12,000 Marks for Texas

Germans Are Asked to Help Victims of Historic Hurricane in 1900

Spring 2017, Vol. 49, No. 1

By Robert C. Greiner

© 2017 by Robert C. Greiner

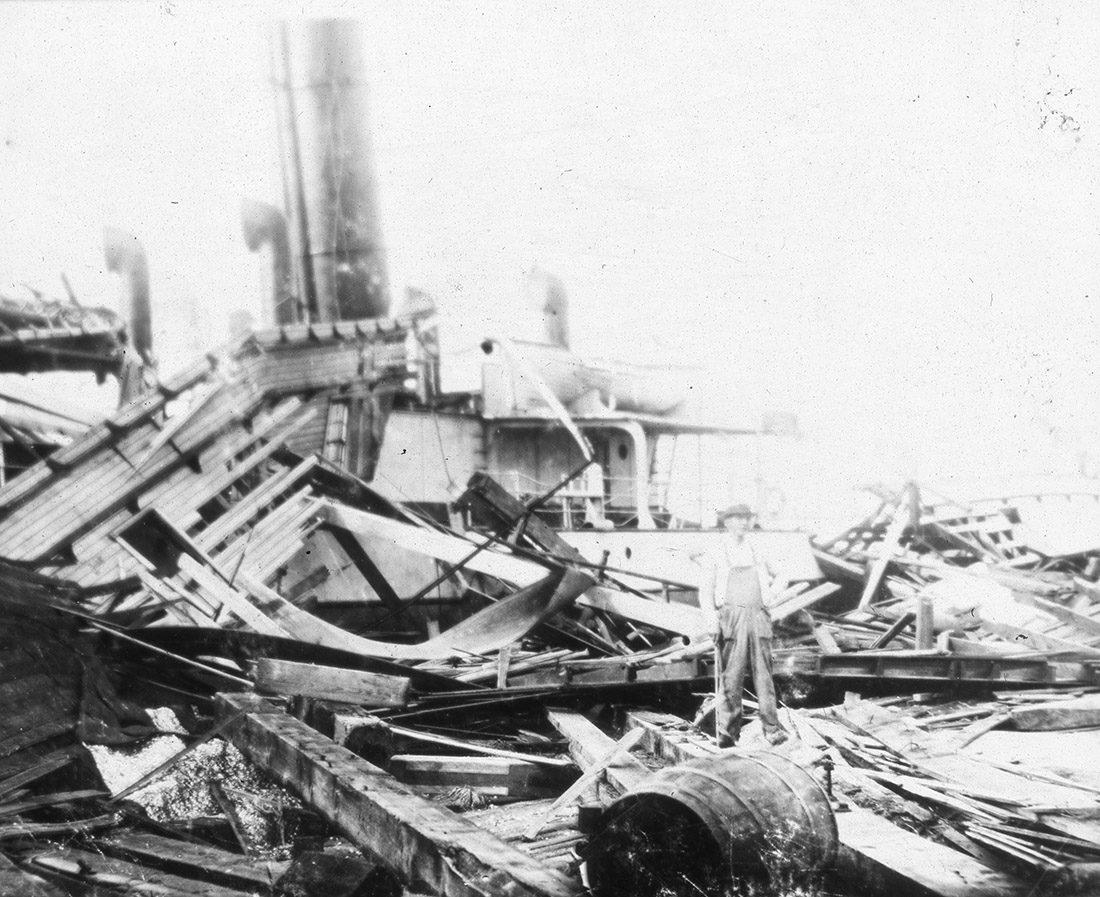

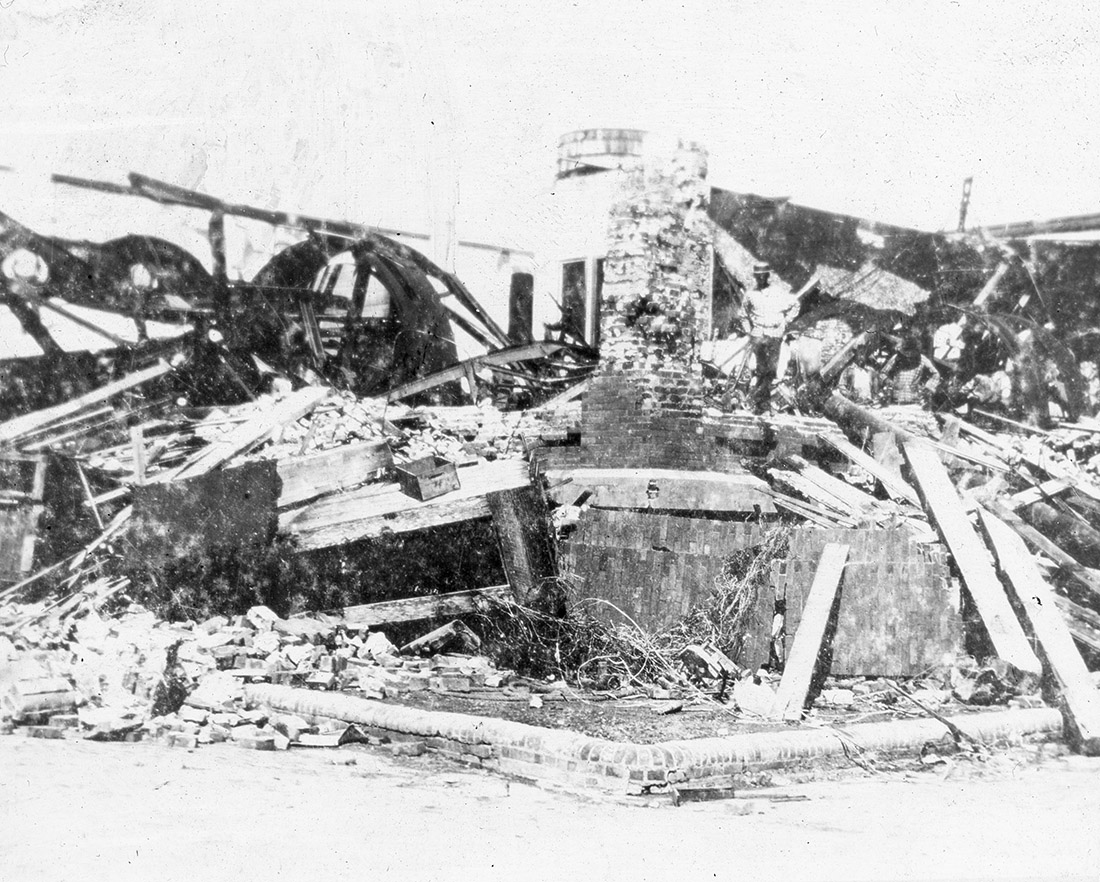

On September 8, 1900, a powerful hurricane made landfall directly at Galveston, Texas. The storm inundated the city, which lay on an island only eight feet above sea level, and virtually leveled it.

The devastation continued as the storm made its way inland. Although the estimates vary, as many as 8,000 people, and perhaps more, died as a result of the storm.

Citizens of the United States quickly responded by sending assistance and supplies to Texas as soon as it was possible. Relief funds were established in many cities to collect money to help the survivors.

The impulse to help the storm victims reached far across the continent and beyond the Atlantic Ocean, even to the German city of Frankfurt am Main. The United States consulate in Frankfurt handled trade relations between companies in the United States and surrounding regions in Germany. It also provided services to U.S. citizens residing in or visiting the area. At the time of the Galveston hurricane, Richard Guenther, the consul general since 1899, had just left for an extended leave to the United States, and Vice Consul Simon Hanauer was acting in his place. Apparently based on his own humanitarian motives and through no official request, Hanauer established a relief fund in Frankfurt to benefit the unfortunate Texan people.

Hanauer had a multipronged plan to encourage donations to his fund. He enlisted the aid of an international banking firm Lazard Speyer-Ellissen to help collect money. They published a joint announcement in the Frankfurter Zeitung on September 18 asking for donations, which they both signed. The announcement read:

Call in Aid of the Texas Sufferers. Terrible storms and inundations have devastated the State of Texas and particularly the City of Galveston. The destruction of thousands of human lives is already a mournful fact, the full extent of the calamity cannot be estimated at present. Relief committees have been formed in all American cities to alleviate the suffering. The undersigned also solicit liberal contributions for the sufferers and will gladly accept donations.

The Chamber of Commerce of New York will take charge and make proper use of all amounts transmitted to it by us.

Another announcement in English was published September 19 in the Frankfurt General Anzeiger.

