'P.S.: You Had Better Remove the Records'

Early Federal Archives and the Burning of Washington during the War of 1812

Summer 2014, Vol. 46, No. 2

By Jessie Kratz

When British troops began to advance toward the United States’ new capital of Washington in the summer of 1814, it was clear that government leaders had not prepared an adequate defense for the city and its government buildings.

The British navy already had control of nearby Chesapeake Bay and some 4,500 troops in the port town of Benedict, Maryland—poised for an attack on the capital.

Despite the show of force, the secretary of war, John Armstrong, was convinced the British were more interested in the port of Baltimore than in Washington, which then had only 8,200 residents.

Secretary of State James Monroe felt differently and met with President James Madison to discuss the enemy’s intentions. Then Monroe himself rode by horse, accompanied by cavalry, into southern Maryland to scout the situation.

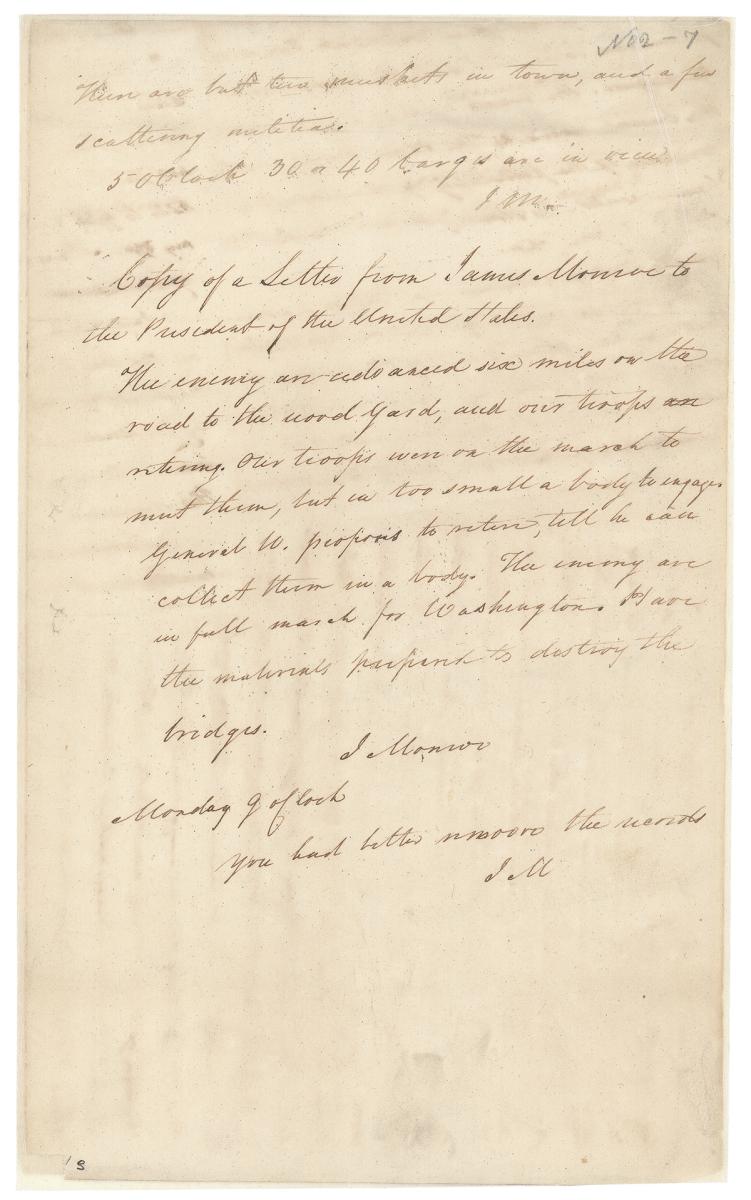

Upon seeing the British advancing toward Washington, Monroe dispatched a note to President Madison. It said that the British were pushing toward the capital, American troops were retreating—and they were outnumbered.

“The enemy are in full march for Washington. Have the materials prepared to destroy the bridges,” Monroe wrote. And in a significant postscript, he added: “You had better remove the records.”

Monroe’s message set off a scramble among government officials to round up all the records they could. The British surely would burn them if they reached the capital.

And so clerks packed such things as the books and papers of the State Department; unpublished secret journals of Congress; George Washington’s commission and correspondence; the Articles of Confederation; papers of the Continental Congress; and all the treaties, laws, and correspondence dating back to 1789.

