Remembering Vietnam

A New Exhibit at the Archives Helps Us See the Causes and Impact of the War

By Alice Kamps | Prologue magazine, Fall 2017, Vol. 49, No. 3

Mai Elliott’s earliest memory, like many people’s, is a sensory one. She was alone in a room in her house when the windows began to rattle. She put her tiny hands on the glass to feel the vibrations. She can feel them to this day. Later she learned what happened: an allied bomb strike.

It was World War II and her family lived in Nam Dinh, an industrial city and military target on the north coast of Vietnam. Mai also remembers being annoyed when her playtime was interrupted by the air-raid sirens. She was regularly swept up and raced to the bomb shelter with her parents and siblings.

I interviewed Mai in her home in Claremont, California, where the sound of raccoons on the roof was the only likely interruption. Surrounded by antiques and artifacts from her travels with her husband, historian David Elliott, she served macaroons to the crew filming our interview for an exhibition and told us her memories of the Vietnam War.

At times a broad smile lit her face, and it was easy to imagine her as a young Vietnamese exchange student at Georgetown University, her hair teased into a bouffant tribute to her idol Jackie Kennedy—a hairstyle that would scandalize her traditional parents when she returned to Vietnam.

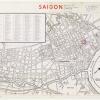

Beginning November 10, 2017, highlights from Mai’s interview will appear in “Remembering Vietnam,” a new exhibition in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. The exhibition draws on the Archives’ vast repository of Vietnam War records spanning the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, from the Office of Strategic Services’ training of Viet Minh guerrillas during World War II to the frenzied evacuation during the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The Vietnam War: How to Remember It?

“Remembering Vietnam” presents both iconic and recently discovered National Archives records related to 12 “critical episodes” (important events and turning points) in the Vietnam War. These historic documents, recordings, and images trace the policies and decisions made by the architects of the conflict and help untangle why the United States became involved in Vietnam, why it went on so long, and why it was so divisive for American society.

“Remembering Vietnam” presents both iconic and recently discovered National Archives records related to 12 “critical episodes” (important events and turning points) in the Vietnam War. These historic documents, recordings, and images trace the policies and decisions made by the architects of the conflict and help untangle why the United States became involved in Vietnam, why it went on so long, and why it was so divisive for American society.

The Archivist of the United States, David Ferriero, himself a Vietnam veteran, was determined to mark the 50th anniversary of the height of the Vietnam War with an exhibition.

Ferriero shares the sentiment Ken Burns expressed about his upcoming PBS series, The Vietnam War: “There was no way we could avoid telling this story.” The National Archives’ veritable mountain of evidence continues to yield discoveries and to serve as the basis for new interpretations.

A steady drip of declassification contributes to this evolving scholarship. Much new scholarship has emerged recently as foreign archives have begun to open to researchers, providing a more rounded perspective on the war.

But what is the “story” of the Vietnam War?

Beyond describing it as a disaster and a tragedy, many Americans disagree about how to remember the war.

Soldiers marching through a rice paddy

Members of Company B, 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry Regiment (Wolfhounds), 25th Infantry Division, cross a stream approximately 9.3 miles southeast of Nui Ba Den during search-and-clear operations near Fire Support Base. (National Archives, RG 111)

Is America Always the “Good Guy”?

Was it winnable or doomed to fail? Was it immoral or a worthy cause? What lessons should be drawn from it?

Was it winnable or doomed to fail? Was it immoral or a worthy cause? What lessons should be drawn from it?

The debate rages on unabated: a memorial design inspires congressional opposition, a Department of Defense Internet timeline occasions the publishing of a protest letter in the New York Times, and conference sessions are met with “prebuttals.” The war created a rift in society—a rift like that caused by the Civil War, which seems only to deepen with time. At this time of extreme political polarization we might consider whether Martin Luther King was correct when he said, “if America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read ‘Vietnam.’”

At the core of the noble cause or immoral war question is a question about the identity of the United States. If the verdict on the war is that it was unjust, we must consider whether we can hold on to the conviction that Americans are always the “good guys.”

President Ronald Reagan forcefully contradicted this assessment in his 1988 remarks at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., saying, “After more than a decade of desperate boat people, after the killing fields of Cambodia, after all that has happened in that unhappy part of the world, who can doubt that the cause for which our men fought was just?”

Others take a different view.

In the Ken Burns documentary, Vietnam War veteran and author Karl Marlantes said, “Sometimes I think if we thought we weren’t always the good guys we might actually get into less wars.”

