Cold Mountain's Inman: Fact Versus Fiction

Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2

By Richard W. Peuser and Trevor K. Plante

Author Charles Frazier has turned a Civil War tale of a Confederate soldier into a best-selling book and blockbuster movie, Cold Mountain. The protagonist of the story is a man named Inman, who served with the Confederate army during the Civil War.

The story begins with Inman deserting from a hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he was recovering from a neck wound he received at Petersburg, Virginia. The tale then revolves around Inman's journey home to Cold Mountain, in western North Carolina, to reunite with his love, Ada Monroe. Before reaching home, Inman is gunned down by local home guards.

Was there a real Inman? If so, do records exist in the National Archives that relate to him and his possible service in the Civil War?

The answer to the first question is yes, there was a person named Inman. In the last line of the book's acknowledgments, the author apologizes for the "great liberties" taken with W. P. Inman's life. The author based the book on the Civil War service of William P. Inman, Twenty-fifth North Carolina Infantry Regiment. The answer to the second question would have been more difficult to answer if it had not been for the remarkable efforts of a former War Department adjutant general, Fred C. Ainsworth.

Ainsworth headed the office that created the compiled military service records for soldiers who served in Union and Confederate volunteer organizations. During the period 1886–1912, the War Department, specifically the Record and Pension Office, a unit in the Adjutant General's Office, created more than six million cards for Confederate army volunteers.

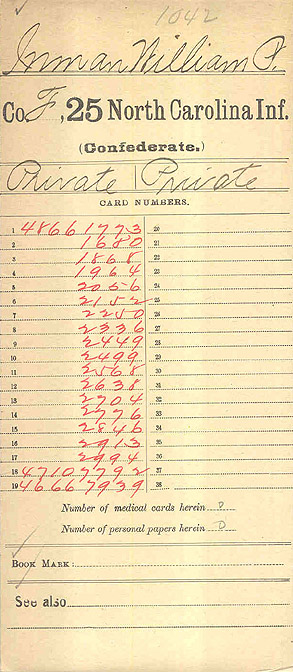

Compiled military service records are essentially records transcribed from other sources. Information from company muster rolls, regimental returns, descriptive books, hospital rolls, prison records, and other records was copied verbatim onto cards. A separate card was prepared each time an individual name appeared on a document. Therefore, instead of searching for William P. Inman's name through fragile, unwieldy documents such as returns, muster rolls, hospital registers, etc., a researcher can find information on him in a compiled military service record.

Interestingly, Frazier reveals in one of his interviews that he was able to get information on Inman's Civil War service through the North Carolina State Archives. All of the Confederate compiled military service records were reproduced on National Archives microfilm many years ago, and microfilm copies are available at various southern state archives and patriotic, civic, and historical associations.

In Record Group 109, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, there is a compiled military service record for a Pvt. William P. Inman who served in Company F, Twenty-fifth North Carolina Infantry Regiment. The first card provides some personal information. His physical description is listed as five feet, seven inches tall with dark hair and a fair complexion. Inman, from Haywood County, North Carolina, was twenty-two years old at the time of his enlistment. He enrolled for duty with Capt. Thomas I. Lenoir's Company of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina State Troops in Haywood County on June 29, 1861. The unit mustered into state service on July 20. Later, Lenoir's company was changed to Company F of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina Infantry Regiment and entered into Confederate service on October 22, 1861, at Camp Davis, near Wilmington, North Carolina.

