Women Workers in Wartime

Personnel Records Offer Valuable Insight into Civilian Employees’ Lives

Fall 2016, Vol. 48, No. 3 | Genealogy Notes

By Cara Moore

Known suffragette Lucile Atcherson was the first woman to apply and test for employment with the U.S. Foreign Service. She had an impressive résumé, but her years of volunteering overseas as a medical aid provider during World War I, successful passing of the entry examination, and a nomination to the position by President Warren G. Harding in 1920 were just not enough to earn selection to the male-dominated position of diplomatic officer.

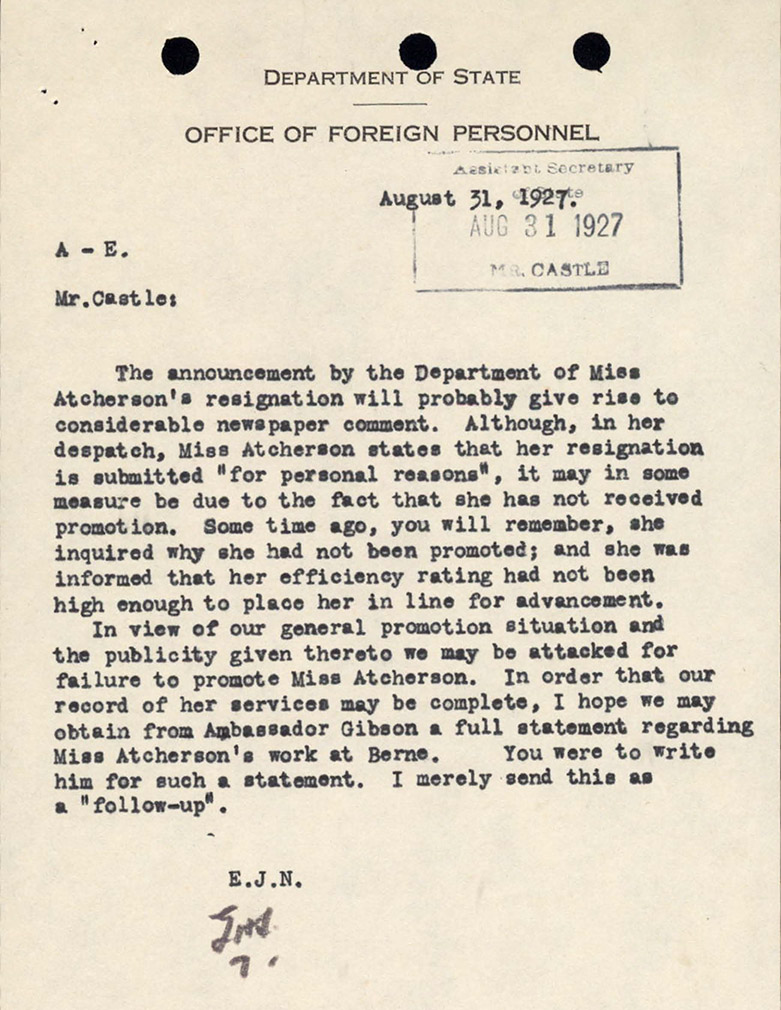

Even after Atcherson was appointed as a diplomatic officer, her tenure was not without its issues. Her Wikipedia article ends approximately here, noting that she had complained of nonpromotion and ultimately resigned from the position in 1927 because she was marrying and was not entirely happy in her assignment location of Panama.1

Where many online sources offer this “Cliff’s Notes” version of Atcherson’s life and employment, her official personnel folder holds a much deeper and more complete picture of the life and work history of this pioneer. For example, Atcherson’s federal employment began on December 4, 1922. Her personnel file contains details about the training she received and her appointments to several foreign offices throughout her career. She operated as a Foreign Service Officer for several years and received average efficiency ratings. She did, indeed, complain that she had not been promoted, and that letter can actually be found in her personnel folder. The complaint was succinct and detailed her work, noting that she never received a poor/unsatisfactory efficiency rating as well as the fact that all of the men hired when she was had been long since promoted.

Her personnel folder lists all of her successful efforts in overseas relations during World War I, and her application lists her many known languages and schooling, her date of birth, and both parents’ names, including her mother’s maiden name. Her file also includes an announcement of engagement to George Curtis, but her official resignation was denoted as “personal reasons,” certainly open to interpretation given what we now know.