Life Magazine Asserts “The American Century”

Interestingly, the origins of the American self-concept as global guardians of democracy and freedom is also tied to Vietnam. Historian David Elliott, Mai’s husband, introduced me to the little-known early intertwining of the destinies of Vietnam and the United States.

“The Japanese invasion of Tonkin (Northern French Indochina] in September 1940 triggered a series of U.S. economic sanctions which ultimately led to Pearl Harbor,” Elliott told me. “This was the first time any part of the obscure French colony of Indochina had come to the attention of the American public. The question of whether or not the United States should resist this aggression . . . was a central focus on the most influential statement of America’s Twentieth Century destiny ever written, the Life magazine editorial in February 1941 by editor-in-chief Henry Luce titled ‘The American Century.’”

Luce asserted that the United States had both the right and the moral obligation to use its military and economic power to promote its higher ideals of freedom and democracy around the world, “to accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.” Luce’s “American Century” article was highly influential. But his concept of the United States as the global Good Samaritan was called into question by the Vietnam War and is an area of contention in the battle over its memory. This struggle is not unique, according to the author Viet Thanh Nguyen.

In his recent book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of the War, Nguyen writes that “all wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” I spoke to him at the University of Southern California, where he is a professor of English and American studies and ethnicity.

After Guns Are Silent, Battles over Memory Begin

Nguyen’s family escaped during the fall of Saigon in 1975 and came to America by way of Guam. They landed in a refugee camp in Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. Refugees needed an American sponsor in order to leave the camp, but none could be found to take his entire family. Like Mai, Viet’s earliest memory is related to war and trauma—howling as he was taken from his parents to live with strangers in a strange land. He was four years old.

“Wars are not finished simply because ceasefires are signed and the bullets stop firing,” said Nguyen, whose fast-paced speech spools forth in perfectly formed, complex paragraphs. “Continuing struggles over what they mean for individual and national memory remain really resonant and powerful,” he said. “Archives are also a part of this conflict over memory because what gets archived, what is deemed important enough to be put in an archive is a subject that is up for debate.”

During an interview, Nguyen counseled us to do justice to the people whose stories do not make it into the archives “by grappling with the larger meaning of the war, beyond how it was fought by soldiers but how it involves entire nations and civilians as well.” In order to expand our exploration of the war beyond how it was fought by soldiers and orchestrated by the government, “Remembering Vietnam” will include the stories of people with direct experience of the 12 critical episodes. Their filmed interviews, including Mai’s and Viet’s, will relate some of the human consequences of the war and provide a variety of lenses—both American and Vietnamese—through which to view the history.

Marines come ashore near Da Nang

Marines come ashore near Da Nang Air Base on March 8, 1965. Vietnamese officials only learned of plans to introduce American ground troops as 3,500 Marines were wading onto its shores. (National Archives, RG 127)

Young Generations Know Little of the Vietnam War

Stories told by American and Vietnamese civilians, veterans, peace activists, journalists, and historians will be edited together with historic film footage to be screened in three small theater spaces within the exhibition.

One of the historians featured in the mini-documentaries is Edward Miller, associate professor of history at Dartmouth College. Students come to Miller’s popular Vietnam War history class with a lot of interest, a sense that it is important, but very little understanding about what it was about. Sixty-five percent of Americans are under age 45 and therefore were born after the war ended.

In 2013, Gallup polled Americans about whether they thought sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake. For the first time, a majority of one group said no. It was the 18- to-24-year-olds. According to Miller, young Vietnamese people, like their American counterparts, know little about the war. Many people in both countries, even those who lived through it, share basic questions about this critical historical chapter.

It is also true that public awareness of some of the most basic facts about the war is limited. While many could tell you that more than 58,000 Americans died in the war, few could report the number of Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians who were killed (approximately four million). The fact that the war resulted in 1.6 million Vietnamese refugees is also surprising to many.

The 12 episodes covered in the exhibition were selected to provide visitors with a sense of the basic contours of the war, the major controversies it kindled, and its effects on the countries involved. By exploring the policies and personalities behind the decisions that led to, escalated, and ultimately withdrew the United States from the war, the exhibition seeks to shed light on why America became involved, why the war went on for so many years, and why it was so controversial.

Origin of Vietnam War Dates to Truman Era

The origins or “embers” of the war, as Harvard historian Fredrik Logevall calls them, occurred long before the American war with Vietnam started. Beginning with President Harry S. Truman’s inaction in the face of the French move to recolonize Vietnam, the episodes proceed through President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s backing of South Vietnamese leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, and President John F. Kennedy’s escalation of financial and military aid. They continue into the years we count as the Vietnam War, 1965–1975.

