Fireworks, Hoopskirts—and Death

Explosion at a Union Ammunition Plant Proved Fatal for 21 Women

Spring 2012, Vol. 44, No. 1

By Jay Bellamy

War is an industry, creating jobs for those willing and able to fill them.

As the Civil War was being fought on battlefields such as Manassas, Fredericksburg, Antietam, and Gettysburg, ordinary citizens in both the North and the South were doing their part to help achieve victory for their side.

While it was thought that danger awaited only those wearing the uniforms and carrying the guns, death is indiscriminate and can strike anywhere.

In June of 1864, a tragedy so devastating that it moved both President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to become involved occurred in Washington, DC. The following is a description of that tragedy and its aftermath.

June 17, 1864, was another dreadfully hot day in Washington, DC.

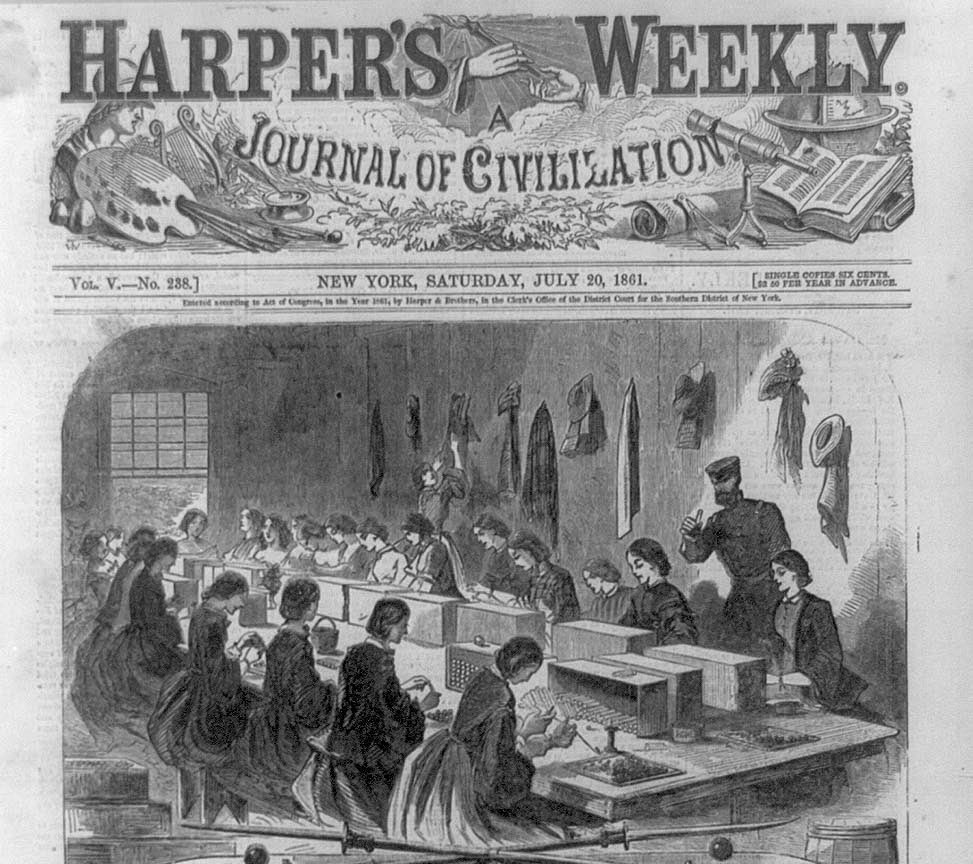

At the U.S. Arsenal laboratory, located on the site of present-day Fort McNair, approximately 100 young women were busy at work assembling small arms ammunition for the Union war effort.

Young women and teenage girls, some as young as 13 years old, were often selected for this kind of work, as it was believed their smaller fingers better enabled them to pack the ammunition once it was assembled. Many of these workers were children of Irish immigrants, who found it necessary to send their children off to earn the small wages these jobs provided.

