Authors on the Record: Custer's Trials

Winter 2015, Vol. 47, No. 4

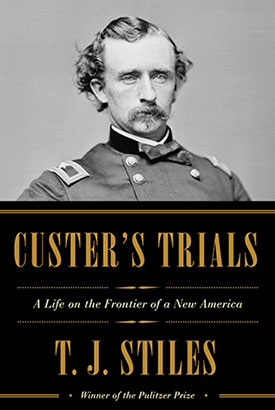

Custer's Trials

A Life on the Frontier of America

An interview with T. J. Stiles by Keith Donohue

Custer's Trials: A Life on the Frontier of America is the new biography of Gen. George Armstrong Custer and his turbulent times. Digging into the archives, T. J. Stiles gives us a new portrait of Custer. From his trials as a cadet at West Point to his battlefield successes during the Civil War, Custer's rise was mercurial, but the life that followed was a struggle to accommodate his passion and ambitions with the political landscape of the military and society at large. Custer's Trials is a fascinating account of the man and his times.

T. J. Stiles is the author of The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt, winner of the 2009 National Book Award in nonfiction and the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in biography, and of Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. He is a member of the Society of American Historians and a former Guggenheim fellow.

In the preface, you call Custer an "exaggerated American" and a man out of time. Talk a bit about what makes Custer such an elusive, yet iconic, figure.

Ironically, what makes it so hard to understand Custer is that we think we know him already. His spectacular defeat and death at the Little Bighorn seared him into national memory. Many Americans revile him because of his role as an Indian fighter, and because his flamboyance makes him seem like the embodiment of arrogance. But Custer also has fans. Many have attempted to restore his reputation, mostly through books about his successful career in the Civil War.

This polarized view of him as villain or hero—as frontier soldier or Civil War general—creates a trap for the biographer. What I found made my picture of Custer's personality and public roles richer, more complicated, rather than better or worse. I found that a more comprehensive portrait of his life possessed fresh drama and shed new and often troubling light on the making of the modern United States.

Custer's Trials is structured around trials, both literal and figurative, personal and professional. What caused you to focus on the courts-martial as a way to build the story?

I wanted to draw on the inherent drama of courtroom proceedings. His courts-martial and the Reno Court of Inquiry marked the great departures in his life: the start of the Civil War and his military career, his transition to the frontier, and the climactic end of his life. But I also wanted to play on the inherent tendency Americans now have to prosecute or (less often) defend Custer. We often judge him guilty—but guilty of what? Being the face of often-brutal national policies toward Native Americans? Of his own personality flaws? Or both?

In these trials the formal institution of the U.S. Army confronted Custer's personality—his impulsive, self-indulgent side, which pitted him so often against military rules and culture. One theme in the book is how the Army pioneered the organizational society in America, how it introduced professionalization and systemization. Custer was the opposite of the organizational man, which led directly to his two courts-martial.

What did you discover about Custer's political maneuverings through the papers of Andrew Johnson and Ulysses Grant, both projects supported by grants from the NHPRC?

Custer threw himself into politics—both the little politics of personal connections and career maneuvering, and partisan politics. And a key player in both kinds was his fascinating wife, Libbie. During the Civil War, he worried about having his appointment to the rank of general confirmed by Congress, since he was a conservative Democrat and protégé of Maj. Gen. George McClellan, who was reviled by Radical Republicans. Custer frantically lined up Republican sponsors, and his wife lobbied senators who were charmed by her beauty and poise.

In 1866, Custer's partisan politics was the wedge that began to split an admiring public into fans and detractors. It helped to define his place in the post–Civil War Regular Army and fostered lasting tension with Ulysses S. Grant, which would explode in 1876, just before the Little Bighorn campaign. Grant's records show that he planned on putting Custer in charge of the black Ninth Cavalry Regiment. Custer went over Grant's head and wrote to President Andrew Johnson to ask to serve with white troops only. As it happened, Johnson was launching an explicitly racist appeal to reject the proposed 14th Amendment, along with any civil rights for freed slaves. He recruited Custer to go on his speaking tour, the Swing Around the Circle. Custer served as a delegate to the political convention of Johnson supporters and organized another convention of soldiers and sailors who backed the President. When Republicans swept the election, Custer retreated from politics and reported to his new post on the Great Plains.

