Prov.)" was subsequently "found unsatisfactory for combat . . . due to a nervous condition from shell fire" and returned to her former owner.

Judy had an almost identical personality and career path: "Judy was a fast bitch with a loveable and affectionate personality. She had an ideal temperament for a Red Cross dog," but after several months in the same outfit as Ruff, "Judy was found unsatisfactory for further combat work due to a nervous condition due to shell fire" and also returned home.

Otto, the intelligent, well-trained, and good point dog mentioned earlier, subsequently developed "a nervous condition as a result of shell fire. But he did work out very successful [sic] before this condition developed." Sadly, Otto's notes then record that he was destroyed on July 20, 1944, at Camp Lejeune "by direction of CMC Ltr. #28137B [dated] 13 July 1944."

Shell shock was not the only danger these dogs had to face. The professional history sections record the deaths of several dogs due to "combat fatigue," including Dutchess, who "died on Guam, April 17, 1945," and Eric, who "died on Iwo Jima 7 April 1945."

Professional Histories of Dogs Recorded Deaths in Action

Rolo (#16), whose training notes were quoted earlier, and whose professional history section ends with the statement that "The record of his achievements in combat may be found in the Journal of Operations of the 2nd Marine Raider Regt. (Prov.)," was "killed in action against Jap machine gun emplacement on December 24, 1943." In the very same action, one of Rolo's trainers, Pfc. Friedrich, was declared "missing in action," and his other trainer, Pfc. White, was "wounded but not serious."

Tam contracted pneumonia while on board ship traveling from Guadalcanal to Guam and "was buried at sea," while the fate of Dale remains unknown: "Dale 332, landed in enemy territory on 19 February 1945. Immediately upon landing the dog became uncontrollable and would not respond to any commands—the dog broke loose from his handler and ran from the beach—Due to the gunfire encountered on the beach it was impossible to recover the dog—no member of the 7th war dog platoon ever saw Dale 332 during the operation."

And Kathe (#58), who made it through months of combat, died in April 1944 "of toxemia from eating a dead crab picked up while exercising." Prior to her death, Kathe, while stationed in New Caledonia, apparently spent some time fraternizing with the local population, since her record book notes she "whelped 10 pups—4 males, 6 females—sired by 'Gunga Din' (a native dog). Pups were given away to various servicemen."

Kathe was not the only marine who enjoyed a full social life while on active duty. Girlie, who enlisted in January, 1943, became the proud mother of three boys and two girls in August of that same year. Her medical history page notes "Mother & pups in good health." The father, of whom no mention is made, was undoubtedly a comrade in arms.

The professional history section of each book was the place to record the dog's participation in "Expeditions, Maneuvers, Engagements, Special Events, etc." Some handlers took the time to make detailed entries in this section, but in many cases there is little or no information or simply a statement that the dog's "achievements in combat may be found in the Journal of Operations."

One dog's entry reads in its entirety: "War dog Emmy was on 3 combat patrols during the Guam operation. Missing in action while on patrol."

Another relates, "War dog Cookie was on one combat patrol. While on nightly security duty during the Guam operations this dog alerted [i.e., alerted her handler to the presence of] 10 Japanese soldiers, six of which were killed. This dog carried a vital message from an out-post to the division CP, of which there were no other means of communication."

Honors Awarded to Dogs for Service in Action

Rollo (#45) had a career that extended beyond the war. His history states that he not only "participated in the taking and occupation" of various islands from April to July 1945 but subsequently, in 1946, at "Catoctin Recreational Demonstration Area, Thurmont, MD," an area that includes what is now called Camp David, "Rollo served as a member of the detachment guarding the President of the United States." Rollo, it should be noted, was promoted to platoon sergeant effective April 8, 1946, by written order of Col. Donald J. Kendell, commanding officer of the Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C.

Promotions, recorded on a page designated for that purpose, were earned as the result of time in service. It took three months to become a private first class, one year to make corporal, two years to sergeant, three years to platoon sergeant, four years to gunnery sergeant, and five years to become a master gunnery sergeant. Since the first dog enlisted in December 1942 and the last dog in August 1945, it's not surprising that the highest rank achieved by any dog in the record books was platoon sergeant.

