Jefferson Buys Louisiana Territory, and the Nation Moves Westward

Spring 2003, Vol. 35, No. 1

By Wayne T. De Cesar and Susan Page

Two centuries ago this spring—without a call to arms, with little advance notice, and with only the briefest negotiations—the United States doubled in size.

In an astounding transaction that amounted to four cents an acre, President Thomas Jefferson saw his dreams of westward expansion coming true for the nation he had helped create.

The United States of America would grow beyond the Mississippi River and include the rich forests, vast plains, and craggy mountains that would one day yield the vital resources to make it the most powerful and most prosperous nation on earth.

The historic transaction is known as the Louisiana Purchase, but it was not something that Jefferson had sought to make at the time. He would have been content just to buy the port of New Orleans so the United States—not Spain, not France, certainly not Great Britain—could control the gateway to the Mississippi River, the main street of commerce in what was then the American West.

But France's ruler at the time, Napoleon Bonaparte, was losing interest in establishing a North American empire and needed funds to fight the British, so he directed his emissaries to offer not just New Orleans but all of the Louisiana Territory to the Americans. Jefferson's envoys in Paris, without awaiting any direction from their President (which would have taken two months), accepted the deal and on April 30, 1803, signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

The story of the Louisiana Purchase, however, is more than just a quick deal among the top French and American diplomats in April of 1803. And it took more to complete the Louisiana Purchase than the treaty itself.

It involved more than a year's worth of delicate negotiations to work out the approval of the treaty by Congress, the raising of funds to finance the purchase, and the transfer of documents that completed the deal. There were agreements on how the deal would be financed and various delegations of powers of attorney to individuals carrying out the various functions—some thirty documents in all.

