JFK in Congress

Kennedy Develops Expertise on National Issues as He Prepares to Seek Presidency

Spring 2017, Vol. 49, No. 1

By David McMillen

The year 1946 marked the closing of an era and the beginning of a new world order.

World War II had ended just months before, and cities and towns were crowded with soldiers, sailors, and airmen returning from the European and Asian fronts. The world had witnessed the explosion of two atomic bombs to end the fighting. Rationing would soon end, and plants could turn from the manufacturing of war materials to washing machines, ovens, cars, and—soon—televisions.

Returning veterans were eager to get back to work in civilian jobs and to enjoy a period of peace and security—raise a family, buy a house, go to church, and know that tomorrow would be much like today. The nation, however, was still divided: internationalists vs. isolationists in the Republican party, and southerners vs. northerners in the Democratic party.

Into this world stepped John F. Kennedy, a Navy war hero who stood out among the freshman class in the House of Representatives elected in November 1946. This class also included another former Navy man whose career arc would eventually intersect with Kennedy’s—Richard M. Nixon.

Born in 1917, Kennedy came from a wealthy Boston Irish family that had a long history in politics. His mother’s father had been mayor of Boston and served in the U.S. House of Representatives. His father, following a successful business career, was the first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission before his posting as the American ambassador to the United Kingdom and a brief flirtation with the idea of running for President himself in 1940.

In John Kennedy’s campaign for the House seat from Boston, he voiced views that resonated with a public that had just suffered through a bloody world war. He called for better housing for veterans, better health care for all, and support for organized labor’s campaign for reasonable work hours, a healthy workplace, and the right to organize, bargain, and strike. And he campaigned for peace through the United Nations and strong opposition to the Soviet Union.

JFK Joins Battle Over Taft-Hartley

During his first term in the House, the Senate passed a bipartisan comprehensive housing bill (Taft-Wagner-Ellender Bill) that was blocked by conservatives in the House Banking Committee. Their proposal: a study. Kennedy supported the Senate bill, went to the House floor, and railed against this failure to act. However, as a freshman in the minority and not a member of any of the committees of jurisdiction, there was little else he could do. It would be the end of his second term before Congress finally passed a major housing bill. Even then Kennedy bemoaned that veterans suffered because of Congress’s neglectful delay.

Labor issues also gave Kennedy ample opportunity to stake out his position, although he had little sway over the Republican drafted legislation. Republicans, who controlled Congress, saw this as their opportunity to roll back many of the pro-union provisions that had been adopted during the Roosevelt era. The House passed an anti-union bill early in the 1947–1948 Congress championed by the chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee, Fred Hartley from New Jersey.

Kennedy argued against the Hartley bill, saying that it would make unions impotent in bargaining with management. While acknowledging that there was need for curtailing some union power, he argued that the Hartley bill went too far.

As with housing, Kennedy was more comfortable with the labor bill coming out of the Senate under the leadership of the moderate Ohio Republican, Robert Taft. However, the compromise Taft-Hartley bill went too far. Kennedy opposed it. President Harry S. Truman vetoed the Taft-Hartley bill, but his veto was overwhelmingly overridden.

Shortly after the Taft-Hartley Act became law, Kennedy travelled to McKeesport, Pennsylvania, about 10 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, to debate the merits of the bill. His opponent in the debate was fellow freshman and fellow member of the Education and Labor Committee, Richard Nixon. They shared a meal after the debate and rode together in a berth on the train back to Washington. It is unclear who won the debate, but Nixon won the coin toss for the lower berth.

Kennedy’s Statewide Machine Wins Him a U.S. Senate Seat

By the end of his first term in the House, Kennedy was already looking toward the Senate. However, he was not yet ready for a statewide race.

Following his reelection to the House, he set a goal of speaking in every city and town in Massachusetts. Today, members of Congress travel to their home district nearly every weekend; however, that was not the case in 1948. Then, members traveled home only once every four to six weeks. Kennedy was the exception. He would leave Washington every Thursday evening and spend the next three days at any political event to which he could secure an invitation.

Any political club, fraternal organization, veterans group, or business association that was looking for a speaker was on his list. As a congressman and war hero, he was welcome everywhere. While these speaking events gave Kennedy wider name recognition and the opportunity to meet people face to face, Kennedy also began compiling a list of names of individuals who could be tapped for campaign work in the future.

That future began arriving in 1952. Kennedy ran for the Senate seat held by Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., and won.

