JFK 100: Milestones & Mementos

By Stacey Bredhoff

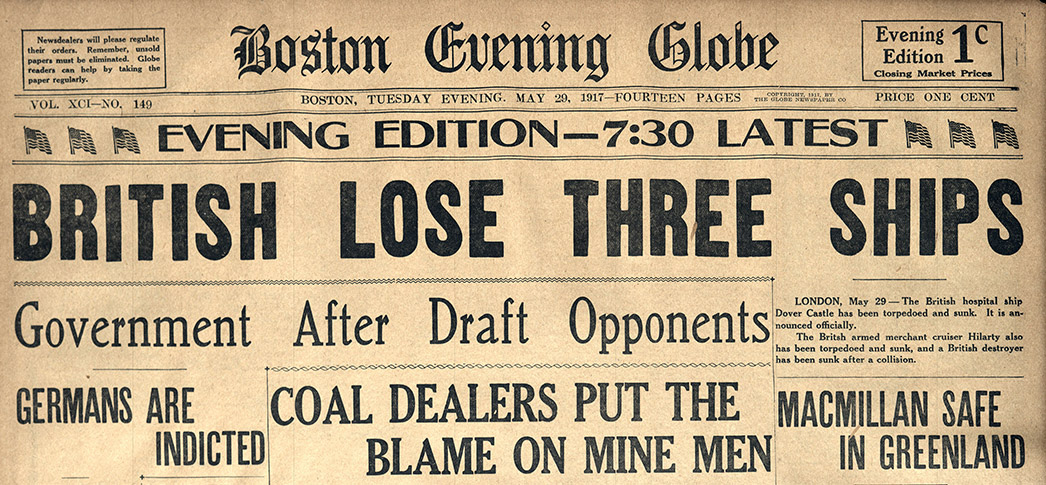

Tuesday, May 29, 1917. News of the Day.

The United States is at war. Aging veterans who had fought in the Civil War now called on a new generation of Americans to perform their duty to safeguard democracy. The front page of the Boston Globe carried their message: “We carried the flag then. You carry it now.” World War I, as the conflict came to be known, would claim the lives of millions of people around the world, including 116,000 U.S. soldiers.

Although American women would not win the right to vote until 1920, the first woman elected to federal office took her seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in April 1917. Jeanette Rankin of Montana made the news again on May 29, 1917, for remarks she made in Congress to galvanize women in the national effort to conserve food. “Every Kitchen Must Be Mobilized,” pronounced the headline inside the Boston Globe.

An episode of mob violence targeting African American men, women, and children in East St. Louis, Illinois, was reported in the New York Times on May 29, 1917. Racial tensions and labor unrest had been building there for months and escalated into a major riot that lasted for days. This event was a precursor to similar explosions of racial violence in many other American cities during the second decade of the 20th century and set the stage for the modern civil rights movement.

As the United States entered World War I, there were just 35 military pilots on its rosters, and the first successful nonstop transatlantic flight by the U.S. military was still two years away. On May 29, 1917, the U.S. Army ran an advertisement in the Boston Globe to recruit student aviators. It was just six years after the U.S. Army had purchased its first airplane, built by the Wright Brothers.

And the Boston Red Sox, reigning world champions, were on their way to Washington, DC, on May 29, 1917, to play a double-header. The team would lose the title in 1917 and win it back in 1918, after which fans would wait 86 long years to celebrate another Red Sox victory in the World Series.

While these topics filled the pages of newspapers on May 29, 1917, another event—whose impact on the 20th century would not be known for many years—took place at 3:00 p.m. in the second-floor bedroom of a family home on a tree-lined street in Brookline, Massachusetts: John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born.

JFK 100—Milestones & Mementos

On May 26, 2017, the Kennedy Library opens a new exhibition, “JFK 100—Milestones and Mementos.” Drawn mostly from the collections of the Kennedy Library, the exhibition celebrates the 100th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s birth with a presentation of 100 items, many of which have never before been displayed.

In the wake of the Second World War—the 20th century’s bloodiest conflagration—during the most perilous days of the Cold War, and amid the rising dangers of the nuclear age, John F. Kennedy lifted the spirits of people around the globe with his courage, his confidence, and the sheer power of his personal magnetism. He gave voice to the nation’s noblest aspirations. His words gave strength to those suffering from oppression, hunger, and despair. And his vision electrified a generation, as untold numbers of citizens answered the call to service that he issued with the now immortal words, “Ask not.”

