Searching for Captain Blye

Exploring Maritime Records at the National Archives at Boston and Beyond

Spring 2017, Vol. 49, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By Andrew J. Begley

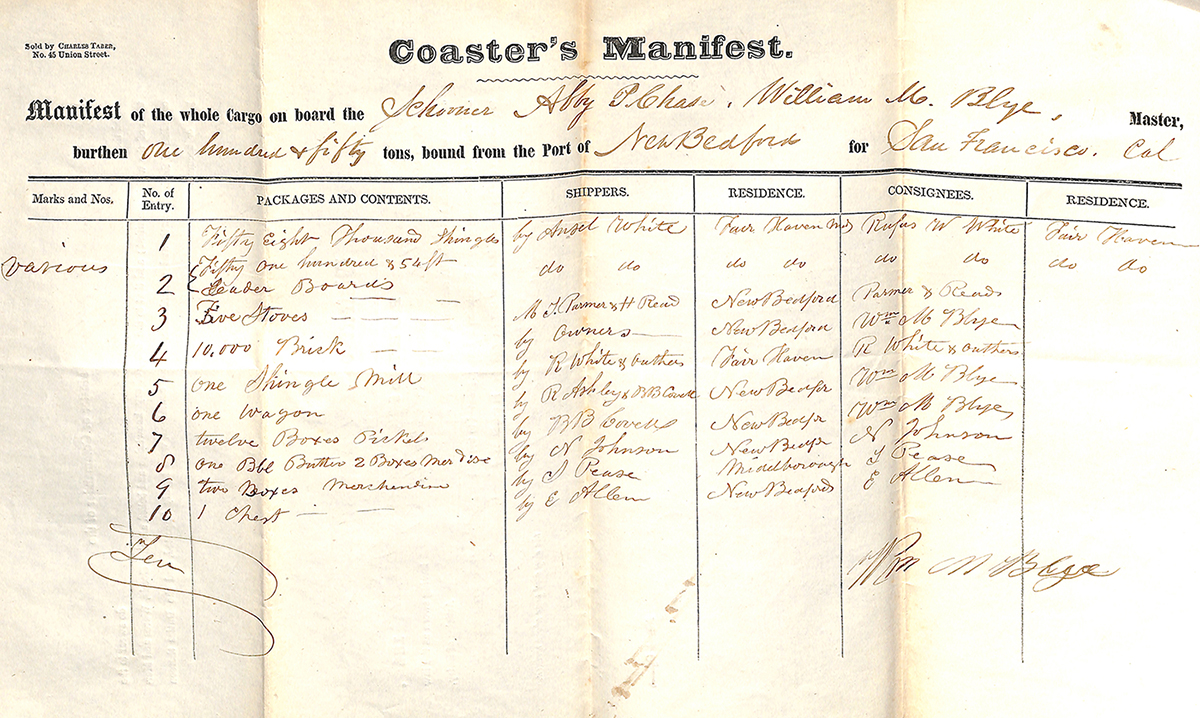

Capt. William Blye set sail from New Bedford, Massachusetts, on November 24, 1849, heading for San Francisco with a crew of 11 men aboard his schooner Abby P. Chase.

The gold rush was in full swing in California, and the boom towns were in need of all kinds of previously unavailable goods. What exactly did they need? Well, Blye was betting that they would need ovens, bricks, shingles, wagons . . . and pickles.

These goods and more were listed on the manifest Blye lodged with the customs house in New Bedford before setting sail on the difficult journey around South America.

When most of us consult maritime records looking for our ancestors, our first (and often only) stop is usually passenger lists. When did our ancestors arrive on these shores? Who did they travel with? Where were they coming from? These facts are touchstones on our genealogical journey.

For many of our ancestors, however, their journey to America was just one brief chapter in lives lived primarily at sea. In New England, where fishing, whaling, and coastal trading were such vital drivers of the local economy, a host of maritime records can provide tantalizing glimpses into the everyday lives of those who plied these trades.