Along with these early records, the clerks also bagged up the Charters of Freedom—the collective term for the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights And so these three documents began a long journey as the War of 1812 raged.

The journey would not end until 1952, when all three were placed together, side by side, in special encasements in the Rotunda of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.

Early Federal Papers Faced Many Moves, Poor Storage

Each year, millions of people visit the National Archives Building to view the Charters of Freedom in the Rotunda. Within the Archives’ vaults and stacks, millions of other federal records are safely stored, ensuring they will be available to researchers for years to come.

This was not always the case.

Between the First Continental Congress in 1774 and the establishment of the National Archives in 1934, the government’s records lacked a stable and secure storage environment. Early in the nation’s history, federal records faced a number of potential calamities, including poor storage conditions, neglect, theft, and fire.

Perhaps the most striking example of the perilous conditions the Charters faced occurred two centuries ago during the War of 1812. The first Congress under the Constitution gave the responsibility to preserve records of the government to the new Department of State.

These early records included the papers of the old Department of Foreign Affairs; the papers of the Confederation and Continental Congresses; George Washington’s papers as Commander of the Continental Army; and the Declaration of Independence and Constitution.

The First Congress also charged the Department of State with gathering and preserving many of the important records the new federal government would create. At the same time, it left each federal department or court responsible for keeping its own archives. In doing so, Congress failed to create a consistent record-keeping policy or a central, safe place for storing the new government’s records.

The Residence Act of 1790 created a new home for the federal government, in a yet-to-be-built city along the Potomac River on land donated by Maryland and Virginia. The act, however, scheduled the move to the new capital for 10 years later, in 1800, and forced federal clerks to pack official papers and move them from New York—the prior seat of gov- ernment—to Philadelphia, the interim seat of government, then later to Washington.

The New Capital, Washington: No Better Place for Records

While in Philadelphia, the State Department moved to several locations around the city, as well as outside of the city to avoid recur- ring yellow fever epidemics. For each move out of Philadelphia, the department packed up furniture, books, and papers—including, most likely, the Declaration, Constitution, and the Bill of Rights (newly passed in 1791)—shipped them up the Delaware River, and carted them to Trenton, New Jersey.

When the department moved back to Philadelphia, clerks took the reverse trip. They repeated this process three times, each time putting the nation’s most precious historical records in jeopardy.

In May 1800, federal department heads began moving their offices and staffs to the new federal city: Washington. The government loaded its books and papers, including the archives and the Charters of Freedom, onto ships and transported them south to Washington. Unfortunately, the move did not immediately improve the safety and security of federal records.

Early transplants to Washington faced conditions unlike those in Philadelphia or New York City. Architect Pierre L’Enfant created a very ambitious plan for the new city, but by the time the government began moving in, his plan was not even close to being realized.

In 1800 Washington bore little resemblance to a city, let alone the majestic seat of empire L’Enfant had envisioned. Many planned buildings remained under construction or altogether unbuilt. The city was barely equipped to house anyone, let alone the federal government and its archives.

Newly arriving government officials expressed their disappointment with the lack of amenities the new city offered.

One member of Congress described his surroundings as “both melancholy and ludicrous . . . a city in ruins.” Another Representative compared L’Enfant’s plan with what he actually saw:

The Pennsylvania Avenue, leading, as laid down on paper, from the Capitol to the President’s Mansion, was then nearly the whole distance a deep morass, covered with alder bushes, which were cut through the width of the intended avenue during the then ensuing winter.

By June 7, 1800, the Department of State and its archives, including the Charters, lacked a dedicated space. For the first few months, State and several other government offices shared the Treasury Department Building, east of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW.

Luckily, the State Department’s move turned out to be very well timed. In January 1801 a fire destroyed a portion of the Treasury Depart-ment’s records, including both current documents and historical records. Had State not moved out of Treasury’s building, the nation’s most important early records, including the Charters, likely would have burned.

Packing, Unpacking, Packing Again Around Washington

A few months later, the State Department briefly moved into a house on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue between 21st and 22nd Streets, NW. The following summer, they packed up their archives and the Charters and moved yet again—this time into a new building west of the Executive Mansion, on the site where the Old Executive Office Building now sits at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue, NW,

and 17th Street, NW. Again, the Department of State shared space with other government offices, including the Department of War and the Department of the Navy.

Though the numerous relocations did not require traveling great distances, conditions in Washington made any move difficult. In dry weather the dirt streets turned to dust bowls; in the rain the roads became rivers of mud.