The 100 items presented in the exhibition provide glimpses of the man, humanizing an elusive historical figure, while bringing his timeless message of hope to a world that still yearns to hear it.

A selection of items from the exhibition is presented here.

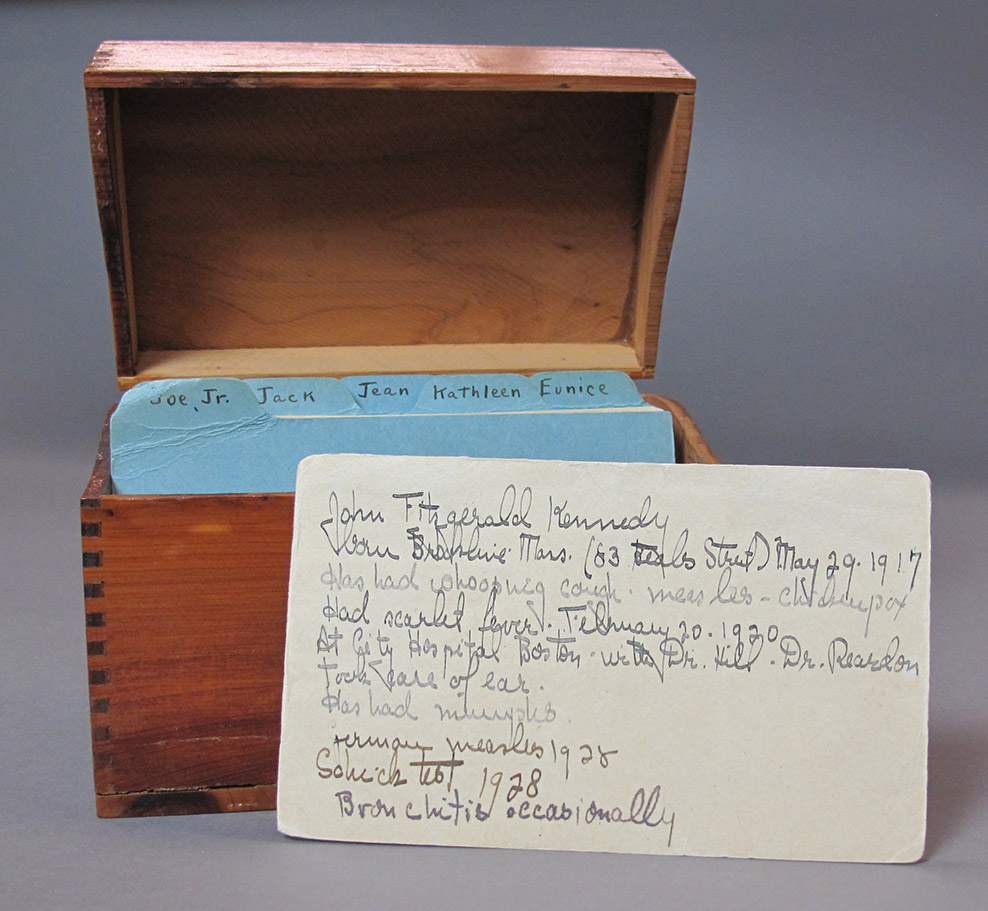

Health records of the Kennedy children, maintained by their mother

John—“Jack,” as he was called by his family and close friends—was the second of nine children born into a close-knit, politically connected Irish Catholic family in Brookline. He had three brothers and five sisters, one of whom was born with an intellectual disability. Politics was in JFK’s blood. Both of his grandfathers—sons of immigrants who came to the United States from Ireland to escape the potato famine in the 1840s—held elective office.

JFK’s mother, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, was the daughter of John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, who served as a U.S. congressman and mayor of Boston. His father, Joseph P. Kennedy, an enormously successful businessman, would come to hold high government posts, including ambassador to Great Britain. Both parents instilled in their children strong values of faith, family, and public service, as well as a thirst for learning and a drive to succeed, making full use of their God-given talents.

The mother of nine, Rose Kennedy devised a card file system to track her children’s health; she bought this cedar box in Brookline to house the records. On this card for Jack she listed whooping cough, measles, chickenpox, scarlet fever, mumps, German measles and bronchitis. On subsequent cards she chronicled an appendectomy, tonsillectomy, and the constant struggle to keep up his weight.