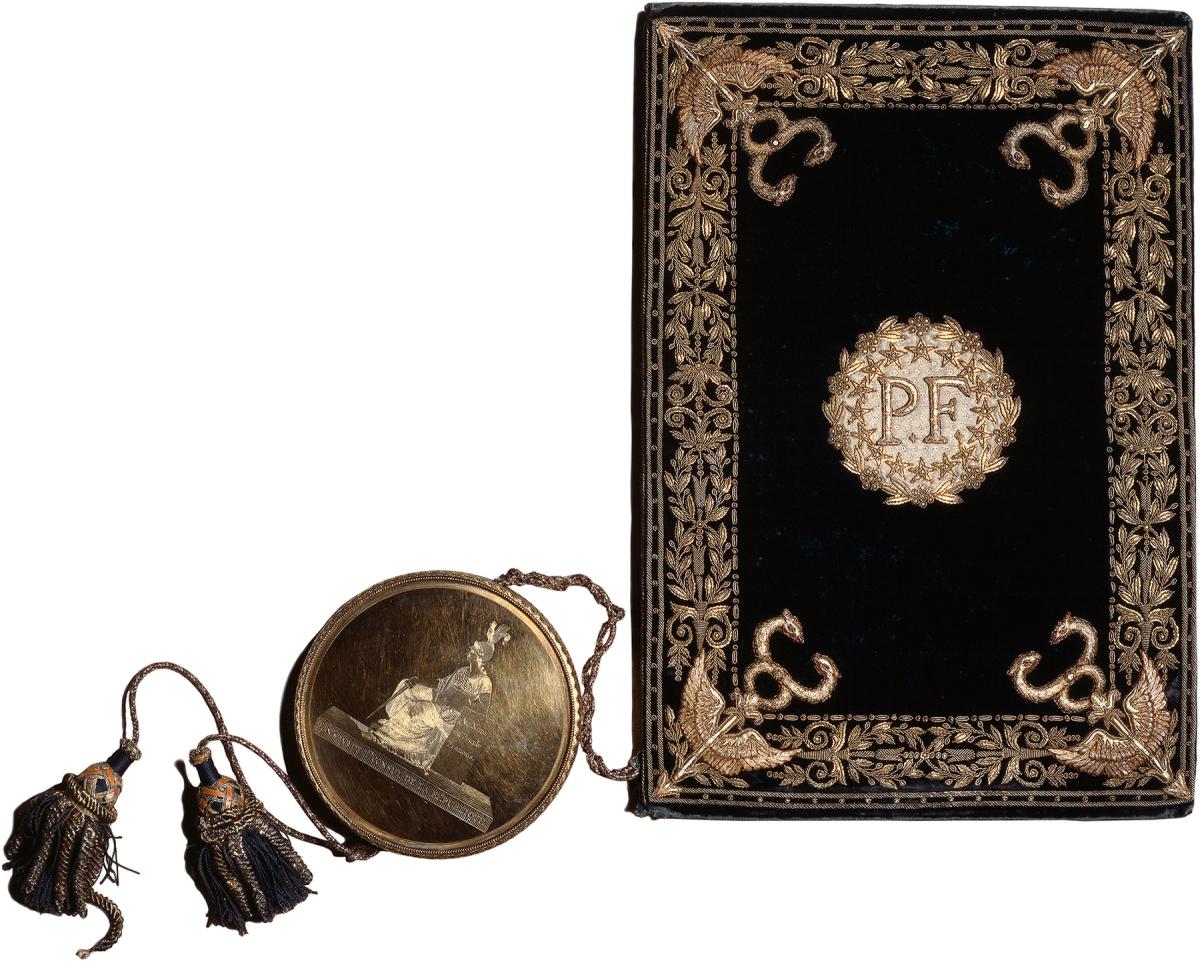

Over the years, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty and the two side conventions, which stipulated how France would be compensated for Louisiana, have been part of Department of State records held by the National Archives. They have also been part of NARA's popular "American Originals" exhibit, which is now touring various cities around the country. The treaty shows Napoleon's signature as well as other noted French and American historical figures, such as James Monroe, who later became President, and Talleyrand, Napoleon's foreign minister.

Thirty other documents that were needed to implement the Louisiana Purchase also exist, and for many years were kept at the Department of the Treasury. At one point in the 1930s, they were sent to the National Archives for lamination and returned to the Treasury Department. In 1951 they were accessioned by the National Archives and in 2000 underwent significant conservation work in the NARA Document Conservation Laboratory in College Park, Maryland, in preparation for the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase this year.

The Original Goal: Buying New Orleans

The Louisiana Purchase was as quick in the making as it was historic in its impact.

Jefferson's men were in Paris because he wanted to buy the port of New Orleans. To him, New Orleans was key: Whoever owned it would be America's natural enemy because that nation would control the channel through which produce from more than a third of the United States had to pass.

Even as he was laying the groundwork for what became the Lewis and Clark Expedition, to explore Louisiana and the western lands, Jefferson gave his ambassador in Paris, Robert Livingston, instructions to negotiate with the French to buy New Orleans.

France had ceded Louisiana to Spain in 1762 in the Treaty of Fountainebleau. But in 1800–1801, France took it back under the terms of the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 and the Convention of Aranjuez in 1801.

However, at war with England, France kept the retrocession a secret. Napoleon feared that if England knew Louisiana was once again French, it would attack Louisiana with its superior fleet and take possession. He had planned a future colonial empire in North America and the West Indies in which Louisiana would provide raw materials for the sugar islands, an outlet for French goods, and a territory for settlement.

Spain, meanwhile, had built fortresses along the eastern edge of the Mississippi, angering western Americans by infringing on what they thought was their natural right of navigation to the sea. To calm the Americans, Spain agreed to the right of Americans to deposit their goods for reshipment at New Orleans in the Treaty of San Lorenzo in 1795.

But by 1802, Spain had not lived up to its obligations, twice refusing rights of deposit at New Orleans and not providing another site as stipulated in the 1795 treaty. Western Americans were at a fever pitch and ready to sail down the Mississippi and take New Orleans by force.

To avoid a possible armed insurrection and an unpleasant international situation, Jefferson embarked on a plan. While Spain was solely responsible for the fiasco, France was deemed the actual cause of the insufferable actions. Jefferson now appointed fellow Virginian Monroe as minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to join Livingston in Paris. Monroe was to work with Livingston on negotiations with France to purchase for ten million dollars the Isle of Orleans, on which New Orleans was located, and "the Floridas," which ran along the coast from present-day Florida to Louisiana and were thought to be French possessions. Napoleon now welcomed negotiations with the Americans. His plans for an empire in America and the West Indies had by this time vanished. A slave revolt and yellow fever ended his plan to subjugate Santo Domingo. Moreover, he feared war with England again and wanted money for the fight.

