Confederate Slave Payrolls Shed Light on Lives of 19th-Century African American Families

By Victoria Macchi | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, March 4, 2020 — For all of March 1862, a man named Ben cooked for the Confederate military stationed at Pinners Point, VA, earning 60 cents a day that would go to his owner.

A few months later and 65 miles away, Godfrey, Willis, and Anthony worked on “obstructions of the Appomattox River” at Fort Clifton.

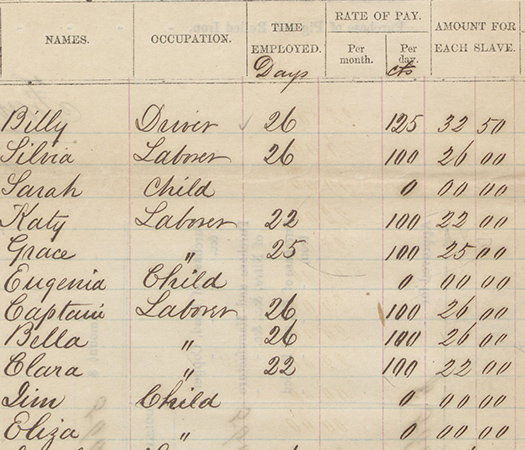

Then there were Grace, Silvia, and Bella, among several women listed as laborers at South Carolina’s Ashley Ferry Nitre Works in April 1864, near the names of children like Sarah, Eugenia and Sampson.

They are single lines, often with no last name, on paper yellowed but legible after 155 years, among thousands scrawled in loping letters that make up nearly 6,000 Confederate Slave Payroll records, a trove of Civil War documents digitized for the first time by National Archives staff in a multiyear project that concluded in January.

For years, the Confederate Army required owners to loan their slaves to the military. From Virginia to Florida, the enslaved conscripts were forced to dig trenches and work at ordnance factories and arsenals, mine potassium nitrate to create gunpowder, or shore up forts.

The Confederate Quartermaster Department created the payrolls for slave labor on Confederate military defenses. After the end of the Civil War, the Federal War Records Office arranged, indexed, and numbered the documents.

Although the sums listed beside each name on the payroll would go to their owner, and not the slave who performed the labor, the documents provide a rare record of slave names.

“Their names were not on the census records,” explains Claire Kluskens, an archivist who led the project and worked for years to digitize the payrolls. There are church records, and probate documents, but “otherwise, this would be one of the few lists of slaves owned by a slave owner,” she added.

Although some states have additional slave payrolls, the National Archives maintains thousands of documents captured during the war from 10 southern states; most are from Virginia and North Carolina.

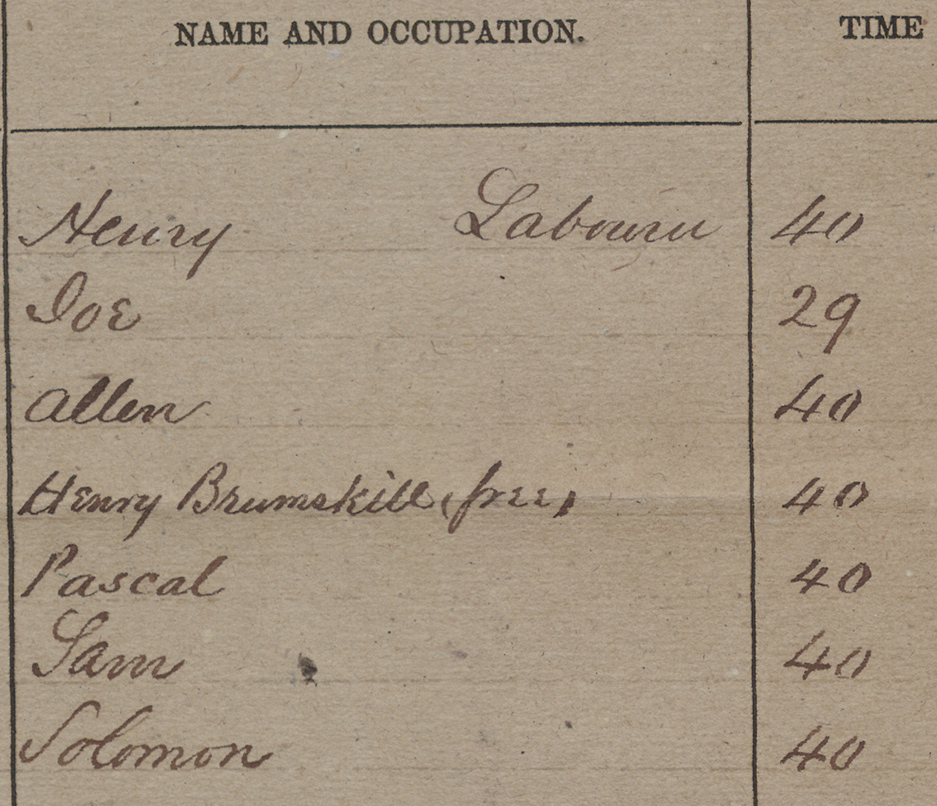

The rolls show the period covered, the entity or person that employed the slaves working for the Confederacy, the place of service, the name of owner, the name and occupation of the hired enslaved person, the time employed, rate of wages, amount paid, and the signature of the person receiving the money (usually the owner or an attorney).

