Attachments: Faces and Stories from America's Gates

Summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2

By Bruce I. Bustard

"I must have cried a bowl full of tears."

"I would also find it impossible to live in a country where all my family have been killed."

One came with plenty of money; another carried only a handful of belongings. One was a visitor; another was a citizen returning home. One had her papers in order; another brought false documents hoping to find a new life.

All of these men, women, and children left likenesses and traces of their journeys to America's entryways. Entering, leaving, or staying in America—their stories were captured in documents and photographs that were attached to government forms.

A new National Archives exhibition in Washington, DC, Attachments: Faces and Stories from America's Gates, draws from the millions of immigration case files in the Archives to tell a few of these stories from the 1880s through World War II. It also explores the attachment of immigrants to family and community and the attachment of government organizations to immigration laws that reflected certain beliefs about immigrants and citizenship. These are dramatic tales of joy and disappointment, opportunity and discrimination, deceit and honesty.

Attachments is organized into three sections: "Entering," "Leaving," and "Staying." As visitors enter the exhibition, they will walk by a large (8 feet by 26 feet) photomural of Angel Island, the main processing station on the West Coast, especially for Asian immigrants. They then pass through large gates embedded with photographs and documents from the exhibition. Each case will feature a large photograph of the individual whose story is told.

Entering

Entering America meant being able to join a spouse or parent; it meant a chance to marry, start a business, pursue an education, and bring family members to the United States. For U.S.-born Asian Americans returning to their birthplace, it was a test of their citizenship. For those escaping religious or political persecution, the outcome of their immigration application could mean life or death. The records in "Attachments" reveal that the answer to the question of who could pass through America's gates and be allowed to join our national community often depended on such factors as where a person was from, race and gender, and when and where the person tried to enter.