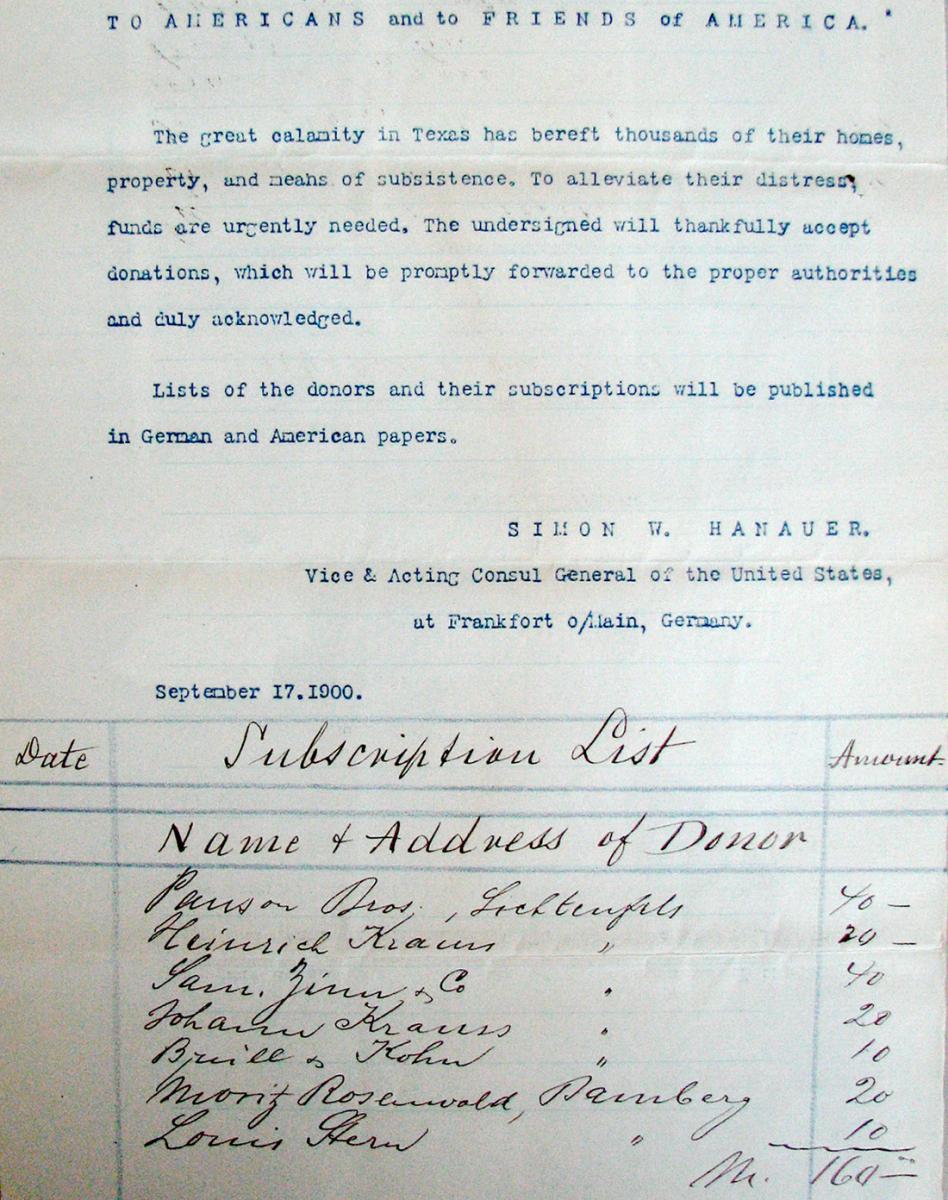

To Americans and Friends of America

The great calamity in Texas has bereft thousands of their homes, property, and means of subsistence. To alleviate their distress, funds are urgently needed. The undersigned (as also the banking firm L. Speyer-Ellissen) will thankfully accept donations which will be promptly forwarded to the proper authorities. All sums sent in will be duly receipted for, and acknowledged in German and American papers.

Hanauer contacted companies in the area that conducted business with United States companies, promising to publish the names and amount contributed in both Frankfurt and American newspapers. The companies would benefit from the publicity, and others might be encouraged to match the amount contributed. Hanauer believed that the publicity would help to strengthen relations between German and American citizens.

Several hundred American citizens lived in the area around Frankfurt. Others visited to take advantage of the numerous spa towns or to attend university. Hanauer wrote to several pastors who served these expatriates, asking them to make their congregations aware of the relief fund.