Atcherson’s official personnel folder provides a prime example of a more complete genealogical resource than even an obituary or a short article may offer. Atcherson has certainly been documented beyond a Wikipedia article, but that cannot be said for many thousands of other women employed by the federal government. These women worked in positions usually reserved for men as well as those that were thought more acceptable for women at the time—such as nurses, secretaries, or more war-specific roles such as a friendly American female voice in overseas radio. The official personnel folders can offer broader insight into the lives of federally employed women during wartime.

The National Archives in St. Louis, Missouri, houses these archival official personnel folders (OPF) among other records. For a record to be considered archival, the individual’s employment had to end before 1952.

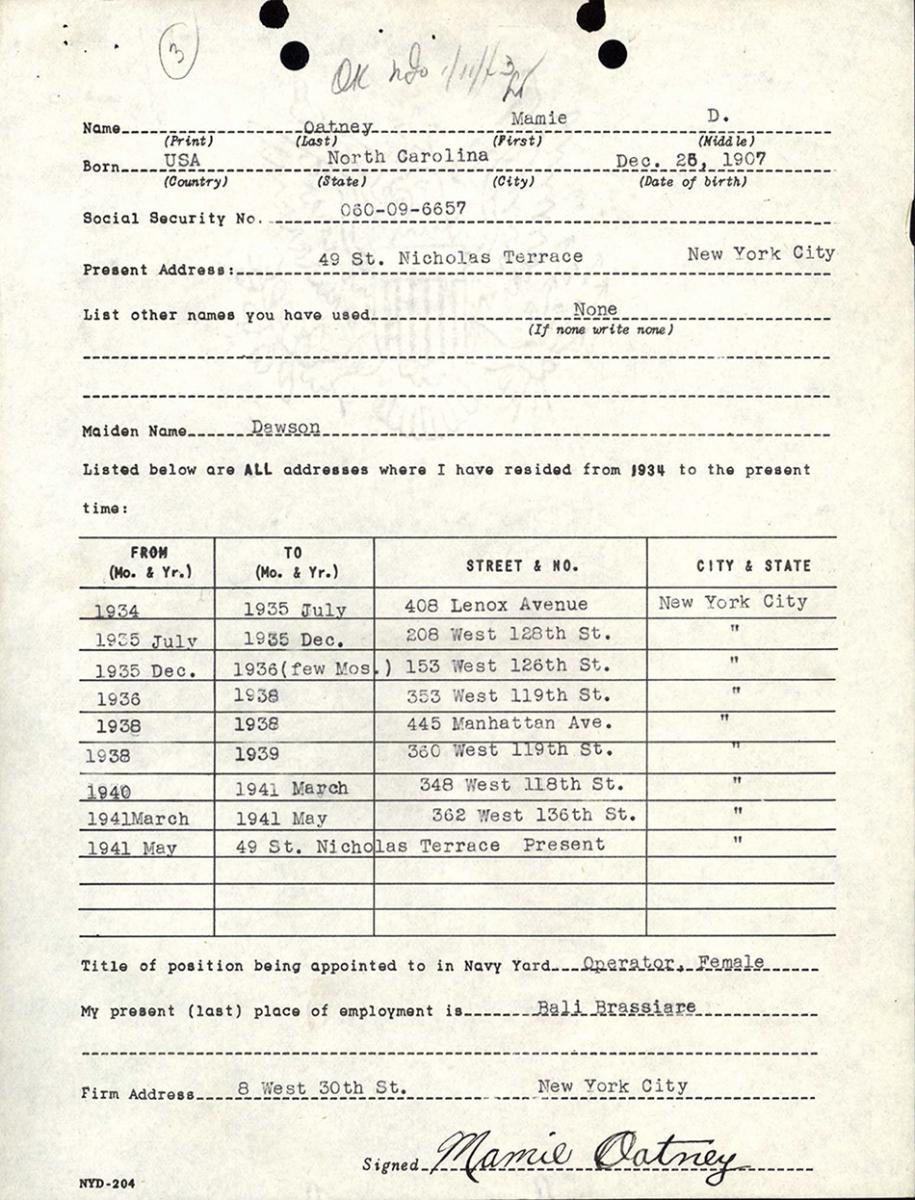

These records, which are open to the public, pertain to the specific individuals who served in a military or civilian capacity for the federal government rather than documentation of federal projects or cases.2 These records are rich with genealogical information such as names, addresses, birth dates, birth places, marriages (if applicable), next of kin, citizenship or naturalization, home addresses, and further biographic information. The folders document the employees’ entire employment histories, from start dates, including previous employment histories, through efficiency ratings, promotions, or trainings, to resignations and the reasons for separation. OPFs may also contain medical notes of any hardships that occurred during employment. And, as was the case with the Atcherson files, access to such files can provide a unique perspective or detailed insight into the wartime lives of federally employed women.3

