The Spies Behind Lincoln’s ‘Secret War to Save a Nation’

By Jonathan Marker | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, August 8, 2019 — The world’s “second oldest profession,” as it is known in the parlance of spycraft, found a home in both the Union and the Confederacy in the bloody years of the Civil War. Begun in earnest with the Battle of Fort Sumter on April 12-13, 1861, and ended with Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, the Civil War is famous for having pitted brother against brother in mortal combat.

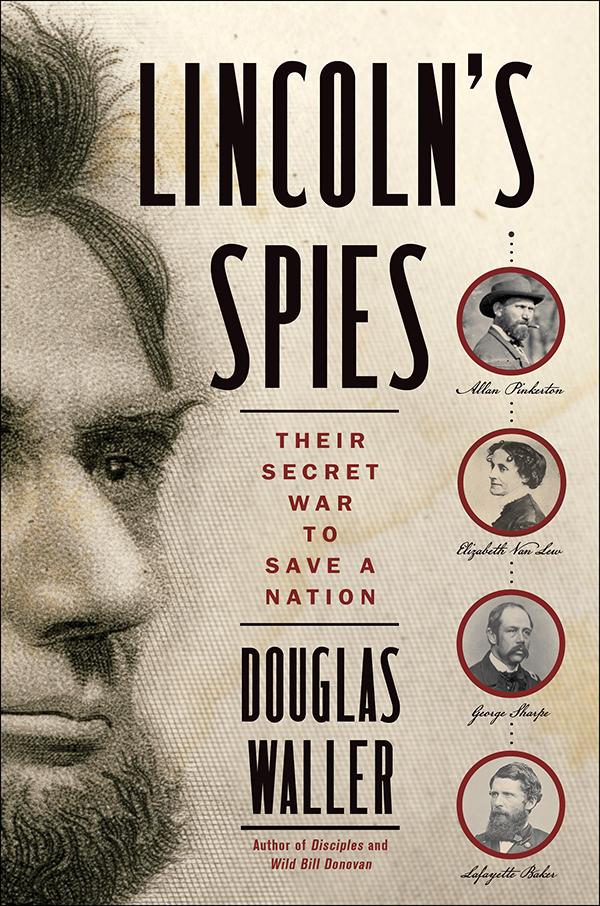

According to Douglas Waller, author of Lincoln’s Spies: Their Secret War to Save a Nation, secrets written with quill and ink served as much purpose in the Civil War as musket and cannon. At a public program at the National Archives in Washington, DC, Waller discussed the “secret battles” undertaken by Union agents, focusing on four individuals from among the countless operatives whose cloak-and-dagger exploits yielded vital information to President Abraham Lincoln: Allan Pinkerton, Lafayette Baker, George Sharpe, and Elizabeth Van Lew.

Waller spent “countless hours” performing research at the National Archives. He thanked Trevor Plante, Chief of the Reference Services Branch, for his help, jesting, “I don’t think [Plante] could get from one part of the building to the other without me tackling him at some point, begging him for information.”

Since many of the commanding officers in both the Union Army and Confederate Army shared a formal education through West Point before the Civil War, accurate and timely intelligence provided a battlefield advantage in spite of the opposing side knowing every tactic. In his book, Waller chose to focus on Union spies. “I found Union operatives to be far more interesting than their Confederate counterparts,” he said. “Two of my spies were heroes in this war, one was a failure, and the other was a scoundrel, so I had a pretty good mix of characters here to deal with.”

Allen Pinkerton, Waller said, was a famous private detective who “honed a sixth sense to anticipate criminal activity before it happened.” In February 1861, Pinkerton won Lincoln’s favor when he uncovered evidence that Secessionists wanted to assassinate the new president-elect at a stopover in Baltimore to keep him from being inaugurated in Washington. However, Pinkerton’s overestimation of Confederate Army strength caused him to fall out of favor as General George McClellan’s spymaster, and Pinkerton was succeeded by George Sharpe.