Finally, Hanauer sent a circular letter to each of the 16 other consulates of southern and western Germany that reported to the consul general at Frankfurt. The letter included some of the same language used in the English newspaper announcement. He asked the other consuls to do what he had done in Frankfurt: publish the announcement, enlist support from businesses and banks, and collect money to forward to Frankfurt.

Pleas for Assistance Get Lukewarm Responses

On September 18 Hanauer advised his superiors at the State Department of his plan. He included copies of announcements that appeared in Frankfurt newspapers and explained that he had arranged for the German banking firm to hold the funds collected. Once money accumulated in the account, he would transfer money to the State Department. (Curiously, he did not mention the New York Chamber of Commerce.) Due to the delay in sending mail via steamships through Bremen, the letter did not reach Washington until September 28.

Replies soon began arriving in Frankfurt from the other consuls. Several of them explained that they had already donated to a fund established by Consul Warner of Leipzig. His request arrived several days before Hanauer’s. Other consuls offered one of several excuses to explain why they did not expect any donations. In some cases there were few Americans living in their region. Others suggested that the German people were not interested in American problems, or that they thought Americans were rich and did not need their help. At least half of the consuls Hanauer contacted did not collect a single contribution.

Consul Edward Ozmun from Stuttgart best summed up the thoughts that the others had. He stated that he was opposed to the idea of asking Germans for contributions. He thought it demeaning that American citizens would ask those of another country for help. He wrote:

We can give in abundance to starving India, to starving Russia or to Germany when her war taxes impoverish the people if that time should ever come, but we are too rich, powerful and too thoroughbread [sic] to ask from anyone, and I am one who didn’t.