While Jack grew up with every material advantage, he suffered from a series of medical ailments that mystified his doctors and would continue to plague him as an adult. He learned to underplay the effects of his illnesses and, later, to hide the physical suffering he would endure throughout his lifetime.

I purchased a card file from the stationers . . . and recorded all the important information about each of the children. It helped so much to be able to check back on the symptoms of illness, weight, diet and all the important information . . . I would recommend this idea to any mother.

—Rose Kennedy, mother of John F. Kennedy

U.S. flag from PT 109, replaced July 1943, the month before the boat was sunk

JFK’s military service in World War II was a formative experience in his life. He actively sought combat duty and served in the Pacific Theater as commander of a patrol torpedo (PT) boat, PT 109. The mission of the PT boats was to prevent the Japanese ships from supplying their forces in the South Pacific.

In the early morning hours of August 2, 1943, PT 109 was rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer. JFK instantly lost two of his crew and led the survivors through a harrowing ordeal that ended six days later with their rescue. He emerged from the experience a decorated war hero with a battle-tested view of war that would come to shape his perspective as commander-in-chief.

This wind-tattered flag was replaced by a new one shortly before PT 109 was sunk; it is one of the few physical remnants from the boat that still exists.

JFK’s suitcase used during the 1960 Presidential primaries and election

JFK returned home from the war in 1944. Following his physical recovery from back surgery, he decided to pursue a career in politics. A war hero and son of a wealthy and politically well-connected Boston family, Kennedy was elected in 1946 to represent the 11th District of Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress, where he served three terms. By the fall of 1951, he had set his sights on a seat in the U.S. Senate, which he captured in 1952 and then held in the 1958 election. And although he said in a 1957 television interview that “The Senate is the most interesting job in the country,” by 1960 he had reached a different conclusion: “During my years in the Senate,” he said “I have come to understand that the Presidency is the ultimate source of action. The Senate is not.”

Preparing for a Presidential run, he traveled throughout the United States, acquainting himself with the voters and local Democratic Party leaders in every region. Among the challenges he faced as a candidate was an entrenched bias against Catholics and a perception that, at age 42, he was too young and inexperienced for the nation’s highest office. When he made a formal announcement of his candidacy on January 2, 1960, he asserted his qualifications, citing his travels across the country, his 18 years of public service—in the military during World War II and in the Congress—and his international travels. From these experiences, he said, “I have developed an image of America as fulfilling a noble and historic role as the defender of freedom in a time of maximum peril—and of the American people as confident, courageous and persevering. It is with this image that I begin this campaign.”