Sharpe was a highly successful spymaster for the Union Army of the Potomac. His background gave him many advantages: he hailed from a privileged family in Kingston, NY; graduated from Rutgers University with honors; earned a law degree from Yale University; and, after opening a practice as an attorney, went on to serve with distinction as a Union Army officer. Sharpe’s fluency in French caught the attention of General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker, who summoned Sharpe to translate a book written on France’s secret service. On its quick return from Sharpe, Hooker then appointed him as head of the Bureau of Military Information, a Union espionage agency Waller called “decades ahead of its time.” Using what is now called all-source intelligence, Sharpe synthesized highly accurate intelligence reports on Confederate military capabilities for Union military commanders.

Contrasting with Pinkerton and Sharpe’s more traditional modus operandi was Lafayette Baker, a Union officer and staunch opponent of Pinkerton. Waller described Baker as someone who was “as devious and manipulating as his idol, Eugene Francois Vito, an unsavory detective who helped create France’s secret police force.” Baker found employment in Washington, DC prior to the Civil War when he convinced General Winfield Scott, commander of the Union Army, to give him a job as a secret service agent. In this capacity, Baker employed seedy characters from the underbelly of DC in his cadre of spies. Baker’s greatest failure, Waller said, was his inability to uncover the assassination plot led by John Wilkes Booth.

Countering the long-held notion that the Civil War was only a man’s fight, Waller portrayed Elizabeth Van Lew as a domestic spymaster who ran a sizable cadre of agents from her own home in the heart of the Confederacy. A highly intelligent heiress from Richmond, VA, Van Lew developed an early empathy for slaves she saw being beaten in the streets of her hometown. After being sent to relatives in Philadelphia to continue her studies, Waller said, “[Van Lew] returned to Richmond with an even fiercer hatred of human bondage.” She used her sizable fortune, inherited from her father upon his death in 1843, to free slaves and help them flee to the North. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Van Lew tended to Union soldiers imprisoned in Richmond, convinced Confederate authorities to bring the prisoners meals and books, and provided medical care. Her affection for the Union cause made her an outcast in Richmond society, but in the face of continual accusations of treason by Confederate officials, Van Lew persisted in getting critical intelligence to Union forces.

Countering the long-held notion that the Civil War was only a man’s fight, Waller portrayed Elizabeth Van Lew as a domestic spymaster who ran a sizable cadre of agents from her own home in the heart of the Confederacy. A highly intelligent heiress from Richmond, VA, Van Lew developed an early empathy for slaves she saw being beaten in the streets of her hometown. After being sent to relatives in Philadelphia to continue her studies, Waller said, “[Van Lew] returned to Richmond with an even fiercer hatred of human bondage.” She used her sizable fortune, inherited from her father upon his death in 1843, to free slaves and help them flee to the North. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Van Lew tended to Union soldiers imprisoned in Richmond, convinced Confederate authorities to bring the prisoners meals and books, and provided medical care. Her affection for the Union cause made her an outcast in Richmond society, but in the face of continual accusations of treason by Confederate officials, Van Lew persisted in getting critical intelligence to Union forces.

To find out more about some of the unsung heroines of American history, visit the Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote exhibit in the Lawrence F. O'Brien Gallery, on display through Sunday, January 3, 2021.

The recorded program is available on NARA’s YouTube channel.

The talk continued NARA’s summer series of noontime programs, which are free and open to the public in the William G. McGowan Theater of the National Archives Museum in Washington, DC. Attendees are encouraged to use the Special Events entrance on Constitution Avenue at 7th Street, NW. The museum is Metro-accessible on the Yellow and Green lines, from the Archives/Navy Memorial/Penn Quarter station. Reservations are recommended and can be made online. For those without reservations, seating is on a first-come, first-served basis. The Theater doors will open 45 minutes before the start of the program. Late seating will not be permitted 20 minutes after the program begins.

Visit this link to view a calendar of upcoming events across the National Archives.