Kennedy’s victory over Lodge was neither a sure thing nor an easy one. Lodge was first elected to the Senate in 1936 and took a leave of absence to serve in World War II. When, in 1944, the secretary of war barred members of Congress from active duty, Lodge resigned his Senate seat to serve.

Lodge, too, was a war hero, just as Kennedy became when he rescued his crew after the Japanese destroyed his PT-109 in the Pacific. Fighting in Europe, Lodge single-handedly captured a four-man German patrol. Both men received high military honors.

After the war, Lodge, a well-known moderate Republican, returned to Massachusetts and was reelected to the Senate in 1946. In 1952 Lodge spearheaded the effort to persuade Dwight D. Eisenhower to run for the presidency and, following a hard-fought convention battle against Taft, became Eisenhower’s campaign manager.

Not surprisingly, Kennedy’s Senate campaign got off to a slow start. It was his first statewide election, and he was still a relative newcomer to politics. However, before long, the Kennedy campaign began to take advantage of those thousands of names and contacts Kennedy had collected in his four-year barnstorming of the state. The women in the Kennedy family, his sisters and cousins, hosted teas across the state. Shaw reports that “about 75,000 women” attended the Kennedy teas.

The Eisenhower campaign, however, may have been Lodge’s undoing. By the time he turned his attention to his own campaign, Kennedy had a substantial campaign machine in operation. Kennedy won the election with 51.5 percent of the vote.

(Elections with a Kennedy facing a Lodge have not been unusual in Massachusetts. In 1916, Lodge Sr. defeated Kennedy’s grandfather for the same Senate seat, and in 1962 Edward Kennedy defeated Lodge’s son George for the seat’s unexpired term vacated when John Kennedy was elected President.)

Kennedy in the Senate: Now a National Figure

Politically, the 1950s are defined by the Eisenhower/Nixon administration. Kennedy’s defeat of Lodge came in the midst of a Republican landslide. In 1952, Eisenhower captured 55 percent of the popular vote and 81 percent of the Electoral College. The Republicans took control of the House with a 42-seat swing. The Senate was more closely divided with 48 Republicans, 47 Democrats, and 1 Independent; however, nine deaths and one resignation during the 1953–1954 Congress resulted in control of the Senate shifting from Republican to Democrat to Republican again.

The 1950s are often characterized as an idyllic time. Television shows like Leave it to Beaver and Father Knows Best showed family harmony and a time of little stress. Eisenhower governed as a modern Republican in contrast to the frenzied pace of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In fact, the 1950s was a period of rapid social change.

The baby boom encompassed the entire decade, and rapid population growth spurred economic demand. Housing adopted the automobile’s mass production techniques, which made homes affordable and made the suburbs possible. Families were more mobile, thanks to the automobile, the interstate highway system, the rise of fast food restaurants, and motel chains to serve those exploring America by car.

This rapid transformation of the social background was accompanied by an equally rapid transformation in Kennedy. He had progressed quickly during his six years in the House. He developed a potent campaign machine and defeated a popular incumbent. Now in the Senate, he set his sights on expanding his political skills and his attention to foreign affairs.

Kennedy’s first committee assignments in the Senate were the Labor and Public Welfare Committee and the Government Operations Committee. His office was on the third floor of the Russell Senate Office Building, at the time the only Senate office building. Across the hall was the office of the President of the Senate, Vice President Richard Nixon.

Breaking with New Englanders Over St. Lawrence Seaway

In late spring 1953, Kennedy gave three speeches on the Senate floor outlining his New England economic plan—a plan he argued was good for both New England and the nation. Kennedy argued for a diversified economic base for New England with job training and technical assistance for the workers and relief from harmful tax provisions for the firms. He called for increasing the minimum wage and stronger enforcement of the child labor laws.

Kennedy argued that his economic plan would also strengthen the country’s fight against communism. Federal and state programs that supported workers both on the job and when unemployed would challenge some of the allure of the communist program pitched to the unemployed and the poorly paid workers.

Fellow senators from New England and beyond, the press, and even the White House praised the young senator for addressing real problems and offering concrete solutions.

Kennedy distinguished himself again as a national figure in the debate and vote on building the St. Lawrence Seaway. Congress had discussed the seaway for more than 30 years without action, but in the 1953–1954 Congress it appeared that would change. In the first term, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee approved a bill authorizing American participation in the construction of the seaway. The House Public Works Committee held hearings on the seaway but did not report a bill.

As a member of the House, Kennedy, like all members of the New England delegation, opposed the seaway. Conventional wisdom was that the seaway would harm both the Port of Boston and the entire New England economy. Now in the Senate, he took a broader perspective.