In general, women’s genealogical histories can be especially hard to track because of their change in name at marriage. Socioeconomic factors such as male-dominated workforces also typically hinder genealogical research of women. Wartime civilian employment records present opportunities for genealogists to discover women’s histories during a time when society encouraged women to serve their country by working on the home front.

When the United States government entered a war, it offered work opportunities to women in significantly higher numbers than had been seen previously.4 The resulting personnel files from this surge in women’s employment within the wartime federal government may help researchers over some of the hurdles of researching female lineages. The Department of the Army Air Force, the Department of the Navy—formerly the War Department and split into individual agencies in 1939—and the Department of State have been the largest federal employers over the course of our nation’s history.5 All departments experienced a jump in employment during World War I and again during World War II.

Various sub-agencies under these three umbrella agencies executed many projects during wartime. For example, the Department of the Navy worked as the Military Sea Transportation Service in navy yards and navy hospitals; the Department of the Army Air Force employed a large number in the Army Transport Service and Labor Service Company; the Department of State hired for the Office of Facts and Figures, the Office of War Information, and Inter-American Affairs and Transportation. The hired personnel included women and also frequently included alien citizens who were not naturalized. These employees did important work for the country either in the United States or overseas.

Women hired during this employment spike came from varied backgrounds. Some were married and supported their families while their husbands fought in the war. Other women were single or divorced, working to independently support themselves or their children. Still others were motivated by patriotism and wanted to support the war effort. Each had her own reasons for seeking employment with the Federal government.

The majority of these women, however, would be released from duty at the end of the war despite their considerable contributions. While most experienced a reduction in force as men returned from war to take over their positions, a significant number of women were able to continue their services with the federal government and prove to the country that they were just as capable and valuable in the workforce. Lucille Atcherson was such a woman. We know that although she resigned from her position voluntarily, she noted her lack of promotion as a gender bias issue.6 Luckily, her employment file left a trail of important genealogical primary source material.

For many women, continuing on with federal employment was a necessity, particularly those who were faced with being the sole source of family income. The Service Extension Act of 1941 allowed for employment to be extended for 18 months during times related to the declaration of national peril for those who had been inducted under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 and allowed for release from service in hardship cases and some changes to reemployment rights.7 For example, the Service Extension Act allowed Jacqueline Jenkins Nye, who worked at the Department of the Navy during World War II as a code breaker, to continue employment despite having reached the temporary employment time limit. Her personnel file provided a closer look into her working life.8

All of the information contained within an OPF can offer valuable clues about the lives and employment histories of the women who filled key federal positions. For example, religious affiliations may be listed for “In Case of Death” inquiries.9 With this information, genealogists can look to local churches for records that may relate to the family and their activities. Personnel files also detail the job description and pay grade, both at the beginning of service and for every new position throughout employment. This information provides insight into the compensation for female federal workers. Post-employment address changes and updates in the files for payment and retirement needs extends the available information to beyond the workers’ tenures.