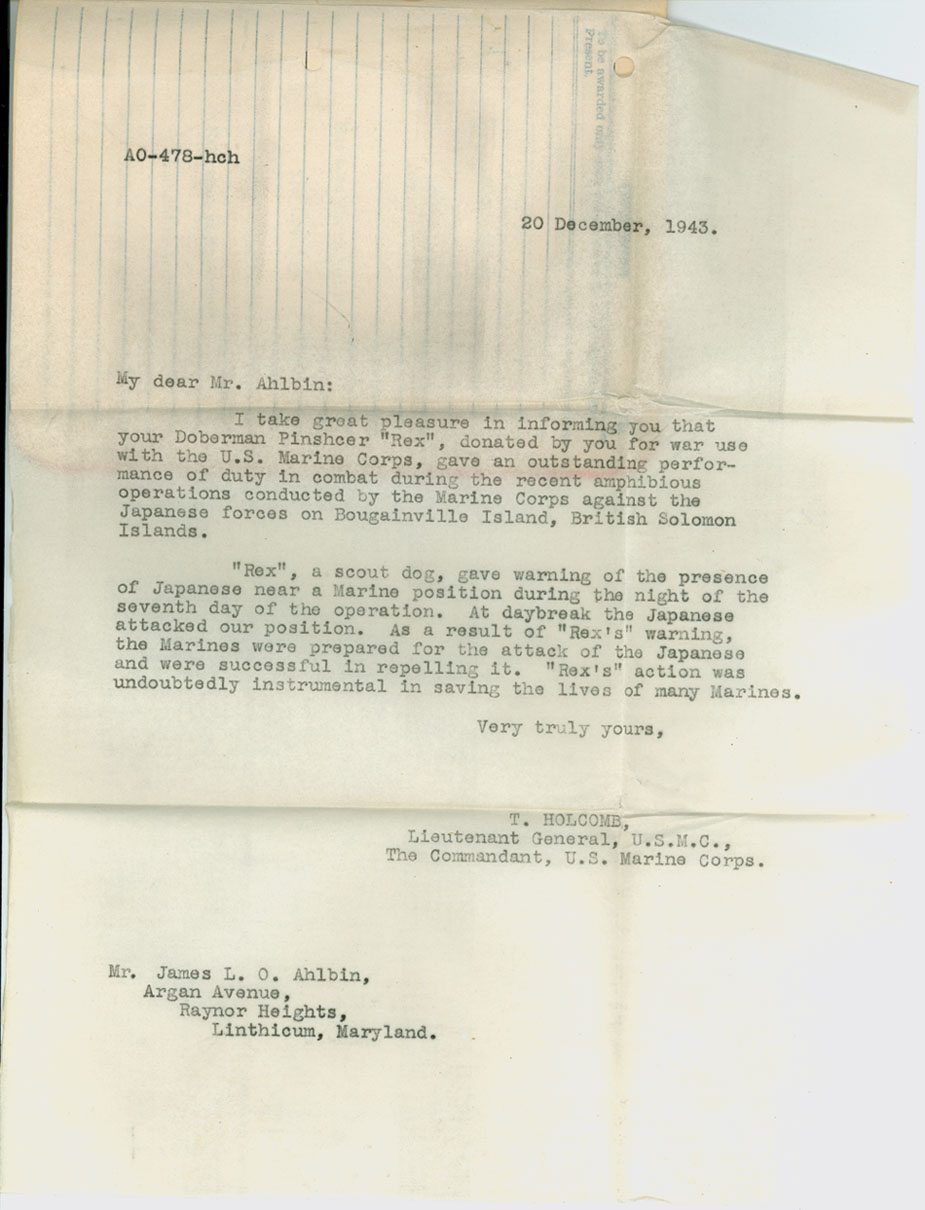

Although the books provide space for letters of commendation and citations, these sections are frequently blank. Occasionally a notation is found like this one in Otto's book: "Wounded on 4 Nov. Recommended for citation comparable to the Purple Heart." Although canine marines could not be awarded decorations for which their human counterparts were eligible, acts of valor were not ignored. Folded into Rex's (#26) book was a copy of a letter dated December 20, 1943, addressed to his original owner, commending Rex's "outstanding performance of duty in combat" on Bougainville Island, when he gave warning of the presence of Japanese soldiers. The letter, signed by Lt. Gen. T. Holcomb, Commandant of the Marine Corps, concludes that "As a result of 'Rex's' warning, the Marines were prepared for the attack of the Japanese and were successful in repelling it. 'Rex's' action was undoubtedly instrumental in saving the lives of many Marines."