Getting around Washington on foot or even carriage often became a nightmare—the city had few discernible roads, no street signs, and only a handful of buildings to serve as landmarks. These were not ideal, or even suitable, conditions for transporting and safekeeping the nation’s most valuable documents.

With each move within the city, the archives faced the same problems as they had before arriving in Washington—the records had to be packed up and moved, then unpacked and stored again.

Government officials of the era knew that the nation’s most precious documents endured inadequate storage conditions. In 1810, Congress investigated the condition of federal archives housed in public buildings.

During the investigation, Secretary of State Robert Smith reported on the “ancient records and papers” in his custody. He described how the records, which he deemed “highly important to the History of the United States,” were housed in trunks and boxes in the cramped attics in their building.

Smith acknowledged his department’s inability to properly store the papers and pleaded with Congress to build a fireproof building, remove the papers from his custody, and “to employ a person to arrange the papers in proper order.”

After all departments reported on the condition of their archives, the committee acknowledged the records were in “a state of great disorder and exposure; and in a situation nei- ther safe nor convenient nor honorable to the nation.” They further concluded records had been exposed to fire and robbery, dangers augmented by the lack of security and fireproofing.

Ultimately, rather than moving each department’s archives to a safe, central place, later that year Congress appropriated funds to construct “as many fire proof rooms as shall be sufficient for the convenient deposit of all the public records of the United States belonging to, or in the custody of the State, War, and Navy Departments.”

War of 1812 Poses New Threat to Records: Enemy Capture

With the onset of the War of 1812, the nation’s early records faced yet another threat: destruction by invading forces. At the time the war began, government officials had done little more to safeguard the nation’s records and had not yet built the congressionally approved fireproof rooms.

In general, Washington, with a population of 8,200, remained very much a city in progress. The city still offered little in terms of infrastructure, culture, or commerce. Many government officials expressed a desire to move the capital once again, and these complaints came before the city faced a major setback late in the war.

In 1813, the British navy, in control of the Chesapeake Bay, destroyed American warships, burned government supplies, raided port towns, and halted coastal trade.

By the summer of 1814, with 4,500 British troops roughly 40 miles away in Benedict, Maryland, government officials began to take the threat seriously.

In August, Monroe himself visited the front lines, joining Gen. William Winder, whom Madison had recently appointed as commander of the defenses of Washington and Baltimore.

Once Monroe saw where the British were headed, he sent his warning to Madison and said the outnumbered American troops were retreating. Monroe’s message sent the citizens of Washington into a frenzy. Local residents fled, taking with them the city’s supply of horses, wagons, and carts.

Government agents trying to save as many federal records as possible scrambled to secure any remaining means of transport they could find. Some government clerks even tried using their official positions to impound carts and wagons, but they had little success in persuading residents who were busy removing their personal belongings.

Upon hearing of Monroe’s message, State Department clerks John Graham, Stephen Pleasonton, and Josias King took it upon themselves to save the valuable archives—including the Charters of Freedom—stored at State. They bought coarse linen to make bags into which they stuffed the archives and loaded them into carts.

Recollections Years Later Help Tell Story of Records

Few contemporary accounts of the Charters’ evacuation from Washington exist, and most of what is known about the events comes to us from recollections recorded years later.

Pleasonton recalled, in an account taken 34 years later, that while he transported the documents through a passageway, he ran into Secretary of War Armstrong, who made a point to inform Pleasonton that he was being foolish because the British were not coming to Washington, so there was no reason for alarm.

“I replied that we were under a different belief,” Pleasonton recalled. “It was part of prudence to preserve the valuable papers of the Revolutionary Government.”

An 1883 Washington Post article further dramatized the evacuation by reporting “just as [Pleasanton] was about to leave, and with the sound of the British artillery upon capitol hill upon his ears, he passed through the room of Secretary Monroe and saw there the Declaration of Independence and General Washington’s first Commission, in frames. Knowing that these would be very valuable acquisitions to the British Museum, he broke the glass, removed them from their frame, rolled them up and mounting his horse, rode off.”

It’s a good story, but it is clearly embellished given that the British had not yet arrived in Washington when the clerks were clearing out the records. That said, the basic fact that the clerks managed to gather and carry the nation’s most valuable records out of Washington—saving them from possible destruction—remains true.