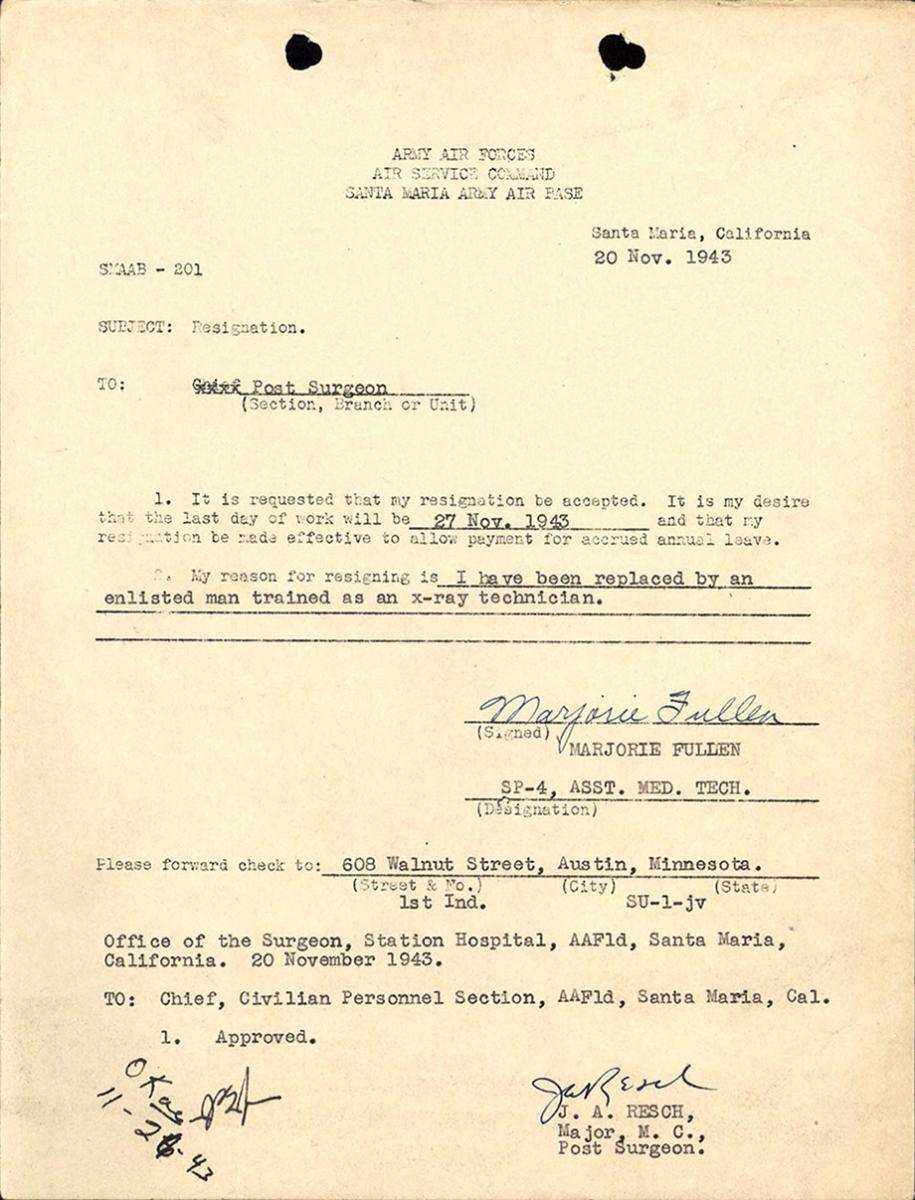

At the end of employment, the file will frequently cite the reason for resignation as well as the final pay grade. The reason can range from “reduction in force” to something more descriptive such as “I have been replaced by an enlisted man.”10 Marjorie Fullen of the Department of the Army Air Force listed both this reason and her final forwarding address at her resignation.