A Variety of Sources for Personal Information

Ship captains, crew members, fishermen, and whalers came to the attention of federal record keepers in a variety of ways: through crew lists and registers kept at customs houses, through life-saving station logs and wreck reports following tragedies at sea, and through the records of marine hospitals created for them throughout the country.

Depending on the time period, these records can be found in any of the following record groups at the National Archives: Records of the U.S. Coast Guard, 1785–2005, Record Group (RG) 26; Records of the U.S. Customs Service, 1745–1997, RG 36; and Records of the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation, 1774-1982, RG 41.

A word of warning: many of these maritime records are underused because barriers to entry are fairly high. Indexes, when they are available, usually refer to individual volumes of records rather than whole series. In most cases, a research visit to the appropriate National Archives facility will be necessary. To get started, you will need an individual’s name, year of birth, place of residence (or the nearest port), and a date range for when you believe the person may have been involved in the maritime trade. Knowing the name of a ship or ships the individual sailed on will increase your chances of success dramatically.

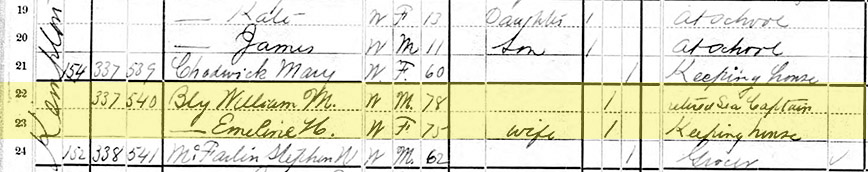

Luckily, with the exception of ship names, most of this information is readily available through federal census records. A search of census schedules through National Archives partner sites such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org is a great starting point. In 1850, the census began to include occupations, and mariners were listed variably as “seaman,” “ship captain,” “mariner,” “master mariner,” and “licensed ship master.”

Once you have some basic information to work with, the types of records that you may find will depend on the individual’s role in the industry. The average mariner may show up in crew lists and seaman’s registers, while captains and ship owners will also be found in ship’s manifests, licenses, and records of vessel sales. With some digging, it is possible to piece together these records to tell the story of an individual’s life at sea and gain insight into the role the maritime trade played in shaping their community.

Searching for Captain Blye in Customs Service Records

So who was the Captain Blye who was setting sail for gold-rush California? William M. Blye (not the William Bligh of Mutiny on the Bounty fame) was a master mariner born in Smithfield, Rhode Island, in 1802. Blye would captain and own several ships based out of Bristol, Rhode Island, during a career that would last into the 1860s.

A search for Blye in the federal census finds him living in Bristol in 1850 with an occupation of “ship master.” By 1880, Blye is living in New Bedford, Massachusetts, now as a “retired sea captain.”

During the mid-19th century, Blye captained several ships that sailed out of New Bedford, including the Abby P. Chase and the Francis A. Seward. A search for records related to these vessels and to Blye himself in the Records of the U.S. Customs Service (Record Group 36) highlights the difficulties and rewards of this type of research.

While the Francis A. Seward has proven quite elusive, several ships’ manifests for the Abby P. Chase can be found in in the series “Inward and Outward Coastal Manifests, 1808–1939” for the port of New Bedford. In addition to the voyage to San Francisco in 1849, the Abby P. Chase also sailed to New Orleans in 1848 with a cargo of oil and gunney bags.