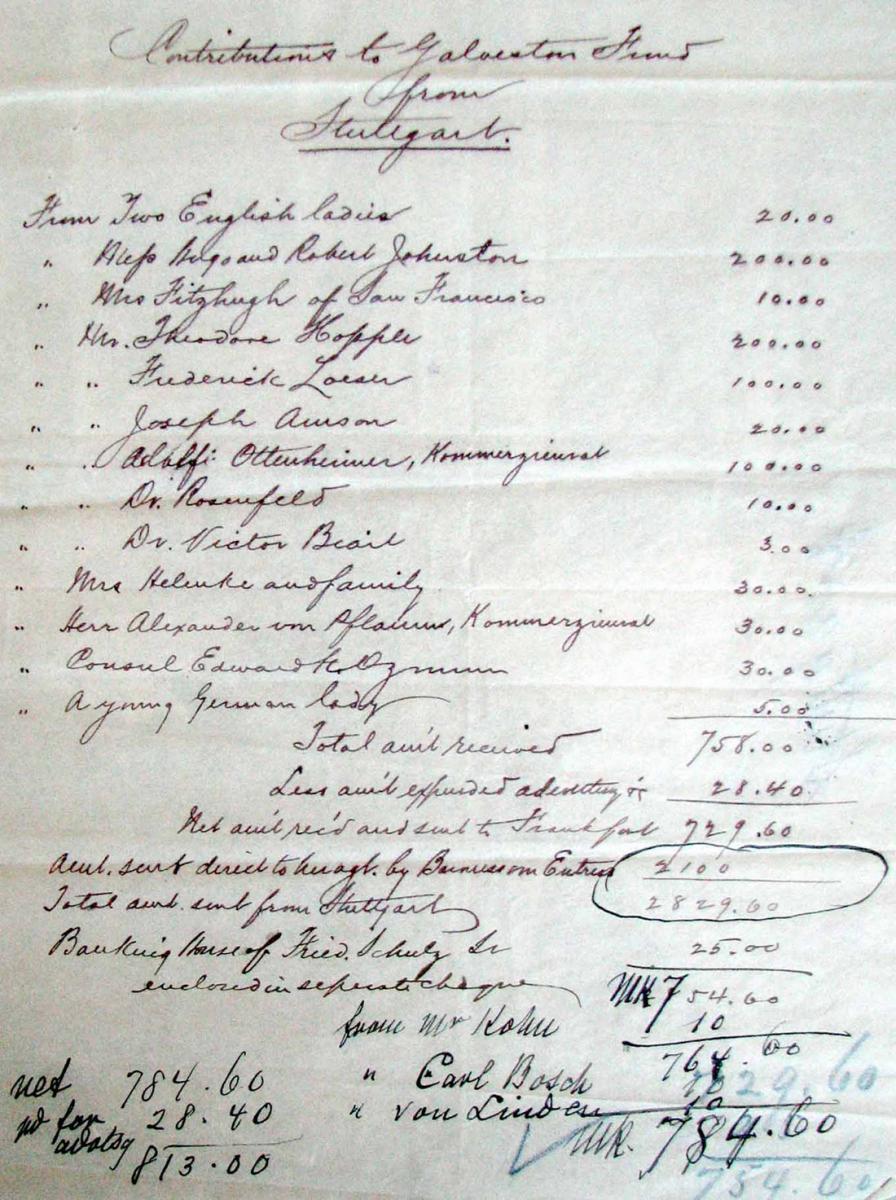

Ozmun also complained that few Germans were willing to contribute. Only one bank gave money, and no newspapers were willing to print the announcement for free, or to contribute. Despite his pessimism and lack of effort, he was able to collect over 800 marks, mostly from Americans in the Stuttgart area. He sent these donations to Hanauer in several checks. An American woman, the Baroness von Entress, donated $500 but insisted on sending it directly to her agent in Galveston, apparently not trusting government channels to get the money to the right place.

Hanauer replied to several of the pessimistic consuls and asked them to send him a list of the companies in their region who had business ties with the United States. He received substantial lists from Cologne, Freiburg, and Mainz. Presumably Hanauer contacted these firms himself to encourage their participation.

Contributions began arriving on October 3. Consular Agent Leopold Blum from Neustadt (west of Heidelberg) sent a letter naming two donors, accompanied by a postal order for 30 marks. Consul Julian Phelps from Crefeld simply returned Hanauer's letter with the names of two donors written at the bottom, amounting to 45 marks.

Louis Stern, the commercial agent in Bamberg, noted in his letter that some of his constituent companies had already donated through their branches in New York or to the consulate at Leipzig. He annotated Hanauer's original letter with a list of seven donors from Lichtenfels and Bamberg, including himself. He transmitted the 160 marks via postal order.

Hanauer received several letters between October 3 and November 2 from Gustav Weber, the consul at Nuremberg. Each contained a list of donors, eventually amounting to 40 in all. Weber also mentioned that he had already contributed to a fund at Leipzig. He eventually sent a total of 788.30 marks via postal order.