The clerks first took several document-loaded carts to a vacant gristmill on the Virginia side of the Potomac River, a few miles above Georgetown. The mill, however, sat near a foundry that made munitions for the war. Although the foundry was on the Maryland side of the Potomac, the clerks still feared it might bring the enemy too near their precious cargo.

Pleasonton recounted that he considered “the papers unsafe at the Mill, as, if the British forces got to Washington, they would probably detach a force for the purpose of destroying a foundry for canon and shot in its neighbor- hood, and would be led by some evil disposed person to destroy the Mill and papers.”

They looked for another location.

The next day, August 24, 1814, the clerks obtained wagons from nearby farmers and moved the documents to Leesburg, Virginia, about 35 miles northwest of Washington. There, they locked the valuable documents into a cellar vault of an abandoned house and gave the keys to Leesburg’s sheriff for safekeeping.

Congress's papers, lacking anyone with such prudence, were in greater jeopardy. Congressional records had not been transferred to the Department of State and were still held in the Capitol. By the time the young clerks of the House and Senate offices took action, it was too late to rescue all of the records.

After finally obtaining a cart and oxen, House clerks Samuel Burch and J. T. Frost frantically moved House papers to a secret location in the country nine miles outside of the city. Senate clerk Lewis Machen took a wagonload of documents to his farm in Maryland’s Prince George’s County, which adjoins the District of Columbia. The following morning, his colleague, John McDonald, shepherded the documents to the town of Brookeville, Maryland, in northern Montgomery County.

In the chaos, the House and Senate clerks knew they had to leave valuable materials behind. Machen noted that he loaded what he considered the most valuable documents, including confidential papers, “one of which I knew to contain the number and positions of the entire American military force,” and he believed the documents he loaded in the wagon constituted the only copy of the Senate’s history over the past quarter century.

Burch and Frost also salvaged as many of the House’s most important papers as they could, but in a letter to Congress they expressed their frustration that more could have been saved: “Everything belonging to the office might have been removed in time, if carriages could have been procured; but it was altogether impossible to procure them, either for hire, or by force.”

British Invade, Destroy Capitol, White House, Other Buildings

While government clerks evacuated Washington, the British marched, unimpeded, into the city. They found Washington nearly abandoned. Congress had recessed for the summer, and President Madison, after a brief appearance at the front lines, had retreated to Virginia. Most other residents had fled to the countryside.