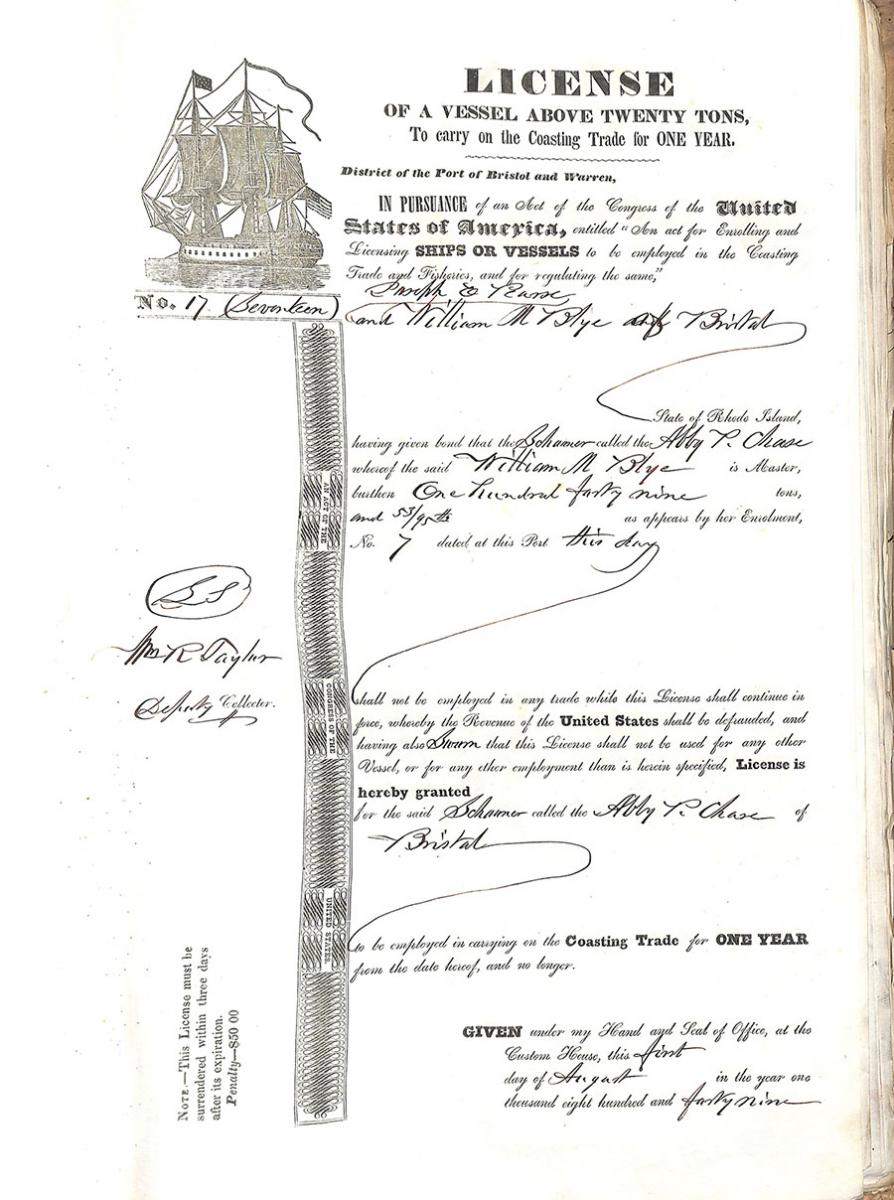

Blye and the Abby P. Chase can also be found in a series titled “Licenses of Vessels above 20 Tons for the Coasting Trade” for Bristol, Rhode Island. As a part owner of the Abby P. Chase, Blye was required to apply for a yearly ship license from the Customs Service. These licenses were issued in several general categories, including for coastal trade, foreign trade, and fishing, and were also organized by vessel size (over or under 20 tons).

Having previously located the manifest for the Abby P. Chase, we know that the vessel had a berth of 150 tons. We also know that it was engaged in the coastal (“coasting”) trade. These two clues help us locate the series that may hold records of the licensing of the vessel.

The license indicates that Blye was the co-owner of the Abby P. Chase with Joseph Pierce, and it allows the vessel to carry on the coastal trade for one year, beginning on August 1, 1849. Because these licenses are found in the records of customs houses for specific ports, it is important to know in what port the ship was registered. The manifests for the voyages to San Francisco and New Orleans were located in records for New Bedford, the port of departure. The license, however can be found in records for Bristol, where Blye lived and registered the Abby P. Chase.

What About Information on the Crew Members?