American Consul Cites Difficulty in Getting Germans to Contribute

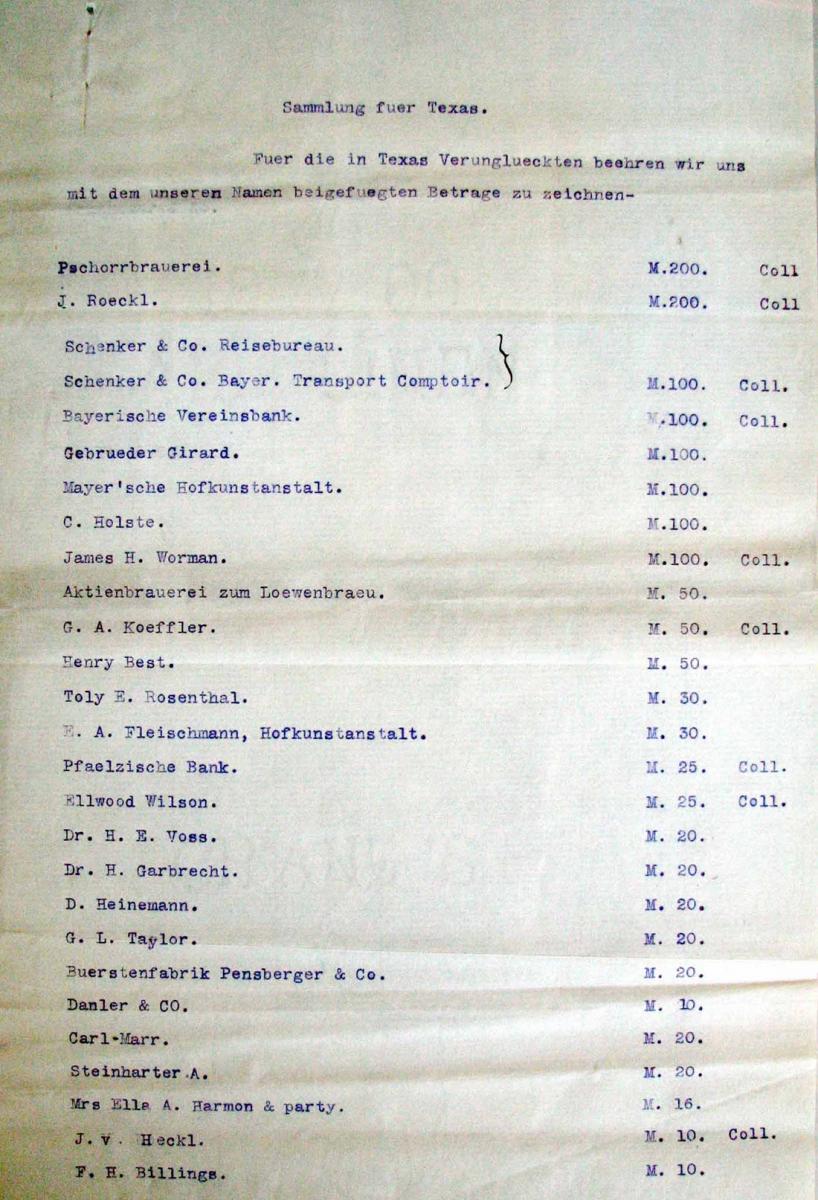

The champion fundraiser was James Worman, the consul at Munich. He collected over 4,000 marks from more than 100 contributors. He chose to send the money to Hanauer in several checks between October and December. Worman summarized the donors in several lists, some of which were typed and sorted by the amount contributed. He also provided an accounting of the money collected and checks sent so that Hanauer would be clear about the totals.

In the extensive correspondence between the two consuls during this time, a frequent topic was how much work they were both expected to complete with insufficient help. Despite the amount of money he finally collected, Worman also complained in one letter about the difficulty he had getting Germans to contribute. The results, however, show that he eventually was successful.

Hanauer also kept his own list of donors, as did the banking firm Lazard Speyer-Ellissen. They had initially agreed that both of them would accept donations, and the Frankfurt newspaper announcement stated that. Hanauer intended that they would eventually publish the names of all donors in the papers. However, at some point a disagreement arose, and the bank refused to give Hanauer their list of names. They only provided him the total amount that they collected. In the end, both published their own lists of contributors.

On November 16 Hanauer published a list of contributors from all consulates in a Frankfurt newspaper. He sent a letter with a copy of the article to his friend Consul Worman at Munich. The original clipping from the newspaper was found in Munich records. The article indicates that it was the third list of Frankfurt contributors published. Only one such handwritten list appears in the Frankfurt file, leading to the conclusion that not all of the Frankfurt lists survived.

The final remittances from the other consulates were received in Frankfurt by early December. Hanauer prepared a statement of the contribution account, detailing the amounts received, expenses, and checks sent. He had deposited all the money he collected to an account with the bank Lincoln Menny Oppenheimer.

The first $1,200 he collected was sent by check on October 10 from Oppenheimer through Lazard Brothers of New York to the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York for them to disburse. A second check of $1,400 was sent to Secretary of State John Hay on November 16. Hanauer sent the final statement in an unofficial letter to Assistant Secretary of State David J. Hill on December 8. He praised the other consuls for their help in the fundraising but also complained about the way he was treated by Lazard Speyer-Ellissen. On the same day, Oppenheimer transferred the final check of $250.89 to Secretary Hay.

Hanauer apparently sent a copy of his final statement to Joseph Sayers, the governor of Texas. Later in December, Hanauer sent another letter to him with a small check and the names of two late contributors. He wanted to make sure that Texas knew where the contributions had come from.

List of Contributors Survives in State Department Records

In total, the effort raised over 12,000 German marks, which was equivalent to about $2,850 at the time. That would be approximately $75,000 in 2016 dollars. Overall, this was quite an accomplishment by Hanauer, for which he was justifiably proud. The number of named contributors was over 180.

The lists of contributors, along with correspondence between Hanauer and the other consulates, have survived for over a century and are now part of Record Group 84, Records of Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. In a box containing estate records from the consulate at Frankfurt is a single envelope containing all of the correspondence Hanauer received about the relief fund as well as his final account to the State Department.