“I am not going to lose Vietnam,” President Lyndon B. Johnson said in committing the United States to direct intervention in 1965, “I am not going to be the President who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went.” U.S. troops remained in Vietnam another four years under President Richard M. Nixon, until the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement in 1973. The episodes culminate with the Fall of Saigon under President Gerald R. Ford in 1975.

The closing section of “Remembering Vietnam” touches on aspects of the war’s legacy. These include stories about the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, the importance of National Archives records to American veterans, Vietnamese Americans and the refugees, and current relations between the United States and Vietnam today.

At the end of my talk with Mai Elliott, I asked her what she wanted people to remember about the Vietnam War, the last in a series of wars that consumed the first two decades of her life and divided her family.

I think I would like them to remember what it was like during the war. The destruction, the killing, the violence, and think about what it is now. At peace. That was my feeling when the war ended. I didn’t care who won. I didn’t care who lost. I only cared that the war ended and that Vietnam now experienced peace.

Visiting the Exhibition at the National Archives

Visitors to “Remembering Vietnam” will have the opportunity to see a fascinating and varied selection of records from the National Archives and its Presidential libraries. The records on display help fill the gaps in our collective memory about what happened and why. They illuminate the series of choices, strategies, and personalities that resulted in the United States’ 35-year involvement in Southeast Asia. Some of the foremost Vietnam War historians add context and insight through their commentary.

Preeminent scholars recommended historic items they considered critical to understanding the conflict and its origins. Spanning 1918–1975, they include posters, artwork, telegrams, radio intercepts, photographs, artifacts, official documents, and letters.

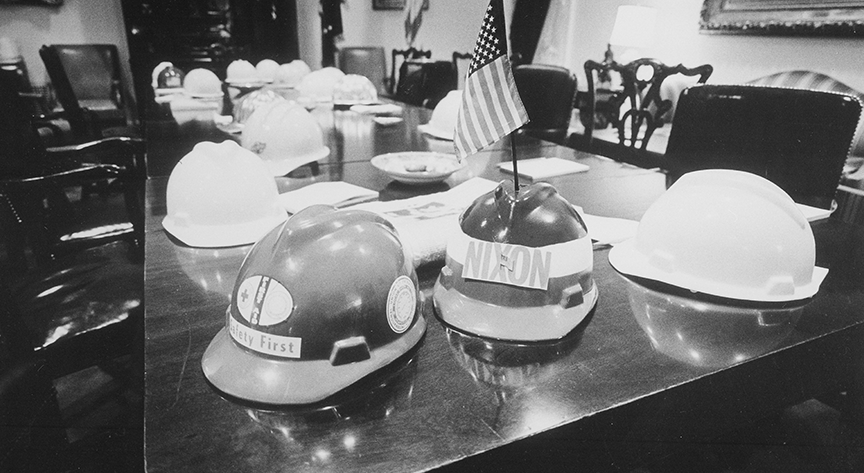

Of special interest are the audio recordings, some of which have only recently been declassified. The exhibition includes several listening stations, including an “Oval Office Listening Area,” where visitors can pick up one of three phones to hear conversations held by Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon.

“The tapes show,” Logevall explained during his interview, “how uncertain officials are of which way they are going to go. . . . It helps us understand that for the decision-makers of the past, the future was merely a set of possibilities.”

The exhibition also is an opportunity to hear stories from a variety of perspectives. Everyday people whose lives were forever impacted by the conflict—some voluntarily, some involuntarily—share their experiences.

At a kiosk, visitors will be able to submit their own thoughts about what happened and how it affected them. Selections of those contributions will be displayed in the exhibition for visitors to read. The exhibition will not resolve questions about whether the war was winnable, a just cause, or what lessons should we draw from it. But perhaps it will inspire new questions, questions with answers that do not lie on one side or the other of an ideological divide.

Learn More About . . .

Learn More About . . .

A journalist’s view of Vietnam over the years.

U.S. fatalities in the Vietnam War, listed by state.

Alice Kamps is the curator of “Remembering Vietnam.” Her previous exhibits and displays at the National Archives include “Our Nation’s Founding Documents,” “The 1297 Magna Carta,” and “What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?” Her publications include The Charters of Freedom at the National Archives and the exhibit catalog What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?

Alice Kamps is the curator of “Remembering Vietnam.” Her previous exhibits and displays at the National Archives include “Our Nation’s Founding Documents,” “The 1297 Magna Carta,” and “What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?” Her publications include The Charters of Freedom at the National Archives and the exhibit catalog What’s Cooking, Uncle Sam?