While manifests and licenses are good sources of information on ship captains and owners, how do we learn about the crew members they employed? A crew list would be a logical place to start, but in the case of William Blye’s vessels, there do not appear to be any crew lists for the Abby P. Chase or the Francis A. Seward within the holdings of the National Archives at Boston. The documents may not have survived or may have been deposited at a local museum or historical society before the establishment of the National Archives in 1934.

The hazards of early record keeping were such that only a single crew list survives from the port of Bristol, Rhode Island, for this time period. The records for New Bedford are much more extensive but still do not contain any information on Blye’s ships.

In addition to crew lists, these types of records may contain information on individual mariners.

Seamen’s Registers, also known as Registers of American Seamen or Seamen’s Protection Registers, list the name, age, place of birth, and physical description of seamen who were issued Seamen’s Protection Certificates. These certificates were issued to mariners in response to British impressment during and after the War of 1812. (In most cases, the National Archives has only the registers recording their issuance, not the original certificates.) An index to these registers for New England ports can be found online through Mystic Seaport.

Proofs of Citizenship were also created in response to the dangers of impressment into the British Navy and were required to issue a certificate of citizenship to seamen. The proofs are sworn statements as to the citizenship of the individual. An index of these proofs of citizenship is searchable in the online National Archives Catalog.

Marine Hospital Records document hospitals founded at ports throughout the country beginning in 1789. A percentage of seamen’s wages would be withheld each month, with the money going to the support of sick and injured mariners. Records include Hospital Returns, which document wages withheld, and include information on individual vessels and their masters and crew.

Wreck Reports and Life-Saving Station Logs are found in both the records of the U.S. Customs Service and the U.S. Coast Guard. These records can be used together to locate information on individuals who were killed in shipwrecks or accidents at sea.

Wreck reports were submitted to the Customs Service following shipwrecks and strandings and include information on the vessel and its cargo, the weather conditions, and the names of crew members lost. If assistance was provided by a life-saving station (run by Coast Guard precursors the Revenue Marine Service and U.S. Life-Saving Service), life-saving station logs can provide further contextual information.

When considering maritime records for genealogical research, it is important to think about the types of information you hope to discover and the time and energy that will be required to make significant progress. If you simply want to locate where an ancestor lived or was born, combing through boxes of crew lists might not be the best approach. However, if you are interested in using customs and other maritime records to help paint a broader picture of the lives lived by these individuals, this research can be extremely rewarding.

Our search for William Blye in the records of the U.S. Customs Service not only provides information on where Blye lived and traveled, it gives us the opportunity to explore broader trends in topics ranging from life in New England in the mid-19th century to maritime trade and westward expansion. It is at this intersection of genealogy and broader historical research that we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the lives of our seafaring ancestors.

Andrew J. Begley is an archives technician at the National Archives at Boston. He received his M.A. in history and M.S. in library and information science from Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts.

Note on Sources

Customs and Coast Guard records for New England ports are located at the National Archives at Boston. Maritime records for other ports are available at various National Archives locations throughout the country. A search in the National Archives Catalog for the appropriate port and record type is the best place to start. Search results will include contact information for the location that holds that series of records.

The author consulted the following records in Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36 at the National Archives at Boston:

Crew List, Acushnet, January 2, 1841; New Bedford—Crew Lists of Whaling Vessels, 1820–1915;

Manifest, Schooner Abby P. Chase, October 21, 1848; New Bedford—Inward and Outward Coastal Manifests, 1808–1939; Box 8;

Manifest, Schooner Abby P. Chase, November 24, 1849; New Bedford—Inward and Outward Coastal Manifests, 1808–1939; Box 8; and

License, Schooner Abby P. Chase, August 1, 1849; Volume 17, 1844–1854; Bristol, RI—Licenses of Vessels above 20 Tons for the Coasting Trade, 1802–1885.

Also useful was William Richard Cutter’s Historic Homes and Places and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of Middlesex, volume 4 (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1908).