At the beginning of the second session of the 1953–1954 Congress, Kennedy announced his support for the seaway. It will be built, he argued, and thus the only question is whether it was better for the United States to participate in the construction and administration of the seaway. Both national security and the national economy would benefit from U.S. participation. The seaway was authorized later that year with Kennedy voting in support of the bill. No Massachusetts senator or representative had ever supported the seaway project.

Kennedy’s vote was criticized in the New England press, but he was praised nationally for his willingness to put the interests of the country above parochial concerns. Kennedy positioned himself as a national statesman.

A Chance to Burnish A Scholarly Reputation

Kennedy was also making his mark as the scholar senator. Kennedy’s Harvard senior thesis had been published in 1940 as Why England Slept and quickly became a bestseller. In 1956, he published Profiles in Courage, which spent months on the New York Times bestseller list and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1957. His reputation as a scholar led Vice President Nixon to appoint Kennedy chair of a committee to select the five most outstanding senators to appear in a Senate Hall of Fame. The chairmanship was destined to produce considerable publicity, and his name also appeared each week on the bestseller list.

Now Kennedy’s name began to appear on lists of potential running mates for Adlai Stevenson to challenge the Eisenhower/Nixon ticket in the 1956 election.

Kennedy was a star at the August 1956 Democratic convention. He narrated the introductory film about the Democratic Party, The Pursuit of Happiness. Stevenson asked Kennedy to place his name in nomination. Kennedy responded with a glowing defense of Stevenson and the party and a tough critique of the Eisenhower/Nixon record.

Turning Point in 1956: A Loss Becomes a Win

Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee was the favorite for the vice-presidential nomination, which Stevenson threw open to the convention. Kefauver had led a special committee investigation into organized crime that was one of the first televised Senate hearings, and the publicity made him a well-known name. Despite Kefauver’s advantage, Kennedy made a strong showing at the convention. No candidate was selected on the first ballot, and Kennedy had the lead on the second ballot, but not enough votes to secure the nomination. When Kefauver ultimately won the nomination, Kennedy called on the convention to make the nomination unanimous. Even in defeat, his star rose.

Kennedy campaigned relentlessly for the Stevenson/Kefauver ticket. According to John T. Shaw in JFK in the Senate: Pathway to the Presidency, Kennedy traveled more than 30,000 miles, gave more than 150 speeches, and covered 24 states in the weeks leading up to the election. Stevenson and Kefauver lost the election, and by Thanksgiving, Kennedy had decided to run for President.

Kennedy negotiated the Senate Hall of Fame committee with political skill. What could have been a minefield with everyone pushing their own agenda turned into unanimous support for the committee’s selections. Kennedy established rigorous evaluation criteria, consulted with noted historians, and recognized both the context of the Senate and the times in which the senators served. The five senators honored were Henry Clay of Kentucky (Whig 1831–1842, 1849–1852), Daniel Webster of Massachusetts (Whig, 1827–1841, 1845–1850), John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (Democrat, 1832–1843, 1845–1850), Robert M. LaFollette, Sr., of Wisconsin (Republican, 1906–1925), and Robert Taft of Ohio (Republican, 1939–1953).

While planning a run for the presidency, Kennedy made good use of his time in the Senate.

He used his position on the Senate Labor Committee to push for an increase in the minimum wage and to protect union rights in an environment where Congress was trying to strip unions of any power to bargain effectively.

Kennedy joined the Foreign Relations Committee in 1957. There he supported Algerian independence from France and sponsored an amendment that would provide aid to Russian satellite nations. Kennedy also introduced an amendment to the National Defense Education Act to eliminate the requirement that aid recipients sign a loyalty oath and provide supporting affidavits. Service on the Foreign Relations committee strengthened candidate Kennedy’s international credentials.

The McClellan Committee Gets a National TV Audience

Kennedy’s role on the McClellan Committee, chaired by Arkansas Democrat John McClellan, also bolstered his credentials as a candidate. The McClellan Committee was established in 1957 to investigate labor management relations in the postwar environment of organized labor. When the time came to write legislation, the committee turned to Kennedy, who drafted and managed the labor bill through the Senate and managed the conference committee with the House.