Working conditions at the arsenal were less than ideal. With black powder spread throughout the building, it was only a matter of time before disaster would strike.

In fact, less than two years earlier, an explosion had taken place at the Alleghany Arsenal in Pennsylvania, prompting the Washington workers to take up a collection for their fallen comrades. It was the strangest of accidents, caused by a spark ignited when a horse’s hoof struck a stone. The spark set off a series of explosions that led to the deaths of 78 people. Like the Washington Arsenal workers, many of these victims were girls and young women no older than 20 years of age.

But if these women ever thought about the danger involved, it did not deter them from their work. The war was still raging, and it was important for the soldiers to have the ammunition they needed to fight.

Although grateful for the wages—pitiful as they may have been—many of these women probably felt an even greater pride in knowing they were contributing to the war effort. The United States was their adopted homeland, and now they were being given the opportunity—if not the privilege—to do something to show their gratitude.

Long Hoopskirts Help Spread the Fire Quickly

On this hot Washington day, these young women and children quietly went about their assigned duties.

Earlier that morning, one employee was dismissed for laughing and talking at her work station, prompting her to complain about her misfortune to an older co-worker before departing the building. Her colleague, unaware of the great part fate was soon to play in the young girl’s life, told her that perhaps her dismissal would turn out for the best.

As the remaining workers sat at their workstations assembling the many cartridges that, when completed, would be packed inside ammunition boxes and sent to the front lines, the temperature outside was nearing 100 degrees. The temperature inside the arsenal was even greater. Contributing to the women’s discomfort were the long hoopskirts and long-sleeved blouses that made up the typical employee’s work clothes.

The building in which they were working was divided into five sections, the last of which was the “choking” room. “Choking,” the final step in the processing of ammunition, involved using a machine to fasten the end of a cartridge to a ball. Outside the building on the ground were three pans of fireworks, possibly for use in the upcoming Fourth of July celebrations, foolishly set out by the superintendant, Thomas B. Brown, to dry.

At 10 minutes to noon, after the fireworks had been sitting in the sun for three to four hours, a large explosion was heard, and a column of smoke quickly filled the clear blue sky. The hot June sun had ignited the fireworks, sending streamers of star pellets through the air.

Because of the heat inside the building, a window in the “choking” room had been left open for ventilation, and through this open window a flaming pellet entered and traveled down the countertop, setting fire to the cartridges the women were handling. At the end of the work table sat a barrel of gunpowder, which ignited when the pellet reached the end of its travel, lifting the roof off the building and filling the room with smoke and flame.

Pandemonium ensued.

Those lucky enough to have survived the initial blast ran for the doors and windows, many with the bottoms of their hoopskirts ablaze. As they rushed past terrified co-workers, their skirts would touch, resulting in a domino effect of flaming hoopskirts.

Others who survived the blast found their escape hampered by the heavy benches that trapped them against their workstations. Likely screaming for help, their pleas went unanswered as each woman attempted to make her own escape from the heat and flames. With the oxygen in the room being consumed by the fire, these women would perish within minutes.

At the sound of the explosion, some of the male employees of the arsenal came running in from outside, carrying tarpaulins to extinguish the flames the escapees carried with them. Some of these young men suffered serious burns of their own.

Other girls were scooped up and rushed to the nearby Potomac River, where they were dunked into the water in an effort to save their lives. Three women, possibly delirious and uncertain of their surroundings, started running up the hill—their clothing in flames—but they were quickly intercepted by two men who ripped off the upper part of their clothing, most likely saving them from a certain and agonizing death.

Others managed to find their way to the dock, where they were then placed aboard a government steam tug and transported to the Sixth Street wharf. There, they were handed over to friends and family members who took them home to nurse their wounds.

Searching for Survivors In the Carnage of the Fire

Once the flames inside the building were extinguished, the search for possible survivors began.