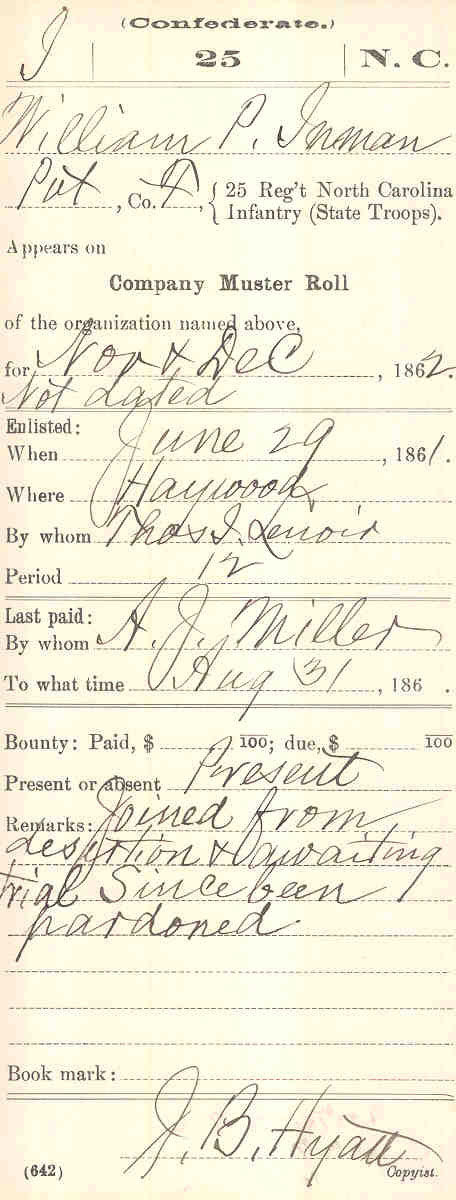

Inman's service record shows that he was wounded July 1, 1862, at the Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia, a major engagement that ended the Seven Days Campaign and Union Gen. George B. McClellan's attempt to take Richmond. Inman deserted on September 5, 1862, twelve days before his regiment saw action at the Battle of Antietam, Maryland. Inman returned to his company on November 19, 1862. The records state that he was pardoned for this offense. The service record reveals that he was present for the remainder of the year, was with the Twenty-fifth North Carolina when it saw action at Fredericksburg, Virginia (December 1862), and was with his unit for all of 1863.

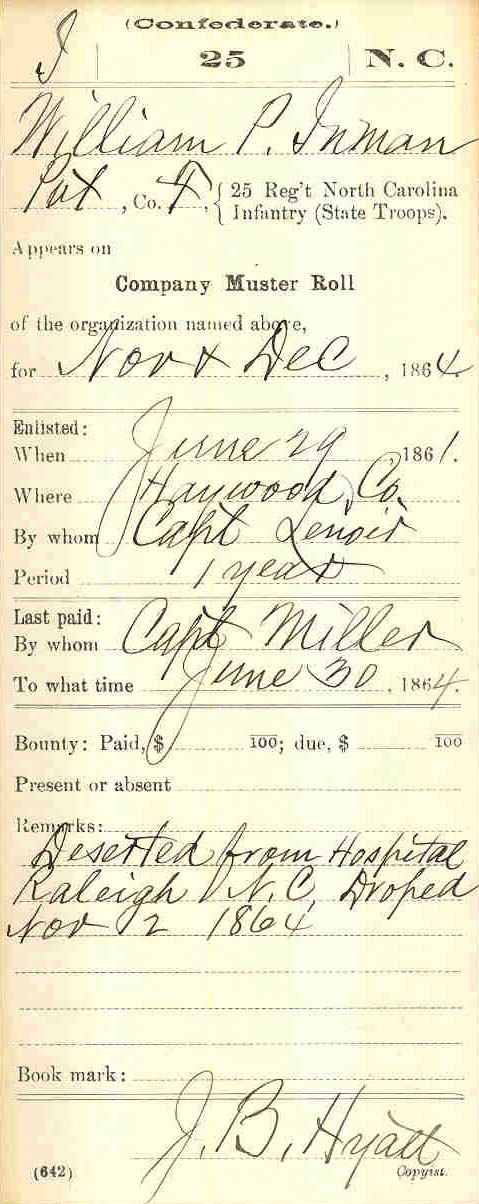

During the summer of 1864, the Twenty-fifth North Carolina participated in the siege of Petersburg, Virginia (June 1864–April 1865). Part of that action, known as the "Battle of the Crater" (July 30, 1864), is where the movie Cold Mountain begins. It was at the Crater that W. P. Inman was wounded. His compiled military service record reveals that he was admitted to a general hospital in Petersburg, Virginia, on August 21, 1864, due to a gunshot wound to the neck. He was later transferred to hospitals in Danville, Virginia, and Raleigh, North Carolina. On October 11, 1864, he was discharged from the hospital in Raleigh to return to duty. According to the card transcribed from the November–December 1864 unit muster rolls, Inman deserted from the hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina, and was dropped from the roll on November 2, 1864.