But the Democrats recaptured the House of Representatives in 1875, reviving Custer's partisanship. He testified before a House committee in 1876, supporting allegations of corruption in the Grant administration, and socialized in public with Democratic congressional leaders—even though he was a serving Army officer. Grant was angry, and he had valid grounds to pull Custer from command of a column marching against the Sioux. It would have saved Custer's life. But Grant relented when Gen. Alfred Terry, Custer's immediate superior, appealed to him—and after Custer apologized, in terms that echoed his appeal for leniency in his first court-martial, 15 years earlier at West Point.

Custer's politics created other problems for him as well. In Texas in 1865, he sided with white planters in their attempts to control freed slaves. In Kentucky in 1872–1873, he commanded troops that took part in a federal offensive against the Ku Klux Klan in the state, but Custer criticized the duty in an official report. This was despite the fact that he developed profound respect for Eliza Brown, a remarkable young black woman who worked as his cook and domestic manager for six years. She tried to educate him on the wrongs inflicted on African Americans—in the end, to no avail.

How did the records at the National Archives help tell the story?

National Archives records were the foundation of much that is new and fresh in Custer's Trials.

Custer as the Anti-Organization Man: Correspondence up and down the chain of command, both in the Civil War and in the West, show how much of Custer's life was occupied by daily routines, logistics, training, and other mundane matters that create context for famous and dramatic moments. But they also show that Custer created a great deal of friction with superiors and built a reputation as a problem officer. For example, the files of the Adjutant General's Office show that Custer's transfer to the Dakota Territory in 1873 led to a major controversy mainly because Custer faced deep-seated skepticism, even hostility, at departmental headquarters in St. Paul.

Custer and Emancipation: In occupying Texas in 1865, Custer faced the consequences of emancipation. With Eliza Brown coaching him, he showed signs of real sympathy with former slaves. But he turned his back. In the records of the Freedmen's Bureau in Texas, I found a case I'd never heard of before: In October 1865, a black child who was being held illegally in slavery set out to find her mother. The white teenage son of the plantation owners found her, tore her away from her mother, tied her up, and dragged her behind his horse until she died in agony. Custer ordered the boy arrested. On reconsideration, he ordered him to be turned over the civil authorities, who were the same as held power during the Confederacy. They let the boy go. This is despite letters from Provisional Governor Andrew J. Hamilton, pleading with the Army to punish those who were murdering African Americans with impunity, because there was essentially no civil government in Texas.

Voices of Native Leaders: Though many of the negotiations between Army officers and American Indian leaders have been published in the Congressional Serial Set, I scrolled through countless microfilm rolls to read the handwritten transcripts of these talks. Migration through the high plains degraded vital resources for the nomadic peoples, and the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lakota, and other native leaders tried to explain their dilemma again and again. "Just let our people move through," the generals essentially said, again and again, never grasping the significance of the response: "But you're cutting down the timber, killing the game, overgrazing, and rendering the high plains uninhabitable."

The book ends with a wonderful line about Custer being "misremembered as needed by each new generation." How does he fit in an age of irony? How has our generation revised the story?

One way or another, Custer was America—and still is. In his accomplishments, his failings, his struggles with the way the world was changing, he embodied the best and worst in American values and culture. His outsized presence, his flair for publicity, and his tendency to create controversy have made him a decisive figure since almost the moment the Civil War ended.

In Custer's outlook, and in the contemporary adoration of him, we see Americans' reluctance to "cultivate a taste for distasteful truths," as Ambrose Bierce implored, to "endeavor to see things as they are, not as they ought to be." Our generation is no more honest if we dismiss Custer as a villain who got what was coming to him. I see biography as a branch of literature, which takes us to the uncomfortable place where we sympathize with individuals yet do not take our eyes off what human beings can do and be. Custer was a volatile, emotional man who still surprises us, in part because we are always reconsidering who we are as Americans.