A Surprise Offer and a Time Crunch

On April 11, 1803, a day before Monroe arrived in Paris, the French minister of foreign relations, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, surprised Livingston by offering the United States not just New Orleans but all of the Louisiana Territory. François Barbé-Marbois, the French minister of the public treasury, discussed the possible sale of Louisiana again with Livingston on April 13.

Although the newly arrived Monroe was less inclined to exceed his instructions, he went along with the idea as an agreement was reached. For four days at the end of April 1803, the Americans and the French worked out an agreement, and on April 30 a treaty was signed. To spell out how the fifteen-million-dollar compensation for Louisiana would be paid, the negotiators also signed two "conventions."

The first convention, signed by Livingston, Monroe, and Barbé-Marbois, detailed how the United States would pay the $11,250,000 (sixty million francs) in stock with an interest rate of 6 percent and not redeemable for fifteen years.

The second convention detailed how the United States would assume the claims of American citizens against the French navy for seizure of property and goods from American ships at sea. The amount was put at $3,750,000, with 6-percent interest as well, but payments were not to begin until sixty days after the exchange of ratifications, which took place on October 21, 1803.

Jefferson did not learn about the historic deal until July 3, and did not receive the official documents until July 14. There was little opposition at home. The Spanish, however, objected, saying France did not have clear title and had promised never to sell Louisiana to a third party. But Spain's protest did not have French support, and Secretary of State James Madison produced a letter from Spain's foreign minister saying, in effect, that the United States could buy anything it wanted from France as a result of the retrocession.

Jefferson also worried about the constitutionality of the acquisition, for the Constitution did not specifically grant the federal government the authority to acquire more territory, and he considered an amendment to the Constitution.

But Napoleon was becoming impatient and threatened to void the treaty. Speed was now essential to complete the deal. Jefferson went along with his advisers and dropped the idea of a constitutional amendment and pushed for ratification by the October 30 deadline. The Senate did so on October 20 by a vote of twenty-four to seven. The next day in Washington, the Americans and the French envoy exchanged ratified copies of the treaty.

By November 3, therefore, both houses of Congress had passed legislation authorizing the President to take possession of Louisiana and to create stock for its purchase from France.

Many More Documents Implemented the Treaty

Now the real work of implementing the treaty and the two conventions began. Because of a possible war with England, French banks would neither buy nor market the American stock. So Livingston and Monroe suggested that two firms, Baring and Company of London and Hope and Company of Amsterdam, conduct the sale of the stock.