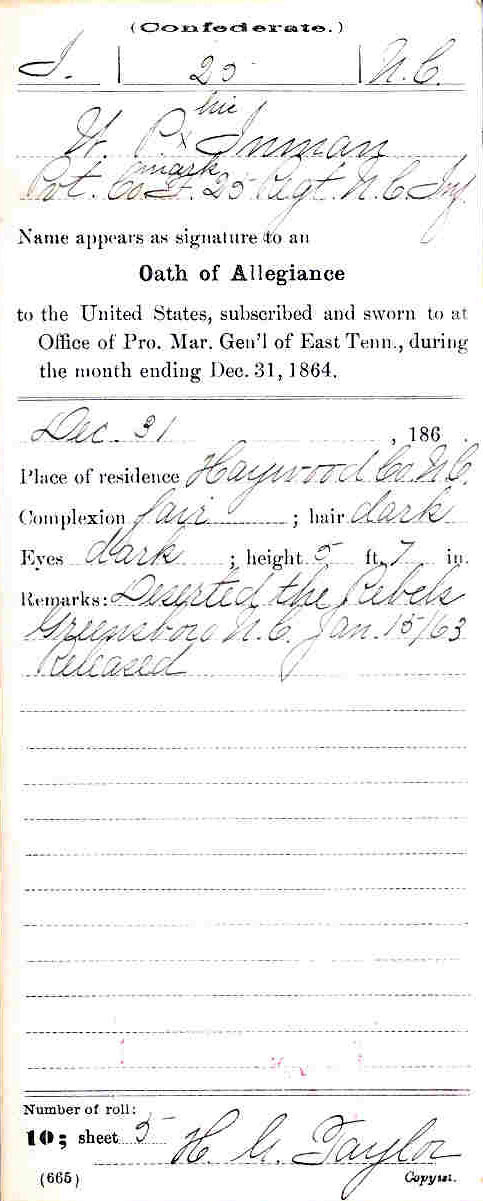

Finally, the last card in Inman's compiled military service record reveals that he signed an oath of allegiance to the United States during the month ending December 31, 1864, in East Tennessee. A note in the remarks section reveals that "[Inman] deserted the Rebels, Greensboro, North Carolina, January 15, 1863."

How can that be? According to the previous information in his compiled service record, he was present with his unit for all of 1863 and most of 1864. He was wounded at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, and his name appears as being present during that action. Why Inman gave this information to the Federal authorities cannot be fully known, for it contradicts information found in the unit muster rolls. Further clues might be revealed if the document related to the oath of allegiance could be located.

In very rare cases, additional information can be gleaned from related documents highlighted in the compiled military service record. Inman's service record card notes that he signed an oath of allegiance in the office of the Provost Marshal General of East Tennessee in December 1864, but the place where he swore the oath is not listed. A search through several series in Record Group 109 failed to turn up any listing for oaths of allegiance filed under "East Tennessee." The volumes in Entry 204 that record oaths of allegiance, however, reveal that Inman signed his oath in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the office of Brigadier General Carter. The provost marshal turns out to be Brig. Gen. Samuel Powhatan Carter, notable for being the only officer to attain the rank of major general in the U.S. Army and rear admiral in the U.S. Navy. Carter's cover letter to the War Department transmitting the list of "rebel deserters" who took the oath in his office in December 1864 is found in Record Group 249, Records of the Commissary General of Prisoners.

Now the search could return to Record Group 109, Entry 199, for records filed under Knoxville. There, on the original list of rebel deserters, is Inman's mark (the letter "X"). More intriguing, Inman is listed on the oath of allegiance list with an L. H. Inman who also served in Company F, Twenty-fifth North Carolina Infantry, and was from Haywood County, North Carolina. It turns out that L. H. Inman and W. P. Inman were brothers. Searching the federal population census schedules for Haywood County, North Carolina, we find the Inman brothers listed in the household of Joseph (Joshua) and Mary Inman in 1850.

In fact, all five of W. P. Inman's brothers served in the Civil War. Joshua and Lewis served alongside their brother William in Company F of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina. The other three, James, Daniel, and Joseph, served in Company I of the Sixty-second North Carolina.

According to his service record, Lewis H. Inman enrolled on the same day and in the same company as his brother William. Other facets of their wartime service also mirror each other. Both Inmans deserted their company on September 5, 1862, and returned to the unit on November 19. They were both pardoned for their offenses. Both privates later appear in Knoxville when they sign their oaths of allegiance. Could William Inman, whose lone journey home depicted in Cold Mountain, have been headed home with one of his brothers instead? Lewis survived the war, but according to family oral history, W. P. Inman was killed by Teague's Home Guard approximately three to four miles from his home. The records don't answer the question definitively but rather lead to more speculation and conjecture.

Many researchers come to the National Archives each year to explore Civil War records. Sometimes digging deeper into federal records can reveal answers to long-standing questions, make or break family tales, or uncover a story behind the story. Other times contradictions in family history or even other federal records are never resolved, such as the notation that Inman deserted in Greensboro in 1863 while other records show he was present with his unit at the time.

Civil War records at the National Archives go far beyond famous generals and battles. They can reveal more about a little-known private in the Confederate army whose descendant later wrote a best-selling book. Or they may shed light on one of your own ancestors who fought in the Civil War as an obscure private. Much as Inman trudged back to Cold Mountain facing trials and tribulations, researchers sometimes encounter unforeseen challenges as they follow the trail of records. But hopefully the researcher, unlike Inman, will find that the fun lies in the journey.

Richard W. Peuser is a supervisory archivist for the Old Military and Civil Records unit at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. He is a contributor to Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War (1996) and Naval Warfare: An International Encyclopedia (2002) and the author of "Documenting United States Naval Activities during the Spanish American War," Prologue (Spring 1998).

Trevor K. Plante is a reference archivist in the Old Military and Civil Records unit at the National Archives and Records Administration who specializes in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century military records. He is an active lecturer at the National Archives and a frequent contributor to Prologue.