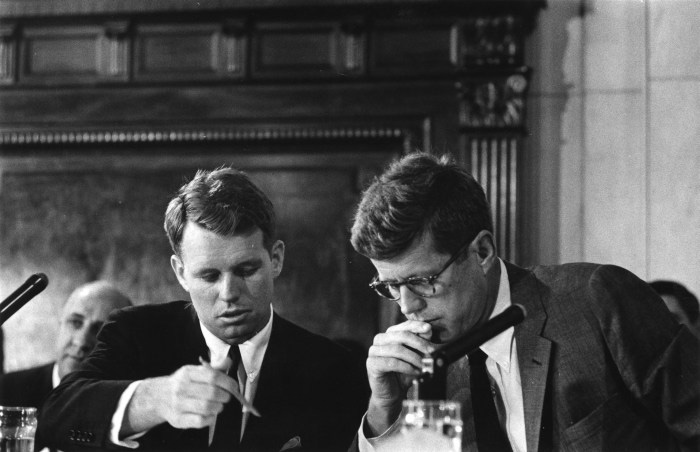

The formal title of the committee was the Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management. McClellan had been investigating organized labor through his subcommittee in the Government Operations Committee. The unions objected, arguing that the appropriate place for such investigations was in the Senate Labor Committee, where Kennedy chaired the Labor Subcommittee. McClellan resisted transferring jurisdiction because he feared Kennedy was too pro-union. To resolve this jurisdictional conflict, the Senate created the Select Committee; Robert Kennedy, the senator’s brother, was selected as chief counsel.

The growth of television in the 1950s changed the political landscape in Congress. The broadcast of the McClellan Committee hearings provided an opportunity for senators to be seen by voters across the country. Kennedy took full advantage of the hearings to be seen as a fair and intelligent senator. Earlier in the decade, gavel-to-gavel telecasts of the Army-McCarthy hearings were a significant factor in the decline of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin Republican who had been riding an anticommunist wave since the beginning of the decade.

Corruption in the Teamsters Union was a continuing focus of the select committee. After repeatedly invoking the Fifth Amendment before the committee, Dave Beck was forced out as president of the union. That led to repeated clashes between Kennedy and James Hoffa, who succeeded Beck. While the committee repeatedly uncovered evidence of corruption in the Teamsters Union, it was unsuccessful in removing Hoffa. However, Hoffa’s reputation was tarnished enough that the Teamsters were expelled from the AFL-CIO.

When it came time to draft legislation based on the findings of the McClellan Committee investigation, the committee turned to Kennedy. He consulted widely with political and legal experts, held 15 hearings, and worked with his Republican counterpart, Senator Irving Ives of New York, to craft the bill. The Kennedy-Ives bill contained a number of provisions to constrain both management and union activity. The bill passed the Senate 88 to 1; however, the House refused to act on it before Congress adjourned. Early in his career, Kennedy had gone to the House floor to scold his colleagues for failing to act on economic reform. He took to the Senate floor to do the same when the House failed to act on the Kennedy-Ives bill.

Ives retired at the end of the 1957–1958 Congress, and Kennedy, reelected easily in 1958, turned to fellow Democrat Sam Ervin from North Carolina for support. The Kennedy-Ervin bill passed the Senate early in the 1959–1960 Congress with added provisions to garner stronger support from labor. The House responded by passing a strong anti-labor bill, and Kennedy presided over the House-Senate conference to resolve the differences.

Kennedy saw the compromise bill as deeply flawed because it contained too many of the anti-union provisions from the House; however, it was the only bill possible. Despite the disappointing content of the bill, Kennedy won high praise from several of his Senate colleagues for his command of the subject matter and his political skills in managing the bill to conclusion.

On January 2, 1960, Kennedy announced his candidacy for President of the United States. From that point forward, he was no longer Senator Kennedy but Candidate Kennedy, and he rarely attended committee hearings or Senate votes.

He put together a careful plan for winning the nomination and in the process defeated more experienced politicians like Hubert Humphrey, Stuart Symington, and Lyndon Johnson. He then built a skillful general election campaign for the presidency, defeating his freshman colleague, Richard Nixon.

Note on Sources

For information about John F. Kennedy during his years in the Senate, one of the best sources is John T. Shaw’s book JFK in the Senate: Pathway to the Presidency, published by St Martin’s Press in 2013.

In addition, the John F. Kennedy Library has a detailed report of Kennedy’s voting record in the House and Senate at www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/JFK-Fast-Facts/Voting-Record-and-Stands-on-Issues.aspx.

A more general look at the social and political climate during this period is available in David Halberstam’s book The Fifties, published in 1993 by Villard Books.

A detailed study of the presidential campaign in 1959 and 1960 is available in Theodore White’s book The Making of the President, 1960 (Cambridge, MA: Atheneum Publishers, 1961).