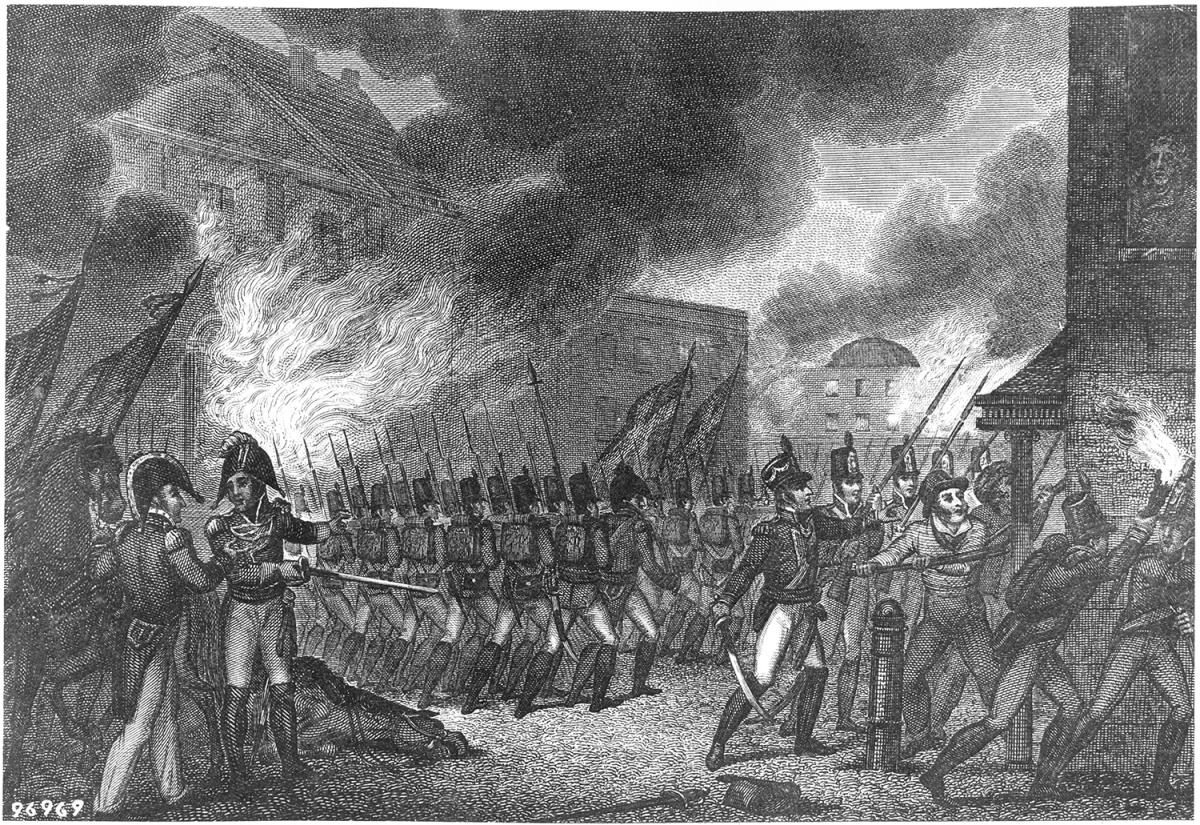

In the vacant city, British troops vandalized and set fire to the unfinished Capitol building—which consisted of just the North (Senate) and South (House) wings—the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court. They then marched up Pennsylvania Avenue and burned and looted the Executive Mansion and the nearby government buildings. At the Navy Yard, they torched ships and ammunitions.

The next morning the city was still smoldering—both with fire and 100-degree temperatures. The British had largely spared private property, but a fierce storm had uprooted trees, leveled buildings, and flattened homes. Once the storm subsided, British forces retreated, satisfied the city was sufficiently devastated.

State Department historians credit Monroe, Pleasonton, and their colleagues for saving the nation’s irreplaceable archives.

“Imagine,” State Department Historian Gaillard Hunt wrote in 1914, “the indelible shame which would have followed if they had been less loyal and resourceful, and Cockburn and Ross [the British commanders] had carried away with them, as trophies of their exploit, the rolls of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.”

President Madison returned to a city in ruins. He lambasted the British forces for wantonly destroying “depositories of the public archives, not only precious to the nation as the memorials of its origin and its early transactions, but interesting to all nations as contributions to the general stock of historical instruction and political science.”

In addition to the loss of many congressional records, archives of the Navy, War, and Treasury Departments went up with the flames that destroyed their buildings.

However, the government had to carry on.

Madison occupied a house formerly occupied by the French minister and never again lived in the White House, staying in private residences for the rest of his term. Congress met in Blodgett’s Hotel, one of the few public buildings to survive the British attack.

After spending a few weeks in Leesburg, State Department officials quietly returned the papers and archives, including the Charters, to Washington. The archives moved into a house on G Street, the Department of State’s temporary office.

In addition to the extensive physical damage, the attack struck a great psychological blow to the still-growing city. Congress appropriated funds to repair and rebuild the Executive Mansion, the Capitol, and public offices on their present sites rather than start from scratch. To protect their real estate investments, private citizens and businessmen also raised money to temporarily house the government and reconstruct government offices

Charters Move Around, Receive Little Special Care

Although the British occupation nearly destroyed the Charters of Freedom—and actually destroyed many valuable federal records—Congress did not include provisions for a centralized archives in its plans to rebuild the city.

Over the years, the Charters and other valuable historic documents continued to endure poor storage conditions, lack of suitable space, constant shuffling around the city, and a near-constant threat of fire.

Until 1841, the Department of State and its archives (including the Charters) moved to various locations around Washington. In that year, Secretary of State Daniel Webster transferred some the most valuable historical documents to the commissioner of patents, who had just moved into a fireproof building—the new U.S. Patent Office. This same building now holds the Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery.

The Patent Office displayed the Declaration in a sunlit room for many years. Both the light and smoke from a nearby fireplace caused much of the damage and fading that today’s visitors see.

The Declaration briefly moved to Philadelphia in 1876 for exhibit at the Centennial International Exhibition, and when it returned, the State Department hung it in its library until 1894. That year, State Department officials finally recognized its fragile and deteriorated condition and stowed it away in a steel safe. The two other charter documents—the Constitution and the Bill of Rights—had remained out of public display and therefore escaped similar deterioration.

In 1920, a committee appointed by the secretary of state reported that the department lacked sufficient space, security, or fireproofing to safely store the archives. It recommended that some historical documents, including the Declaration and the Constitution be transferred to the Library of Congress.