As rescuers entered, the carnage was immediately apparent. Found inside were the charred remains of those who had been killed in the initial blast, many missing arms or legs or both. Some bodies were so badly burned that if one were to try to lift the corpse, it would have fallen apart at the touch. As reported in the Washington Star that afternoon: “The bodies were in such a condition that it was found necessary to place boards under each one in order to remove them from the ruins.”

Some victims could only be identified by a piece of clothing still clinging to what was left of the body; others could not be identified at all. In all, 21 workers died in the initial blast or shortly after being pulled from the smoldering building still alive.

Almost immediately upon learning of the tragedy, the normally stone-faced, some say cold-hearted, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered that all expenses related to the funerals be paid for by the War Department, telling the commandant of the arsenal, “You will not spare any means to express the respect and sympathy of the government for the deceased and their surviving friends.”

The responsibility for planning and carrying out the funeral arrangements was given to the arsenal workers as a way for them to show their respects and personal condolences. It was decided to hold the services on June 19 on the very site where these young women had given their lives for their country.

When mourners arrived on the grounds of the arsenal that Sunday, they found 15 finely crafted coffins constructed by the arsenal’s carpenters sitting side by side on a wooden pavilion built by the master carpenter.

(Four of those killed in the explosion had been buried at Mount Olivet cemetery the previous day; one was receiving her final rites at home; and the sixth would succumb to her injuries three weeks later. She would be buried alongside her co-workers in Congressional Cemetery on July 6.)

Each coffin contained a silver-plated plaque listing the victim’s name; for those who could not be identified, the plaque simply read “Unknown.” The sister of Melissa Adams, one of the unidentified, became so distraught that when she went looking for her sister’s coffin on the platform, she collapsed when she was unable to find it.

Lincoln in Funeral Procession As Just Another Mourner

In attendance that afternoon were President Abraham Lincoln, dubbed by the press as the “mourner in chief,” and Secretary Stanton.

At 3:15 p.m. the funeral procession—which by some estimates included nearly 150 carriages and stretched for nearly a mile—left the grounds of the arsenal and began its journey toward Congressional Cemetery. After private family services, the coffin containing the body of 13-year-old Sallie McElfresh joined the procession once it reached F Street. Lincoln’s personal carriage followed behind the hearses carrying the remains of the other victims.

Once they reached the cemetery, the coffins were divided into two groups. Those who were able to be identified were placed inside one mass pit, while the unidentified were interred in another located just six feet away. Each pit measured 15 feet wide and 5 and a half feet deep.

The remains of McElfresh and Annie Bache were buried in nearby family plots. Lincoln was not asked to and did not speak at either the arsenal service or at the graveside.

If he had spoken, he probably would have honored these women in a manner similar to that which he had done at Gettysburg the previous year, when he was asked to deliver a “few appropriate remarks” to honor those who had died on the battlefield. He probably would have spoken of the need—as he would in his second inaugural address in March 1865—“to bind up the nation’s wounds” so that tragedies such as this would never again occur.

But on this day he was simply a mourner along with the many other mourners who had come out to pay their final respects to these innocent victims of war. As the coffins were being lowered into their graves by the male arsenal workers, the crowd began to chant “Farewell, sisters, farewell.”

Officials Give Their Accounts As Coroner Reconstructs Tragedy

When Dr. Woodward, the coroner for the District of Columbia, showed up on the scene of the tragedy around 4 p.m. on the day of the accident, he immediately summoned a jury of inquest to hear testimony in the case. After viewing the remains of the victims, the jury was then sworn in and the proceedings began.

The first called was Brown, the superintendent. He was asked if he recognized any of the remains. He said he did not, but he believed one of them to be a young woman by the name of Bridget Dunn; he based his conclusion on the size of the corpse, as Dunn was of larger size. (She would be one of the four buried in private ceremonies on June 18.)

Although he claimed to have no knowledge as to how the explosion might have occurred, he did admit to leaving white and red star fireworks lying in three pans some 30 to 35 feet from the window of the “choking” room. The white star fireworks, he explained to the jury, contained no sulphur—a highly combustible element. He further stated that he had left fireworks out in the sun before—even in August—without any negative consequences.