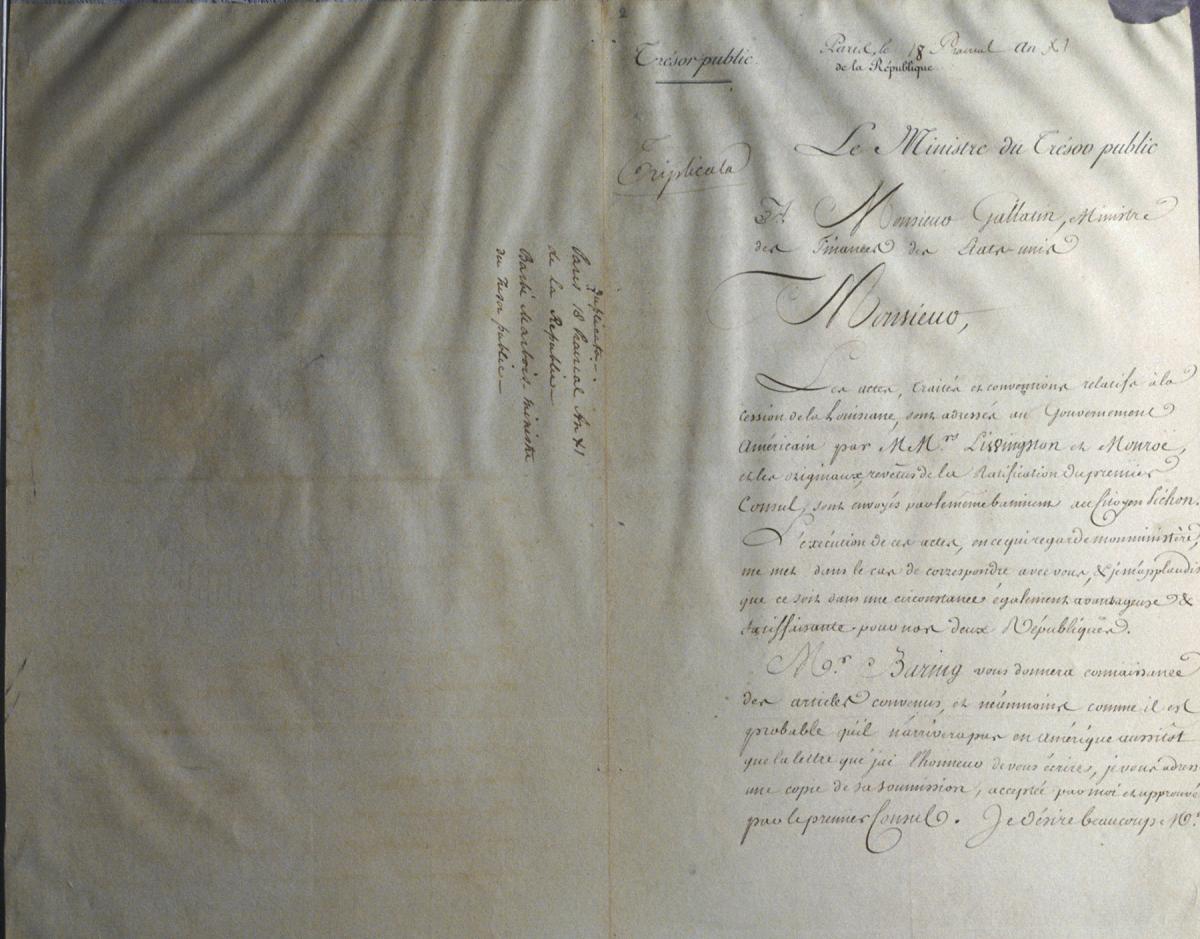

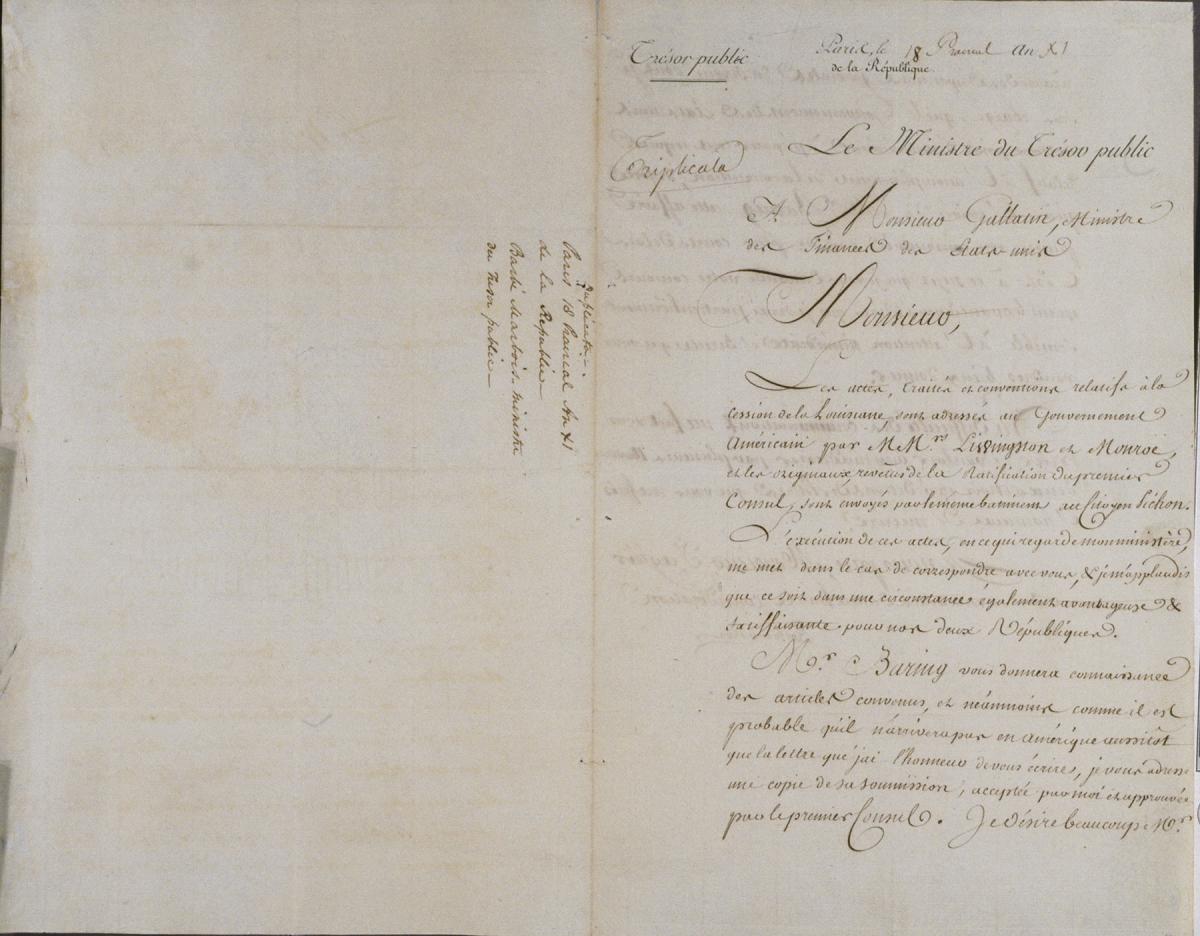

Hoping the suggestion would be viewed favorably, between May 3 and May 5, 1803, Alexander Baring of Baring and Company was given powers of attorney by both companies for entering into negotiations with France and the United States. On May 28, Barbé-Marbois and the American ministers exchanged correspondence relating to what was now called the American Fund. France approved the suggestion and signed a contract with Baring and Company and Hope and Company for the negotiation of the American Fund, witnessed by Livingston and Monroe, on June 6. On the same day, Barbé-Marbois wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin that Baring would be arriving in America to begin the transfer of stock.

In the United States, Baring was granted more detailed powers of attorney by Hope and Company on July 20 and Baring and Company on August 12 as to the American Fund. He was now able to negotiate the number and amounts of certificates to be transferred, to whom the certificates would be made, and the place at which interest would be paid, among other points. The actual fiscal details fell into place, and the $11,250,000 became more than a figure.

The challenge, then, was getting the stock to Europe.

On December 1, Baring asked Gallatin for the stock to be issued, with receipts ($3,750,000 for Baring and $7,500,000 for Midshipman John B. Nicholson to be delivered to Lt. James Leonard for delivery to Livingston in Paris; Livingston would give a receipt to Leonard upon receiving the stock).

Gallatin wrote a note to Jefferson asking for the date possession was taken of New Orleans so that the register of the Treasury, Joseph Nourse, could fill in the date on the stocks from which interest was to be calculated. Jefferson replied on the bottom of the note that the date was December 20 and sent it back to Gallatin. Gallatin and Baring agreed that the funds would be paid yearly in four installments, and Jefferson approved. A warrant for the preparation of stock certificates for $11,250,000 at 6-percent interest was sent by Gallatin to Nourse, stating that the certificates were not to be issued without further orders from Gallatin.