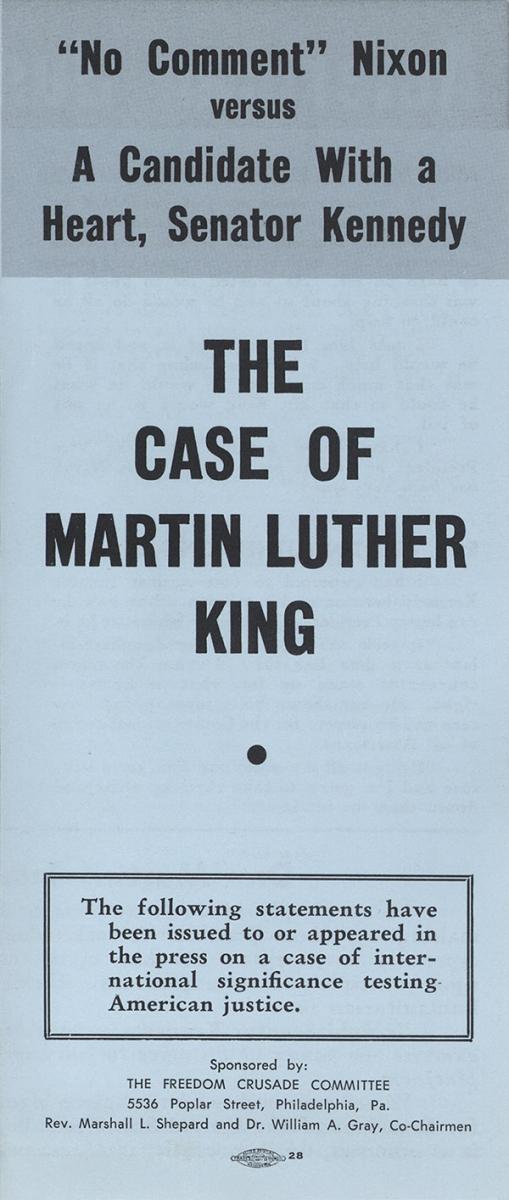

The Case of Martin Luther King, November 1960

Throughout the Presidential campaign, Senator Kennedy carefully steered his campaign between competing factions within the Democratic Party who stood on opposite sides of the debate over civil rights. While he expressed support for redressing racial inequality, he was concerned about losing the support of the southern Democrats who steadfastly opposed the civil rights plank in the party platform. Throughout the campaign, many African Americans remained skeptical about Kennedy’s commitment to civil rights. But as an episode unfolded in the final weeks of the campaign, he won their confidence—and their votes—which proved to be critical in his razor-thin victory.

In the final days of the race, JFK’s campaign printed some 3 million of these pamphlets, publicizing the endorsements of Martin Luther King, Jr.; his father, Martin Luther King, Sr., an influential Baptist minister; and other civil rights activists. (Kennedy and his campaign had expressed support and been instrumental in King’s release following his arrest for taking part in a peaceful protest of a whites-only restaurant in Atlanta, Georgia.) On the Sunday before Election Day, the pamphlets were distributed in African American churches across the country. The pamphlet came to be known as the “blue bomb” for its enormous impact on public opinion. Throughout the episode, the Republican candidate, Vice President Richard Nixon, also contemplated whether to respond and chose to remain silent regarding King’s plight.

On Election Day, Kennedy captured 80 percent of the African American vote, which may have tipped the balance in some critical battleground states.

I am deeply indebted to Senator Kennedy who served as a great force in making my release possible. It took a lot of courage for Senator Kennedy to do this, especially in Georgia . . .

—Martin Luther King, Jr.

I had expected to vote against Senator because of his religion. But now he can be my President, Catholic or whatever he is. It took courage to call my daughter-in-law at a time like this. He has the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right. . . . I’ve got all my votes and I’ve got a suitcase and I’m going to take them up there and dump them in his lap.

—Martin Luther King, Sr.

Department of Defense Briefing Board No. 13, showing the range of nuclear missiles launched from Cuba, February 6, 1963

In the fall of 1962, the Soviet Union, under orders from Premier Nikita Khrushchev, began to secretly deploy a nuclear strike force in Cuba, just 90 miles from the United States, with missiles that could reach many major U.S. cities in less than five minutes. President Kennedy viewed the construction of these missile sites as intolerable, and insisted on their removal. Khrushchev refused—initially. The ensuing standoff nearly caused a nuclear exchange and is remembered in the United States as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On October 28, 1962, as the world’s mightiest military forces stood poised for warfare, Khrushchev relented. In secret negotiations, Kennedy had offered the Soviet premier a way out. The missile sites in Cuba, Khrushchev announced, would be dismantled immediately. The peaceful resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis was one of President Kennedy’s greatest diplomatic achievements.

Three months after the crisis was resolved, the Department of Defense conducted a televised press briefing chronicling the Soviet Union’s buildup and subsequent removal of nuclear weapons from Cuba. This board was used during that briefing to illustrate the gravity of the threat—nearly the entire United States was within range of the missiles.

JFK’s sunglasses, cuff links, tie clip, and tie (Kennedy Library)

In addition to preserving the materials that make up the official record of JFK’s Presidency, the Kennedy Library also preserves many of his personal and family belongings. On the centennial anniversary of his birth, many of these personal items are displayed for the first time, offering a more private glimpse of JFK as a husband and father.

The word “Think” is the design motif of the tie shown here.