The following year, the Librarian of Congress happily took over guardianship of the documents and in 1924 placed the Constitution and Declaration of Independence on public display.

Ten years later, Congress created the National Archives to house the federal government’s permanently valuable records. The Archives immediately began identifying and locating federal records in storage in various locations in Washington and around the country.

Staff found records in basements, attics, carriage houses, and abandoned buildings. The records had suffered from neglect, vermin, and theft as a result of being housed in unsuitable and unsupervised storage areas.

Even some of the nation’s most important documents such as the Bill of Rights were stored in potentially hazardous conditions. The Bill of Rights was not transferred to the Library of Congress with the Declaration and Constitution; it remained with the Department of State in the Old Executive Office Building.

A 1936 Washington Post article reported that the Bill of Rights was kept in a “khaki-bound cardboard folder sitting upward with other early papers . . . in an uninspiring green steel cabinet. . . . It would take no expert cracksman to open the cabinet. It could almost be done with a can–opener. Most of the time it is left unguarded.”

In 1938 the Department of State transferred the Bill of Rights and the bulk of the historical records in its custody to the National Archives.

The newly appointed Archivist of the United States, R.D.W. Connor, believed that America’s other founding documents, including the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and papers of the Confederation Congresses, would also be sent to the new National Archives. In fact, the building’s 75-foot-high rotunda was designed specifically to display the Declaration and the Constitution.

Even so, for many years the Librarian of Congress refused to relinquish the documents.

No Permanent Home for Charters Until 1952 at the National Archives

More than a century after the War of 1812, while World War II swept through Europe, the Librarian of Congress made plans to evacuate the priceless documents out of Washington as a precautionary measure. He ordered the Declaration and the Constitution, along with other historically valuable records, sent to the United States Bullion Depository, better known as Fort Knox, Kentucky. The documents remained there for most of the war. (The Declaration was brought back to Washington for a week in 1943 and displayed during the bicentennial of Thomas Jefferson’s birth.)

By the 1950s, the Archives had lost patience with its empty shrine to the founding documents.

President Harry Truman’s remarks during a Constitution Day ceremony at the Library of Congress opened the door for the Archives to makes its move: “I hope that these first 10 amendments will be . . . sealed up and placed alongside the original document.”

Archivist Wayne Grover entered secret negotiations with the Librarian of Congress to acquire the Declaration, the Constitution, and papers of the Continental and Confederation Congresses.

In 1952, with great fanfare, the Librarian of Congress agreed to transfer these records to the National Archives. When the Constitution and Declaration arrived on December 13, they joined the Bill of Rights for permanent display in the National Archives Exhibition Hall.

During the dedication ceremony, President Truman observed: “The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are now assembled in one place for display and safekeeping. Here, so far as is humanly possible, they will be protected from disaster and from the ravages of time.”

During the renovation of the National Archives Building between 2001 and 2003, the Charters of Freedom underwent conservation treatment and were sealed in new state-of-the-art encasements.

With the exception of the 2001–2003 period, the three documents have been on continuous display in the Rotunda as a highlight for millions of tourists, school children, and other visitors each year. While some visitors comment on their faded text, it is perhaps more appropriate to marvel at how they have survived their long journey to the Archives.

Jessie Kratz is the Historian of the National Archives.

Note on Sources

Primary sources consulted include: Records of the Department of State (Record Group 59), Records of the National Archives (RG 64), Records of the U.S. House of Representatives (RG 233), American State Papers, United States Congressional Serial Set, U.S. Statues at Large, Annals of Congress, Washing-ton National Intelligencer, Washington Evening Star, Washington Post, The American Presidency Project, and Founders Online (www.founders.archives.gov).

For a summary of the burning of Washington, see Anthony Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (Naval Institute Press, 1998). For the early history of the Department of State see Gaillard Hunt, The Department of State (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1914), and The Buildings of the Department of State (Department of State Publication 89, Department and Foreign Service Series: 158, 1977).

For the early history of Washington, D.C., see James Sterling Young, The Washington Community, 1800–1828 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966); Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington: Village and Capital, 1800–1878 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962); Washington, City and Capital, by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1937); and Centennial History of the City of Washington, DC (Dayton, OH: United Brethren Publishing House, 1892).

Sources relating to the travels of the Charters of Freedom include The Constitution of the United States Together with an Account of Its Travels Since September 17, 1787, by David W. Mearns and Verner W. Clapp (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950), and Declaration of Independence: The Adventure of a Document (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 1976).