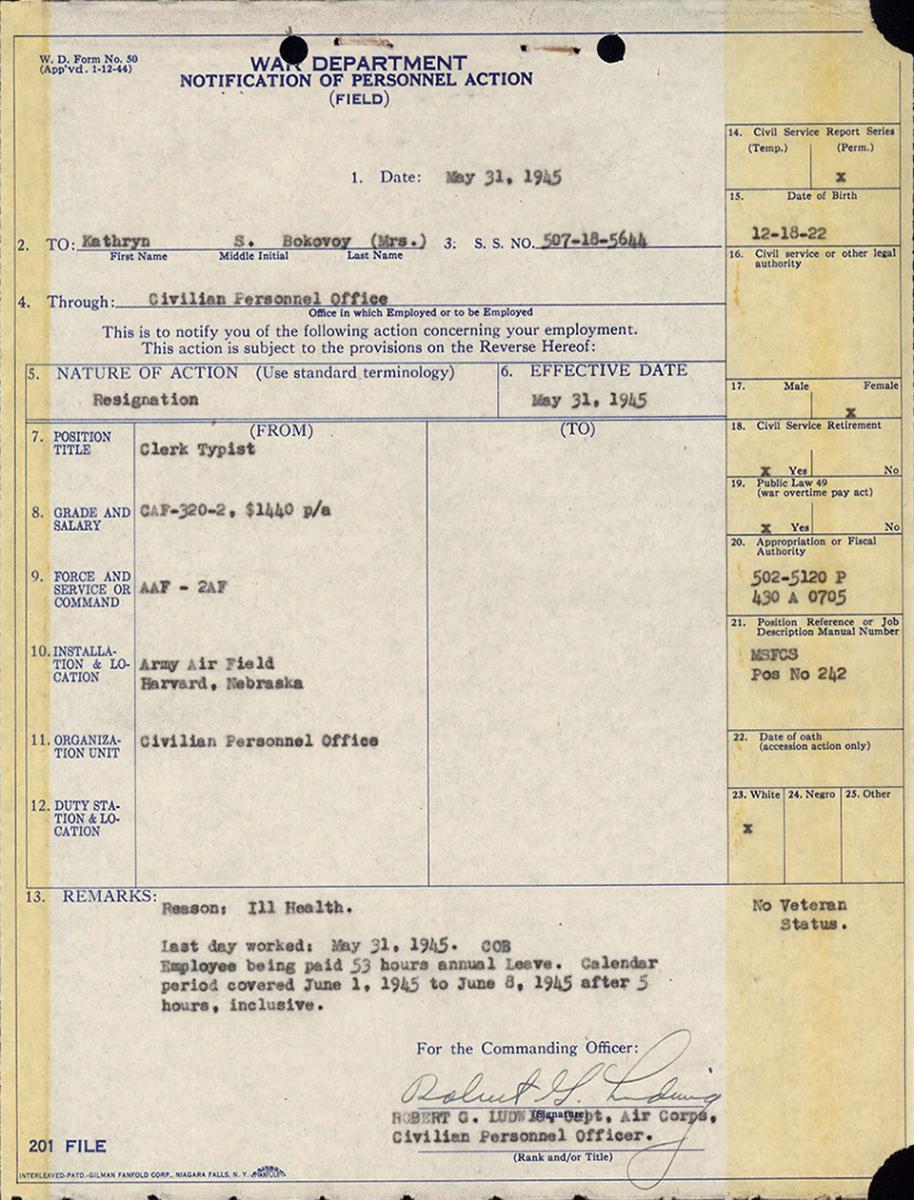

In addition, documentation includes all leave taken, and many times one may find the reason for leave, such as to care for a sick child or personal illness. Kathryn Bokovoy of the Department of the Army Air Force applied for leave several times due to her health, eventually having to resign all together.11