After Maj. James G. Benton, the commandant of the arsenal, showed the jury one of the pans containing a white deposit on the bottom—proving that an explosion had taken place in the pan—Brown then listed the ingredients of the red star fireworks, which included black antimony.

When one of the jury members mentioned that black antimony contained sulphur, Brown explained that he used a composition of his own when making fireworks and that he considered his own concoction to be far less dangerous.

The next person called was the commandant, Benton himself. He told the jury that he had not been present at the time of the explosion but arrived soon afterward to help prevent the spread of fire to nearby buildings. He said that after inspecting the pans left out by Brown, he was able to determine that the explosion had originated in those very same pans.

He explained that when assembling ball cartridges, the points of the balls would be facing toward the body and it was his opinion that some of the arsenal workers may have been killed after being struck by the exploding cartridges.

Benton admitted to having warned Brown on many occasions to be careful—not because he was careless but simply out of general concern—but he believed Brown’s negligence was simply an oversight and not due to any criminal behavior. Benton said that although he believed Brown was a careful man in general, leaving combustible material lying outside in a heat absorbing pan was certainly an unwise decision on his part.

Some of the Women Died from Exploding Cartridges

Henry Soufferle, an arsenal employee, was called next. He stated that while looking toward the south end of the building he saw a flame enter the window of the “choking” room, at which time he shouted out to warn the young ladies working there.

The flames spread quickly, and Soufferle left as quickly as possible, pushing two women who were washing their hands on the porch out of the way before the flames could reach them. He told the jury that he had noticed the pans containing the stars earlier that morning but was unable to locate them after the explosion.

Next up was Andrew Cox, Brown’s assistant. He stated that he was talking with Brown and Maj. Edward Stebbins when the alarm sounded. At first he thought the explosion had occurred somewhere else, but he took off running when he realized it was his own building. He, too, testified to having seen the three pans of fireworks earlier that morning.

On a blueprint of the building, he pointed out where each of the girls in the “choking” room was seated. He told the jury that each employee had approximately 500 cartridges to work with, each containing 70 grains of powder. Like Benton, he also mentioned that the points of the ball cartridges would have been facing toward the body of the employee assembling them, again implying that some of the young women may have been killed by exploding cartridges.

The paymaster and military storekeeper, Stebbins, was next. He testified that while sitting at the work table he noticed through the open window something flying about the air. Just as he exited the door to investigate, the room became engulfed in flames. (The explosion occurred after the fire ignited.)

He testified that upon reaching the outside, he realized that what he had seen were firework “stars” and that some may have even reached the river, some 40 feet away. He then threw open the doors to allow those inside an opportunity to escape, using a tarpaulin to extinguish the flames that clung to the skirts of many of the workers as they made their way out of the building. He then stated that he did not believe any of the young women sitting on the south side of the bench would have been able to free themselves from their seats before the fire consumed them.

The last witness called was Clinton Thomas, who worked in the gun carriage shop. Thomas testified that he was looking directly toward the laboratory building when the fire and explosion occurred. He claimed to have seen fireworks explode from behind the building and thought at first that Brown was setting them off. The next thing he knew the building was engulfed in flames.

Jurors Reject Further Witnesses; Commandant Files His Report

At this point the coroner informed the jury that there were others available to testify, but the jury insisted they had heard enough to reach a fair and proper conclusion.

After deliberation, the jury announced that the deaths were due to the explosion of the arsenal laboratory, caused by the spontaneous combustion of red and white star fireworks left drying in the hot sun in heat-absorbing metallic pans. Upon explosion, a hot pellet entered the open window of the “choking” room and ignited the cartridges on the work table, causing the fire and explosion that led to the deaths and injuries of those working in the room.

The jury further ruled that Brown was guilty of carelessness and negligence in leaving highly combustible materials so close to a building where others were working. They found him guilty of showing a blatant disregard for human life and recommended a serious rebuke by the government. However, no criminal charges were recommended by the jury.

