NHPRC News - September 2014

NHPRC News — September 2014

Inside the Commission

NHPRC and Social Media

In addition to reading about NHPRC news and grant opportunities in this newsletter, you can also follow us on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/nhprc; on Twitter at #NHPRC, and through our Annotation blog at http://blogs.archives.gov/nhprc/ -- for all the latest news, grant information, and webinar announcements.

Grant Deadlines

-

Archives Leadership Institute

For a project to continue the Archives Leadership Institute.

Final Deadline: December 4, 2014

-

Digital Dissemination of Archival Collections

For projects to make historical records of national significance to the United States broadly available by disseminating digital surrogates on the Internet.

Final Deadline: December 4, 2014

-

Literacy and Engagement with Historical Records

For projects to explore ways to improve digital literacy and encourage citizen engagement with historical records.

Final Deadline: December 4, 2014

-

Publishing Historical Records in Documentary Editions

For projects to publish documentary editions of historical records of national significance.

This program has two deadlines:

Final Deadline: (for new projects) December 4, 2014

-

State Government Electronic Records

For projects to accession, describe, preserve, and provide access to state government electronic records of enduring value.

Final Deadline: December 4, 2014

Online Tutorial for Preserving Family Archives

The North Carolina State Historical Records Advisory Board (SHRAB) in collaboration with the State Archives of North Carolina has produced a series of tutorials that provide basic information about the care and handling of family papers. These tutorials were funded by a grant from the NHPRC. The complete series is available on YouTube and selected tutorials are also available in the Preservation section of the State Archives website.

The five videos provide information on:

- Identifying and Protecting Essential Family Records

- General Paper Preservation Tips

- Caring for and Sharing Family and Personal Papers

- The Care and Preservation of Family Photographs

- Managing and Preserving Digital Images

In FY 2015, the NHPRC will be funding a new grant program—Literacy and Engagement with Historical Records—to help archives with projects like the North Carolina SHRAB series, designed to improve digital literacy and encourage citizen engagement with historical records. The grant program offers support for projects that will result in archives reaching audiences through digital literacy programs and workshops, new tools and applications, and citizen engagement in archival processes.

The NHPRC is looking to fund pilot projects in areas that:

- Develop partnerships among archives, historical records repositories, educational, and community-based institutions to provide educational opportunities for people, particularly students, to develop their digital literacy skills when they find, evaluate, and use primary source documents online. In addition, projects may seek to increase individual understanding of technology operations and concepts so that they can engage in effective personal digital archiving or other types of digital archives curriculum development.

- Create or develop new online tools and applications, including mobile apps, to enhance public understanding and access to historical records.

- Enlist "citizen archivists" in projects to accelerate digitization and online public access to historical records. This may include, but is not limited to, improving crowdsourcing efforts for identifying, tagging, transcribing, annotating, or otherwise enhancing digitized historical records.

The NHPRC is looking for projects to experiment with new techniques and methods in these three areas that will provide models for other organizations and that people and institutions can adopt for free. Deputy Executive Director Lucy Barber will host a webinar for interested applicants on Thursday, September 11 at 3:00 pm Eastern at https://connect16.uc.att.com/gsa1/meet/?ExEventID=86503625.

Saving Arizona

Our partnership with state historical records advisory boards often lead to breakthrough projects at the local community level. A two-year grant to the Arizona Historical Records Advisory Board (AHRAB) will enable the Board to assist in implementing funding priorities and key recommendations in its long range plan, facilitate cooperation among historical records repositories and other information agencies within the state, and promote a leadership role for the Board in the historical records community in Arizona. It also provides funding for special projects.

Several AHRAB members and colleagues from Northern Arizona University, Arizona State University, the Arizona Historical Society and the University of Arizona participated in the 2014 Arizona Archives Summit held earlier this year, attended by 65 people from archives throughout the state, including representatives from the Hopi Cultural Preservation office, the Hualapai Tribe's Department of Cultural resources, the Office of the Navajo Nation and the Colorado River Indian Tribes Library and Archives. This year the SHRAB invited representatives from four, small repositories in under-served communities to talk about the challenges they face and the solutions they have developed to help them cope with under-funding, poor storage for archival collections, volunteer based staff and more.

And the SHRAB reported on activities at four re-grant projects, including the Casa Grande Valley Historical Society, which used its grant to prepare its very first Finding Aid. With regrant funds, the CGVHS was able to provide basic access to the Jim Gorraiz Photographic Collection which contains images of Casa Grande and the surrounding region, landscapes, family portraits, and other photographs documenting this small community south of Phoenix. You can access the Finding Aid on their website.

First Person Archivist: Appalachian State University

Trevor McKenzie, Project Archivist for the W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, Appalachian State University Special Collections, shares with us the story of his first job as an archivist:

When I came to work as the Project Archives Assistant on the NHPRC grant at Appalachian State in the Fall of 2012, my only prior experience working in the archives was limited to a few months as a student. My interests lie primarily in absorbing knowledge concerned with the history and folklore of the Appalachian Region through music, literature, arts, material culture, and—perhaps most useful of all— conversations and word of mouth. This desire to understand the history local to the region drew me to attend Appalachian State in 2007. The deciding factor in my choice of university was the existence of the W. L. Eury Appalachian Collection, the largest and most comprehensive collection of Appalachian materials anywhere in the world.