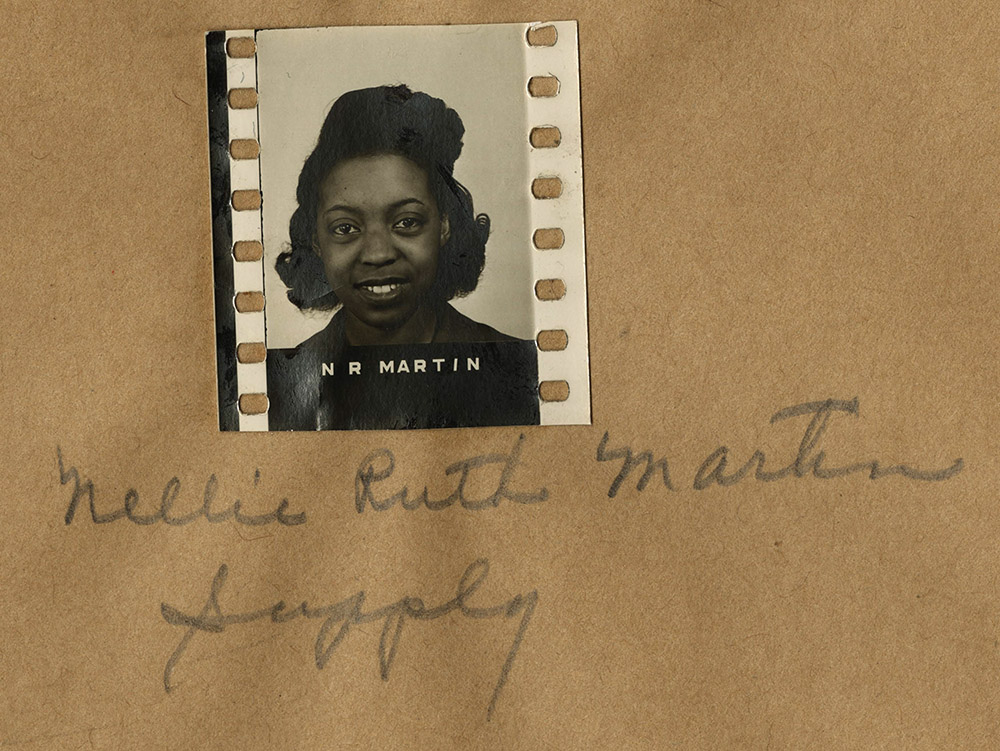

Additional types of papers found in records typically include applications, reference names and letters, changes in job title, changes in pay, correspondence from and about the employee, certifications/awards, training completed, and efficiency ratings. Information in the files sometimes include the reason for employment, such as “Urgent need” or “Current emergency,” the husband’s family’s biographic and employment information, the husband’s employment, medical leave, relevant medical notation during employment or injury on the job, badges and passes administered, pictures, newspaper clippings pertaining to the individual or a project the individual was involved in, other languages known, loyalty statements, and fingerprints taken at employment. The OPF does not contain a complete medical history, however. All of these seemingly minute details add up to a very detailed picture of employment and lives of the female federal worker during wartime.

The wealth of information out there is amazing. These examples offer a very specific look at just some of the federal agencies’ official personnel folders that are held in St. Louis. The abundance of information tucked away in these folders continues both before and after World War I and World War II and well beyond these three agencies. Though women’s history can be traditionally hard to find, civilian service records can fill in many large gaps and provide an insight into lifetimes, styles, and experiences to enrich family knowledge.

* * *

OPFs are arranged by federal agency and then alphabetically by last name with some of the series being arranged by Soundex coding of last name. Soundex is an alphanumeric code that was used to prevent common spelling deviations from creating filing errors. With this type of arrangement, it is especially important for requesters to include maiden and married names, if applicable, in their search requests for women.

Though there is no standard form to request these records, all written requests are welcome that detail the person and their federal employing agency.

To request a search for and copy of an official personnel folder, write to National Archives & Records Administration, ATTN: Archival Programs, P.O. Box 38757, St. Louis, MO 63138, or send an email to stl.archives@nara.gov. Include in your request the full name used by the person during federal employment, date of birth, Social Security number (if applicable), name and location of employing federal agency, and beginning and ending dates of federal service.

If your requested record includes employment that ends after 1951, it may be with the National Personnel Records Center’s Federal Records Center Program. The records center maintains the OPFs of former federal civilian employees whose employment ended after 1951. For these cases, mail or fax written requests (signed and dated with proof of death when applicable) to National Personnel Records Center, Annex, 1411 Boulder Boulevard, Valmeyer, IL 62295; fax: 618-935-3014.

Cara Moore is an archives technician with the National Archives and Records Administration Archival Department in St. Louis, Missouri.

Notes

1. Lucile Atcherson Curtis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucile_Atcherson_Curtis.

2. The OPFs of individuals employed before 1952 by some agencies whose personnel management systems do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) are not yet open to the public. Access to such records is restricted under the Privacy Act of 1974 (PL 93-579), and only limited types of information from these records are releasable to nonauthorized users. Once a specific record has been identified and located, the National Archives at St. Louis will make a determination on the record’s status.

3. National Archives and Records Administration, Listing of Federal Agencies of Civilian Personnel (www.archives.gov/st-louis/archival-programs/civilian-personnel-archival/official-personnel-folders-archival-holdings-table.html).

4. Social Security Bulletin, “Employment of Women in War Production,” July 1942 (www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v5n7/v5n7p4.pdf).

5. Historical Table of Federal Employment Records (www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/data-analysis-documentation/federal-employment-reports/historical-tables/executive-branch-civilian-employment-since-1940/).

6. Lucile Atcherson, Department of State Official Personnel Folder, gender bias dispute.

7. Service Extension Act of 1941 (www.gao.gov/9/fl0040883.php).

8. Jacqueline Jenkins Nye, Department of the Navy Official Personnel Folder, Extension of Employment notice granted due to Service Extension Act.

9. Mamie Oatney, Department of the Navy Official Personnel Folder, Religion listed.

10. Marjorie Fullen, Department of the Army Air Force Official Personnel Folder, replaced by a man.

11. Kathryn Bokovoy, Department of the Army Air Force Official Personnel Folder, resignation due to ill health.