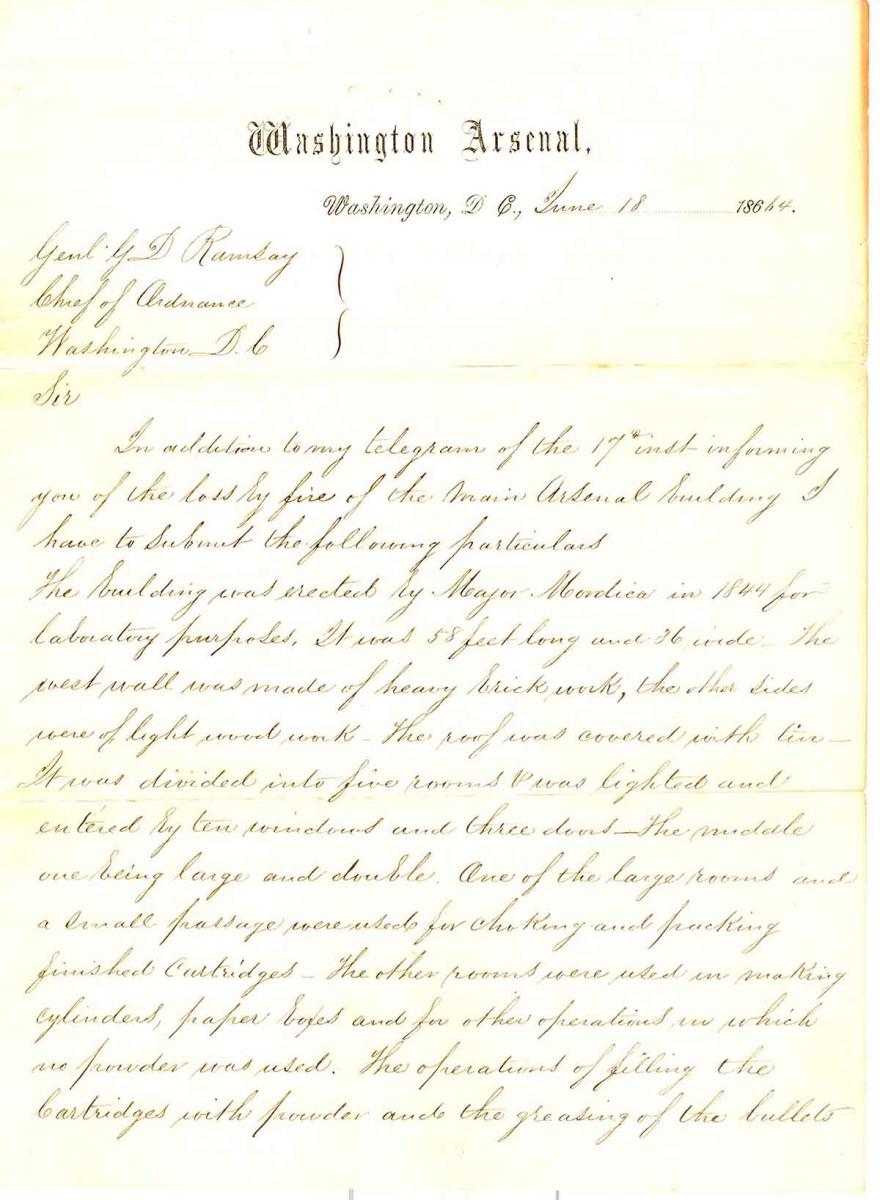

In his June 18 report to the Chief of Ordnance, Gen. George D. Ramsay, Major Benton first gave a short history of the arsenal building, writing that the structure was built in 1844 and was designed specifically for laboratory purposes. Its dimensions were 58 feet long and 36 feet wide, with heavy brick work on the west wall, lighter brick on the remaining walls, and a roof of tin. There were a total of 10 windows and three doors, the middle being a large double door. It was through these windows and doors that a large number of the female arsenal workers would make their escape.