On January 16, 1804, Jefferson sent a warrant to Gallatin to issue the certificates, and the same day Gallatin sent a warrant to Nourse to deliver certificates for $3,750,000 to Baring and another $7,500,000 in certificates to be delivered to Livingston in Paris. Also on the same day, Baring requested Nourse to transmit two-thirds of the stock (the $7,500,000) to Livingston. Somewhere along the line, plans changed as Gallatin then instructed Nourse to deliver the stock to be sent to Livingston into the hands of Jefferson's private secretary, Lewis Harvie, who would act as messenger and sail from Norfolk. Nourse drafted a letter to the French chargé d'affaires, L. A. Pichon, and Baring, requesting instructions as to the delivery of the stock to Livingston. Pichon wrote to Gallatin the same day agreeing to the transmission arrangements.

On February 7, however, Gallatin informed Nourse that they were back to the original plan: The stock was now to be delivered to Midshipman Nicholson to deliver to Lieutenant Leonard, who would sail from New York. The delivery was made and documented on February 13 by a receipt from Leonard to Nicholson. Livingston acknowledged the delivery of the stock to him in Paris by issuing a receipt to Leonard. On April 28, Barbé-Marbois issued a quitclaim to Hope and Company, relinquishing France's claim to the territory.

To complete the transaction, in a letter to Gallatin from Bordeaux, France, Leonard enclosed a duplicate original receipt from Livingston for the stock Leonard delivered to him. Nourse received a letter from Edward Jones, clerk for Gallatin, in which was enclosed the original receipt from Livingston for the stock delivered by Leonard to him in Paris.