There are rare finds among the documents, like Henry Brumskill, a free black man (Slave Payroll 848), “runaway” slaves (Slave Payroll 3831), and white employees (Slave Payroll 490).

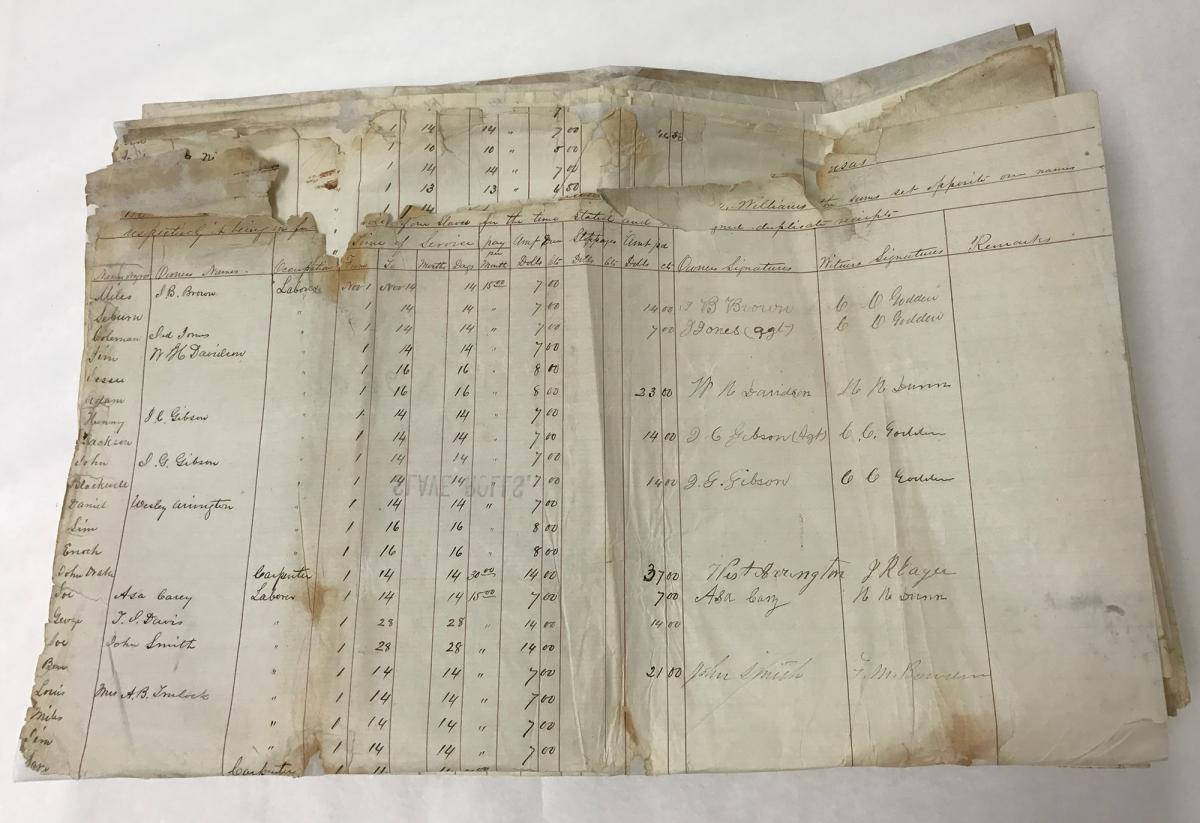

Before the documents could be scanned, the National Archives conservation team had to stabilize them. There were tears and breaks that could render some text illegible.

The goal wasn’t to make each page look perfect; it was to safely get them onto the scanner, with as much of the original information available as possible—including attachments that had to be untied or unglued—and processed in the right order. For these records, that took a little over 3,000 hours.

"To see it now, it's like 'oh this looks great! It doesn't really need much,'" says Halaina Demba, a conservator who worked on the payrolls project. "But these would have been crumpled, these pieces would have probably been falling off, it's really embrittled in a lot of these areas," she says, handling a sheet with browned creases.

The lists—which in some cases, were part of a document that rolled out to 13 feet long—may interest African American genealogists, local historians, and researchers on slavery during the war.

“I really got a lot of appreciation for them because I have friends on the public history side who are using these records for their public programs,” says Rachel Bartgis, a conservation technician who also worked to prepare the slave payrolls for digitization. “It was really only after the records were digitized and they went online that I had the opportunity to actually sit down and think [about them].”

View the entire collection of Confederate slave payrolls in the National Archives online catalog.