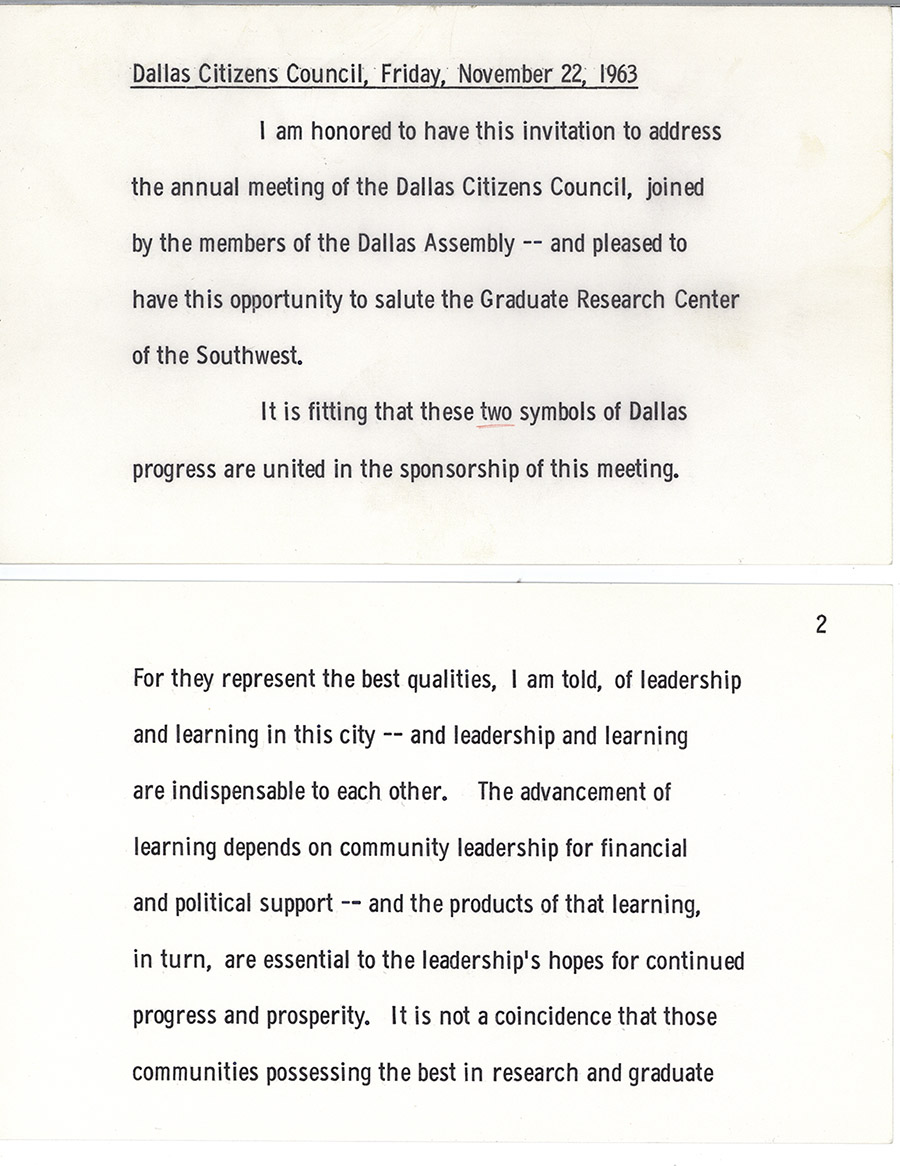

Undelivered remarks for the Dallas Citizens Council, Trade Mart, Dallas, Texas, first two speech cards, November 22, 1963

President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, while riding in an open car, with his wife by his side, during a political trip to Texas. The President’s motorcade had been headed to the Dallas Trade Mart, where he was to deliver these remarks to a crowd of more than 2,000 people—members of the Dallas business community and other local leaders.

JFK came to the presidency with the promise of increasing America’s strength in a perilous world. In this undelivered address prefacing his 1964 campaign for reelection, he recapped the advances the nation had made during his time in office. All 37 of the speech cards are displayed for the first time in the Kennedy Library’s exhibition.

“. . . America today is stronger than ever before. Our adversaries have not abandoned their ambitions—our dangers have not diminished—our vigilance cannot be relaxed. But now we have the military, the scientific and the economic strength to do whatever must be done for the preservation and promotion of freedom.”

—President John F. Kennedy, undelivered remarks prepared for Dallas Citizens Council, November 22, 1963

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, one of the Presidential libraries administered by the National Archives and Records Administration, is in Boston, Massachusetts. You can find out more about the library and its museum and explore its collection online at www.jfklibrary.org.

Stacey Bredhoff, curator of “JFK 100—Milestones and Mementos,” has served as curator at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston since 2008. Prior to that time, she was a senior curator on the exhibits team at the National Archives in Washington, DC.