At the back of each record book is a printed discharge certificate, along with three possible reasons for discharge: "Expiration of Enlistment," "Wounded in Action," or "Killed in Action." Other reasons, which were written in when needed, included "Missing in Action," "Died" [from other than combat-related injuries], or "Transferred to the Army." On the reverse, each discharge was classified as "Honorable," "Regular," or "Dishonorable," and the dog's character was rated as "Outstanding," "Excellent," or "Very Good."

A Bond Is Established Between Dog and Marine

The vast majority of dogs received an honorable discharge, accompanied by a character rating of excellent. A much smaller number achieved the highest rating of outstanding, including Rolo (#16), mentioned earlier, who was killed in action. Rolo's discharge certificate was signed on December 24, 1943, by Lt. Col. Alan Shapley. Just over two years before penning that signature, then-Major Shapley was on the USS Arizona as it lay in port in Pearl Harbor, and he was one of only a handful of marines who survived the Japanese attack that sank the ship. One can only wonder if, when he picked up Rolo's book, Shapley took notice of the dog's date of birth: December 7, 1941.

A random review of the record books turned up one dishonorable discharge, accompanied by a character rating of "Unsatisfactory." This was, not surprisingly, in the book of the aforementioned "congenitally vicious and treacherous" Skipper.

After being discharged, many dogs were returned to their original owners. If the original owners could not be found, or if they no longer wanted the dog back, new owners were sought. In more than a few cases, the dog's Marine Corps partner/handler stepped forward and assumed formal ownership. Before taking possession of their dog, the original or a new owner had to sign "Legal Form D," found stapled inside the front cover of some books. In this formal notarized document, the owner 1) acknowledged they had "been informed by the U.S. Marine Corps, and fully understand, that the training for military service which this dog has undergone is likely to have made him intractable and wholly unsuitable for life with a private family and that he may have acquired aggressive qualities which may cause him to attack people without provocation"; 2) assumed full responsibility for controlling the dog and for any injuries or damage done by the dog after discharge; and 3) indemnified the United States for any amounts it might be required to pay, as the result of a court decision or private settlement, to any person injured by the dog.

At this point the record books fall silent. The postmilitary careers of all these dogs remain unknown. One may speculate, however, that most of them continued to give to their owners, old or new, the loyalty and devotion they demonstrated while on active duty. Although the postwar bond between civilian dog and owner might perhaps equal that which existed between Marine dog and handler, it could never surpass it.

Every once in a while the record books, through some tiny detail, provide a glimpse into the depth of the unique wartime mutual dependence between dog and man, in which the life of each often hinged on the reliability of the other to do his duty. On March 18, 1944, Andreas von Wiedehurst, the Doberman called Andy, who you may recall was nicknamed Gentleman Jim, was on Guadalcanal when he was "Struck by truck at 10:00 a.m., back broken & crushed internally." The very last entry in Andy's record of transfers reads "DIED at 10:20 a.m." That may not seem to say very much, but its unnecessary precision implies a great deal. It suggests with a high degree of certainty that some marine stayed with Andy to the end and was at his side to note when he took his last breath. The loyalty that flowed from dog to man during Andy's active service was indeed reciprocated and is memorialized in a little Dog Record Book now resting on the shelves in the National Archives.

M. C. Lang is a volunteer in the Textual Records unit (Modern Military Records) at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. He earned an A.B. in Ancient Greek from Hamilton College and a J.D. from N.Y.U. School of Law. Retired from active legal practice, he currently serves as a mediator in the D.C. Superior Court.

Note on Sources

The Dog Service Record Books found in Record Group 127, Records of the United States Marine Corps, located at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, were the sole source material used in the preparation of this article. For those interested in the subject, a relevant published book is William W. Putney's Always Faithful: A Memoir of the Marine Dogs of WWII (New York: Free Press, 2001).