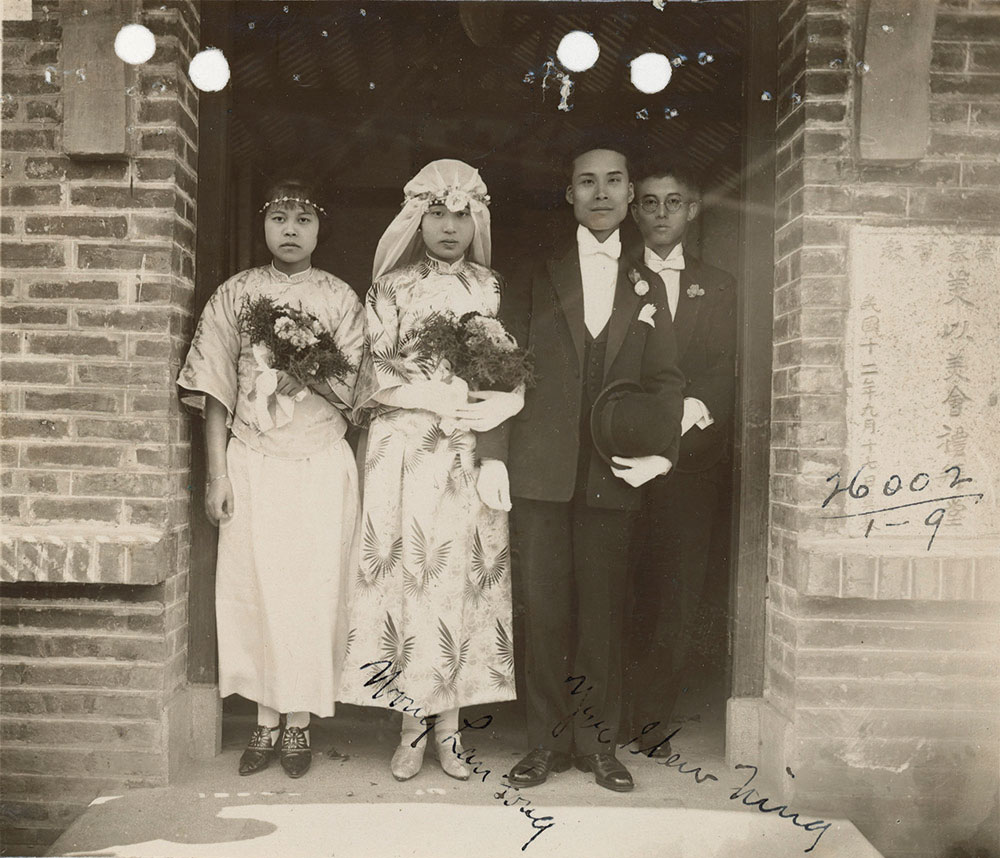

For example, when Chun Sik On arrived in San Francisco in 1883, he had to bring a certificate proving that he was a "trader" and therefore not covered by the general ban on Chinese entering the country under the recently passed Chinese Exclusion Act. In 1927, Wong Lan Fong and her new husband, Yee Shew Ning, fashioned strategies that permitted them to enter the United States despite the commonly held belief that most Asian women were trying to enter the United States for immoral purposes. Richard Arvay, a Jewish refugee from Austria, benefited from a brief relaxation in immigration regulations that allowed him to come to the United States during World War II. When faced with the possibility of having to go back to Austria after the war, he wrote, "I would also find it impossible to live in a country where all my family have been killed."

Leaving

Americans see their country as "a nation of immigrants"—a place to get a fresh start and a chance to make a new home. Millions who came here found freedom and opportunity, if not for themselves, then for their descendants. But others who came to America's gates could not enter, and some who entered later decided to return or were sent home. For some, leaving was part of their original plan—to make money on a temporary sojourn or to simply visit the United States. For others, tragedy, a criminal past, or injustice drove them away. Immigrants who wanted to enter but failed to qualify because of laws or regulations were cut off from their dreams. Even those who crossed America's threshold were subject to government control and deportation if, as aliens, they committed a crime, supported an unpopular political cause, or violated a regulation.

Mary Yee, a white woman born in Michigan, "became" Chinese in the eyes of the law when she married Yee Shing. As the couple prepared to leave the United States in 1922 to educate their children in China, they had to certify her right to return to the United States using a form designed for a "lawfully domiciled Chinese Laborer."

Lee Puey You, a Chinese woman, came to America in 1939 posing as the daughter of a man already admitted. She spent 20 months on Angel Island before being deported and remembered her time in detention bitterly, saying that she "must have cried a bowlful of tears," there.

Kim Ok Yun, a Korean nationalist, fled from the Japanese occupying her homeland. She spent a few years in college in the United States during the 1930s but then returned to Korea and resumed her political activities until she was arrested and probably executed.

Staying

Coming to America meant leaving behind the familiar. And while not all immigrants chose to stay, those who did faced both opportunities and challenges in making a life in a new land. Feelings of loss and nostalgia over what was left behind mixed with the thrill of greater freedom and the chance to begin anew. The safety and comfort of associating with compatriots from "the old country" competed with a desire to demonstrate loyalty to new communities and a new nation. American ideals of inclusion, democracy, and individual rights faced off against the reality of prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping.

Mary Louise Pashgian came to the United States fleeing persecution in Armenia. After Michael Pupa's parents were killed by the Nazis, he spent two years hiding in the Polish forests; he eventually came to the United States and was raised by a family in Cleveland, Ohio. Kaoro Shiibashi, who was born in Hawaii, was taken to Japan as a toddler. In the 1930s he decided, "I wanted to see my native land," and he returned to the United States. Despite his Hawaiian birth certificate, he was initially refused entry. Eventually admitted, he spent the rest of his life in the United States, including a stay at the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming during World War II.

All these details—the inspiring and uplifting as well as the mundane and heartbreaking—are recorded in the documents presented in "Attachments." The documents themselves represent a kind of a gateway—a gateway to America's immigrant past and a gateway to understanding its complexity.

Bruce I. Bustard is senior curator in the Center for the National Archives Experience at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. He is the curator of Attachments: Faces and Stories from America's Gates, and the son of an immigrant from Scotland.