To say I was “a kid in a candy store” when wandering around in the collection would be putting it lightly. Within the open stacks I could find materials on anything from archaeological surveys of ancient Indian Mounds to records of Kentucky fiddler Marion Sumner to a video on Virginia architectural influences in southern Ohio. As if that was not enough, just on the other side of the wall in the Dougherty Reading Room I could view documents from the ballad collections of I. G. Greer, W. Amos Abrams, and Cratis Williams or read the letters of E. B. Olmsted, a ginseng buyer in 19th Century western North Carolina. After spending time in the Eury Collection, I was determined that, if I could not eventually work there, I would at least try to work towards finding a job in a similar collection somewhere within the region.

The NHPRC grant to process the backlog within the Appalachian Collection’s archives coincided with my graduation with a degree in Appalachian Studies in 2012. I applied for the University Library Specialist knowing I would have much to learn concerned with archival practices but I was excited at the prospect of handling and helping to preserve historic documents as part of a daily routine. In processing the backlog I determined to balance my previous experience as a researcher with the practical constraints and time limitations of the grant. I began each collection by asking the same key question: How can I arrange these materials in a relatively short amount of time while still making it easy for researchers to find the items they need? Tackling many of the larger collections within the backlog, I learned that each collection features a particular set of quirks dissimilar to others. To work out how to best process a collection I found that a hammer/anvil approach—hammer being the processing guidelines and anvil being the shape of the collection itself—is needed in order to address the problems within each collection. My supervisor and the grant writer for this project, Cyndi Harbeson, was a constant sounding board for my concerns and questions regarding how best to process or reprocess a collection and helped me in balancing processing times with creating researcher friendly collections. Fellow Processing Archives Assistant Anita Elliot also picked up the slack for me in helping with processing grant materials, including knocking out a large number of the small collections as well as offering advice from her own experiences in processing.

Aside from the practical duties of processing, working on the grant introduced me to materials which reignited my enthusiasm for Appalachian history. Some of my favorite finds (as well as other eye catching items) are included on the Backlog Blog which I will continue to update until November when the grant is completed. Perhaps the most invaluable experience from the grant (along with the obvious benefits of exclusive access to rare documents) was that it allowed me to work in close contact with a Special Collections team whose members possess both scholarly and personal knowledge of the Appalachia’s landscape and culture. I am indebted to the jumpstart the NHPRC has given to my career and I hope to continue to use the knowledge I have gained through this grant to preserve and explore more collections valuable to the study of the history of this region and its people.

St. Alban’s Raid

On October 19, 1864, the northernmost land action of the American Civil War took place in the tiny town of St. Albans, Vermont, when a small group of Confederate soldiers entered the country from Canada, intending to rob banks and cause the Union Army to divert troops to defend the northern border. During the raid, Confederates held the villagers at gun point on the village green, taking their horses to prevent pursuit. Several armed villagers tried to resist, and one was killed and another wounded.

The raiders escaped to Canada, and in response to U.S. demands, Canadian authorities arrested the raiders, recovering $88,000. However, a Canadian court ruled that because they were soldiers under military orders, officially neutral Canada could not extradite them. Canada freed the raiders, but returned to St. Albans the money they had found.

While working on an NHPRC-supported project to arrange and describe court records from three northern Vermont counties, archivist Susan Swasta came across a nondescript envelope in a box of miscellaneous papers. It contained a set of case files which had been removed from their original locations.

Swasta identified them as court records related to St. Albans Raid, including the inquest of the sole bystander killed during the raid, as well as documents related to the capture, transport, incarceration, and trial of suspected raider Hezekiah Payne. One witness testified against Payne, saying, "I saw this man … fire twice with his pistols."

The town of St. Albans is commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Raid with special events on September 18-21, and you can read more about the events, including two accounts of the role of historical records at http://www.stalbansraid.com/.

Courtesy North Carolina State Archives.

Courtesy North Carolina State Archives.

The Casa Grande Valley Historical Society.

The Casa Grande Valley Historical Society.

Archivist Trevor McKenzie

Archivist Trevor McKenzie

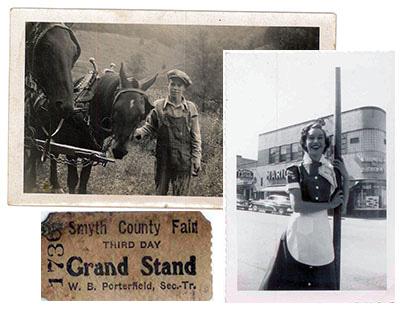

Photo collage from the Smyth County collection, Eury Special Collection.

Photo collage from the Smyth County collection, Eury Special Collection.