He then described the various functions that took place in each of the five rooms, including the making of cylinders, paper boxes, and “other operations in which no powder was used.”

He made sure to point out that “great care was taken to distribute the different operations so as to lessen the loss of life should an explosion occur.” He further noted that “every precaution was taken to prevent explosion taking place by sweeping up loose powder, and carpeting the floors.”

Benton then suggested a cause for the explosion: “The accidental ignition of some stars which Mr. Brown the Master Laboratorian had prepared and laid out to dry in the sun, about 35 feet from the South end of the laboratory.” (Benton estimated that there were approximately 160 pounds of white stars and 15 pounds of red.)

The temperature outside the building had become severe enough as to cause the explosion of those stars containing sulphur, Benton wrote, sending streaming pellets through the open window of the “choking” room, leading to the deaths of the women working there.

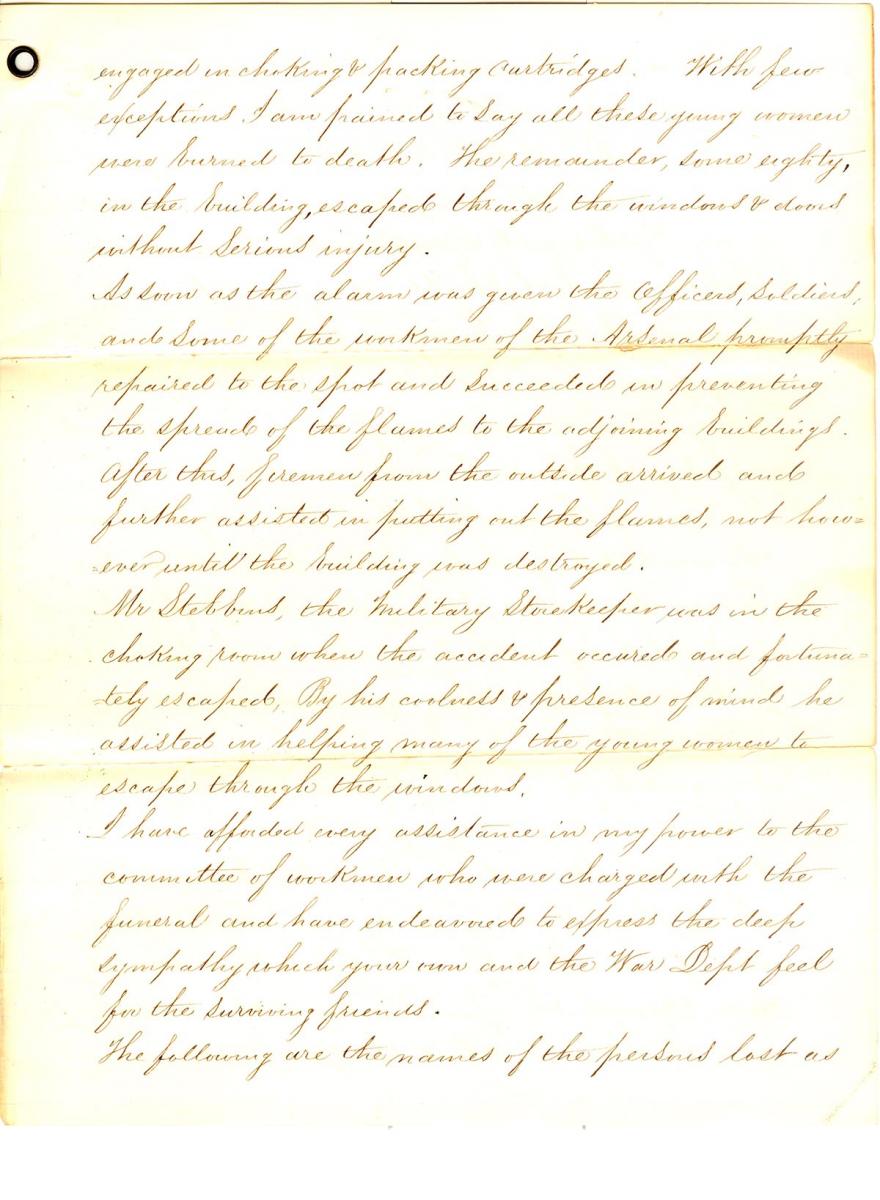

Some 80 others in the building, he wrote, were able to escape through the open windows and doors of the adjoining rooms. He estimated that there were anywhere from 50,000 to 75,000 finished and unfinished carbine cartridges in the building at the time.