The Story Just Begins for Historic Documents

In December 1803, the Louisiana Territory officially became part of the United States. But the story was not over for the documents of the Louisiana Purchase. It was just beginning.

The Louisiana Purchase treaty and the two conventions, both the French and English versions, which were part of the records of the Department of State, were accessioned by the National Archives in 1938. Since then, these documents have been exhibited at the National Archives or loaned to other institutions for exhibition and have undergone minor conservation work—chiefly repairs—from time to time.

Over the years, the thirty implementing documents, in the custody of the Treasury Department, survived extensive handling, excessive exhibition, and uncontrolled storage environments before they came to the National Archives in 1951 for good.

But they made at least one visit to the Archives in the 1930s—to be laminated, then a new technique. The National Archives began laminating records (using hydraulic presses to apply cellulose acetate film) in 1936, and the Louisiana Purchase records, treated in the late 1930s, were among the earliest records to be laminated. The last lamination press was removed in the late 1980s, and documents are no longer treated by cellulose acetate lamination.

At the time of its dominant use, however, cellulose acetate lamination was a state-of-the-art preservation technique, used to protect precious and inherently valuable historic documents—providing a means of supporting and holding together fragile or fragmented paper. Because it is generally soluble in acetone, cellulose acetate lamination can be a reversible process if materials on the laminated document are not affected by the acetone.

The thirty laminated Louisiana Purchase documents represented a wide range of types and conditions. Some documents were very simple as physical objects, such as a single sheet of cream colored paper written in brown iron gall ink on both sides. Others were more complex: for example, a large piece of watermarked antique laid paper with hand stamps, resin seals and important signatures. Some were distorted, yellowed, and embrittled. Others, however, appeared to be in good condition; they were flat, supple and written on paper that was no more significantly darkened than similar but unlaminated paper two hundred years old.

While it is impossible to know how each document was treated over the years, some plausible explanations for their varying conditions exist. They may have been laminated using excessive heat and pressure, the cellulose acetate may have contained unstable plasticizers, or they may have been overexposed to light during long-term exhibition at the Treasury Department. Resin seals on some documents remain intact, while others have been crushed, which indicates that some documents were carefully laminated by hand to protect vulnerable resin seals, hand stamps and presidential signatures that they bore, while others were not.

In most cases, cellulose acetate lamination is reversible in acetone, a common organic solvent. It generally does not harm the paper, inks, hand stamps, or seals, though careful testing prior to any treatment is necessary to verify the safety of the solvents needed for delamination. Cellulose acetate lamination fell from favor and was replaced by polyester encapsulation, introduced in 1976 at the Library of Congress and at the National Archives in the early 1980s. Encapsulation involves placing a document between two sheets of polyester film, all of whose edges are sealed except for air holes at the corners; encapsulated records can be easily removed from their protective enclosures by cutting off the sealed edges of the polyester envelope.

Delaminating Documents Required Tests, Careful Procedures

The delamination of the Louisiana Purchase implementing documents at the Archives did not begin until a half-century after they were accessioned from the Treasury Department in 1951.

In 2000, a condition report and treatment proposal for the records described each document and its physical appearance: type of paper, media, any special features such as seals, stamps, and notations. Each document's condition was also assessed and described, including location of major and minor tears, breaks or losses, presence of stains, areas of discoloration, as well as the location of any previous repairs.

Three documents were chosen for initial conservation treatment to represent a specific conservation issue or problem of varying complexity. Results of the tests would help determine the treatment for other documents. The three documents were:

- "Letter from the Minister of the Public Treasury of the French Republic to the Secretary concerning the arrival of Alexander Baring in America and the plans for carrying out the terms of the agreement" (original in French). This is a double-sided single page document of cream colored antique laid paper bearing the Dutch "Cobb & Co" watermark and written in iron gall ink. Like many other Louisiana Purchase documents, it had a strip of cotton gauze adhered to its left edge, with gauze strips that were sewn together and bound into a book. There were some smudges and tears, but the paper was in generally good condition.