There is a back story to Vice Consul Hanauer’s collection of funds for Texas. On November 6, Charles Vaughn, the deputy consul general at Frankfurt, submitted his resignation to Hanauer, who dutifully reported it to the State Department in a despatch. In early December, the State Department offered Hanauer the position of deputy consul general. He turned down the offer in an official despatch on December 18, stating that he desired to return home with his family within the next year.

Consul General Guenther returned to Frankfurt on December 26 and immediately resumed his position. He must have had a heart-to-heart talk with Hanauer, because on December 28 Guenther sent the State Department a telegram followed by an official despatch informing them that Hanauer had changed his mind.

It is not clear whether Hanauer’s efforts to raise money for Texas convinced his superiors to offer him the position of deputy consul general. Perhaps it was because he had performed his normal duties admirably, or just that he was the next logical choice to fill the position. Regardless, he remained in the post as deputy consul general until 1911.

Postscript

Until the storm struck on September 8, the citizens of Galveston were living in one of the major cities in Texas—an important port and financial center. Over the years, there had been pressure to build a seawall, but public and official opposition prevented it. When the hurricane struck, there was no barrier between the city and the Gulf of Mexico.

The storm remains to this day the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history, with an estimated 8,000 to 12,000 dead after the hurricane destroyed the city. It brought a tidal surge of some 15 feet at a speed as great as 120 miles an hour. Only a few buildings survived and bridges and telegraph lines to the mainland were cut off. Before the storm was done, its effect was felt as far away as Wisconsin and Lake Michigan in the upper Midwest and New York City in the East.

In the aftermath, Galveston rebuilt. The city used dredged sand to raise itself as much as 17 feet above its pre-storm elevation, raising buildings at the same time. But the city never regained its former status as a major center of commerce, especially after a ship channel was built between the Gulf and Houston, making that city a major Gulf port.

Galveston, however, today remains a tourist and entertainment destination as well as a cruise port. Many buildings that survived the storm of 1900 are on the National Registry of Historic Places.

Notes on Sources

The original source of many of the documents is an envelope labeled Record Relief Fund, Texas Flood, 1900. It is contained in a file box labeled Closed Estate Cases, 1901–1902, part of United States Consular Records for Frankfurt am Main, Germany, in Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Record Group (RG) 84, at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

After examination of the entire relief fund file, the author realized that there was some missing information. Additional sources were consulted to augment the information found in the relief fund file. Searching these sources for the time period September to December 1900 revealed additional material used for this article.

Despatches from U.S. Consuls in Frankfort on the Main, Germany, 1829–1906, part of General Records of the Department of State, RG 59, is available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M161. The letters from Hanauer found here included the original newspaper announcements published in Frankfurt newspapers.

Despatches and Reports to the Department of State, 1900–1901 from Frankfurt in RG 84 yielded background about Consul General Guenther’s leave and return, as well as Hanauer’s acceptance of the deputy consul general position.

Letters to Legations, Consuls, etc. (Volume 110) and Letters from Consuls, 1900–1900, (Volume 171) from Frankfurt in RG 84 contained much more of Hanauer's correspondence with the other consuls and the Frankfurt banks about the relief fund.

Additional material from the consulates at Nuremberg and Munich provided some missing information and the list of donors published in the Frankfurt newspaper. Despatch Book Official Letters Sent, 1896–1904 (Volume 140) from Nuremberg and Correspondence, 1899–1901 (Volume 170) from Munich, both in RG 84, yielded the additional documents.

It is quite likely that more corroborating evidence may be found in the records of the remaining consulates that Hanauer contacted. The author searched only those named above. Similarly, there could be other files for Frankfurt that contain some related information. Because the available evidence about the relief fund is fairly complete, a further search was deemed unnecessary.

The names of all contributors that were found in the consulate files, along with the amounts they donated, have been extracted by the author and combined into a single list, which can be made available on request. These names have also been included in a searchable database available on the website of the Mid-Atlantic Germanic Society (www.magsgen.com). On the MAGS Databases tab, search for a name within the Consular Estates record type.

Robert C. Greiner is an experienced genealogical researcher focused primarily on German ancestors. He has transcribed and indexed German church records, published several family histories, and created a web page documenting immigrants from the German Palatinate. Currently he is studying U.S. consulate records from Germany to discover items of genealogical significance. He retired with 43 years of service as a computer systems analyst for the Department of Defense.