After praising Stebbins for his efforts in evacuating those who had survived the explosion, as well as the firemen who “from the outside arrived and further assisted in putting out the flames, not however until the building was destroyed,” Benton then sought to exonerate himself.

“It may not be improper to state that while I am, as the commanding officer of the post, held responsible for its operations,” he wrote, “I am compelled by the variety and extent of these operations to rely much on the care and judgment of the Master workmen to prevent accidents.”

Brown had been in the laboratory business for 37 years, he stated, and it was in him whom he had placed his trust. Although Benton offered no serious condemnation of Brown, he also failed to provide him with even the mediocre defense he had given during the coroner’s inquest the previous day.

The Community Raises a Memorial to the Victims

Ironically, the June 18 issue of the Washington Star reported that on the day of the tragedy a letter was received at the arsenal thanking the employees for their contribution of $170 for the relief of the employees at the Alleghany Arsenal, which had experienced a similar explosion less than two years earlier.

The Star also mentioned that when the War Department was first notified of the explosion at the Washington Arsenal, they were also informed of a fire at the Watervliet Arsenal in New York that same day.

Two days later, the Star seriously vilified Brown and suggested he not be given another position where he could possibly contribute to another tragedy. Although they wished him no harm, they wrote, placing fireworks so close to a window where others were working showed a certain “degree of indifference to human life” on his part.

On June 20, the day after the funeral, a meeting of the arsenal employees was held to discuss ways in which funds could be raised to erect a monument in memory of their fallen co-workers. A circular was sent out to the community, resulting in the collection of $3,000 by the following year. Sculptor Lot Flannery of the Flannery Brothers Marble Manufacturers was commissioned to design and sculpt the memorial.

One year after the tragedy, a 25-foot-high-marble and granite statue was dedicated in Congressional Cemetery to honor those who had perished in the Washington Arsenal fire.

At the top of the shaft stands a young woman with clenched hands, looking downward as if grieving over the senseless loss of life below her. The granite base depicts the fire and explosion, showing smoke rising from the arsenal laboratory. On the shaft itself are the names of the 21 victims:

Postscript

Less than one year after the fire, the Washington Arsenal was again in the news when the conspirators charged with the assassination of Lincoln were imprisoned there. After being found guilty by a military court, Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt were hanged on the grounds of the arsenal on July 7, 1865. Four others received sentences ranging from six years to life at hard labor.

Jay Bellamy is a specialist with the Research Support Branch at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, where he has been employed since April 2000. He is a student of the Civil War, with special emphasis on the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as the life and times of Abraham Lincoln. In 2008, he published his first book, Dear Jennie, a mystery novel that centers on the Gettysburg battle.

Note on Sources

Major Benton’s report on the fire to the Chief of Ordnance is located in Miscellaneous Reports from and to the Chief of Ordnance Relating to Inspections, Arsenals, Investigations, and Claims, 1844–1902, Records of the Office of the Chief of Ordnance, Record Group 156, National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

Contemporary newspaper accounts of the tragedy were found at the Congressional Cemetery’s website.

Additional information was found in James Swanson’s Bloody Crimes: The Chase For Jefferson Davis and The Death Pageant For Lincoln’s Corpse (New York: William Morrow, 2010) and Brian Bergin, “Tragedy At City’s Arsenal,” May 17, 2008 (www.washingtontimes.com/news/2008/may/17/tragedy-at-citys-arsenal).