- "Convention between the French Republic and the United States." This document was selected to represent records that had been on permanent exhibit. This item, pages 1 and 2, also represented a higher degree of challenge because the document, written on strong antique laid paper, had become very badly distorted during exhibition and it was at first unclear whether these planar distortions could be reduced or eliminated during treatment. Tape had been applied to the verso to hold the record in position in its window mat during exhibition. In addition, the ink on the document had previously bled as a result of contact with water.

- "Power of attorney given to Alexander Baring by Hope and Company to act in American matters relating to the negotiations of the American fund" (July 20, 1803). This document in the pilot project was selected for treatment because it, like several others, had a fragile red resin seal. The seal was attached to the verso near signatures and hand stamps in black ink. This document represented the highest degree of conservation challenge in the pilot project.

Before any conservation treatment began, testing was done to determine whether the inks were soluble in the solvent selected for delamination. Fortunately, each document had a wide left border of cellulose acetate that extended beyond the paper itself, to allow it to be bound into a volume. A long strip of cotton gauze had been attached to the left edge of the paper document before it was laminated. This non-record salvage strip was removed and used to test the solubility of the cellulose acetate.

After several attempts to dissolve the lamination in acetone, the conservator tried a mixture of acetone and water; the lamination quickly dissolved. The delaminated cotton gauze was removed from the beaker, dried, and examined. After delamination, the previously yellowed appearance was gone. The gauze appeared white, clean and, when the solvents and water had completely evaporated, the fabric was flat.

Next, all inks, seals, hand stamps, and all other media were tested for solubility with the acetone and water mixture to determine that all materials were safe and would not bleed when immersed in the mixture during delamination. The treatment proceeded following a step-by-step protocol. Each document was immersed in a tray containing acetone and water until all the cellulose acetate had been removed. This delamination process usually required several baths, sometimes as many as seven immersions.

Next, the documents were bathed in a mixture of ethyl alcohol and water containing calcium. Calcium has been shown to stabilize both the iron gall ink and paper. Adding alcohol to the water reduces the risk of solubilizing the ink present. After bathing in water and ethyl alcohol, the documents were briefly immersed in calcium-enriched water alone.

Following bathing, the paper was dried between blotters with special protection and cushioning to protect seals and paper wafers during drying. Tears, losses, and fragile or vulnerable areas behind the seals or thick areas of highly acidic and corrosive iron gall ink were mended and reinforced with Japanese handmade paper adhered with wheat starch paste.

Some of the seals had been crushed during lamination and were consolidated with an adhesive applied with a very fine brush, with work being conducted under high magnification using a binocular microscope. Each document was encapsulated in a strong, stable transparent polyester film.

Upon initial examination, many of the Louisiana Purchase documents appeared to be in relatively poor condition. But after delamination, the documents were brighter in appearance, the ink contrast was greatly enhanced, and the integrity of the paper had been preserved.

All thirty of the implementing documents were delaminated by October 2000. In 2002, three blank stock certificates, which were used to raise funds for the purchase, were discovered among the records of the Bureau of the Public Debt, a Treasury Department agency. They are awaiting minor preservation treatment but will require only humidification, flattening, and very minor mending.

Following conservation treatment, several of these implementing documents were placed on short-term exhibit under low light levels as part of the National Archives' "American Originals" exhibition, which has also featured the treaty and the conventions. The National Archives has also loaned some of the documents to exhibit during Louisiana Purchase bicentennial observances (see accompanying list).

An Unusual Ceremony Provides a Historic Moment

The Louisiana Purchase is considered one of the great chapters in American history—when Jefferson's men seized the moment and, in a single action, changed America and its place in the world.

On December 20, 1803, in an unusual ceremony in New Orleans, the flag of Spain was lowered, the flag of France was raised and then lowered, and the flag of the United States was raised, signifying the two changes in ownership of Louisiana—828,000 square miles often called the greatest real estate deal in history.

With the purchase of Louisiana, Thomas Jefferson's long-held dream of westward expansion took a giant leap. His plan to explore it and discover its riches and possibilities was already under way. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark would write the next chapter.

Wayne T. De Cesar is a reference archivist with the National Archives and Records Administration, Textual Services Division, where he works with the Treasury/Revenue/Finance cluster of Federal records. He joined NARA in 1989 as a member of the Records Declassification Division, and a few years later worked for a year with the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff.

Susan Page is a senior paper conservator and member of the Document Conservation Branch. She joined the NARA staff in 1987 after working at the Library of Congress since 1979.